Business

Canadians are fed up with grocers maple‑washing their food

This article supplied by Troy Media.

Patriotic packaging on foreign food isn’t clever marketing—it’s maple‑washing, and it’s eroding trust

Canadian grocery retailers are misleading shoppers about where their food really comes from. Behind the patriotic packaging lies a growing problem: “maple‑washing”—using Canadian symbols to suggest products are homegrown when they’re not. It’s eroding consumer trust and must end.

That’s why more Canadians are paying closer attention to what labels actually mean. Awareness around origin labelling has grown as people learn the difference between “Product of Canada,” “Made in Canada,” and “Prepared in Canada.” The Food and Drugs Act requires labels to be truthful and not misleading. A “Product of Canada” must contain at least 98 per cent Canadian ingredients and processing. “Made in Canada” applies when the last substantial transformation happened here, while “Prepared in Canada” covers processing, packaging or handling in Canada regardless of ingredient source.

The differences may seem technical, but they matter. A frozen lasagna labelled “Prepared in Canada,” for example, could be made with imported pasta, sauce and meat—packaged here but not truly Canadian. These rules give consumers the clarity they need to make informed choices.

Armed with this clarity, many Canadians have become more selective about what they buy. That vigilance has emerged alongside a surge in consumer nationalism, spurred partly by geopolitical tensions and anti‑American sentiment. Even with U.S. giants like Walmart, Costco and Amazon dominating Canadian retail, many shoppers are deliberately avoiding American food products. The impact has been significant: NielsenIQ reports an 8.5 per cent drop in sales of American food products in Canada over just a few months. In an industry where sales usually shift by fractions of a per cent, such a drop is extraordinary. It shows how quickly Canadians are voting with their wallets.

That kind of shift, rare outside of crises, caught many grocers off guard. The sudden change left supply chains long dependent on U.S. products under pressure, and store‑level labelling grew inconsistent. Early missteps—like maple leaves displayed beside imported goods—were excused as logistical oversights. But six months later, those excuses no longer hold. Persisting with misleading displays and false origin claims has crossed the line into misrepresentation. Instances of oranges or almonds labelled as Canadian, with prices quietly adjusted after complaints, show the problem is systemic, not accidental.

Regulators have stepped in. The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) received 97 complaints about origin claims between November 2024 and mid‑July 2025. It investigated 91 cases and confirmed 29 violations. That level of scrutiny signals a growing intolerance for deceptive marketing.

The message to retailers is clear: this is not business as usual. Canadians have shown remarkable solidarity in supporting homegrown products during a time of economic strain and food insecurity. The least retailers can do is honour that trust by maintaining strict standards in labelling and merchandising. This is not about nationalism. It is about honesty. In today’s market, misleading customers is not only unethical but bad economics.

Consumers who suspect false origin claims should report them to the CFIA or to a retailer’s customer service. The CFIA generally investigates within 30 days. But the burden should not rest on shoppers to police grocery aisles. The responsibility lies with retailers to meet the moment with the same accountability they now expect from suppliers, regulators and consumers.

After months of consumer vigilance, it is up to grocers to end maple‑washing once and for all.

Dr. Sylvain Charlebois is a Canadian professor and researcher in food distribution and policy. He is senior director of the Agri-Food Analytics Lab at Dalhousie University and co-host of The Food Professor Podcast. He is frequently cited in the media for his insights on food prices, agricultural trends, and the global food supply chain.

Troy Media empowers Canadian community news outlets by providing independent, insightful analysis and commentary. Our mission is to support local media in helping Canadians stay informed and engaged by delivering reliable content that strengthens community connections and deepens understanding across the country.

Business

Your $350 Grocery Question: Gouging or Economics?

Dr. Sylvain Charlebois, a visiting scholar at McGill University and perhaps better known as the Food Professor, has lamented a strange and growing trend among Canadians. It seems that large numbers of especially younger people would prefer a world where grocery chains and food producers operated as non-profits and, ideally, were owned by governments.

Sure, some of them have probably heard stories about the empty shelves and rationing in Soviet-era food stores. But that’s just because “real” communism has never been tried.

In a slightly different context, University of Toronto Professor Joseph Heath recently responded to an adjacent (and popular) belief that there’s no reason we can’t grow all our food in publicly-owned farms right on our city streets and parks:

“Unfortunately, they do have answers, and anyone who stops to think for a minute will know what they are. It’s not difficult to calculate the amount of agricultural land that is required to support the population of a large urban area (such as Tokyo, where Saitō lives). All of the farms in Japan combined produce only enough food to sustain 38% of the Japanese population. This is all so obvious that it feels stupid even to be pointing it out.”

Sure, food prices have been rising. Here’s a screenshot from Statistics Canada’s Consumer Price Index price trends page. As you can see, the 12-month percentage change of the food component of the CPI is currently at 3.4 percent. That’s kind of inseparable from inflation.

But it’s just possible that there’s more going on here than greedy corporate price gouging.

It should be obvious that grocery retailers are subject to volatile supply chain costs. According to Statistics Canada, as of June 2025, for example, the price of “livestock and animal products” had increased by 130 percent over their 2007 prices. And “crops” saw a 67 percent increase over that same period. Grocers also have to lay out for higher packaging material costs that include an extra 35 percent (since 2021) for “foam products for packaging” and 78 percent more for “paperboard containers”.

In the years since 2012, farmers themselves had to deal with 49 percent growth in “commercial seed and plant” prices, 46 percent increases in the cost of production insurance, and a near-tripling of the cost of live cattle.

So should we conclude that Big Grocery is basically an industry whose profits are held to a barely sustainable minimum by macro economic events far beyond their control? Well that’s pretty much what the Retail Council of Canada (RCC) claims. Back in 2023, Competition Bureau Canada published a lengthy response from the RCC to the consultation on the Market study of retail grocery.

The piece made a compelling argument that food sales deliver razor-thin profit margins which are balanced by the sale of more lucrative non-food products like cosmetics.

However, things may not be quite as simple as the RCC presents them. For instance:

- While it’s true that the large number of supermarket chains in Canada suggests there’s little concentration in the sector, the fact is that most independents buy their stock as wholesale from the largest companies.

- The report pointed to Costco and Walmart as proof that new competitors can easily enter the market, but those decades-old well-financed expansions prove little about the way the modern market works. And online grocery shopping in Canada is still far from established.

- Consolidated reporting methods would make it hard to substantiate some of the report’s claims of ultra-thin profit margins on food.

- The fact that grocers are passing on costs selectively through promotional strategies, private-label pricing, and shrinkflation adjustments suggests that they retain at least some control over their supplier costs.

- The claim that Canada’s food price inflation is more or less the same as in other peer countries was true in 2022. But we’ve since seen higher inflation here than, for instance, in the U.S.

Nevertheless, there’s vanishingly little evidence to support claims of outright price gouging. Rising supply chain costs are real and even high-end estimates of Loblaw, Metro, and Sobeys net profit margins are in the two to five percent range. That’s hardly robber baron territory.

What probably is happening is some opportunistic margin-taking through various selective pricing strategies. And at least some price collusion has been confirmed.

How much might such measures have cost the average Canadian family? A reasonable estimate places the figure at between $150 and $350 a year. That’s real money, but it’s hardly enough to justify gutting the entire free market in favor of some suicidal system of central planning and control.

Business

The Grocery Greed Myth

Haultain’s Substack is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support our work, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Try it out.

The Justin Trudeau and Jagmeet Singh charges of “greedflation” collapses under scrutiny.

“It’s not okay that our biggest grocery stores are making record profits while Canadians are struggling to put food on the table.” —PM Justin Trudeau, September 13, 2023.

A couple of days after the above statement, the then-prime minister and his government continued a campaign to blame rising food prices on grocery retailers.

The line Justin Trudeau delivered in September 2023, triggered a week of political theatre. It also handed his innovation minister, François-Philippe Champagne, a ready-made role: defender of the common shopper against supposed corporate greed. The grocery price problem would be fixed by Thanksgiving that year. That was two years ago. Remember the promise?

But as Ian Madsen of the Frontier Centre for Public Policy has shown, the numbers tell a different story. Canada’s major grocers have not been posting “record profits.” They have been inching forward in a highly competitive, capital-intensive sector. Madsen’s analysis of industry profit margins shows this clearly.

Take Loblaw. Its EBITDA margin (earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation, and amortization) averaged 11.2 per cent over the three years ending 2024. That is up slightly from 10 per cent pre-COVID. Empire grew from 3.9 to 7.6 per cent. Metro went from 7.6 to 9.6. These are steady trends, not windfalls. As Madsen rightly points out, margins like these often reflect consolidation, automation, and long-term investment.

Meanwhile, inflation tells its own story. From March 2020 to March 2024, Canada’s money supply rose by 36 per cent. Consumer prices climbed about 20 per cent in the same window. That disparity suggests grocers helped absorb inflationary pressure rather than drive it. The Justin Trudeau and Jagmeet Singh charges of “greedflation” collapses under scrutiny.

Yet Ottawa pressed ahead with its chosen solution: the Grocery Code of Conduct. It was crafted in the wake of pandemic disruptions and billed as a tool for fairness. In practice, it is a voluntary framework with no enforcement and no teeth. The dispute resolution process will not function until 2026. Key terms remain undefined. Suppliers are told they can expect “reasonable substantiation” for sudden changes in demand. They are not told what that means. But food inflation remains.

This ambiguity helps no one. Large suppliers will continue to settle matters privately. Small ones, facing the threat of lost shelf space, may feel forced to absorb losses quietly. As Madsen observes, the Code is unlikely to change much for those it claims to protect.

What it does serve is a narrative. It lets the government appear responsive while avoiding accountability. It shifts attention away from the structural causes of price increases: central bank expansion, regulatory overload, and federal spending. Instead of owning the crisis, the state points to a scapegoat.

This method is not new. The Trudeau government, of which Carney’s is a continuation, has always shown a tendency to favour symbolism over substance. Its approach to identity politics follows the same pattern. Policies are announced with fanfare, dissent is painted as bigotry, and inconvenient facts are set aside.

The Grocery Code fits this model. It is not a policy grounded in need or economic logic. It is a ritual. It gives the illusion of action. It casts grocers as villains. It gives the impression to the uncaring public that the government is “providing solutions,” and that “it has their backs.” It flatters the state.

Madsen’s work cuts through that illusion. It reminds us that grocery margins are modest, inflation was monetary, and the public is being sold a story.

Canadians deserve better than fables, but they keep voting for the same folks. They don’t think to think that they deserve a government that governs within its limits; a government that accept its role in the crises it helped cause, and restores the conditions for genuine economic freedom. The Grocery Code is not a step in that direction. It was always a distraction, wrapped in a moral pose.

And like most moral poses in Ottawa, it leaves the facts behind.

Haultain’s Substack is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support our work, please consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Try it out.

-

National1 day ago

National1 day agoCanada’s birth rate plummets to an all-time low

-

Crime1 day ago

Crime1 day agoPierre Poilievre says Christians may be ‘number one’ target of hate violence in Canada

-

Opinion12 hours ago

Opinion12 hours agoJordan Peterson needs prayers as he battles serious health issues, daughter Mikhaila says

-

Censorship Industrial Complex13 hours ago

Censorship Industrial Complex13 hours agoWinnipeg Universities Flunk The Free Speech Test

-

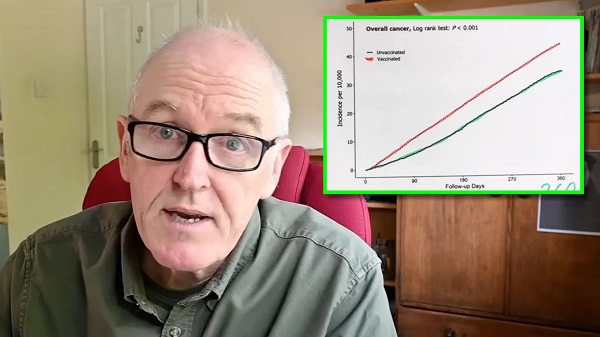

COVID-198 hours ago

COVID-198 hours agoDevastating COVID-19 Vaccine Side Effect Confirmed by New Data: Study

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoJason Kenney’s Separatist Panic Misses the Point

-

Automotive1 day ago

Automotive1 day agoBig Auto Wants Your Data. Trump and Congress Aren’t Having It.

-

Crime10 hours ago

Crime10 hours agoCanadian Sovereignty at Stake: Stunning Testimony at Security Hearing in Ottawa from Sam Cooper