espionage

Carney Floor Crossing Raises Counterintelligence Questions aimed at China, Former Senior Mountie Argues

Michael Ma has recently attended events with Chinese consulate officials, leaders of a group called CTCCO, and the Toronto “Hongmen,” where diaspora community leaders and Chinese diplomats advocated Beijing’s push to subordinate Taiwan. These same entities have also appeared alongside Canadian politicians at a “Nanjing” memorial in Toronto.

By Garry Clement

Michael Ma’s meeting with consulate-linked officials proves no wrongdoing—but, Garry Clement writes, the timing and optics highlight vulnerabilities Canada still refuses to treat as a security issue.

I spent years in the Royal Canadian Mounted Police learning a simple rule. You assess risk based on capability, intent, and opportunity — not on hope or assumptions. When those three factors align, ignoring them is negligence.

That framework applies directly to Canada’s relationship with the People’s Republic of China — and to recent political events that deserve far more scrutiny than they have received.

Michael Ma’s crossover to the Liberal Party may be completely legitimate, although numerous observers have noted oddities in the timing, messaging, and execution surrounding Ma’s move, which brings Mark Carney within one seat of majority rule.

There is no evidence of wrongdoing.

But from a law enforcement and national security perspective, that is beside the point. Counterintelligence is not about proving guilt after the fact; it is about identifying vulnerabilities before damage is done — and about recognizing when a situation creates avoidable exposure in a known threat environment.

A constellation of ties and public appearances — reported by The Bureau and the National Post — has fueled questions about Ma’s China-facing judgment and vetting. Those reports describe his engagement with a Chinese-Canadian Conservative network that intervened in party leadership politics by urging Erin O’Toole to resign for his “anti-China” stance after 2021 and later calling for Pierre Poilievre’s ouster — while advancing Beijing-aligned framing on key Canada–China disputes.

The National Post has also reported that critics point to Ma’s pro-Beijing community endorsement during his campaign, and his appearance at a Toronto dinner for the Chinese Freemasons — where consular officials used the forum to promote Beijing’s “reunification” agenda for Taiwan. Ma reportedly offered greetings and praised the organization, but did not indicate support for annexation.

Open-source records also show that the same Toronto Chinese Freemasons and leaders Ma has met from a group called CTCCO sponsored and supported Ontario’s “Nanjing Massacre Commemorative Day” initiative (Bill 79) — a campaign celebrated in Chinese state and Party-aligned media, alongside public praise from PRC consular officials in Canada.

China Daily reported in 2018 that the Nanjing memorial was jointly sponsored by CTCCO and the Chinese Freemasons of Canada (Toronto), supported by more than $180,000 in community donations.

Photos show that PRC consular officials and Toronto politicians appeared at related Nanjing memorial ceremonies, including Zhao Wei, the alleged undercover Chinese intelligence agent later expelled from Canada after The Globe and Mail exposed Zhao’s alleged targeting of Conservative MP Michael Chong and his family in Hong Kong.

The fact that Michael Ma recently met with some of the controversial pro-Beijing community figures and organizations described above — including leaders from the Hongmen ecosystem and the CTCCO — does not prove any nefarious intent in either his Conservative candidacy or his decision to cross the floor to Mark Carney.

But it does demonstrate something Ottawa keeps avoiding: the PRC’s influence work is often conducted in plain sight, through community-facing institutions, elite access, and “normal” relationship networks — the very channels that create leverage, deniability, and political pressure over time.

Canada’s intelligence community has been clear.

The Canadian Security Intelligence Service has repeatedly identified the People’s Republic of China as the most active and persistent foreign interference threat facing Canada. These warnings are not abstract. They are rooted in investigations, human intelligence, and allied reporting shared across the Five Eyes intelligence alliance.

At the center of Beijing’s approach is the United Front Work Department — a Chinese Communist Party entity tasked with influencing foreign political systems, cultivating elites, and shaping narratives abroad. In policing terms, it functions as an influence and access network: operating legally where possible, covertly where necessary, and always in service of the Party’s strategic objectives.

What differentiates the People’s Republic of China from most foreign actors is legal compulsion.

Under China’s National Intelligence Law, Chinese citizens and organizations can be compelled to support state intelligence work and to keep that cooperation secret. In practical terms, that creates an inherent vulnerability for democratic societies: coercive leverage — applied through family, travel, business interests, community pressure, and fear.

This does not mean Chinese-Canadians are suspect.

Quite the opposite — many are targets of intimidation themselves. But it does mean the Chinese Communist Party has a mechanism to exert pressure in ways democratic states do not. Ignoring that fact is not tolerance; it is a failure to understand the threat environment.

In the RCMP, we were trained to recognize that foreign interference rarely announces itself. It operates through relationships, access, favors, timing, and silence. It does not require ideological agreement — only opportunity and leverage.

That is why transparency matters. When political figures engage with representatives of an authoritarian state known for interference operations, the burden is not on the public to “prove” concern is justified. The burden is on officials to explain why there is none — and to demonstrate that basic safeguards are in place.

Canada’s allies have already internalized this reality. Australia, the United States, and the United Kingdom have all publicly acknowledged and legislated against People’s Republic of China political interference. Their assessments mirror ours. Their conclusions are the same.

In the United States, the Linda Sun case — covered by The Bureau — illustrates, in the U.S. government’s telling, how United Front–style influence can be both deniable and effective: built through diaspora-facing proxies, insider access, and relationship networks that rarely look like classic espionage until the damage is done.

And this is not a niche concern.

Think tanks in both the United States and Canada — as well as allied research communities in the United Kingdom and Europe — have documented the scale and persistence of these political-influence ecosystems. Nicholas Eftimiades, an associate professor at Penn State and a former senior National Security Agency analyst, has estimated multiple hundreds of such entities are active in the United States. How many operate in Canada is the question Ottawa still refuses to treat with urgency — and, if an upcoming U.S. report is any indication, the answer may be staggering.

Canada’s hesitation to address United Front networks is not due to lack of information. It is due to lack of resolve.

From a law enforcement perspective, this is troubling. You do not wait for a successful compromise before tightening security. You act when the indicators are present — especially when your own intelligence agencies are sounding the alarm.

National security is not ideological. It is practical.

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Business

Canada invests $34 million in Chinese drones now considered to be ‘high security risks’

From LifeSiteNews

Of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police’s fleet of 1,200 drones, 79% pose national security risks due to them being made in China

Canada’s top police force spent millions on now near-useless and compromised security drones, all because they were made in China, a nation firmly controlled by the Communist Chinese Party (CCP) government.

An internal report by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) to Canada’s Senate national security committee revealed that $34 million in taxpayer money was spent on a fleet of 973 Chinese-made drones.

Replacement drones are more than twice the cost of the Chinese-made ones between $31,000 and $35,000 per unit. In total, the RCMP has about 1,228 drones, meaning that 79 percent of its drone fleet poses national security risks due to them being made in China.

The RCMP said that Chinese suppliers are “currently identified as high security risks primarily due to their country of origin, data handling practices, supply chain integrity and potential vulnerability.”

In 2023, the RCMP put out a directive that restricted the use of the made-in-China drones, putting them on duty for “non-sensitive operations” only, however, with added extra steps for “offline data storage and processing.”

The report noted that the “Drones identified as having a high security risk are prohibited from use in emergency response team activities involving sensitive tactics or protected locations, VIP protective policing operations, or border integrity operations or investigations conducted in collaboration with U.S. federal agencies.”

The RCMP earlier this year said it was increasing its use of drones for border security.

Senator Claude Carignan had questioned the RCMP about what kind of precautions it uses in contract procurement.

“Can you reassure us about how national security considerations are taken into account in procurement, especially since tens of billions of dollars have been announced for procurement?” he asked.

“I want to make sure national security considerations are taken into account.”

The use of the drones by Canada’s top police force is puzzling, considering it has previously raised awareness of Communist Chinese interference in Canada.

Indeed, as reported by LifeSiteNews, earlier in the year, an RCMP internal briefing note warned that agents of the CCP are targeting Canadian universities to intimidate them and, in some instances, challenge them on their “political positions.”

The final report from the Foreign Interference Commission concluded that operatives from China may have helped elect a handful of MPs in both the 2019 and 2021 Canadian federal elections. It also concluded that China was the primary foreign interference threat to Canada.

Chinese influence in Canadian politics is unsurprising for many, especially given former Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s past admiration for China’s “basic dictatorship.”

As reported by LifeSiteNews, a Canadian senator appointed by Trudeau told Chinese officials directly that their nation is a “partner, not a rival.”

China has been accused of direct election meddling in Canada, as reported by LifeSiteNews.

As reported by LifeSiteNews, an exposé by investigative journalist Sam Cooper claims there is compelling evidence that Carney and Trudeau are strongly influenced by an “elite network” of foreign actors, including those with ties to China and the World Economic Forum. Despite Carney’s later claims that China poses a threat to Canada, he said in 2016 the Communist Chinese regime’s “perspective” on things is “one of its many strengths.”

espionage

Western Campuses Help Build China’s Digital Dragnet With U.S. Tax Funds, Study Warns

Shared Labs, Shared Harm names MIT, Oxford and McGill among universities working with Beijing-backed AI institutes linked to Uyghur repression and China’s security services.

Over the past five years, some of the world’s most technologically advanced campuses in the United States, Canada and the United Kingdom — including MIT, Oxford and McGill — have relied on taxpayer funding while collaborating with artificial-intelligence labs embedded in Beijing’s security state, including one tied to China’s mass detention of Uyghurs and to the Ministry of Public Security, which has been accused of targeting Chinese dissidents abroad.

That is the core finding of Shared Labs, Shared Harm, a new report from New York–based risk firm Strategy Risks and the Human Rights Foundation. After reviewing tens of thousands of scientific papers and grant records, the authors conclude that Western public funds have repeatedly underwritten joint work between elite universities and two Chinese “state-priority” laboratories whose technologies drive China’s domestic surveillance machinery — an apparatus that, a recent U.S. Congressional threat assessment warns, is increasingly being turned outward against critics in democratic states.

The key Chinese collaborators profiled in the study are closely intertwined with China’s security services. One of the two featured labs is led by a senior scientist from China Electronics Technology Group Corporation (CETC), the sanctioned conglomerate behind the platform used to flag and detain Uyghurs in Xinjiang; the other has hosted “AI + public security” exchanges with the Ministry of Public Security’s Third Research Institute, the bureau responsible for technical surveillance and digital forensics.

The report’s message is blunt: even as governments scramble to stop technology transfer on the hardware side, open academic science has quietly been supplying Chinese security organs with new tools to track bodies, faces and movements at scale.

It lands just as Washington and its allies move to tighten controls on advanced chips and AI exports to China. In the Netherlands’ Nexperia case, the Dutch government invoked a rarely used Cold War–era emergency law this fall to take temporary control of a Chinese-owned chipmaker and block key production from being shifted to China — prompting a furious response from Beijing, and supply shocks that rippled through European automakers.

“The Chinese Communist Party uses security and national security frameworks as tools for control, censorship, and suppressing dissenting views, transforming technical systems into instruments of repression,” the report says. “Western institutions lend credibility, knowledge, and resources to Chinese laboratories supporting the country’s surveillance and defense ecosystem. Without safeguards … publicly funded research will continue to support organizations that contribute to repression in China.”

Cameras and Drones

The Strategy Risks team focuses on two state-backed institutes: Zhejiang Lab, a vast AI and high-performance computing campus founded by the Zhejiang provincial government with Alibaba and Zhejiang University, and the Shanghai Artificial Intelligence Research Institute (SAIRI), now led by a senior CETC scientist. CETC designed the Integrated Joint Operations Platform, or IJOP — the data system that hoovered up phone records, biometric profiles and checkpoint scans to flag “suspicious” people in Xinjiang.

United Nations investigators and several Western governments have concluded that IJOP and related systems supported mass surveillance, detention and forced-labor campaigns against Uyghurs that amount to crimes against humanity.

Against that backdrop, the scale of Western collaboration is striking.

Since 2020, Zhejiang Lab and SAIRI have published more than 11,000 papers; roughly 3,000 of those had foreign co-authors, many from the United States, United Kingdom, and Canada. About 20 universities are identified as core collaborators, including MIT, Stanford, Harvard, Princeton, Carnegie Mellon, Johns Hopkins, UC Berkeley, Oxford, University College London — and Canadian institutions such as McGill University — along with a cluster of leading European technical universities.

Among the major U.S. public funders acknowledged in these joint papers are the National Science Foundation (NSF), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Office of Naval Research (ONR), the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA) and the Department of Transportation. For North America, the warning is twofold: U.S. and Canadian universities are far more entangled with China’s security-linked AI labs than most policymakers grasp — and existing “trusted research” frameworks, built around IP theft, are almost blind to the human-rights risk.

In one flagship example, Zhejiang Lab collaborated with MIT on advanced optical phase-shifting — a field central to high-resolution imaging systems used in satellite surveillance, remote sensing and biometric scanning. The paper cited support from a DARPA program, meaning U.S. defense research dollars effectively underwrote joint work with a Chinese lab that partners closely with military universities and the CETC conglomerate behind Xinjiang’s IJOP system.

Carnegie Mellon projects with Zhejiang Lab focused on multi-object tracking and acknowledged funding from the National Science Foundation and the U.S. Office of Naval Research. Multi-object tracking is a backbone technology for modern surveillance — allowing cameras and drones to follow multiple people or vehicles across crowds and city blocks. “In the Chinese context,” the report notes, such capabilities map naturally onto “public security applications such as protest monitoring,” even when the academic papers present them as neutral advances in computer vision.

The report also highlights Zhejiang Lab’s role as an international partner in CAMERA 2.0, a £13-million U.K. initiative on motion capture, gait recognition and “smart cities” anchored at the University of Bath, and its leadership in BioBit, a synthetic-biology and imaging program whose advisory board includes University College London, McGill University, the University of Glasgow and other Western campuses.

Meanwhile, SAIRI has quietly become a hub for AI that blurs public-security, military and commercial lines.

Established in 2018 and run since 2020 by CETC academician Lu Jun — a designer of China’s KJ-2000 airborne early-warning aircraft and a veteran of command-and-control systems — SAIRI specializes in pose estimation, tracking and large-scale imaging.

Under Lu, the institute has deepened ties with firms already sanctioned by Washington for their roles in Xinjiang surveillance. In 2024 it signed cooperation agreements with voice-recognition giant iFlytek and facial-recognition champion SenseTime, as well as CloudWalk and Intellifusion, which market “smart city” policing platforms.

SAIRI also hosted an “AI + public security” exchange with the Ministry of Public Security’s Third Research Institute — the bureau responsible for technical surveillance and digital forensics — and co-developed what Chinese media billed as the country’s first AI-assisted shooting training system. That platform, nominally built for sports, was overseen by a Shanghai government commission that steers AI into defense and public-security applications, raising the prospect of its use in paramilitary or police training.

Outside the lab, MPS officers have been charged in the United States with running online harassment and intimidation schemes targeting Chinese dissidents, and MPS-linked “overseas police service stations” in North America and Europe have been investigated for pressuring exiles and critics to return to China.

Meanwhile, Radio-Canada, drawing on digital records first disclosed to Australian media in 2024 by an alleged Chinese spy, has reported new evidence suggesting that a Chinese dissident who died in a mysterious kayaking accident near Vancouver was being targeted for elimination by MPS officers and agents embedded in a Chinese conglomerate that the U.S. Treasury accuses of running a money-laundering and modern-slavery empire out of Cambodia.

The new reporting focuses on a former undercover agent for Office No. 1 of China’s Ministry of Public Security — the police ministry at the core of so-called “CCP police stations” in global and Canadian cities, and reportedly tasked with hunting dissidents abroad.

Taken together, cases of alleged Chinese “police station” networks operating globally, new U.S. Congressional reports on worldwide threats from the Chinese Communist Party, and the warnings in Shared Labs, Shared Harm suggest that Western universities are not only helping to build China’s domestic repression apparatus with U.S. taxpayer funds, but may also be contributing to global surveillance tools that can be paired with Beijing’s operatives abroad.

To counter this trend, the paper urges a reset in research governance: broaden due diligence to weigh human-rights risk, mandate transparency over all international co-authorships and joint labs, condition partnerships with security-linked institutions on strict safeguards and narrow scopes of work, and strengthen university ethics bodies so they take responsibility for cross-border collaborations.

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

-

Automotive13 hours ago

Automotive13 hours agoPoliticians should be honest about environmental pros and cons of electric vehicles

-

Agriculture2 days ago

Agriculture2 days agoWhy is Canada paying for dairy ‘losses’ during a boom?

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCanada Hits the Brakes on Population

-

Daily Caller2 days ago

Daily Caller2 days ago‘Almost Sounds Made Up’: Jeffrey Epstein Was Bill Clinton Plus-One At Moroccan King’s Wedding, Per Report

-

Crime2 days ago

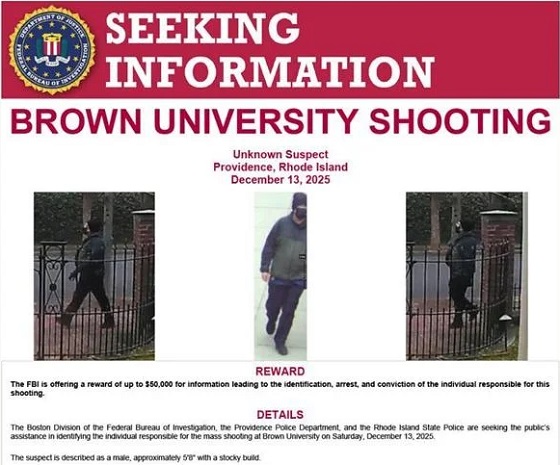

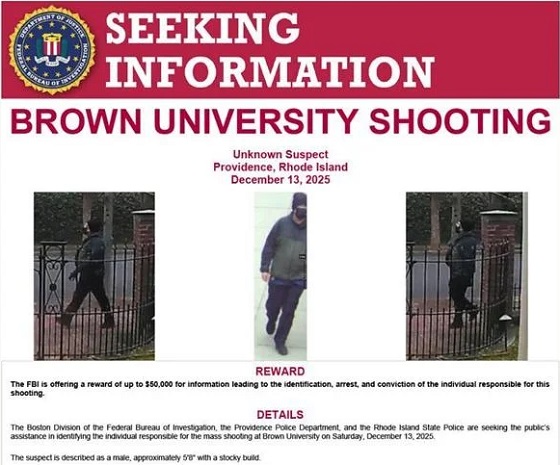

Crime2 days agoBrown University shooter dead of apparent self-inflicted gunshot wound

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoTrump signs order reclassifying marijuana as Schedule III drug

-

Bruce Dowbiggin24 hours ago

Bruce Dowbiggin24 hours agoHunting Poilievre Covers For Upcoming Demographic Collapse After Boomers

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoAlberta’s new diagnostic policy appears to meet standard for Canada Health Act compliance