Aristotle Foundation

B.C. Supreme Court takes an axe to private property rights

Native rights are constitutionally guaranteed; property rights are not. When courts recognize Aboriginal title, it’s easy to see who will win

Think you own your private property? Well think again, as a recent court decision has thrown the entire basis of property ownership into chaos in British Columbia.

In the ultimate “land acknowledgement,” the B.C. Supreme Court released a bombshell judgment last week declaring Aboriginal title for the Cowichan Tribes of Vancouver Island to around 325 hectares on the mainland, in the city of Richmond.

This is the first time a court has declared Aboriginal title over private land in the province, setting a deeply concerning precedent if the ruling is not successfully overturned following an appeal promised by B.C.’s attorney general.

In another troubling precedent, the court also declared that fee simple land titles — the typical form of private property ownership in Canada — in the area are “defective and invalid,” on the basis that the Crown had no authority to issue them in the first place.

As constitutional law professor Dwight Newman points out, if past fee simple grants in areas of Aboriginal title claims are inherently invalid, “then the judgment has a much broader implication that any privately owned lands in B.C. may be subject to being overridden by Aboriginal title.”

The only thing preventing the judge from making a similar declaration over privately held land in the new Aboriginal title area is the fact that the Cowichan did not ask for a declaration to this effect.

But nothing prevents that from happening in the future if the judgment stands. The judge actually contemplates this very scenario, writing that, “Fee simple interests … will go unaffected in practice when Aboriginal title is recognized over that land, unless or until the Aboriginal title holder successfully takes remedial action in respect of the fee simple interests.”

In short, while most private landowners assume their title to their own land is bulletproof, the ruling states: It “cannot be said that a registered owner’s title under the (Land Title Act) is conclusive evidence that the registered owner is indefeasibly entitled to that land as against Aboriginal title holders and claimants.”

It’s worth noting that the claim was contested by two mainland Indigenous groups, the Musqueam and Tsawwassen First Nations, both of whom lay claim to the same land. This highlights the issue of competing claims in a province where the vast majority of the land mass is claimed as traditional territory by one or more of B.C.’s 200-plus Indigenous groups.

While two previous decisions by the Supreme Court of Canada recognized Aboriginal title in British Columbia (Tsilhqot’in in 2014 and Nuchatlaht in 2024), neither declared it over privately held lands as this one does.

Even as the B.C. government has promised to appeal the decision, it has been pursuing similar policies outside the courts. The province controversially overlaid Aboriginal title on private land with its problematic Haida Nation Recognition Act in 2024. The act was specifically referenced by the plaintiffs in the Cowichan case, and the judge agreed that it illustrated how Aboriginal title and fee simple can “coexist.”

This is a questionable assertion given the numerous legal concerns. As one analysis explains, private property interests and the implementation of Aboriginal title are ultimately at odds: “The rights in land which flow from both a fee simple interest and Aboriginal title interest … include exclusive rights to use, occupy and manage lands. The two interests are fundamentally irreconcilable over the same piece of land.”

While the government claims it adequately protected private property rights in the Haida agreement, Aboriginal title is protected under the Constitution, while private property rights are not. When these competing interests are inevitably brought before the courts, it’s easy to imagine which one will prevail.

The fact that B.C. Premier David Eby said last year that he intended to use the Haida agreement as a “template” for other areas of B.C. stands in marked contrast with his sudden interest in an appeal as a means of preserving clear private property titles in the wake of this politically toxic ruling.

Indeed, Eby’s government continues to negotiate similar agreements elsewhere, including with the shíshálh Nation on B.C.’s Sunshine Coast, even as government documents admit that Aboriginal title includes the right to “exclusively use and occupy the land.”

Eby’s commitment to an appeal suggests he may have learned from his costly refusal to appeal a 2021 B.C. Supreme Court decision, which found that excessive development had breached the treaty rights of the Blueberry River First Nation. Eby’s government chose to pay out a $350-million settlement to avoid further litigation, a move that ultimately backfired when the two parties ended up back in court.

But for now, the consequences of the Cowichan decision have created considerable uncertainty for property owners, businesses and general market confidence. The judge’s own words sum it up: “The question of what remains of Aboriginal title after the granting of fee simple title to the same lands should be reversed. The proper question is: what remains of fee simple title after Aboriginal title is recognized in the same lands?”

If there’s one positive aspect to this decision, it’s that it is so extreme, it will force the Eby government’s radical Indigenous policies onto the public agenda as awareness builds over what’s at stake.

From its incessant land acknowledgements, to MLAs referring to non-Indigenous British Columbians as “uninvited guests,” to its embrace of the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples and its land back policies, to undemocratic land use planning processes and the overlaying of Aboriginal title on private lands, B.C. government policy has long been headed in exactly this direction.

Now, a reckoning is coming, and it’s of the government’s own creation. The broader issue will soon overtake all others in the public eye, and the premier must decide now whether he’ll start walking things back, or double down on his disastrous course.

Caroline Elliott is a senior fellow with the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy and sits on the board of B.C.’s Public Land Use Society.

Photo: WikiCommons.

Aristotle Foundation

Judges should interpret law—not make public policy from the bench

By Bronwyn Eyre

To understand how politicized Canada’s courts have become, one must understand how judges once viewed their role—not as policymakers, but interpreters of laws and the Constitution.

In 1982, the late Supreme Court of Canada Chief Justice Bora Laskin said judges have “no freedom of speech to address political issues that have nothing to do with judicial duties… Absolute abstention from political activity is one of the guarantees of impartiality, integrity and independence.”

That was then. Post-Charter (also introduced in 1982), too many judges have internalized the “living tree doctrine”—that the Constitution continually adapts to “evolving” social and political contexts—and are increasingly advancing expansive positions based on political ideology.

The result is that governments, elected to pass legislation, are unable to tackle important issues from homelessness to climate policy without being overruled by the courts. They are spending millions fighting Charter challenges—often brought by only a handful of complainants.

Just recently, Ontario’s Superior Court sided with just two University of Toronto students to stop the provincial government from dismantling bike lanes to ease traffic congestion. Under the Charter’s Section 7 (Life, Liberty, and Security of the Person), the government cannot, ruled the court, “knowingly make the streets less safe.” Talk about begging the question. Meanwhile, an effort by the Ontario government to dismantle drug injection sites, including near schools and daycares, is on pause pending another Section 7 legal challenge.

In another case with major precedent impact across the country, Ontario’s Superior Court held in 2023 that homeless encampments must effectively remain in place until shelter spaces are found for every resident. The City of Waterloo’s attempt, via municipal bylaw, to dismantle a 70-structure homeless encampment on city property was held to violate—once again—Section 7 of the Charter. Stated the court: “The constitutional right to shelter is invoked when the number of homeless exceeds available and truly accessible shelter spaces.”

The same court agreed in 2023 with just seven environmental activists challenging Ontario’s climate plan that it is an “indisputable fact that Ontarians are experiencing an increased risk of death” from climate change.

According to Ecojustice lawyer Fraser Thomson, who represented the activists, the ruling “effectively boxes Ontario in and subjects its climate record to full Charter scrutiny.” The Supreme Court recently denied Ontario’s appeal request in the case, which is now heading back to court. This, as similar youth-led climate cases are making their way through the courts in other provinces.

Meanwhile, last month’s International Court of Justice’s ruling that a clean environment is a “human right” was hailed by climate activists as a major victory which will inform future court decisions and legal challenges—including to the new federal major projects Bill C-5.

Courts ought not be the exclusive arbiters of social and economic policy—genuine concerns about issues such as climate policy or homelessness, notwithstanding.

So, what to do?

For now, premiers are increasingly looking to the Notwithstanding Clause. Routinely called the “nuclear option,” it’s actually a perfectly legitimate use of Section 33 of the Charter—and the most powerful tool governments have to assert parliamentary sovereignty.

A constitutional scholar and former NDP premier of Saskatchewan, Allan Blakeney, would agree. Blakeney fought hard for the clause’s inclusion in the Charter and wrote, in 2010, that the state could invoke it for “economic or social reasons, or because other rights are more important.”

Let’s not forget that from 1982 to 1985, Quebec “notwithstood” everything—and that doesn’t mean one must agree with its every usage. The point, à la Blakeney, is that it is the only mechanism to reassert some parliamentary supremacy. More recently, Quebec and Alberta have talked about forming an “autonomy alliance,” which would create a “special deliberation mechanism for legislative bills and include the Notwithstanding Clause to dissuade court challenges.”

If only such a mechanism could reform federal catch-and-release laws.

In 2023, Justice Harrison Arrell released violent offender Randall McKenzie, citing Criminal Code-embedded bail rules that mandate “vulnerable population” considerations. “It’s a very iffy case,” Arrell wrote. “I appreciate all the violence in his record, but part of that is his native background, education and employment opportunities.”

Six months later, McKenzie killed OPP Constable Greg Pierzchala. The shocking case highlighted 2018 federal Criminal Code amendments, which codified the “principle of restraint”—that bail must be granted at the “earliest possible opportunity” on the “least onerous conditions.”

Despite limited subsequent tweaks to the Criminal Code by the federal government, nothing fundamentally has changed.

When asked whether Canada is “soft on crime,” Sean Fraser, Canada’s new minister of justice and attorney general, said we “can’t operate in the space of slogans and soundbites.”

Indeed.

Hon. Bronwyn Eyre, LLB, is a Senior Fellow with the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy, Saskatchewan’s former minister of justice and attorney general—the first female to hold each position—and a former long-serving minister of energy.

Photo: iStock.

Alberta

Alberta court’s ‘gender’ ruling ignores evidence and common sense.

Justice or ideology?

Justice Kuntz’ judgment makes for astonishing reading. For instance, stating “there is nothing speculative about this evidence” blithely ignores the alarm bells set off by medical authorities in the United Kingdom, Finland, Sweden and elsewhere who went in search of such evidence and found it to be grossly lacking. Those countries subsequently enacted severe restrictions on the provision of puberty blockers and cross-gender hormones to youth.

Last November, the Alberta Medical Association (AMA) released a statement taking aim at the Smith government for its new legislation banning puberty blockers and hormone therapy for trans-identifying youth. The AMA stated, among other things: “There is no place for the government in the medical decisions being made by parents and their children in conjunction with physicians.”

In an ideal world, the AMA would be absolutely correct—just as in an ideal world there would be no hunger, poverty, discrimination and violence.

But we don’t live in that ideal world. We live in an imperfect world where even the most well-intentioned physicians (and physician groups) get things wrong. Consider only the sad histories of frontal lobotomies, the Tuskegee syphilis experiments, the thalidomide disaster, the origins of the opioid crisis, and so on.

Opponents of the Alberta government’s gender legislation (a cohort which includes the Canadian Medical Association and the Canadian Pediatric Society) surely felt vindicated the other week when Justice Allison Kuntz issued an injunction suspending Alberta’s new law. (Full disclosure: I and four other pediatric specialists provided affidavits in support of the government’s position.) In her ruling favouring the several parties that jointly sued the government, Justice Kuntz wrote:

I find that there will be irreparable harm to gender diverse youth if an injunction is not granted. The evidence shows that the Ban will cause irreparable harm by causing gender diverse youth to experience permanent changes to their body that do not align with their gender identity. There is nothing speculative about this evidence.

Justice Kuntz’ judgment makes for astonishing reading. For instance, stating “there is nothing speculative about this evidence” blithely ignores the alarm bells set off by medical authorities in the United Kingdom, Finland, Sweden and elsewhere who went in search of such evidence and found it to be grossly lacking. Those countries subsequently enacted severe restrictions on the provision of puberty blockers and cross-gender hormones to youth.

Astonishing, too, is Justice Kuntz’ favourable emphasis of the World Professional Association for Transgender Health (WPATH) guidelines, while ignoring the grave concerns that exist regarding evidence-free “gender affirmation” practices.

Justice Kuntz does devote space to summarizing the Cass Review—an exhaustive four-year investigation by esteemed pediatrician Dr. Hilary Cass into gender medicine practices in the U.K., which led to the shuttering of that country’s Tavistock gender clinic and a ban on the provision of puberty blockers to youth. She concedes that the Alberta government’s expert evidence is “consistent with the Cass Review”, yet in the end, inexplicably, sets this aside in favour of the complainants’ view that the legislation may “irreparably” harm children, rather than the “gender-affirming” model of care.

And Justice Kuntz omits entirely any mention of the twin Canadian systematic reviews authored this year by Dr. Gordon Guyatt’s group at McMaster University, which also exposed the lack of evidence for “gender-affirming” care. Nor does she mention the U-turn on gender practices initiated by Dr. Riittakerttu Kaltiala of Finland, the very founder of Finland’s gender medicine service.

On her weekend radio show, Alberta Premier Danielle Smith reacted to Justice Kuntz’ ruling: “The court… said that they think that there will be irreparable harm if the law goes ahead. I feel the reverse.”

I and many other medical professionals (many of whom dare not speak openly) agree with the premier. Initiating puberty blockers in gender-confused children sets them on a pathway, which in most cases leads on to cross-gender hormones and in some instances to body-revising surgery. This is a pathway of no return, paved with lifelong medicalization and infertility— implications that adolescents are grossly ill-equipped to comprehend.

Those of us harbouring grave concerns will not use the hyperbolic language of trans activists, such as “denying the right of trans-identified youth to exist.” On the contrary; we want only for them to exist in the most healthy way possible, based on the best available evidence. We want them to become comfortable, if possible, in the body in which they were born—an outcome evidence has shown to be eminently achievable with appropriate counselling and “watchful waiting.”

On the other hand, the best available evidence for the “gender-affirming” approach is scant, notwithstanding Justice Kuntz’ capitulation to the unsupported conclusions of the complainants. And as Dr. Cass and others have discovered, the evidence suggests that the gender-affirming drug-administering model of care does more harm than good.

Justice Kuntz ruling is an injunction, to be clear. It isn’t a final ruling—full adjudication will play out in court in the coming months. One can only hope that, after a complete and proper airing of the issue, sanity and level-headedness will prevail despite the toxic politicization that has poisoned the debate.

That would be, well, ideal.

Dr. J. Edward Les is a Calgary pediatrician and senior fellow with the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy. His new book is “Cloudy with a Risk of Children: Straight Talk from the Pediatric ER.” Photo: iStock.

-

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days ago

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days agoCanada To Revive Online Censorship Targeting “Harmful” Content, “Hate” Speech, and Deepfakes

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoOrthodox church burns to the ground in another suspected arson in Alberta

-

Fraser Institute2 days ago

Fraser Institute2 days agoAboriginal rights now more constitutionally powerful than any Charter right

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day ago$150 a week from the Province to help families with students 12 and under if teachers go on strike next week

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoNew PBO report underscores need for serious fiscal reform in Ottawa

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoArab and Muslim nations rally behind Trump’s Gaza peace plan

-

Business1 day ago

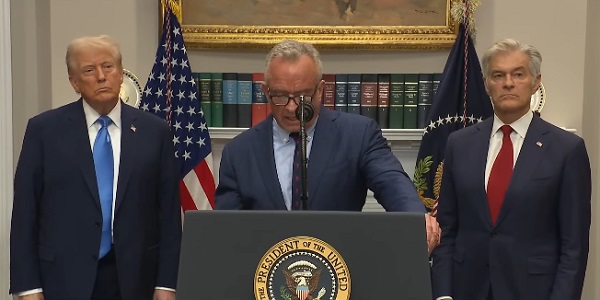

Business1 day agoPfizer Bows to Trump in ‘Historic’ Drug Price-Cutting Deal

-

Agriculture2 days ago

Agriculture2 days agoCarney’s nation-building plan forgets food