Frontier Centre for Public Policy

Budget 2024 as the eve of 1984 in Canada

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

Those who claim there are unmarked burials have painted themselves into a corner. If there are unmarked burials, there have had to be murders because why else would anyone attempt to conceal the deaths?

The Federal Government released its Budget 2024 last week. In addition to hailing a 181% increase in spending on Indigenous priorities since 2016, “Budget 2024 also proposes to provide $5 million over three years, starting in 2025-26, to Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada to establish a program to combat Residential School denialism.” Earlier this spring, the government proclaimed:

The government anticipates the Special Interlocutor’s final report and recommendations in spring 2024. This report will support further action towards addressing the harmful legacy of residential schools through a framework relating to federal laws, regulations, policies, and practices surrounding unmarked graves and burials at former residential schools and associated sites. This will include addressing residential school denialism.

Like “Reconciliation,” the exact definition of what the Federal government means by “residential school denialism” is not clear. In this vague definition, there is, of course, a potential for legislating vindictiveness.

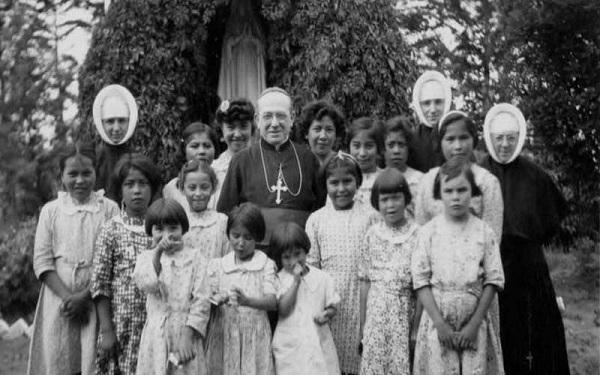

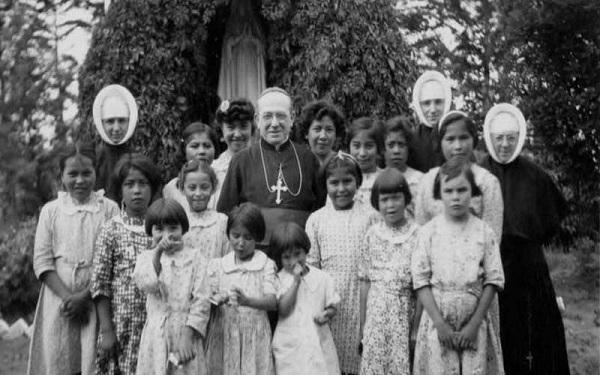

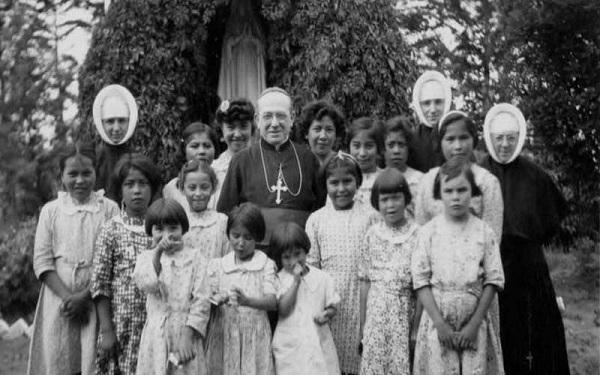

What further action is needed to address “the harmful legacy of residential schools” except to enforce a particular narrative about the schools as being only harmful? Is it denialism to point out that many students, such as Tomson Highway and Len Marchand, had positive experiences at the schools and that their successful careers were, in part, made possible by their time in residential school? If the study of history is subordinated to promoting a particular political narrative, is it still history or has it become venal propaganda?

Since the sensational May 27, 2021, claim that 215 children’s remains had been found in a Kamloops orchard, the Trudeau government has been chasing shibboleths. The Kamloops claim remains unsubstantiated to this day in two glaring ways: no names of children missing from the Kamloops IRS (Indian Residential Schools) have been presented and no human remains have been uncovered. For anyone daring to point out this absence of evidence, their reward is being the target of a witch hunt. As we recently witnessed in Quesnel, B.C., to be labeled as a residential school denialist is to be drummed out of civil society.

If we must accept a particular political narrative of the IRS as the history of the IRS, does our freedom of conscience and speech have any meaning?

To the discredit of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, fictions of missing and murdered children circulating long before the Commission’s inception were subsumed by the TRC (Truth and Reconciliation Commission). Unmarked graves and burials were incorporated into the TRC’s work as probable evidence of foul play. In the end, the TRC found no evidence of any murders committed by any staff against any students throughout the entirety history of the residential schools. Unmarked graves are explained as formerly marked and lawful graves that had since become lost due to neglect and abandonment. Unmarked burials, if they existed, could be construed as evidence of criminal acts, but such burials associated with the schools have never been proven to exist.

Those who claim there are unmarked burials have painted themselves into a corner. If there are unmarked burials, there have had to be murders because why else would anyone attempt to conceal the deaths? If there are thousands of unmarked burials, there are thousands of children who went missing from residential schools. How could thousands of children go missing from schools without even one parent, one teacher, or one Chief coming forward to complain?

There are, of course, neither any missing children nor unmarked burials and the Special Interlocutor told the Senate Committee on Indigenous People: “The children aren’t missing; they’re buried in the cemeteries. They’re missing because the families were never told where they’re buried.”

Is it denialism to repeat or emphasize what the Special Interlocutor testified before a Senate Committee? Is combating residential school denialism really an exercise in policing wrongthink? Like the beleaguered Winston in Orwell’s 1984, it is impossible to keep up with the state’s continual revision of the past, even the recent past.

For instance, the TRC’s massive report contains a chapter on the “Warm Memories” of the IRS. Drawing attention to those positive recollections is now considered “minimizing the harms of residential schools.”

In 1984, the state sought to preserve itself through historical revision and the enforcement of those revisions. In the Trudeau government’s efforts to enforce a revision of the IRS historical record, the state is not being preserved. How could it be if the IRS is now considered to be a colossal genocide? The intent is to preserve the party in government and if it means sending Canada irretrievably down a memory hole as a genocidaire, so be it.

Michael Melanson is a writer and tradesperson in Winnipeg.

Crime

How Global Organized Crime Took Root In Canada

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

Weak oversight and fragmented enforcement are enabling criminal networks to undermine Canada’s economy and security, requiring a national-security-level response to dismantle these systems

A massive drug bust reveals how organized crime has turned Canada into a source of illicit narcotics production

Canada is no longer just a victim of the global drug trade—it’s becoming a source. The country’s growing role in narcotics production exposes deep systemic weaknesses in oversight and enforcement that are allowing organized crime to take root and threaten our economy and security.

Police in Edmonton recently seized more than 60,000 opium poppy plants from a northeast property, one of the largest domestic narcotics cultivation operations in Canadian history. It’s part of a growing pattern of domestic production once thought limited to other regions of the world.

This wasn’t a small experiment; it was proof that organized crime now feels confident operating inside Canada.

Transnational crime groups don’t gamble on crops of this scale unless they know their systems are solid. You don’t plant 60,000 poppies without confidence in your logistics, your financing and your buyers. The ability to cultivate, harvest and quietly move that volume of product points to a level of organization that should deeply concern policymakers. An operation like this needs more than a field; it reflects the convergence of agriculture, organized crime and money laundering within Canada’s borders.

The uncomfortable truth is that Canada has become a source country for illicit narcotics rather than merely a consumer or transit point. Fentanyl precursors (the chemical ingredients used to make the synthetic opioid) arrive from abroad, are synthesized domestically and are exported south into the United States. Now, with opium cultivation joining the picture, that same capability is extending to traditional narcotics production.

Criminal networks exploit weak regulatory oversight, land-use gaps and fragmented enforcement, often allowing them to operate in plain sight. These groups are not only producing narcotics but are also embedding themselves within legitimate economic systems.

This isn’t just crime; it’s the slow undermining of Canada’s legitimate economy. Illicit capital flows can distort real estate markets, agricultural valuations and financial transparency. The result is a slow erosion of lawful commerce, replaced by parallel economies that profit from addiction, money laundering and corruption. Those forces don’t just damage national stability—they drive up housing costs, strain health care and undermine trust in Canada’s institutions.

Canada’s enforcement response remains largely reactive, with prosecutions risk-averse and sentencing inadequate as a deterrent. At the same time, threat networks operate with impunity and move seamlessly across the supply chain.

The Edmonton seizure should therefore be read as more than a local success story. It is evidence that criminal enterprise now operates with strategic depth inside Canada. The same confidence that sustains fentanyl synthesis and cocaine importation is now manifesting in agricultural narcotics production. This evolution elevates Canada from passive victim to active threat within the global illicit economy.

Reversing this dynamic requires a fundamental shift in thinking. Organized crime is a matter of national security. That means going beyond raids and arrests toward strategic disruption: tracking illicit finance, dismantling logistical networks that enable these operations and forging robust intelligence partnerships across jurisdictions and agencies.

It’s not about symptoms; it’s about knocking down the systems that sustain this criminal enterprise operating inside Canada.

If we keep seeing narcotics enforcement as a public safety issue instead of a warning of systemic corruption, Canada’s transformation into a threat nation will be complete. Not because of what we import but because of what we now produce.

Scott A. McGregor is a senior fellow with the Frontier Centre for Public Policy and managing partner of Close Hold Intelligence Consulting Ltd.

Business

The Payout Path For Indigenous Claims Is Now National Policy

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

By Tom Flanagan

Ottawa’s refusal to test Indigenous claims in court is fuelling a billion-dollar wave of settlements and legal copycats

First Nations led the charge. Now the Métis are catching up. Ottawa’s legal surrender strategy could make payouts the new national policy.

Indigenous class-action litigation seeking compensation for historical grievances began in earnest with claims related to Indian Residential Schools. The federal government eventually chose negotiation over litigation, settling for about $5-billion with “survivors.” Then–prime minister Stephen Harper hoped this would close the chapter, but it opened the floodgates instead. Class actions have followed ever since.

By 2023, the federal government had paid or committed $69.6-billion in 2023 dollars to settle these claims. What began with residential schools expanded into day schools, boarding homes, the “Sixties Scoop,” unsafe drinking water, and foster-care settlements.

Most involved status Indians. Métis claims had generally been unsuccessful—until now.

Download the Essay. (4 pages)

Tom Flanagan is professor emeritus of political science at the University of Calgary and a senior fellow of the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

-

COVID-1917 hours ago

COVID-1917 hours agoNew report warns Ottawa’s ‘nudge’ unit erodes democracy and public trust

-

Great Reset2 days ago

Great Reset2 days agoEXCLUSIVE: A Provincial RCMP Veterans’ Association IS TARGETING VETERANS with Euthanasia

-

Health2 days ago

Health2 days agoDisabled Canadians petition Parliament to reverse MAiD for non-terminal conditions

-

Crime1 day ago

Crime1 day agoHow Global Organized Crime Took Root In Canada

-

Daily Caller2 days ago

Daily Caller2 days agoSpreading Sedition? Media Defends Democrats Calling On Soldiers And Officers To Defy Chain Of Command

-

Digital ID2 days ago

Digital ID2 days agoLeslyn Lewis urges fellow MPs to oppose Liberal push for mandatory digital IDs

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoThe Payout Path For Indigenous Claims Is Now National Policy

-

Energy1 day ago

Energy1 day agoExpanding Canadian energy production could help lower global emissions