Energy

Canada’s future prosperity runs through the northwest coast

From Resource Works

A strategic gateway to the world

Tucked into the north coast of B.C. is the deepest natural harbour in North America and the port with the shortest travel times to Asia.

With growing capacity for exports including agricultural products, lumber, plastic pellets, propane and butane, it’s no wonder the Port of Prince Rupert often comes up as a potential new global gateway for oil from Alberta, said CEO Shaun Stevenson.

Thanks to its location and natural advantages, the port can efficiently move a wide range of commodities, he said.

That could include oil, if not for the federal tanker ban in northern B.C.’s coastal waters.

“Notwithstanding the moratorium that was put in place, when you look at the attributes of the Port of Prince Rupert, there’s arguably no safer place in Canada to do it,” Stevenson said.

“I think that speaks to the need to build trust and confidence that it can be done safely, with protection of environmental risks. You can’t talk about the economic opportunity before you address safety and environmental protection.”

Safe transit at Prince Rupert

About a 16-hour drive from Vancouver, the Port of Prince Rupert’s terminals are one to two sailing days closer to Asia than other West Coast ports.

The entrance to the inner harbour is wider than the length of three Canadian football fields.

The water is 35 metres deep — about the height of a 10-storey building — compared to 22 metres at Los Angeles and 16 metres at Seattle.

Shipmasters spend two hours navigating into the port with local pilot guides, compared to four hours at Vancouver and eight at Seattle.

“We’ve got wide open, very simple shipping lanes. It’s not moving through complex navigational channels into the site,” Stevenson said.

A port on the rise

The Prince Rupert Port Authority says it has entered a new era of expansion, strengthening Canada’s economic security.

The port estimates it anchors about $60 billion of Canada’s annual global trade today. Even without adding oil exports, Stevenson said that figure could grow to $100 billion.

“We need better access to the huge and growing Asian market,” said Heather Exner-Pirot, director of energy, natural resources and environment at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.

“Prince Rupert seems purpose-built for that.”

Roughly $3 billion in new infrastructure is already taking shape, including the $750 million rail-to-container CANXPORT transloading complex for bulk commodities like specialty agricultural products, lumber and plastic pellets.

Canadian propane goes global

A centrepiece of new development is the $1.35-billion Ridley Energy Export Facility — the port’s third propane terminal since 2019.

“Prince Rupert is already emerging as a globally significant gateway for propane exports to Asia,” Exner-Pirot said.

Thanks to shipments from Prince Rupert, Canadian propane – primarily from Alberta – has gone global, no longer confined to U.S. markets.

More than 45 per cent of Canada’s propane exports now reach destinations outside the United States, according to the Canada Energy Regulator.

“Twenty-five per cent of Japan’s propane imports come through Prince Rupert, and just shy of 15 per cent of Korea’s imports. It’s created a lift on every barrel produced in Western Canada,” Stevenson said.

“When we look at natural gas liquids, propane and butane, we think there’s an opportunity for Canada via Prince Rupert becoming the trading benchmark for the Asia-Pacific region.”

That would give Canadian production an enduring competitive advantage when serving key markets in Asia, he said.

Deep connection to Alberta

The Port of Prince Rupert has been a key export hub for Alberta commodities for more than four decades.

Through the Alberta Heritage Savings Trust Fund, the province invested $134 million — roughly half the total cost — to build the Prince Rupert Grain Terminal, which opened in 1985.

The largest grain terminal on the West Coast, it primarily handles wheat, barley, and canola from the prairies.

Today, the connection to Alberta remains strong.

In 2022, $3.8 billion worth of Alberta exports — mainly propane, agricultural products and wood pulp — were shipped through the Port of Prince Rupert, according to the province’s Ministry of Transportation and Economic Corridors.

In 2024, Alberta awarded a $250,000 grant to the Prince Rupert Port Authority to lead discussions on expanding transportation links with the province’s Industrial Heartland region near Edmonton.

Handling some of the world’s biggest vessels

The Port of Prince Rupert could safely handle oil tankers, including Very Large Crude Carriers (VLCCs), Stevenson said.

“We would have the capacity both in water depth and access and egress to the port that could handle Aframax, Suezmax and even VLCCs,” he said.

“We don’t have terminal capacity to handle oil at this point, but there’s certainly terminal capacities within the port complex that could be either expanded or diversified in their capability.”

Market access lessons from TMX

Like propane, Canada’s oil exports have gained traction in Asia, thanks to the expanded Trans Mountain pipeline and the Westridge Marine Terminal near Vancouver — about 1,600 kilometres south of Prince Rupert, where there is no oil tanker ban.

The Trans Mountain expansion project included the largest expansion of ocean oil spill response in Canadian history, doubling capacity of the West Coast Marine Response Corporation.

The Canada Energy Regulator (CER) reports that Canadian oil exports to Asia more than tripled after the expanded pipeline and terminal went into service in May 2024.

As a result, the price for Canadian oil has gone up.

The gap between Western Canadian Select (WCS) and West Texas Intermediate (WTI) has narrowed to about $12 per barrel this year, compared to $19 per barrel in 2023, according to GLJ Petroleum Consultants.

Each additional dollar earned per barrel adds about $280 million in annual government royalties and tax revenues, according to economist Peter Tertzakian.

The road ahead

There are likely several potential sites for a new West Coast oil terminal, Stevenson said.

“A pipeline is going to find its way to tidewater based upon the safest and most efficient route,” he said.

“The terminal part is relatively straightforward, whether it’s in Prince Rupert or somewhere else.”

Under Canada’s Marine Act, the Port of Prince Rupert’s mandate is to enable trade, Stevenson said.

“If Canada’s trade objectives include moving oil off the West Coast, we’re here to enable it, presuming that the project has a mandate,” he said.

“If we see the basis of a project like this, we would ensure that it’s done to the best possible standard.”

This article originally appeared in Canadian Energy Centre

Resource Works News

Business

The world is no longer buying a transition to “something else” without defining what that is

From Resource Works

Even Bill Gates has shifted his stance, acknowledging that renewables alone can’t sustain a modern energy system — a reality still driving decisions in Canada.

You know the world has shifted when the New York Times, long a pulpit for hydrocarbon shame, starts publishing passages like this:

“Changes in policy matter, but the shift is also guided by the practical lessons that companies, governments and societies have learned about the difficulties in shifting from a world that runs on fossil fuels to something else.”

For years, the Times and much of the English-language press clung to a comfortable catechism: 100 per cent renewables were just around the corner, the end of hydrocarbons was preordained, and anyone who pointed to physics or economics was treated as some combination of backward, compromised or dangerous. But now the evidence has grown too big to ignore.

Across Europe, the retreat to energy realism is unmistakable. TotalEnergies is spending €5.1 billion on gas-fired plants in Britain, Italy, France, Ireland and the Netherlands because wind and solar can’t meet demand on their own. Shell is walking away from marquee offshore wind projects because the economics do not work. Italy and Greece are fast-tracking new gas development after years of prohibitions. Europe is rediscovering what modern economies require: firm, dispatchable power and secure domestic supply.

Meanwhile, Canada continues to tell itself a different story — and British Columbia most of all.

A new Fraser Institute study from Jock Finlayson and Karen Graham uses Statistics Canada’s own environmental goods and services and clean-tech accounts to quantify what Canada’s “clean economy” actually is, not what political speeches claim it could be.

The numbers are clear:

- The clean economy is 3.0–3.6 per cent of GDP.

- It accounts for about 2 per cent of employment.

- It has grown, but not faster than the economy overall.

- And its two largest components are hydroelectricity and waste management — mature legacy sectors, not shiny new clean-tech champions.

Despite $158 billion in federal “green” spending since 2014, Canada’s clean economy has not become the unstoppable engine of prosperity that policymakers have promised. Finlayson and Graham’s analysis casts serious doubt on the explosive-growth scenarios embraced by many politicians and commentators.

What’s striking is how mainstream this realism has become. Even Bill Gates, whose philanthropic footprint helped popularize much of the early clean-tech optimism, now says bluntly that the world had “no chance” of hitting its climate targets on the backs of renewables alone. His message is simple: the system is too big, the physics too hard, and the intermittency problem too unforgiving. Wind and solar will grow, but without firm power — nuclear, natural gas with carbon management, next-generation grid technologies — the transition collapses under its own weight. When the world’s most influential climate philanthropist says the story we’ve been sold isn’t technically possible, it should give policymakers pause.

And this is where the British Columbia story becomes astonishing.

It would be one thing if the result was dramatic reductions in emissions. The provincial government remains locked into the CleanBC architecture despite a record of consistently missed targets.

Since the staunchest defenders of CleanBC are not much bothered by the lack of meaningful GHG reductions, a reasonable person is left wondering whether there is some other motivation. Meanwhile, Victoria’s own numbers a couple of years ago projected an annual GDP hit of courtesy CleanBC of roughly $11 billion.

But here is the part that would make any objective analyst blink: when I recently flagged my interest in presenting my research to the CleanBC review panel, I discovered that the “reviewers” were, in fact, two of the key architects of the very program being reviewed. They were effectively asked to judge their own work.

You can imagine what they told us.

What I saw in that room was not an evidence-driven assessment of performance. It was a high-handed, fact-light defence of an ideological commitment. When we presented data showing that doctrinaire renewables-only thinking was failing both the economy and the environment, the reception was dismissive and incurious. It was the opposite of what a serious policy review looks like.

Meanwhile our hydro-based electricity system is facing historic challenges: long term droughts, soaring demand, unanswered questions about how growth will be powered especially in the crucial Northwest BC region, and continuing insistence that providers of reliable and relatively clean natural gas are to be frustrated at every turn.

Elsewhere, the price of change increasingly includes being able to explain how you were going to accomplish the things that you promise.

And yes — in some places it will take time for the tide of energy unreality to recede. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t be improving our systems, reducing emissions, and investing in technologies that genuinely work. It simply means we must stop pretending politics can overrule physics.

Europe has learned this lesson the hard way. Global energy companies are reorganizing around a 50-50 world of firm natural gas and renewables — the model many experts have been signalling for years. Even the New York Times now describes this shift with a note of astonishment.

British Columbia, meanwhile, remains committed to its own storyline even as the ground shifts beneath it. This isn’t about who wins the argument — it’s about government staying locked on its most basic duty: safeguarding the incomes and stability of the families who depend on a functioning energy system.

Resource Works News

Energy

Tanker ban politics leading to a reckoning for B.C.

From Resource Works

That a new oil pipeline from Alberta to BC is being aired by Ottawa and pushed by Alberta has, in turn, critics eagerly pushing carefully crafted scare stories.

Take the Green Party’s Elizabeth May, for one: She insists that oil tankers leaving Prince Rupert would be sailing through “Canada’s most dangerous waters and the fourth most dangerous waters in the world.”

First, this “dangerous waters” claim is unsubstantiated, unproven, and hyperbolic. It is apparently based on a line in a 1992 federal guide to marine-weather hazards on the west coast, but it is not credited or supported there.

Second, who says a new oil pipeline would go to Prince Rupert? No destination is specified in the memorandum of understanding published by Ottawa and Alberta.

It speaks of a commitment to “enable the export of bitumen from a strategic deep-water port to Asian markets.”

Energy Minister Tim Hodgson: “There is no route today. Under the MoU, what (Alberta) would need to do is work with the affected jurisdiction, British Columbia, and work with affected First Nations for that project to move forward. That’s what the work plan in the MoU calls for.”

First Nations concerned

Now, the MoU does say that this could include “if necessary” a change to the federal ban on oil tankers in northwest BC waters.

Some First Nations are strongly fighting the idea of oil tankers in northern BC waters citing fears of a catastrophic spill. The Assembly of First Nations (AFN), for example, is calling for the Canada-Alberta pipeline MoU to be scrapped.

“A pipeline to B.C.’s coast is nothing but a pipe dream,” said Chief Donald Edgars of Old Massett Village Council in Haida Gwaii.

And AFN National Chief Cindy Woodhouse Nepinak said: “Canada can create all the MOUs, project offices, advisory groups that they want: the chiefs are united. . . When it comes to approving large national projects on First Nations lands, there will not be getting around rights holders.”

Alberta group interested

But the Metis Settlements of Alberta say they’re interested in purchasing a stake in the proposed pipeline and want to “work with First Nations in British Columbia who oppose the project.”

The Alberta government’s Indigenous loan agency says a new oil pipeline to the BC coast could deliver “significant” returns for Indigenous Peoples.

Alberta Premier Danielle Smith has suggested the pipeline could bring in $2 billion a year in revenue, and that it could be as much as 50 per cent owned by Indigenous groups — who would thus earn $1 billion a year,

“Can you imagine the impact that would have on those communities in British Columbia and in Alberta? It’s extraordinary.”

And we note that in 2019 the First Nations-proposed Eagle Spirit Energy Corridor, which aimed to connect Alberta’s oilpatch to Kitimat, garnered serious interest among Indigenous groups. It had buy-in from 35 First Nations groups along the proposed corridor, with equity-sharing agreements floated with 400 others. (The project died with passage of the tanker ban.)

Vancouver more likely

More recent chatter, including remarks by BC Premier David Eby, would suggest oil from a new pipeline would more likely be through Vancouver, rather than via Prince Rupert or Kitimat BC. And tankers have been carrying oil from the Trans Mountain Pipeline System’s Burnaby terminal since 1956 — with no spills.

Oft cited by northern-port opponents is the major spill of 258,000 barrels of crude oil (more than 40 million litres) from the tanker Exxon Valdez, which ran aground in Alaska’s Prince William Sound in 1989.

The resulting spill killed native and marine wildlife over 2,100 km of coastline. The U.S. National Transportation Safety Board found that the spill occurred due to human error. It cited a tired third mate on watch, and noted the captain had an alcohol problem.

But the Exxon Valdez was a single-hull tanker. Its spill led to the phasing out of single-hull tankers, replaced in the ensuing 36 years by new generations of double-hull vessels (with an inner and outer hull separated to contain spills if the outer hull ruptures), new tanker safety rules — and new ways of dealing with the far-fewer spills.

Among those new ways is the Western Canada Marine Response Corporation: “Our mandate is to ensure there is a state of preparedness in place when a marine spill occurs and to mitigate the impacts on B.C.’s coast. This includes the protection of wildlife, economic and environmental sensitivities, and the safety of both responders and the public.”

What about LNG carriers?

At the same time, fear-mongers are actively flogging scare stories on social media.

One opposition group sees future LNG carrier traffic along the southern BC coast as potentially numbering “in the realm of 800+ transits a year.”

Eight hundred a year? BC Ferries runs more than 185,000 a year. And the ferries don’t have tethered tugs helping them to get safely from LNG terminals. And they don’t have BC Coast Pilots on the bridge to keep progress safe. Oil tankers leaving the Port of Vancouver have both.

As marine captain Duncan MacFarlane of LNG Canada in Kitimat says: “LNG carriers are some of the most sophisticated ships in the world…Once loading operations are complete (at LNG Canada), three BC Pilots will join the ship and start navigating up the Douglas Channel, which is approximately 159 nautical miles out to the Prince Rupert pilot station.”

“LNG Canada has partnered with HaiSea Marine, which is a company formed between the Haisla Nation and Vancouver-based SeaSpan, to provide two escort tugs and three harbour-assist tugs to safely move the vessel out of the Douglas Channel…once the vessel drops the pilots at Prince Rupert, it starts a seven- to ten-day voyage to its discharge port. To assist with this, they’ll use satellite navigation, weather routing, and a variety of other technologies to get to their port the safest and most efficient way.”

The same would apply to oil tankers from any northern port in BC.

BC’s tanker-safety record

As the small-c conservative Fraser Institute points out: “Pipelines are 2.5 times safer than rail for oil transportation, and oil tankers have [the] safest record of all.”

And it adds: “The history of oil transport off of Canada’s coasts is one of incredible safety, whether of Canadian or foreign origin, long predating federal Bill C-48’s tanker ban. . . .new pipelines and additional transport of oil from (and along) B.C. coastal waters is likely very low environmental risk. In the meantime, a regular stream of oil tankers and large fuel-capacity ships have been cruising up and down the B.C. coast between Alaska and U.S. west coast ports for decades with great safety records.”

This last refers to the 200-230 tankers a year that now carry crude oil from Alaska through Canadian waters south of Haida Gwaii and then down BC’s Inside Passage or outer coastal waters to Juan de Fuca Strait and Washington refineries.

While these tankers do not transit Hecate Strait (the north end of which is the area of concern about spills from tankers from Prince Rupert or Kitimat) all these US tankers are double-hulled, must report positions, speeds and routes in real-time, must carry certified pilots, must use traffic-separation routes (like traffic lanes), and must slow to 11 knots in sensitive areas.

And as Pipeline Action says: “Canada is not inferior — If Norway can move tankers safely through fjords, if Japan can operate in some of the busiest waterways on Earth, if Alaska balances ecological protection with responsible shipping and if Eastern Canadian ports manage tankers every day, then Canada’s West Coast, with its governance standards, technical capacity and Indigenous partnership potential, can certainly do so.”

Resource Works News

-

Business2 days ago

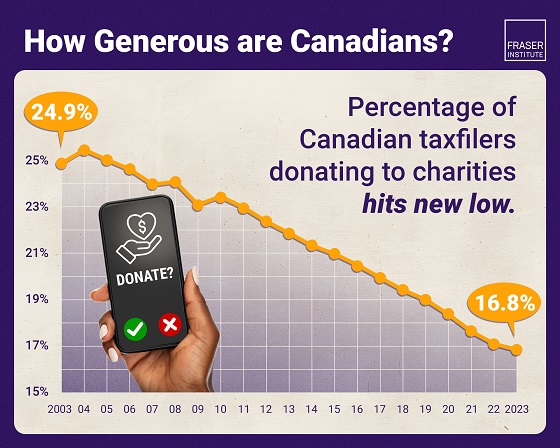

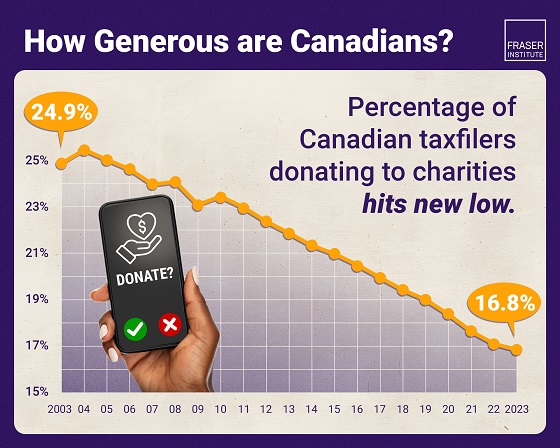

Business2 days agoAlbertans give most on average but Canadian generosity hits lowest point in 20 years

-

Bruce Dowbiggin1 day ago

Bruce Dowbiggin1 day agoCarney Hears A Who: Here Comes The Grinch

-

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days ago

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days agoOttawa’s New Hate Law Goes Too Far

-

National1 day ago

National1 day agoCanada’s free speech record is cracking under pressure

-

Fraser Institute1 day ago

Fraser Institute1 day agoClaims about ‘unmarked graves’ don’t withstand scrutiny

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoTaxpayers Federation calls on politicians to reject funding for new Ottawa Senators arena

-

Digital ID1 day ago

Digital ID1 day agoCanada considers creating national ID system using digital passports for domestic use

-

Energy1 day ago

Energy1 day agoMeet REEF — the massive new export engine Canadians have never heard of