Fraser Institute

B.C. Indigenous land claims decision leaves British Columbians in limbo

From the Fraser Institute

The Cowichan, who are based mainly on Vancouver Island, claimed they had a village on an island that is now part of Richmond that they used seasonally. They had to prove with evidence that they were fearsome enough that other groups—like the Musqueam and Tsawwassen, who incidentally were both part of the opposition to the Cowichan claim—would have been scared and thus reluctant to use the claimed area when the Cowichan were away.

The recent decision of the British Columbia Supreme Court in Cowichan Tribes v Canada (Attorney General) (cited as 2025 BCSC 1490) granting a declaration of Aboriginal title over city-owned land in Richmond and fishing rights in the Fraser River has already drawn attention and concern.

This is because the judgment’s reasoning on Aboriginal title has potentially widespread implications for private property in B.C., and perhaps elsewhere. At the same time, the judgment is also totally inaccessible for most readers. At a monster length of more than 3,700 paragraphs, it does not yield legal guidance easily.

The judgment comes after a trial that started in 2019, with more than 500 trial days. The judgment lists out more than 80 lawyers involved so far. It was the longest trial in Canadian history, and the case will probably ultimately reach the Supreme Court of Canada—perhaps with a decision by the end of the decade.

Estimating the likely costs based on the length of proceedings, and normal legal fees, I will not be surprised if overall legal costs in the Cowichan Tribes case approach or even exceed $100 million by the time all is said and done.

What does $100 million of such spending get you these days? A few things.

First, and explaining significant parts of the expense, it got a lot of detailed evidence from documents, from experts, from Aboriginal oral history, and other forms that the trial judge, Madam Justice Young, considered against the established Aboriginal title test. In other words, the trial allowed a multitude of sources, many new, for the trial judge to try to apply the existing rules on Aboriginal title.

That test looks for whether a claimant group has proven “sufficient” and “exclusive” occupation of land as of just prior to the date of assertion of European/Canadian sovereignty—in this part of B.C., that date is 1846. The Cowichan, who are based mainly on Vancouver Island, claimed they had a village on an island that is now part of Richmond that they used seasonally. They had to prove with evidence that they were fearsome enough that other groups—like the Musqueam and Tsawwassen, who incidentally were both part of the opposition to the Cowichan claim—would have been scared and thus reluctant to use the claimed area when the Cowichan were away. Sorting through these facts and other elements pertinent to the Aboriginal title test took massive amounts of evidence and time.

Second, the spending includes consideration of various defences that parties to the case mounted. The federal lawyers, the provincial lawyers, and City of Richmond lawyers all made different arguments. Both the federal and provincial lawyers were restricted in what they could argue, based on a combination of their own policies and on the judge’s rejection of some of their arguments as inconsistent with other legal acts, such as B.C.’s recognition of title in the Haida Agreement. This is an important recognition of how the trial judge’s decision was influenced by discretionary provincial policy in the province, namely its recognition of the Haida Nation’s title on their claimed land.

The City of Richmond was less restricted in its defence but critically failed with portions of its defence that might apply to private landowners. For example, the lands the City of Richmond owned were determined to not have been acquired “for value,” which means that the City didn’t buy them. The failure of meeting this test means the City of Richmond was not afforded the significant protection in property law that many private landowners would receive (under a technical category of “bona fide purchasers for value”).

Third, the spending gets you a decision that included some unclear paragraphs that say there will be interesting questions to be faced down the road, including what happens when there’s an Aboriginal title claim directly over privately owned land. Some text from the decision in the case suggest Aboriginal title might take priority over any other property interest, but private landowners will have a future chance to invoke defences such as the “bona fide purchaser for value” concept. Despite the fact the Cowichan avoided these issues for now by not asking for a declaration concerning any private land, those cases are coming. The broader trajectory is precisely towards that clash, and there are active cases of that type elsewhere, including over major private landholdings throughout New Brunswick.

There’s not any definitive legal clarity from the judgment on this crucial point of how Aboriginal title and private property interact. For $100 million, the trial delivered lingering uncertainty and heightened risks on the legal status of property, which influences the economy and residents across the province, not just those directly involved in the case.

This issue has been key in motivating a provincial government appeal, which is unlikely to take less than a year to resolve and could take two or even three years, and even then it’s likely to move on to the Supreme Court of Canada. Until then, British Columbians, including Indigenous Peoples, will continue to face heightened uncertainty and the economic costs it imposes.

Business

Carney government plans to muddy the fiscal waters in upcoming budget

From the Fraser Institute

By Jake Fuss and Grady Munro

Rather than directly spend money on critical infrastructure such as roads, bridges, ports or even electricity grids—things that traditionally are considered capital investments—the government plans to spend money on subsidies and tax breaks to corporations (i.e. corporate welfare) under the umbrella of “capital investment”

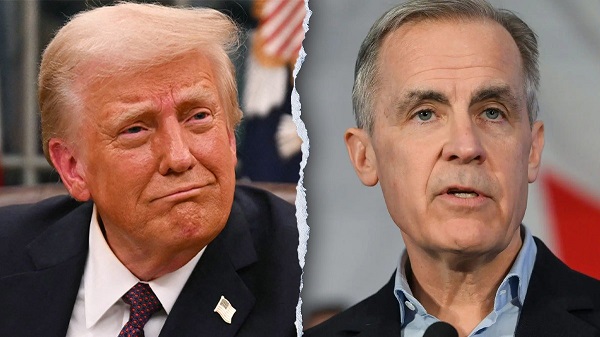

The Carney government’s long-awaited first budget is almost here—expected Nov. 4—but Canadians may not recognize what they get. Early on, the new government promised a new approach to spending. Thanks to a decade of record-breaking spending under Justin Trudeau, the federal deficit sits at a projected $48.3 billion while total debt has eclipsed $2.1 trillion. But the Carney government’s plan announced this week appears to rely on accounting maneuvers rather than any substantive spending reductions.

According to the latest details released by the government, the Carney government will separate spending into two categories: “operating spending” and “capital investment.” Within this framework, the government plans to balance the “operating budget” within three years.

But of course, if the government eventually balances the operating budget, that doesn’t mean it will stop borrowing money to pay for“capital investment”—a new category of spending the government can define and expand whenever it deems necessary.

Currently, according to the government, capital investment will include any spending or tax expenditures (e.g. tax credits and deductions) that “contribute to capital formation”—the creation of assets (such as machinery or equipment) that improve the ability of workers to produce goods and services.

In other words, rather than directly spend money on critical infrastructure such as roads, bridges, ports or even electricity grids—things that traditionally are considered capital investments—the government plans to spend money on subsidies and tax breaks to corporations (i.e. corporate welfare) under the umbrella of “capital investment,” so long as this spending will somehow “encourage” capital formation. But clearly, corporate welfare doesn’t belong in the same category as the expansion of a critical port, for example, and the government shouldn’t pretend that it does.

Put simply, because the term “capital investment” is so broad and malleable, the government can seemingly use it whenever it wants. For example, to meet NATO’s spending target of 2 per cent of GDP, a key point of contention in Carney’s negotiations with President Trump, the Carney government could (inaccurately) categorize some defence spending as capital spending. And in fact, the Parliamentary Budgetary Officer—Ottawa’s fiscal watchdog—views the Carney government’s definition as “overly expansive” and suggests the inclusion of corporate tax breaks and subsidies will “overstate” the government’s actual contribution to the creation of capital.

This approach by the Carney government will not help Canadians understand the true state of federal finances. While Finance Minister François-Philippe Champagne recently said that the “deficit and the debt will be recorded in the same manner as in previous budgets,” on budget day and beyond the government will undoubtedly focus on the operating budget when communicating to Canadians. So, the government will only tell part of the story.

After years of fiscal mismanagement with large increases in spending and debt under the Trudeau government, Canadians need a government willing to make the tough decisions necessary to get federal finances back in shape. But the Carney government appears poised to shirk accountability and use tricks to cloud the true state of federal finances.

Alberta

Alberta government’s pipeline proposal reveals truth nature of oil and gas opponents

From the Fraser Institute

Earlier this month, when Alberta Premier Danielle Smith announced that her government, in conjunction with major players in the oilsands, would propose a pipeline to carry Alberta’s products to tidewater off Canada’s west coast, she may have called the Carney government’s bluff (and the bluff of any other government that might be bluffing about pipelines).

In June, the Carney government passed Bill C-5 to purportedly eliminate the gridlock that prevents the construction of major energy infrastructure. But the government’s first list of projects to get the Bill C-5 treatment did not include any oil or gas pipelines (which was no surprise, in light of Canada’s hostile regulatory landscape that deters private-sector companies from investing time and money). In response to Smith’s announcement, federal Natural Resources Minister Tim Hodgson said any proposal for a pipeline must include “meaningful consultations with Indigenous rights holders” and close partnerships with “all affected jurisdictions.”

Meanwhile, in British Columbia, one of those “affected jurisdictions,” Premier David Eby is essentially denying that Smith’s proposal has significant private-sector support, implying it will require federal spending and that it’s a “direct threat to the kind of economy we are trying to build.” And yet, back in June, Eby said he was open to the idea of another privately-funded pipeline to tidewater in northern B.C., noting only that he doesn’t support “tens of billions of dollars in federal subsidy going to build this new pipeline when we already own a pipeline that empties into British Columbia,” referring to the Trans Mountain pipeline. In other words, it sounds like Eby has changed his tune.

In Quebec, Premier François Legault said in February that his government might be open to a proposed oil pipeline (Energy East) from Alberta—“For the moment, there is no project on the table,” he said. “If there is a project on the table, we will look at it.” Fast-forward to today. When asked about Smith’s proposal, leader of the Bloc Quebecois, Yves-François Blanchet (a close ally of Legault’s), said “Let’s imagine that Quebec is an independent and free country. We will go on the world stage to say that Alberta is destroying the environment of the whole planet.”

Clearly, while the federal government and key provincial governments have implied that they’re open to new pipelines (albeit, under an ever-changing roster of conditions), Premier Smith’s proposal has seemingly revealed the truth. They sound like the same implacable opponents of oil and gas development, in submission to the international climate change movement’s zero-tolerance policy for fossil fuels, that have dominated in Canada for a decade.

-

National7 hours ago

National7 hours agoCanada’s birth rate plummets to an all-time low

-

Crime6 hours ago

Crime6 hours agoPierre Poilievre says Christians may be ‘number one’ target of hate violence in Canada

-

Alberta5 hours ago

Alberta5 hours agoJason Kenney’s Separatist Panic Misses the Point

-

Automotive8 hours ago

Automotive8 hours agoBig Auto Wants Your Data. Trump and Congress Aren’t Having It.

-

Aristotle Foundation2 days ago

Aristotle Foundation2 days agoEfforts to halt Harry Potter event expose the absurdity of trans activism

-

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days ago

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days agoCanada’s Humility Gene: Connor Skates But Truckers Get Buried

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days ago“It is intellectually dishonest not to acknowledge the … erosion of trust among global customers in Canada’s ability to deliver another oil pipeline.”

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoIn the halls of Parliament, Ellis Ross may be the most high-profile advocate of Indigenous-led development in Canada.