Indigenous

Carney’s Throne Speech lacked moral leadership

This article supplied by Troy Media.

By Susan Korah

By Susan Korah

Carney’s throne speech offered pageantry, but ignored Indigenous treaty rights, MAID expansion and religious concerns

The Speech from the Throne, delivered by King Charles III on May 27 to open the latest session of Parliament under newly elected Prime Minister Mark Carney, was a confident assertion of Canada’s identity and outlined the government’s priorities for the session. However, beneath the

pageantry, it failed to address the country’s most urgent moral and constitutional responsibilities.

It also sent a coded message to U.S. President Donald Trump, subtly rebuking his repeated dismissal of Canada as a sovereign state. Trump has

previously downplayed Canada’s independence in trade talks and public statements, often treating it as economically subordinate to the U.S.

Still, a few discordant notes—most visibly from a group of First Nations chiefs in traditional headdresses—cut through the welcoming sounds that greeted the King and Queen Camilla on the streets of the capital.

The role of the Crown in Canada’s history sparked strong reactions from some Indigenous leaders who had travelled from as far as Alberta and Manitoba to voice their concerns.

“It’s time the Crown paid more than lip service to the Indigenous people of this country,” Chief Billy-Joe Tuccaro of the Mikisew Cree First Nation told me as he and his colleagues posed for photographs requested by several parade spectators. “We have been ignored and marginalized for far too long.”

He added that he and fellow chiefs from other First Nations were standing outside the Senate chamber as a symbol of their status as “outsiders,” despite being the land’s original inhabitants.

Shortly after Carney’s election, Tuccaro and Chief Sheldon Sunshine of the Sturgeon Lake Cree Nation sent him a joint letter stating: “As you

know, Canada is founded on Treaties that were sacred covenants between the Crown and our ancestors to share the lands. We are not prepared to accept any further Treaty breaches and violations.” They added that they looked forward to working with the new government as treaty partners.

Catholics, too, are being urged to remain vigilant about aspects of the government’s agenda that were either only briefly mentioned in the throne

speech or omitted altogether. On April 23, just days before Carney and the Liberals were returned to power, the Permanent Council of the Canadian Conference of Catholic Bishops issued a statement outlining what Catholics should expect from the new government.

“Our Catholic faith provides essential moral and social guidance, helping us understand and respond to the critical issues facing our country,” they wrote. “As the Church teaches, it is the duty of the faithful ‘to see that the divine law is inscribed in the life of the earthly city (Gaudium et Spes, n. 43.2).’”

The bishops expressed concern about the lack of legal protection for the unborn, the expansion of eligibility for medical assistance in dying (MAID)—which allows eligible Canadians to seek medically assisted death under specific legal conditions—and inadequate access to quality palliative care. They also reaffirmed the Church’s responsibility to walk “in justice and truth with Indigenous peoples.”

Although the speech emphasized tariffs, the removal of trade barriers and national security, it made no mention of the right to life, MAID or the charitable status of churches and church-related charities—a status the Trudeau government had considered revoking for some groups.

On Indigenous issues, the government pledged to be a reliable partner and to double the Indigenous Loan Guarantee Program from $5 billion to $10 billion. The program supports Indigenous equity participation in natural resource and infrastructure projects.

Canada deserves more than symbolic rhetoric—it needs a government that will confront its moral obligations head-on and act decisively on the challenges facing Indigenous peoples, faith communities, and the most vulnerable among us.

Susan Korah is Ottawa correspondent for The Catholic Register, a Troy Media Editorial Content Provider Partner.

Troy Media empowers Canadian community news outlets by providing independent, insightful analysis and commentary. Our mission is to support local media in helping Canadians stay informed and engaged by delivering reliable content that strengthens community connections and deepens understanding across the country.

Fraser Institute

Aboriginal rights now more constitutionally powerful than any Charter right

From the Fraser Institute

By Bruce Pardy

A judge of the British Columbia Supreme Court recently found that the Cowichan First Nation holds Aboriginal title over 800 acres of government land in Richmond, British Columbia. Wherever Aboriginal title is found to exist, said the court, it’s a “prior and senior right” to fee simple title, whether public or private. That means it trumps the property that Canadians hold in their houses, farms and factories.

In Canada, property rights do not have constitutional status. No right to property is included in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Fee simple title is merely a gloss on the state’s constitutional authority to tax, regulate and expropriate private property as it sees fit. But Aboriginal rights are different. They have become more constitutionally powerful than any Charter right.

In 1968, then-Justice Minister Pierre Trudeau released a consultation paper that proposed a constitutional charter of human rights. It was the first iteration of what would become the Charter. In the paper, Trudeau proposed to guarantee a right to property. So did drafts that followed. But some provincial governments were dead set against entrenching property rights. By 1980, property had been dropped from proposals. The final version of the Charter, adopted in 1982, does not mention it. Canada’s Constitution does not protect property rights.

Except for Aboriginal property. Trudeau’s 1968 paper made no mention of Aboriginal rights, nor did drafts leading up to the 1980 proposal. Aboriginal groups and their supporters launched a campaign to have Aboriginal rights recognized. They succeeded just in time. Section 35, essentially an afterthought, recognized and affirmed the “existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada.” That section was put into the Constitution but not as part of the Charter. That might sound like section 35 is weaker than a Charter right, but it’s the opposite.

Section 35 affirms Aboriginal rights that existed as of 1982. But since 1982, the Supreme Court of Canada has used section 35 to champion, enlarge and reimagine Aboriginal rights. The Court has “discovered” rights never recognized in the law before 1982. In 1997, it articulated a new vision of Aboriginal title. In 2004, it established the Crown’s “duty to consult.” In 2014, it recognized Aboriginal title over a tract of Crown land. In 2021, it gave Aboriginal rights under section 35 to an American Indigenous group.

Now the B.C. court in the Cowichan decision has said that Aboriginal title takes precedence over private property. Last November, a judge of the New Brunswick King’s Bench suggested similarly. Where a claim of Aboriginal title succeeds over land held in fee simple, she said, the court may instruct the government to expropriate the private property and hand it over to the Aboriginal group.

Governments and legislatures have shown little inclination to turn back these developments. But even if they wanted to, the Constitution stands in the way.

Section 33 of the Charter, the “Notwithstanding clause” (NWC), allows provincial legislatures and the federal Parliament to enact legislation notwithstanding the Charter rights guaranteed in sections 2 and 7 to 15. That means that they can pass statutes that might infringe these Charter rights. Use of the NWC clause prevents courts from striking down the statute as unconstitutional. The main part of the NWC reads:

33. (1) Parliament or the legislature of a province may expressly declare in an Act of Parliament or of the legislature, as the case may be, that the Act or a provision thereof shall operate notwithstanding a provision included in section 2 or sections 7 to 15 of this Charter.

Section 35 is not part of the Charter. It is not subject to the NWC. Legislatures cannot ignore it, legislate around it, or change its meaning. Barring a constitutional amendment, courts have exclusive domain over the scope and application of section 35. In the constitutional hierarchy, Aboriginal rights rest above the “fundamental freedoms” and rights of the Charter.

Lest there was any doubt about that status, section 25 of the Charter spells it out. Charter rights and freedoms, the section says, “shall not be construed so as to abrogate or derogate from any aboriginal, treaty or other rights or freedoms that pertain to the aboriginal peoples of Canada.”

That does not mean that Aboriginal rights are absolute. Legislation or government action may sometimes infringe Aboriginal rights. But courts, not legislatures, control when, where, and under what circumstances that can happen. The Supreme Court of Canada has established the process and criteria by which governments must justify infringements of section 35 to the courts’ satisfaction.

Section 35, like much of the rest of the Constitution, is subject to an onerous amending formula. It cannot be easily changed or repealed.

Business

The Truth Is Buried Under Sechelt’s Unproven Graves

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

Millions spent, no exhumations. What are we actually mourning?

From Aug. 15 to 17, 2025, the Canadian flag flew at half-mast above the British Columbia legislature. The stated reason: to honour the shíshálh Nation and mourn the alleged discovery of 81 unmarked graves of Indigenous children near the former St. Augustine’s Residential School in Sechelt.

But unlike genuine mourning, this display of grief lacked a body, a name or a single verifiable piece of evidence. As MLA Tara Armstrong rightly observed in her open letter to the Speaker, this symbolic act was “shameful”—a gesture unmoored from fact, driven by rumour, emotion and political inertia.

The flag was lowered in response to claims from University of Saskatchewan archaeologist Dr. Terry Clark. According to announcements from both 2023 and 2025, Dr. Clark “discovered” 81 unmarked graves using ground-penetrating radar—a tool that detects changes in soil, not bones. Its signals require interpretation—and in this case, the necessary context never arrived.

Even more concerning, there has been no release of names or records. Chief Lenora Joe of the shíshálh Nation said the names of the children are “well known” to Elders. Yet none have been made public: not a single missing child reported, no date of disappearance, no death certificate, not even a family willing to speak openly.

Instead, we’re being asked to accept deeply held recollections as conclusive proof—without corroborating evidence.

The original 40 anomalies—first announced in April 2023—appear to be located beneath the paved parking lot of the band’s administrative and cultural hub, the House of Hewhiwus complex. This land has been excavated before. At no point were any human remains discovered. As former Chief Warren Paull confirmed, “remains were never found” and the stories circulating then “don’t include burial at all.” The pattern of red dots in the band’s video—a tidy grid beneath the asphalt—looked less like sacred ground and more like a plumbing schematic.

The grief narrative, meanwhile, was presented with great care. Professionally produced videos showed solemn Elders, blurred radar images and mournful speeches—all designed to evoke emotion while discouraging inquiry. In one video, Chief Joe warned that asking questions would “cause trauma.”

But reconciliation doesn’t mean blind acceptance. Silencing questions isn’t healing—it risks turning reconciliation into a one-way narrative.

In a 2025 follow-up, Dr. Clark reported another 41 anomalies—this time likely in the community’s own cemetery on Sinku Drive. Brief footage confirms that GPR was conducted among existing gravesites, where decayed wooden markers would naturally result in “unmarked” burials. As Tara Armstrong noted, finding undocumented graves in or near a cemetery is about as surprising as spotting seagulls at a landfill.

Even so, political leaders continued to validate the narrative.

The B.C. government endorsed the claims with another round of symbolic mourning. In doing so, it lent the power of the state to what increasingly resembles collective fiction. Since 2021, similar claims across Canada have triggered government apologies, funding announcements and media headlines—often without physical evidence.

Residential schools were bureaucratic institutions. They kept meticulous enrolment and death logs. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission, with eight years of access to these archives, conducted more than 6,500 interviews and reviewed thousands of documents. It found no cases of children who disappeared without a trace. Despite this, $2.6 million in federal funds was spent in 2025 alone on the Sechelt investigation.

This isn’t reconciliation: it’s mythmaking dressed up as healing. Worse still, it undermines real tragedies by replacing verifiable history with folklore dressed up in government robes.

Governments should not promote unverified stories with ceremonial gestures. Flags lowered at half-mast should honour actual deaths, not narrative convenience. Public policy, especially around historical reckoning, must be rooted in fact, not feelings.

If reconciliation is to mean anything, it must be anchored in shared truth. And the truth is, we cannot mourn 81 phantom children because they almost certainly never existed.

Canadians must start insisting on evidence. The standard of proof should be no different here than in any serious allegation. The principle that underpins our justice system—innocent until proven guilty—must also guide our view of history.

State-sponsored guilt rituals disconnected from verifiable fact are not justice.

They are theatre.

And not even good theatre.

Marco Navarro-Genie is vice-president of research at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy and co-author, with Barry Cooper, of Canada’s COVID: The Story of a Pandemic Moral Panic (2023). With files from Nina Green.

-

Business2 days ago

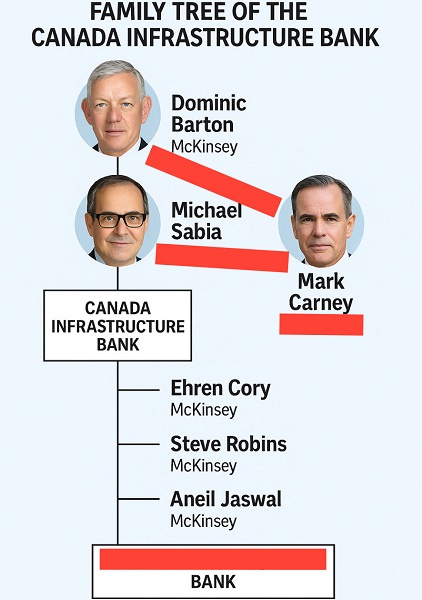

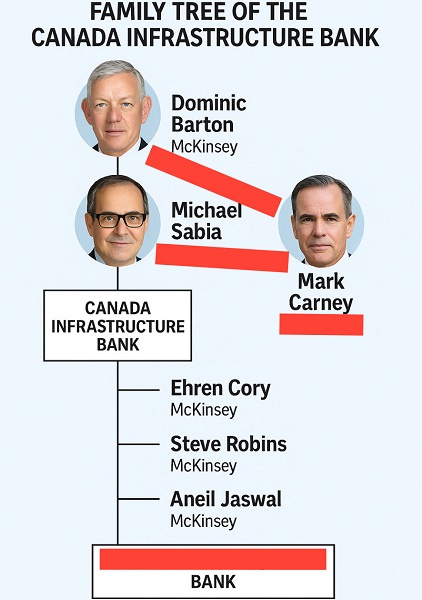

Business2 days agoDominic Barton’s Shadow Over $1-Billion PRC Ferry Deal: An Investigative Op-Ed

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoAlberta refuses to take part in Canadian government’s gun buyback program

-

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days ago

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days agoCanada To Revive Online Censorship Targeting “Harmful” Content, “Hate” Speech, and Deepfakes

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoOrthodox church burns to the ground in another suspected arson in Alberta

-

Fraser Institute1 day ago

Fraser Institute1 day agoAboriginal rights now more constitutionally powerful than any Charter right

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day ago$150 a week from the Province to help families with students 12 and under if teachers go on strike next week

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoNew PBO report underscores need for serious fiscal reform in Ottawa

-

Agriculture1 day ago

Agriculture1 day agoCarney’s nation-building plan forgets food