Addictions

Calls for Public Inquiry Into BC Health Ministry Opioid Dealing Corruption

The leaked audit shows from 2022 to 2024, a staggering 22,418,000 doses of opioids were prescribed by doctors and pharmacists to approximately 5,000 clients in B.C., including fentanyl patches.

A confidential investigation by British Columbia’s Ministry of Health, Financial Operations and Audit Branch has uncovered explosive allegations of fraud, abuse, and organized crime infiltration within PharmaCare’s prescribed opioid alternatives program. Internal audit findings, obtained by The Bureau, suggest that millions of taxpayer dollars are being diverted into illicit drug trafficking networks rather than serving harm reduction efforts.

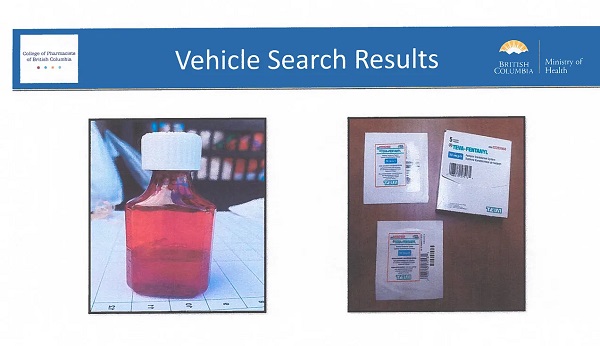

The leaked documents include photographs from vehicle searches that show collections of fentanyl patches and Dilaudid (hydromorphone) apparently packaged for resale after being stolen from the taxpayer-funded “safer supply” program. This program expanded dramatically following a federal law change implemented by Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government in 2020, which broadened circumstances in which pharmacy staff could dispense opioids, according to the document’s evidence.

“Prior to March 17, 2020, only pharmacists in BC were permitted to deliver [addiction therapy treatment] drugs,” the audit says.

B.C.’s safer supply program was launched in March 2020 as a response to the opioid overdose crisis, declared in 2016. It allows people with opioid-use disorder to receive prescribed drugs to be used on-site or taken away for later use.

The Special Investigations Unit and PharmaCare Audit Intelligence team identified a disturbing link between doctors, pharmacists, assisted living residences, and organized crime, where prescription opioids meant to replace illicit drugs are instead being diverted, sold, and trafficked at scale.

“A significant portion of the opioids being freely prescribed by doctors and pharmacists are not being consumed by their intended recipients,” the document states.

It suggests that financial incentives have created a business model for organized crime, asserting that “prescribed alternatives (safe supply opioids) are trafficked provincially, nationally, and internationally,” and that “proceeds of fraud” are being used to pay incentives to doctors, pharmacists, and intermediaries.

BC Conservative critic Elenore Sturko, a former RCMP officer, began raising concerns about the program two years ago after hearing anecdotes about prescribed opioids being trafficked. She asserts that the program is a failure in public policy and insists that Provincial Health Officer Dr. Bonnie Henry be dismissed for having “denied and downplayed” problems as they emerged. Sturko also argues that B.C. must change its drug policy in light of U.S. President Donald Trump’s stance linking the trafficking of fentanyl and other opioids to potential trade sanctions against Canada.

The document shows that PharmaCare’s dispensing fee loophole has incentivized pharmacies to maximize billings per patient, with some locations charging up to $11,000 per patient per year—compared to just $120 in normal cases.

Perhaps most alarming is the deep infiltration of B.C.’s safer supply program by criminal networks. The Ministry of Health report lists “Gang Members/Organized Crime” as key players in the prescription drug pipeline, which includes “Doctors, pharmacies, and assisted living residences.”

This revelation confirms long-standing fears that B.C.’s “safe supply” policy—originally designed to prevent deaths from contaminated street drugs—is instead sometimes supplying criminal organizations with pharmaceutical-grade opioids.

The leaked audit shows from 2022 to 2024, a staggering 22,418,000 doses of opioids were prescribed by doctors and pharmacists to approximately 5,000 clients in B.C., including fentanyl patches.

Beyond organized crime’s direct involvement, pharmacies themselves have exploited regulatory gaps to generate massive profits from PharmaCare’s policies:

- Pharmacies offer kickbacks to doctors, housing staff, and medical professionals to steer patients toward specific locations.

- Financial incentives fuel fraud, with multiple investigations identifying 60+ pharmacies offering incentives to clients.

- Non-health professionals, including housing staff, are witnessing OAT (opioid agonist treatment) dosing, violating patient safety protocols.

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

For the full experience, please upgrade your subscription and support a public interest startup. We break international stories and this requires elite expertise, time and legal costs.

Addictions

Canadian gov’t not stopping drug injection sites from being set up near schools, daycares

From LifeSiteNews

Canada’s health department told MPs there is not a minimum distance requirement between safe consumption sites and schools, daycares or playgrounds.

So-called “safe” drug injection sites do not require a minimum distance from schools, daycares, or even playgrounds, Health Canada has stated, and that has puzzled some MPs.

Canadian Health Minister Marjorie Michel recently told MPs that it was not up to the federal government to make rules around where drug use sites could be located.

“Health Canada does not set a minimum distance requirement between safe consumption sites and nearby locations such as schools, daycares or playgrounds,” the health department wrote in a submission to the House of Commons health committee.

“Nor does the department collect or maintain a comprehensive list of addresses for these facilities in Canada.”

Records show that there are 31 such “safe” injection sites allowed under the Controlled Drugs And Substances Act in six Canadian provinces. There are 13 are in Ontario, five each in Alberta, Quebec, and British Columbia, and two in Saskatchewan and one in Nova Scotia.

The department noted, as per Blacklock’s Reporter, that it considers the location of each site before approving it, including “expressions of community support or opposition.”

Michel had earlier told the committee that it was not her job to decide where such sites are located, saying, “This does not fall directly under my responsibility.”

Conservative MP Dan Mazier had asked for limits on where such “safe” injection drug sites would be placed, asking Michel in a recent committee meeting, “Do you personally review the applications before they’re approved?”

Michel said that “(a)pplications are reviewed by the department.”

Mazier stated, “Are you aware your department is approving supervised consumption sites next to daycares, schools and playgrounds?”

Michel said, “Supervised consumption sites were created to prevent overdose deaths.”

Mazier continued to press Michel, asking her how many “supervised consumption sites approved by your department are next to daycares.”

“I couldn’t tell you exactly how many,” Michel replied.

Mazier was mum on whether or not her department would commit to not approving such sites near schools, playgrounds, or daycares.

An injection site in Montreal, which opened in 2024, is located close to a kindergarten playground.

Conservative Party leader Pierre Poilievre has called such sites “drug dens” and has blasted them as not being “safe” and “disasters.”

Records show that the Liberal government has spent approximately $820 million from 2017 to 2022 on its Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy. However, even Canada’s own Department of Health admitted in a 2023 report that the Liberals’ drug program only had “minimal” results.

Recently, LifeSiteNews reported that the British Columbia government decided to stop a so-called “safe supply” free drug program in light of a report revealing many of the hard drugs distributed via pharmacies were resold on the black market.

British Columbia Premier David Eby recently admitted that allowing the decriminalization of hard drugs in British Columbia via a federal pilot program was a mistake.

Former Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s loose drug initiatives were deemed such a disaster in British Columbia that Eby’s government asked Trudeau to re-criminalize narcotic use in public spaces, a request that was granted.

Official figures show that overdoses went up during the decriminalization trial, with 3,313 deaths over 15 months, compared with 2,843 in the same time frame before drugs were temporarily legalized.

Addictions

Canada is divided on the drug crisis—so are its doctors

When it comes to addressing the national overdose crisis, the Canadian public seems ideologically split: some groups prioritize recovery and abstinence, while others lean heavily into “harm reduction” and destigmatization. In most cases, we would defer to the experts—but they are similarly divided here.

This factionalism was evident at the Canadian Society of Addiction Medicine’s (CSAM) annual scientific conference this year, which is the country’s largest gathering of addiction medicine practitioners (e.g., physicians, nurses, psychiatrists). Throughout the event, speakers alluded to the field’s disunity and the need to bridge political gaps through collaborative, not adversarial, dialogue.

This was a major shift from previous conferences, which largely ignored the long-brewing battles among addiction experts, and reflected a wider societal rethink of the harm reduction movement, which was politically hegemonic until very recently.

Recovery-oriented care versus harm reductionism

For decades, most Canadian addiction experts focused on shepherding patients towards recovery and encouraging drug abstinence. However, in the 2000s, this began to shift with the rise of harm reductionism, which took a more tolerant view of drug use.

On the surface, harm reductionists advocated for pragmatically minimizing the negative consequences of risky use—for example, through needle exchanges and supervised consumption sites. Additionally, though, many of them also claimed that drug consumption is not inherently wrong or shameful, and that associated harms are primarily caused not by drugs themselves but by the stigmatization and criminalization of their use. In their view, if all hard drugs were legalized and destigmatized, then they would eventually become as banal as alcohol and tobacco.

The harm reductionists gained significant traction in the 2010s thanks to the popularization of street fentanyl. The drug’s incredible potency caused an explosion of deaths and left users with formidable opioid tolerances that rendered traditional addiction medications, such as methadone, less effective. Amid this crisis, policymakers embraced harm reduction out of an immediate need to make drug use slightly less lethal. This typically meant supervising consumption, providing sterile drug paraphernalia, and offering “cleaner” substances for addicts to use.

Many abstinence-oriented addiction experts supported some aspects of harm reduction. They valued interventions that could demonstrably save lives without significant tradeoffs, and saw them as both transitional and as part of a larger public health toolkit. Distributing clean needles and Naloxone, an overdose-reversal medication, proved particularly popular. “People can’t recover if they’re dead,” went a popular mantra from the time.

Saving lives or enabling addiction?

However, many of these addiction experts were also uncomfortable with the broader political ideologies animating the movement and did not believe that drug use should be normalized. Many felt that some experimental harm reduction interventions in Canada were either conceptually flawed or that their implementation had deviated from what had originally been promised.

Some argued, not unreasonably, that the country’s supervised consumption sites are being mismanaged and failing to connect vulnerable addicts to recovery-oriented care. Most of their ire, however, was directed at “safer supply”—a novel strategy wherein addicts are given free drugs, predominantly hydromorphone (a heroin-strength opioid), without any real supervision.

While safer supply was meant to dissuade recipients from using riskier street drugs, addiction physicians widely reported that patients were selling their free hydromorphone to buy stronger illicit fentanyl, thereby flooding communities with diverted opioids and exacerbating the addiction crisis. They also noted that the “evidence base” behind safer supply was exceptionally poor and would not meet normal health-care standards.

Yet, critics of safer supply, and harm reduction radicalism more broadly, were often afraid to voice their opinions. The harm reductionists were institutionally and culturally dominant in the late 2010s and early 2020s, and opponents often faced activist harassment, aggressive gaslighting, and professional marginalization. A culture of self-censorship formed, giving both the public and influential policymakers a false impression of scientific consensus where none actually existed.

The resurgence in recovery-oriented strategies

Things changed in the mid-2020s. British Columbia’s failed drug decriminalization experiment eroded public trust in harm reductionism, and the scandalous failures of safer supply—and supervised consumption sites, too—were widely publicized in the national media.1

Whereas harm reductionism was once so powerful that opponents were dismissed as anti-scientific, there is now a resurgent interest in alternative, recovery-oriented strategies.

These cultural shifts have fuelled a more fractious, but intellectually honest, national debate about how to tackle the overdose crisis. This has ruptured the institutional dominance enjoyed by harm reductionists in the addiction medicine world and allowed their previously silenced opponents to speak up.

When I first attended CSAM’s annual scientific conference two years ago, recovery-oriented critics of radical harm reductionism were not given any platforms, with the exception of one minor presentation on safer supply diversion. Their beliefs seemed clandestine and iconoclastic, despite seemingly having wide buy-in from the addiction medicine community.

While vigorous criticism of harm reductionism was not a major feature of this year’s conference, there was open recognition that legitimate opposition to the movement existed. One major presentation, given by Dr. Didier Jutras-Aswad, explicitly cited safer supply and involuntary treatment as two foci of contention, and encouraged harm reductionists and recovery-oriented experts to grab coffee with one another so that they might foster some sense of mutual understanding.2

Is this change enough?

While CSAM should be commended for encouraging cross-ideological dialogue, its efforts, in this respect, were also superficial and vague. They chose to play it safe, and much was left unsaid and unexplored.

Two addiction medicine doctors I spoke with at the conference—both of whom were critics of safer supply and asked for anonymity—were nonplussed. “You can feel the tension in the air,” said one, who likened the conference to an awkward family dinner where everyone has tacitly agreed to ignore a recent feud. “Reconciliation requires truth,” said the other.

One could also argue that the organization has taken an inconsistent approach to encouraging respectful dialogue. When recovery-oriented experts were being bullied for their views a few years ago, they were largely left on their own. Now that their side is ascendant, and harm reductionists are politically vulnerable, mutual respect is in fashion again.

When I asked to interview the organization about navigating dissension, they sent a short, unspecific statement that emphasized “evidence-based practices” and the “benefits of exploring a variety of viewpoints, and the need to constantly challenge or re-evaluate our own positions based on the available science.”

But one cannot simply appeal to “evidence-based practices” when research is contentious and vulnerable to ideological meddling or misrepresentation.

Compared to other medical disciplines, addiction medicine is highly political. Grappling with larger, non-empirical questions about the role of drug use in society has always necessitated taking a philosophical stance on social norms, and this has been especially true since harm reductionists began emphasizing the structural forces that shape and fuel drug use.

Until Canada’s addiction medicine community facilitates a more robust and open conversation about the politicization of research, and the divided—and inescapably political—nature of their work, the national debate on the overdose crisis will be shambolic. This will have negative downstream impacts on policymaking and, ultimately, people’s lives.

Our content is always free – but if you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism,

consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

-

Frontier Centre for Public Policy2 days ago

Frontier Centre for Public Policy2 days agoRichmond Mayor Warns Property Owners That The Cowichan Case Puts Their Titles At Risk

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoMark Carney Seeks to Replace Fiscal Watchdog with Loyal Lapdog

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoSluggish homebuilding will have far-reaching effects on Canada’s economy

-

COVID-191 day ago

COVID-191 day agoMajor new studies link COVID shots to kidney disease, respiratory problems

-

Daily Caller2 days ago

Daily Caller2 days agoLaura Ingraham’s Viral Clash With Trump Prompts Her To Tell Real Reasons China Sends Students To US

-

Business1 day ago

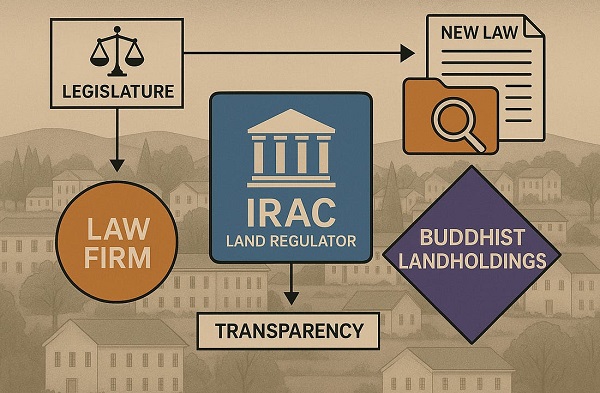

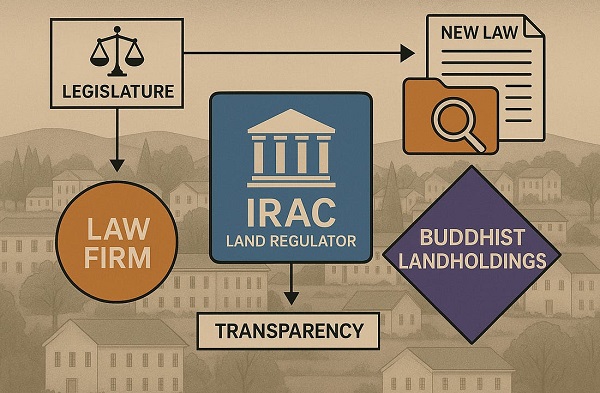

Business1 day agoP.E.I. Moves to Open IRAC Files, Forcing Land Regulator to Publish Reports After The Bureau’s Investigation

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoBondi and Patel deliver explosive “Clinton Corruption Files” to Congress

-

International24 hours ago

International24 hours agoState Department designates European Antifa groups foreign terror organizations