Business

Canada’s economy teeming with troubling stats

From the Fraser Institute

It’s striking that Canada has around 100,000 fewer entrepreneurs than two decades ago, even though the population has increased dramatically over that time.

Earlier this week, we marked another Labour Day, and Canada’s job market is losing steam. The slowdown is occurring against the backdrop of unprecedented tariff hikes, persistent geopolitical tensions, and a stagnant Canadian economy. Nationally, employment fell by 40,000 between June and July, with the job losses concentrated in fulltime private-sector positions. Total employment in July was scarcely higher than it was in January (measured on a seasonally adjusted basis). Manufacturing and construction are among the industries that have posted sizable job declines so far in 2025.

The picture is less gloomy on a year-over-year basis. Employment in Canada rose by 1.5 per cent from July 2024 to July 2025. But the month-to-month pace of job creation has been decelerating. Meanwhile, the unemployment rate has been ticking higher. In July, Canada-wide unemployment stood at 6.9 per cent, up from 5.7 per cent 18 months ago. Job vacancy rates have also been falling. Young adults are bearing much of the burden of Canada’s slumping labour market. Oddly, even amid a recession-bound economy, the federal government inexplicably continues to admit large numbers of temporary foreign workers.

Digging deeper into the data—and going back further to the pre-COVID years—yields insight into the dynamics of Canadian job creation. Looking at the period from January 2019 to July 2025 (roughly six-and-a-half years), we can track the trends in three broad employment categories: private-sector payroll jobs, public-sector jobs and the self-employed.

Since the start of 2019, public-sector jobs are up by almost one-quarter, while private-sector payroll positions have increased by 10 per cent. Meanwhile, the number of self-employed Canadians declined over the same period, suggesting a deterioration of the climate for entrepreneurship in the country. That’s troubling.

Entrepreneurs and startup businesses are the lifeblood of a dynamic market economy. Indeed, economists recognize that a key marker of a thriving economy is a healthy rate of business formation. New businesses are an important source of innovation and fresh ideas. They also help to inject competitive vigour into both local markets and the wider economy—something that’s clearly necessary in Canada, given years of subdued business growth and the cartelization of large swathes of our economy. Accelerating business formation should be a top priority for governments at all levels. Supporting the commercial success of existing young firms is also crucial, given the outsized contributions they make to the overall economic growth process.

For entrepreneurs and others who invest in startup companies, the risk of failure is ever present. Many new businesses don’t survive. In the goods-producing sector of the Canadian economy, about 70 per cent of new businesses survive for at least five years; in the broad services-producing sector, the rate is lower (56 per cent). Ten-year survival rates are around 50 per cent in goods-producing industries and just 35 per cent in service-based industries. Becoming a businessowner/operator is not for the faint of heart.

Canada urgently needs more high-growth businesses. This means building a robust pipeline of new entrepreneurial ventures.

Unfortunately, we have been falling short in this area, with the rate of business startups diminishing. It’s striking that Canada has around 100,000 fewer entrepreneurs than two decades ago, even though the population has increased dramatically over that time.

Canadian policymakers would be wise to ask themselves why entrepreneurship is faltering. Governments should act to modify their tax, regulatory and industrial policies to establish an economic environment that’s more conducive to entrepreneurial wealth-creation and the growth of small and medium-sized businesses.

Business

Fuelled by federalism—America’s economically freest states come out on top

From the Fraser Institute

Do economic rivalries between Texas and California or New York and Florida feel like yet another sign that America has become hopelessly divided? There’s a bright side to their disagreements, and a new ranking of economic freedom across the states helps explain why.

As a popular bumper sticker among economists proclaims: “I heart federalism (for the natural experiments).” In a federal system, states have wide latitude to set priorities and to choose their own strategies to achieve them. It’s messy, but informative.

New York and California, along with other states like New Mexico, have long pursued a government-centric approach to economic policy. They tax a lot. They spend a lot. Their governments employ a large fraction of the workforce and set a high minimum wage.

They aren’t socialist by any means; most property is still in private hands. Consumers, workers and businesses still make most of their own decisions. But these states control more resources than other states do through taxes and regulation, so their governments play a larger role in economic life.

At the other end of the spectrum, New Hampshire, Tennessee, Florida and South Dakota allow citizens to make more of their own economic choices, keep more of their own money, and set more of their own terms of trade and work.

They aren’t free-market utopias; they impose plenty of regulatory burdens. But they are economically freer than other states.

These two groups have, in other words, been experimenting with different approaches to economic policy. Does one approach lead to higher incomes or faster growth? Greater economic equality or more upward mobility? What about other aspects of a good society like tolerance, generosity, or life satisfaction?

For two decades now, we’ve had a handy tool to assess these questions: The Fraser Institute’s annual “Economic Freedom of North America” index uses 10 variables in three broad areas—government spending, taxation, and labor regulation—to assess the degree of economic freedom in each of the 50 states and the territory of Puerto Rico, as well as in Canadian provinces and Mexican states.

It’s an objective measurement that allows economists to take stock of federalism’s natural experiments. Independent scholars have done just that, having now conducted over 250 studies using the index. With careful statistical analyses that control for the important differences among states—possibly confounding factors such as geography, climate, and historical development—the vast majority of these studies associate greater economic freedom with greater prosperity.

In fact, freedom’s payoffs are astounding.

States with high and increasing levels of economic freedom tend to see higher incomes, more entrepreneurial activity and more net in-migration. Their people tend to experience greater income mobility, and more income growth at both the top and bottom of the income distribution. They have less poverty, less homelessness and lower levels of food insecurity. People there even seem to be more philanthropic, more tolerant and more satisfied with their lives.

New Hampshire, Tennessee, and South Dakota topped the latest edition of the report while Puerto Rico, New Mexico, and New York rounded out the bottom. New Mexico displaced New York as the least economically free state in the union for the first time in 20 years, but it had always been near the bottom.

The bigger stories are the major movers. The last 10 years’ worth of available data show South Carolina, Ohio, Wisconsin, Idaho, Iowa and Utah moving up at least 10 places. Arizona, Virginia, Nebraska, and Maryland have all slid down 10 spots.

Over that same decade, those states that were among the freest 25 per cent on average saw their populations grow nearly 18 times faster than those in the bottom 25 per cent. Statewide personal income grew nine times as fast.

Economic freedom isn’t a panacea. Nor is it the only thing that matters. Geography, culture, and even luck can influence a state’s prosperity. But while policymakers can’t move mountains or rewrite cultures, they can look at the data, heed the lessons of our federalist experiment, and permit their citizens more economic freedom.

Automotive

Politicians should be honest about environmental pros and cons of electric vehicles

From the Fraser Institute

By Annika Segelhorst and Elmira Aliakbari

According to Steven Guilbeault, former environment minister under Justin Trudeau and former member of Prime Minister Carney’s cabinet, “Switching to an electric vehicle is one of the most impactful things Canadians can do to help fight climate change.”

And the Carney government has only paused Trudeau’s electric vehicle (EV) sales mandate to conduct a “review” of the policy, despite industry pressure to scrap the policy altogether.

So clearly, according to policymakers in Ottawa, EVs are essentially “zero emission” and thus good for environment.

But is that true?

Clearly, EVs have some environmental advantages over traditional gasoline-powered vehicles. Unlike cars with engines that directly burn fossil fuels, EVs do not produce tailpipe emissions of pollutants such as nitrogen dioxide and carbon monoxide, and do not release greenhouse gases (GHGs) such as carbon dioxide. These benefits are real. But when you consider the entire lifecycle of an EV, the picture becomes much more complicated.

Unlike traditional gasoline-powered vehicles, battery-powered EVs and plug-in hybrids generate most of their GHG emissions before the vehicles roll off the assembly line. Compared with conventional gas-powered cars, EVs typically require more fossil fuel energy to manufacture, largely because to produce EVs batteries, producers require a variety of mined materials including cobalt, graphite, lithium, manganese and nickel, which all take lots of energy to extract and process. Once these raw materials are mined, processed and transported across often vast distances to manufacturing sites, they must be assembled into battery packs. Consequently, the manufacturing process of an EV—from the initial mining of materials to final assembly—produces twice the quantity of GHGs (on average) as the manufacturing process for a comparable gas-powered car.

Once an EV is on the road, its carbon footprint depends on how the electricity used to charge its battery is generated. According to a report from the Canada Energy Regulator (the federal agency responsible for overseeing oil, gas and electric utilities), in British Columbia, Manitoba, Quebec and Ontario, electricity is largely produced from low- or even zero-carbon sources such as hydro, so EVs in these provinces have a low level of “indirect” emissions.

However, in other provinces—particularly Alberta, Saskatchewan and Nova Scotia—electricity generation is more heavily reliant on fossil fuels such as coal and natural gas, so EVs produce much higher indirect emissions. And according to research from the University of Toronto, in coal-dependent U.S. states such as West Virginia, an EV can emit about 6 per cent more GHG emissions over its entire lifetime—from initial mining, manufacturing and charging to eventual disposal—than a gas-powered vehicle of the same size. This means that in regions with especially coal-dependent energy grids, EVs could impose more climate costs than benefits. Put simply, for an EV to help meaningfully reduce emissions while on the road, its electricity must come from low-carbon electricity sources—something that does not happen in certain areas of Canada and the United States.

Finally, even after an EV is off the road, it continues to produce emissions, mainly because of the battery. EV batteries contain components that are energy-intensive to extract but also notoriously challenging to recycle. While EV battery recycling technologies are still emerging, approximately 5 per cent of lithium-ion batteries, which are commonly used in EVs, are actually recycled worldwide. This means that most new EVs feature batteries with no recycled components—further weakening the environmental benefit of EVs.

So what’s the final analysis? The technology continues to evolve and therefore the calculations will continue to change. But right now, while electric vehicles clearly help reduce tailpipe emissions, they’re not necessarily “zero emission” vehicles. And after you consider the full lifecycle—manufacturing, charging, scrapping—a more accurate picture of their environmental impact comes into view.

-

Bruce Dowbiggin24 hours ago

Bruce Dowbiggin24 hours agoWayne Gretzky’s Terrible, Awful Week.. And Soccer/ Football.

-

espionage13 hours ago

espionage13 hours agoWestern Campuses Help Build China’s Digital Dragnet With U.S. Tax Funds, Study Warns

-

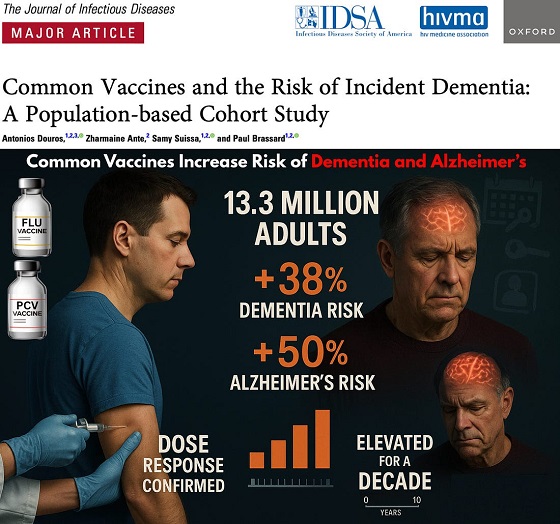

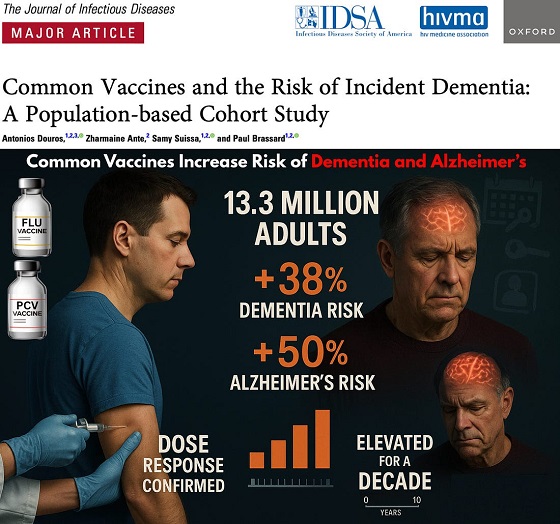

Focal Points4 hours ago

Focal Points4 hours agoCommon Vaccines Linked to 38-50% Increased Risk of Dementia and Alzheimer’s

-

Opinion22 hours ago

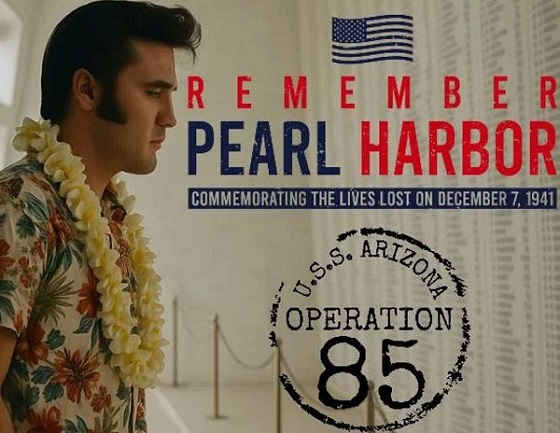

Opinion22 hours agoThe day the ‘King of rock ‘n’ roll saved the Arizona memorial

-

Agriculture23 hours ago

Agriculture23 hours agoCanada’s air quality among the best in the world

-

Business11 hours ago

Business11 hours agoCanada invests $34 million in Chinese drones now considered to be ‘high security risks’

-

Health2 hours ago

Health2 hours agoThe Data That Doesn’t Exist

-

Economy12 hours ago

Economy12 hours agoAffordable housing out of reach everywhere in Canada