Artificial Intelligence

Artificial intelligence is faking it

This article supplied by Troy Media.

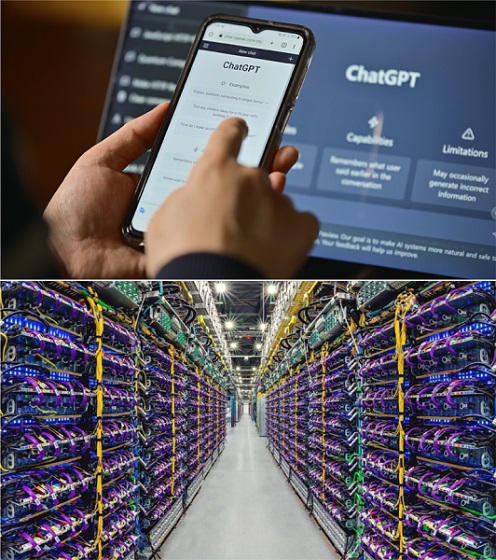

AI chatbots can sound clever, but they don’t understand a word they’re saying

Every time I ask an AI tool a question, I’m struck by how fluent—and how hollow—the answer feels. Noam Chomsky, the MIT linguist and public intellectual, saw this problem long before the rise of ChatGPT: machines can imitate language, but they can’t create meaning.

Chomsky didn’t just dabble in linguistics; he detonated it. His 1957 book Syntactic Structures, a foundational text in modern linguistics, showed that

language isn’t random behaviour but a rule-based system capable of infinite creativity. That insight kick-started the cognitive revolution and laid the

intellectual tracks for the AI train that’s now barreling through our lives. But Chomsky never confused mimicry with meaning. Syntax can be generated. Semantics—what words actually mean—is a human thing.

Most Canadians know Chomsky less as a linguist and more as the political gadfly who’s spent decades skewering U.S. foreign policy and media spin. But before he became a household name for his activism, he was reshaping how we think about language itself. That double role, as scientist and provocateur, makes his critique of artificial intelligence both sharper and harder to dismiss.

That’s what I remind myself as I thumb through the seven AI apps (Perplexity.ai, DeepSeek, Gemini, Claude, Copilot, and, of course, ChatGPT and Google’s Bard) on my phone. They talk back. They help. They screw up. They’re brilliant and idiotic, sometimes in the same breath.

In other words, they’re perfectly imperfect. But unlike people, they fake semantics. They sound meaningful without ever producing meaning.

“Semantics fakers.” Not a Chomsky term, but I’d like to think he’d smirk at it.

Here’s the irony: early AI borrowed heavily from Chomsky’s ideas. His notion that a finite set of rules could generate endless sentences inspired decades of symbolic computing and natural language processing. You’d think, then, he’d be a fan of today’s large language models—the statistical engines behind tools like ChatGPT, Gemini and Claude. Not even close.

Chomsky dismisses them as “statistical messes.” They don’t know language. They don’t know meaning. They can’t tell the difference between possible and impossible sentences. They generate the grammatical alongside the gibberish.

His famous example makes the point: “Colorless green ideas sleep furiously.” A sentence can be syntactically perfect and still utterly meaningless.

That critique lands because we’ve all seen it. These tools can be dazzling one moment and deeply wrong the next. They can pump out grammatical sentences that collapse under the weight of their own emptiness. They’re the digital equivalent of a smooth-talking party guest who never actually answers your question.

The hype isn’t new. AI has been overpromising and underdelivering since the 1960s. Remember the expert systems of the 1980s, which were supposed to replace doctors and lawyers? Or IBM’s Deep Blue in the 1990s, which beat chess champion Garry Kasparov but didn’t get us any closer to actual “thinking” machines? Today’s tools are faster, slicker and more accessible, but they’re still built on the same illusion: that imitation is intelligence.

And while Chomsky has been warning about the limits of language models, others closer to the cutting edge of AI have begun sounding the alarm too.

Canada isn’t a bystander in this story. Geoffrey Hinton, the Toronto-based researcher often called the “godfather of AI,” helped pioneer the deep learning breakthroughs that power today’s chatbots. Yet even he now warns of their dangers: the spread of misinformation through convincing fakes, the loss of jobs on a massive scale, and the risk that advanced systems could slip beyond human control. Pair Hinton’s alarm with Chomsky’s critique, and it’s a sobering reminder that some of the brightest minds behind these tools are telling us not to get carried away.

Chomsky’s point is simple, even if the tech world doesn’t like hearing it: powerful mimicry is not intelligence. These systems show what machines can do with mountains of data and silicon horsepower. But they tell us nothing about what it means to think, to reason, or to create meaning through language.

It all leaves me uneasy. Not terrified—let’s save that for the doomsayers who think the robots are coming for our souls—but uneasy enough to keep my hand on the brake as the hype train speeds up.

That’s why the real conversation we have to have is about what intelligence means—and why AI still isn’t the one having it.

Bill Whitelaw is a director and advisor to many industry boards, including the Canadian Society for Evolving Energy, which he chairs. He speaks and comments frequently on the subjects of social license, innovation and technology, and energy supply networks.

Troy Media empowers Canadian community news outlets by providing independent, insightful analysis and commentary. Our mission is to support local media in helping Canadians stay informed and engaged by delivering reliable content that strengthens community connections and deepens understanding across the country

Artificial Intelligence

Google denies scanning users’ email and attachments with its AI software

From LifeSiteNews

Google claims that multiple media reports are misleading and that nothing has changed with its service.

Tech giant Google is claiming that reports earlier this week released by multiple major media outlets are false and that it is not using emails and attachments to emails for its new Gemini AI software.

Fox News, Breitbart, and other outlets published stories this week instructing readers on how to “stop Google AI from scanning your Gmail.”

“Google shared a new update on Nov. 5, confirming that Gemini Deep Research can now use context from your Gmail, Drive and Chat,” Fox reported. “This allows the AI to pull information from your messages, attachments and stored files to support your research.”

Breitbart likewise said that “Google has quietly started accessing Gmail users’ private emails and attachments to train its AI models, requiring manual opt-out to avoid participation.”

Breitbart pointed to a press release issued by Malwarebytes that said the company made the changed without users knowing.

After the backlash, Google issued a response.

“These reports are misleading – we have not changed anyone’s settings. Gmail Smart Features have existed for many years, and we do not use your Gmail content for training our Gemini AI model. Lastly, we are always transparent and clear if we make changes to our terms of service and policies,” a company spokesman told ZDNET reporter Lance Whitney.

Malwarebytes has since updated its blog post to now say they “contributed to a perfect storm of misunderstanding” in their initial reporting, adding that their claim “doesn’t appear to be” true.

But the blog has also admitted that Google “does scan email content to power its own ‘smart features,’ such as spam filtering, categorization, and writing suggestions. But this is part of how Gmail normally works and isn’t the same as training Google’s generative AI models.”

Google’s explanation will likely not satisfy users who have long been concerned with Big Tech’s surveillance capabilities and its ongoing relationship with intelligence agencies.

“I think the most alarming thing that we saw was the regular organized stream of communication between the FBI, the Department of Homeland Security, and the largest tech companies in the country,” journalist Matt Taibbi told the U.S. Congress in December 2023 during a hearing focused on how Twitter was working hand in glove with the agency to censor users and feed the government information.

If you use Google and would like to turn off your “smart features,” click here to visit the Malwarebytes blog to be guided through the process with images. Otherwise, you can follow these five steps courtesy of Unilad Tech.

- Open Gmail on Desktop and press the cog icon in the top right to open the settings

- Select the ‘Smart Features’ setting in the ‘General’ section

- Turn off the ‘Turn on smart features in Gmail, Chat, and Meet’

- Find the Google Workplace smart features section and opt to manage the smart feature settings

- Switch off ‘Smart features in Google Workspace’ and ‘Smart features in other Google products’

On November 11, a class action lawsuit was filed against Google in the U.S. District Court for the Northern District of California. The case alleges that Google violated the state’s Invasion of Privacy Act by discreetly activating Gemini AI to scan Gmail, Google Chat, and Google Meet messages in October 2025 without notifying users or seeking their consent.

Artificial Intelligence

Trump’s New AI Focused ‘Manhattan Project’ Adds Pressure To Grid

From the Daily Caller News Foundation

Will America’s electricity grid make it through the impending winter of 2025-26 without suffering major blackouts? It’s a legitimate question to ask given the dearth of adequate dispatchable baseload that now exists on a majority of the major regional grids according to a new report from the North American Electric Reliability Corporation (NERC).

In its report, NERC expresses particular concern for the Texas grid operated by the Electric Reliability Council of Texas (ERCOT), where a rapid buildout of new, energy hogging AI datacenters and major industrial users is creating a rapid increase in electricity demand. “Strong load growth from new data centers and other large industrial end users is driving higher winter electricity demand forecasts and contributing to continued risk of supply shortfalls,” NERC notes.

Texas, remember, lost 300 souls in February 2021 when Winter Storm Uri put the state in a deep freeze for a week. The freezing temperatures combined with snowy and icy conditions first caused the state’s wind and solar fleets to fail. When ERCOT implemented rolling blackouts, they denied electricity to some of the state’s natural gas transmission infrastructure, causing it to freeze up, which in turn caused a significant percentage of natural gas power plants to fall offline. Because the state had already shut down so much of its once formidable fleet of coal-fired plants and hasn’t opened a new nuclear plant since the mid-1980s, a disastrous major blackout that lingered for days resulted.

Dear Readers:

As a nonprofit, we are dependent on the generosity of our readers.

Please consider making a small donation of any amount here.

Thank you!

This country’s power generation sector can either get serious about building out the needed new thermal capacity or disaster will inevitably result again, because demand isn’t going to stop rising anytime soon. In fact, the already rapid expansion of the AI datacenter industry is certain to accelerate in the wake of President Trump’s approval on Monday of the Genesis Mission, a plan to create another Manhattan Project-style partnership between the government and private industry focused on AI.

It’s an incredibly complex vision, but what the Genesis Mission boils down to is an effort to build an “integrated AI platform” consisting of all federal scientific datasets to which selected AI development projects will be provided access. The concept is to build what amounts to a national brain to help accelerate U.S. AI development and enable America to remain ahead of China in the global AI arm’s race.

So, every dataset that is currently siloed within DOE, NASA, NSF, Census Bureau, NIH, USDA, FDA, etc. will be melded into a single dataset to try to produce a sort of quantum leap in AI development. Put simply, most AI tools currently exist in a phase of their development in which they function as little more than accelerated, advanced search tools – basically, they’re in the fourth grade of their education path on the way to obtaining their doctorate’s degree. This is an effort to invoke a quantum leap among those selected tools, enabling them to figuratively skip eight grades and become college freshmen.

Here’s how the order signed Monday by President Trump puts it: “The Genesis Mission will dramatically accelerate scientific discovery, strengthen national security, secure energy dominance, enhance workforce productivity, and multiply the return on taxpayer investment into research and development, thereby furthering America’s technological dominance and global strategic leadership.”

It’s an ambitious goal that attempts to exploit some of the same central planning techniques China is able to use to its own advantage.

But here’s the thing: Every element envisioned in the Genesis Mission will require more electricity: Much more, in fact. It’s a brave new world that will place a huge amount of added pressure on power generation companies and grid managers like ERCOT. Americans must hope and pray they’re up to the task. Their track records in this century do not inspire confidence.

David Blackmon is an energy writer and consultant based in Texas. He spent 40 years in the oil and gas business, where he specialized in public policy and communications.

-

Opinion1 day ago

Opinion1 day agoLandmark 2025 Study Says Near-Death Experiences Can’t Be Explained Away

-

Focal Points1 day ago

Focal Points1 day agoSTUDY: TikTok, Instagram, and YouTube Shorts Induce Measurable “Brain Rot”

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoRed Deer’s Jason Stephan calls for citizen-led referendum on late-term abortion ban in Alberta

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoBlacked-Out Democracy: The Stellantis Deal Ottawa Won’t Show Its Own MPs

-

Health2 days ago

Health2 days agoTens of thousands are dying on waiting lists following decades of media reluctance to debate healthcare

-

Agriculture19 hours ago

Agriculture19 hours agoHealth Canada pauses plan to sell unlabeled cloned meat

-

Artificial Intelligence12 hours ago

Artificial Intelligence12 hours agoGoogle denies scanning users’ email and attachments with its AI software

-

Indigenous1 day ago

Indigenous1 day agoIndigenous activist wins landmark court ruling for financial transparency