Business

The promise and peril of Canadian energy corridors

From Resource Works

“Canada is the largest G7 country in terms of landmass, and the smallest in terms of population. We are the only developed country our size physically and economically without a transportation strategy in place”

The concept of national energy corridors does seem straightforward enough, at first glance. It calls to mind a simple right-of-way that slices across Canada, the world’s second-largest landmass, containing pipelines, railways, telecommunications networks, and electricity grids.

Canadians have seen these sorts of physical infrastructure built before, such as the Canadian Pacific Railway during the Confederation era or the more modern Trans-Canada Highway. However, Garrett Kent Fellows will tell you that the true challenge of a national energy corridor is less about the laying of new steel, and more about the careful weaving of institutions to bind the country together.

An Assistant Professor of Economics at the University of Calgary, Fellows is also the Director of Graduate Programs at the School of Public Policy. He is also a Fellow-in-Residence at the prestigious C.D. Howe Institute, where he specializes in competition policy, energy, and infrastructure economics.

Fellows’ curriculum vitae speaks of a scholar whose expertise is routinely sought by politicians, the business community, and thought leaders both in Canada and internationally. He formerly served on Alberta’s Energy Diversification Advisory Committee in 2017, as well as the Economic Corridors Task Force in 2021, and has provided advice to officials from the European Union and the Canadian Senate on economic trade corridors.

At any rate, whenever Fellows has something to say about corridors, people with power and influence listen.

There is a great misunderstanding related to the idea of corridors, which results in an idealized, simplified vision that politicians tend to champion.

“We have a tendency to think about corridors first and foremost as a physical footprint. A right-of-way or area of the country where we are going to put linear infrastructure. That’s not wrong; corridors are that, but they are also an institution,” says Fellows. To him, a national corridor must involve more than simple geography.

A corridor’s success depends upon deep institutional cooperation between all levels of government, First Nations authorities, and the private sector. This is a reality that comes with more challenges than leaders in Ottawa or provincial capitals will care to admit.

Nonetheless, the need for corridors has taken on much greater urgency. The world economy is uncertain, and the threat of trade wars instigated by Donald Trump’s return to the White House has only exacerbated this. Trump’s aggressive tariff policy has revealed the shocking vulnerability of the Canadian economy, which depends on exports.

Fellows is quick to point out that Canada, being massive but sparsely populated, is uniquely exposed as the largest G7 country while having the smallest population and lacking adequate transportation strategies.

“Canada is the largest G7 country in terms of landmass, and the smallest in terms of population. We are the only developed country our size physically and economically without a transportation strategy in place,” Fellows says. This weakness has only strengthened the need for a better-coordinated infrastructure plan that goes beyond simply easing exports, but also increasing Canada’s national economic resilience.

Canada’s history has been marked by impressive infrastructure projects built during periods of hardship, often utilized to boost employment and add to the economic recovery effort. Fellows can see some parallels between the climate of 2025 and the boom in infrastructure construction during the Great Depression.

In the 1930s, projects like the Trans-Canada Highway were developed as part of the federal government’s policy of fiscal stimulus. However, Fellows cautions against simply moving forward with corridor projects as a means of boosting economic security and employment, and says that they are not quick-fix solutions.

“Properly implementing a corridor approach shouldn’t be seen as a shortcut. So it may not be productive to think about this project as shovel-ready.”

Fellows’ concerns are rooted in history, as regulatory uncertainty and rushed processes have contributed to setbacks in the energy sector, such as the cancellation of the Northern Gateway pipeline, the tortured delays on the expansion of the Trans Mountain pipeline, and the death of the Energy East project.

Despite this, the potential of energy corridors remains a compelling and intriguing possibility. Fellows points out that investing in new infrastructure can provide an effective stimulus that remedies stagflationary pressures caused by world trade disputes. “Fiscal stimulus is a natural reaction to stagflation, and a logical one. But we should be thinking about a stimulus that will generate long-term benefits for the country.”

With this approach, stimulus borne of corridors is not just about economic recovery, but also ensuring that it leaves a permanent productive legacy for Canada that helps to secure long-term prosperity instead of temporary relief.

The promise of the corridor also includes the potential of untangling the web of regulations and other complexities that dog new projects. This can be accomplished by improving pre-planning and the environmental assessment process, which can prevent cold feet from investors. Fellows emphasizes that building a better regulatory environment requires cooperation between multiple stakeholders and due diligence.

Fellows is frank about the risk involved, such as stranded capital and white elephants left to rust when market conditions or political priorities change. “As with any infrastructure-based program, there is a risk of stranded capital. We can’t simply take the view that ‘if we build it, they will come.’”

However, he remains firm in his belief that the benefits justify the careful, purposeful efforts required. One of his most interesting insights is that the corridors themselves should not be solely defined as “energy corridors.” Rather, Fellows argues that the model has to bring together diverse infrastructure, telecommunications, transportation, renewable energy transmission, and critical mineral supply chains.

“To maximize the benefits of the corridor approach, we need to be thinking beyond just ‘energy corridors’ and think more broadly about economic corridors.” The rewards of this more holistic vision would lift domestic and international trade and create a foundation for Canada to build a more diversified and resilient economy.

Fellows also hammers home that the idea of corridors lends itself to idealism, but they still demand that people think realistically and be prepared for hard-headed analysis. Corridors are challenging, full of details, bureaucratic, institutional, and diplomatic—hardly an easy task. “Shortcuts make for long delays.”

Being aware of past failures in this regard is important, but Fellows says this makes the difference between accomplishing goals and spouting political rhetoric.

“Realization of any corridor is going to be hard work, but it will be worth it.”

Automotive

Federal government should swiftly axe foolish EV mandate

From the Fraser Institute

Two recent events exemplify the fundamental irrationality that is Canada’s electric vehicle (EV) policy.

First, the Carney government re-committed to Justin Trudeau’s EV transition mandate that by 2035 all (that’s 100 per cent) of new car sales in Canada consist of “zero emission vehicles” including battery EVs, plug-in hybrid EVs and fuel-cell powered vehicles (which are virtually non-existent in today’s market). This policy has been a foolish idea since inception. The mass of car-buyers in Canada showed little desire to buy them in 2022, when the government announced the plan, and they still don’t want them.

Second, President Trump’s “Big Beautiful” budget bill has slashed taxpayer subsidies for buying new and used EVs, ended federal support for EV charging stations, and limited the ability of states to use fuel standards to force EVs onto the sales lot. Of course, Canada should not craft policy to simply match U.S. policy, but in light of policy changes south of the border Canadian policymakers would be wise to give their own EV policies a rethink.

And in this case, a rethink—that is, scrapping Ottawa’s mandate—would only benefit most Canadians. Indeed, most Canadians disapprove of the mandate; most do not want to buy EVs; most can’t afford to buy EVs (which are more expensive than traditional internal combustion vehicles and more expensive to insure and repair); and if they do manage to swing the cost of an EV, most will likely find it difficult to find public charging stations.

Also, consider this. Globally, the mining sector likely lacks the ability to keep up with the supply of metals needed to produce EVs and satisfy government mandates like we have in Canada, potentially further driving up production costs and ultimately sticker prices.

Finally, if you’re worried about losing the climate and environmental benefits of an EV transition, you should, well, not worry that much. The benefits of vehicle electrification for climate/environmental risk reduction have been oversold. In some circumstances EVs can help reduce GHG emissions—in others, they can make them worse. It depends on the fuel used to generate electricity used to charge them. And EVs have environmental negatives of their own—their fancy tires cause a lot of fine particulate pollution, one of the more harmful types of air pollution that can affect our health. And when they burst into flames (which they do with disturbing regularity) they spew toxic metals and plastics into the air with abandon.

So, to sum up in point form. Prime Minister Carney’s government has re-upped its commitment to the Trudeau-era 2035 EV mandate even while Canadians have shown for years that most don’t want to buy them. EVs don’t provide meaningful environmental benefits. They represent the worst of public policy (picking winning or losing technologies in mass markets). They are unjust (tax-robbing people who can’t afford them to subsidize those who can). And taxpayer-funded “investments” in EVs and EV-battery technology will likely be wasted in light of the diminishing U.S. market for Canadian EV tech.

If ever there was a policy so justifiably axed on its failed merits, it’s Ottawa’s EV mandate. Hopefully, the pragmatists we’ve heard much about since Carney’s election victory will acknowledge EV reality.

Business

Prime minister can make good on campaign promise by reforming Canada Health Act

From the Fraser Institute

While running for the job of leading the country, Prime Minister Carney promised to defend the Canada Health Act (CHA) and build a health-care system Canadians can be proud of. Unfortunately, to have any hope of accomplishing the latter promise, he must break the former and reform the CHA.

As long as Ottawa upholds and maintains the CHA in its current form, Canadians will not have a timely, accessible and high-quality universal health-care system they can be proud of.

Consider for a moment the remarkably poor state of health care in Canada today. According to international comparisons of universal health-care systems, Canadians endure some of the lowest access to physicians, medical technologies and hospital beds in the developed world, and wait in queues for health care that routinely rank among the longest in the developed world. This is all happening despite Canadians paying for one of the developed world’s most expensive universal-access health-care systems.

None of this is new. Canada’s poor ranking in the availability of services—despite high spending—reaches back at least two decades. And wait times for health care have nearly tripled since the early 1990s. Back then, in 1993, Canadians could expect to wait 9.3 weeks for medical treatment after GP referral compared to 30 weeks in 2024.

But fortunately, we can find the solutions to our health-care woes in other countries such as Germany, Switzerland, the Netherlands and Australia, which all provide more timely access to quality universal care. Every one of these countries requires patient cost-sharing for physician and hospital services, and allows private competition in the delivery of universally accessible services with money following patients to hospitals and surgical clinics. And all these countries allow private purchases of health care, as this reduces the burden on the publicly-funded system and creates a valuable pressure valve for it.

And this brings us back to the CHA, which contains the federal government’s requirements for provincial policymaking. To receive their full federal cash transfers for health care from Ottawa (totalling nearly $55 billion in 2025/26) provinces must abide by CHA rules and regulations.

And therein lies the rub—the CHA expressly disallows requiring patients to share the cost of treatment while the CHA’s often vaguely defined terms and conditions have been used by federal governments to discourage a larger role for the private sector in the delivery of health-care services.

Clearly, it’s time for Ottawa’s approach to reflect a more contemporary understanding of how to structure a truly world-class universal health-care system.

Prime Minister Carney can begin by learning from the federal government’s own welfare reforms in the 1990s, which reduced federal transfers and allowed provinces more flexibility with policymaking. The resulting period of provincial policy innovation reduced welfare dependency and government spending on social assistance (i.e. savings for taxpayers). When Ottawa stepped back and allowed the provinces to vary policy to their unique circumstances, Canadians got improved outcomes for fewer dollars.

We need that same approach for health care today, and it begins with the federal government reforming the CHA to expressly allow provinces the ability to explore alternate policy approaches, while maintaining the foundational principles of universality.

Next, the Carney government should either hold cash transfers for health care constant (in nominal terms), reduce them or eliminate them entirely with a concordant reduction in federal taxes. By reducing (or eliminating) the pool of cash tied to the strings of the CHA, provinces would have greater freedom to pursue reform policies they consider to be in the best interests of their residents without federal intervention.

After more than four decades of effectively mandating failing health policy, it’s high time to remove ambiguity and minimize uncertainty—and the potential for politically motivated interpretations—in the CHA. If Prime Minister Carney wants Canadians to finally have a world-class health-care system then can be proud of, he should allow the provinces to choose their own set of universal health-care policies. The first step is to fix, rather than defend, the 40-year-old legislation holding the provinces back.

-

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days ago

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days agoEau Canada! Join Us In An Inclusive New National Anthem

-

Crime2 days ago

Crime2 days agoEyebrows Raise as Karoline Leavitt Answers Tough Questions About Epstein

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoCOWBOY UP! Pierre Poilievre Promises to Fight for Oil and Gas, a Stronger Military and the Interests of Western Canada

-

Alberta2 days ago

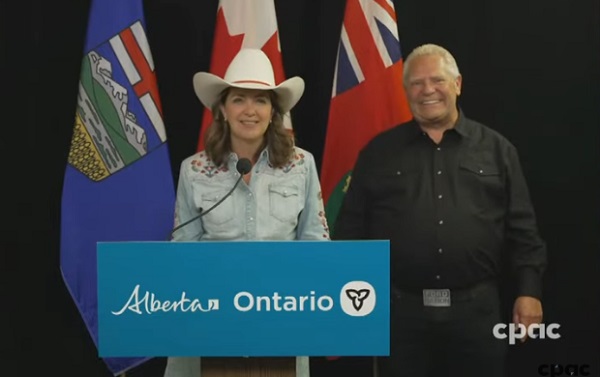

Alberta2 days agoAlberta and Ontario sign agreements to drive oil and gas pipelines, energy corridors, and repeal investment blocking federal policies

-

Crime1 day ago

Crime1 day ago“This is a total fucking disaster”

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoChicago suburb purchases childhood home of Pope Leo XIV

-

Fraser Institute1 day ago

Fraser Institute1 day agoBefore Trudeau average annual immigration was 617,800. Under Trudeau number skyrocketted to 1.4 million annually

-

Daily Caller2 days ago

Daily Caller2 days agoBlackouts Coming If America Continues With Biden-Era Green Frenzy, Trump Admin Warns