Fraser Institute

B.C. Aboriginal agreements empower soft tyranny of legal incoherence

From the Fraser Institute

By Bruce Pardy

In April 2024, the British Columbia government agreed to recognize and affirm the Haida Nation’s Aboriginal title to the archipelago on Canada’s west coast. In December, Ottawa did likewise. These agreements signal danger, and not just on Haida Gwaii.

The agreements tell two conflicting stories. One story is that a new era has begun. Colonial occupation has ended. Haida Gwaii will be governed in accordance with Haida Aboriginal title. But the second story is that private property will be honoured, federal, provincial and local governments will continue to exercise their jurisdiction, and the province will continue to provide and pay for health, education, transportation and fire and emergency services.

On Haida Gwaii, everything has changed, but nothing will change. Though both stories cannot be true, it’s impossible to tell which is false in what respects. Who has jurisdiction over what? If you use your land in a way that complies with local government zoning but the Council of the Haida Nation prohibits it, is it prohibited or permitted? If the council requires visitors to be vaccinated, but the province does not, must they be vaccinated or not? The agreements don’t say.

When jurisdictional conflicts arise under the agreements, they are to be “reconciled” in a transition process. But that process will be decided under Haida law, which is not codified or legislated. Only those with status and authority can say what it is. The legal meaning of the Haida Gwaii agreements therefore cannot be ascertained in any objective sense.

The agreements say private property on Haida Gwaii will be honoured. But private property is incompatible with Aboriginal title. According to the Supreme Court of Canada, Aboriginal title is communal: it consists of the right of a group to exclusive use and occupation of land, but with inherent limits on that use. Land subject to Aboriginal title “cannot be alienated except to the Crown or encumbered in ways that would prevent future generations of the group from using and enjoying it,” the Court wrote in 2014. “Nor can the land be developed or misused in a way that would substantially deprive future generations of the benefit of the land.” If so, the promises in the agreement conflict. Land subject to Aboriginal title cannot be given away or sold, either as a single piece or in bits, except to the Crown. But when land is surrendered to the Crown, Aboriginal title is extinguished on that land. If Haida Gwaii really is subject to Aboriginal title, then no one can own parts of it privately.

Around 5,000 people live on Haida Gwaii, about half Haida. In April 2024, they voted 95 per cent in favour of the B.C. agreement at a special assembly in which non-Haida residents had no say. The agreements create two classes of citizens—one with political status, the other without, depending on people’s lineage.

According to B.C. Premier David Eby, the Haida Gwaii agreement is a template for the rest of the province. In early 2024, the government proposed to amend the province’s Land Act to empower hundreds of First Nations to make joint decisions with the minister on how Crown land—around 95 per cent of the province—is used. That would have given First Nations a veto over the use of public land. Public backlash forced the government to withdraw its proposal, which it did in February 2024. But it has not backed off its objectives and instead has embarked on a series of agreements granting title to, or control over, specific territories to specific Aboriginal groups. Typically, these are negotiated quietly and announced after the fact.

For example, in late January, the government revealed it had made an agreement with the shíshálh (Sechelt) Nation on B.C.’s Sunshine Coast granting management powers, providing for the acquisition of private lands, and making a commitment to recognize Aboriginal title. That agreement was made in August 2024 on the eve of the provincial election but kept hidden for five months. The government eventually posted a copy of it on its website—though with portions redacted. According to an area residents’ association, they were not consulted and weren’t even advised negotiations were taking place.

In the courts, the story is unfolding in a similar way. A judge of the B.C. Supreme Court recently found that the Cowichan First Nation holds Aboriginal title over 800 acres of government land in Richmond, B.C. But that’s not all. Wherever Aboriginal title is found to exist, said the court, it is a “prior and senior right” to fee simple title, whether public or private. That means it trumps the property people have in their house, farm or factory.

If the Cowichan decision holds up on appeal, private property will not be secure anywhere a claim for Aboriginal title is made out. In November, a New Brunswick judge suggested that where such a claim succeeds, the court may instruct the government to expropriate the private property and hand it over to the Aboriginal group.

The Haida Gwaii agreements empower the soft tyranny of legal incoherence. The danger signs are flashing. More of the same is on the way.

Business

Canadians don’t just feel worse off—they actually are

From the Fraser Institute

By Tegan Hill and Grady Munro

A recent survey indicates that the majority of Canadians feel worse off now than in 2020. New data from Statistics Canada show these feelings aren’t unfounded, and that Canadians indeed suffer a worse standard of living than they had in recent years.

According to the survey, 61 per cent of respondents said they are financially worse off than they were before the pandemic, while 89 per cent find it harder to manage expenses on everyday items such as food and shelter. In other words, most Canadians feel they have a lower standard of living than they did in recent years.

The new numbers from Statistics Canada show that inflation-adjusted (GDP)—the final value of all goods and services produced in the economy—shrank by 0.4 per cent during the second quarter of 2025 (i.e. from the beginning of April to the end of June). Population growth was essentially flat during those same three months, meaning inflation-adjusted per-person GDP—a broad measure of individual living standards— declined to $58,855 as of July 2025.

The decline in per-person GDP this quarter may be in part driven by U.S. tariffs, which began taking effect in March. And while Canada previously enjoyed two consecutive quarters of growing per-person GDP at the end of 2024 and beginning of 2025, it’s likely that Canadian businesses and consumers alike shifted spending forwards in order to avoid threatened tariffs. Put simply, per-person GDP growth in previous two quarters may have been fuelled by a shift in spending, which also helped to set up the observed slowdown in economic activity once tariffs began to take effect.

However, Canadian living standards have been stagnant since long before President Trump retook office—indeed, the current standard of living is below the level it was in the middle of 2019 ($59,905) before the pandemic. Moreover, stagnant living standards aren’t a universal problem. For perspective, per-person GDP (adjusted for inflation) in the United States grew by 11.0 per cent from mid-2019 to mid-2025.

Simply put, not only do Canadians feel that they are worse off than in recent years, the data shows they actually are. As such, governments across the country must implement policies that promote economic growth.

Policymakers at all levels of government have discussed the importance of strengthening the economy through various policies, including through removing interprovincial trade barriers and calls for additional tax relief for Canadians. Interprovincial trade barriers inhibit the free flow of goods and services between provinces, and uncompetitively high taxes make Canada less attractive to top talent while also discouraging productive economic behaviour like work, savings, investment and entrepreneurship. Both of these effects act as a drag on the economy, and as such policymakers are correct to highlight these areas.

However, one area that falls under the radar is the growing mountain of government debt in Canada. The persistence of annual budget deficits—where government spends more than it collects in revenues, and must borrow money to make up the difference—in recent years has pushed combined federal and provincial net debt (total debt minus financial assets) to a projected $2.30 trillion as of 2024/25. Despite a growing body of evidence that links higher government debt to slower economic growth (this can happen for many reasons), the federal government along with many provinces plan to continue running deficits and grow the mountain of debt. For perspective, one study found that reducing Canada’s debt to GDP ratio—the size of Canada’s debt relative to the economy—to pre-pandemic levels could boost annual incomes for an average employee by approximately $2,100 (inflation-adjusted). Put simply, governments across the country need to lower spending, balance their budgets, and begin paying down their respective debt burdens.

Not only do Canadians feel they are worse off than they were in recent years, new data shows that living standards actually are worse off. To help turn things around, governments across the country must pursue policies that promote economic growth.

Alberta

Smith government should create stricter rules for Heritage Fund to ensure annual deposits

From the Fraser Institute

By Tegan Hill

Earlier this year, the Smith government released its plan to grow the Heritage Fund—Alberta’s long-term resource revenue (e.g. oil and gas royalties) savings fund—to $250 billion or more by 2050. But due to the government’s own rules, which are easily broken, absent a change in approach, that promise will be hard to keep.

For example, according to the government’s current rules, if it records a budget surplus in any given year, it must use at least 50 per cent of that surplus to repay debt or invest in the Heritage Fund. This commitment, paired with a plan to reinvest any Heritage Fund investment returns back into the fund, is the main way the government plans to build up the fund.

Over the past four years, the Smith government has recorded budget surpluses, fuelled by relatively high resource revenue, and deposited $753 million in the Heritage Fund in 2023 and $2.0 billion in 2024.

But Alberta’s fiscal fortunes have changed. The Smith government now projects budget deficits from 2025/26 to 2027/28. That means that, according to current rules, the government is no longer required to deposit money into the Heritage Fund, even though it’s just as important to continue deposits during times of deficits. And while the government must still reinvest investment returns into the fund during periods of deficits, it could easily break this rule.

That’s the problem with relatively weak rules—they either don’t apply or are ignored when times get tough. Indeed, in 1976/77 when the Lougheed government created the Heritage Fund, it required that 30 per cent of resource revenue be deposited in the fund each year. If the government had stuck to this rule, it could have grown a sizeable Heritage Fund over time. But the 30 per cent contribution rate rule was “statutory,” which meant that the government could unilaterally change the rule when times got tough, and it did.

Following an oil price collapse in 1982/83, the government reduced Heritage Fund contributions to 15 per cent of resource revenue. Following a second oil price collapse in 1986/87, and budget deficits, the government ended resource revenue contributions entirely. Consequently, the government has deposited less than four per cent of Alberta’s total resource revenue in the Heritage Fund over its lifetime. And despite the fund existing for more than 50 years, it’s worth about $25 billion today—a far cry from the Smith government’s $250 billion goal.

Fortunately, there’s a way to ensure Premier Smith’s rules for the fund remain effective over time—make them constitutional, not statutory.

To create constitutional rules, the Alberta government would first seek consent from Albertans through a referendum—a procedure that in itself provides value by educating Albertans on the benefits of stricter rules for the Heritage Fund. Assuming the proposal receives the necessary level of public support, the Alberta government would then pass legislation to recognize the rules and present this legislation to the federal House of Commons and Senate for recognition, resulting in a change pertaining to Alberta in Canada’s Constitution.

As a result, if the Smith government, or any future Alberta government, wanted to reverse the rules or ignore their requirements, it would need to reverse each step in this process—seek approval from Albertans via a referendum, pass provincial legislation, and ask the federal government to approve similar legislation. In other words, it would be much more work to change or ignore Heritage Fund rules—unlike today, when the provincial government can unilaterally change the rules without the approval of Albertans or support from the federal government.

The Smith government has promised to grow the Heritage Fund, which is a worthy objective. But it must stick to its commitment—even when times are tough. Put simply, to grow the Heritage Fund over the long-term, Albertans needs constitutional rules.

-

Censorship Industrial Complex1 day ago

Censorship Industrial Complex1 day agoUK mother imprisoned over tweet says she was ‘political prisoner’ of Keir Starmer

-

C2C Journal1 day ago

C2C Journal1 day agoHow Canada Lost its Way on Freedom of Speech

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoU.S. rejection of climate-alarmed worldview has massive implications for Canada

-

Daily Caller1 day ago

Daily Caller1 day agoTrump Team Floated Energy Incentives With Russia In ‘Sideline’ Ukraine Peace Talks

-

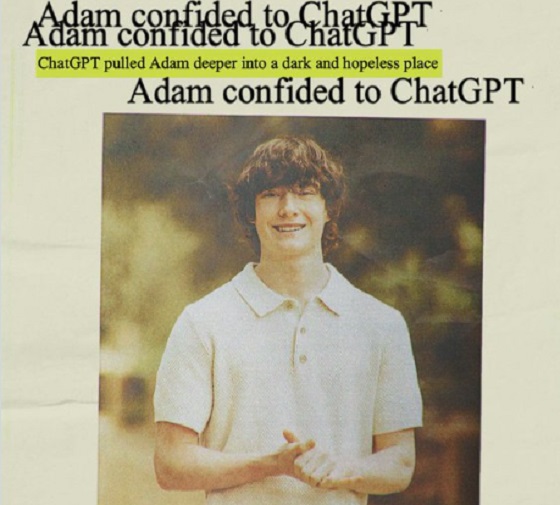

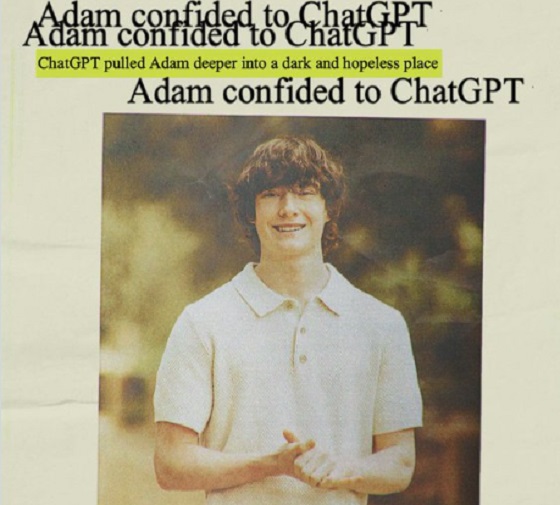

Artificial Intelligence2 days ago

Artificial Intelligence2 days agoParents sue OpenAI, claim ChatGPT acted as teen’s “suicide coach”

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoSmith government should create stricter rules for Heritage Fund to ensure annual deposits

-

Housing1 day ago

Housing1 day agoGovernment, not greed, is behind Canada’s housing problem

-

COVID-192 days ago

COVID-192 days agoNew studies provide ‘irrefutable’ grounds for immediate withdrawal of COVID-19 mRNA shots