Health

MAHA report: Chemicals, screens, and shots—what’s really behind the surge in sick kids

MxM News

MxM News

Quick Hit:

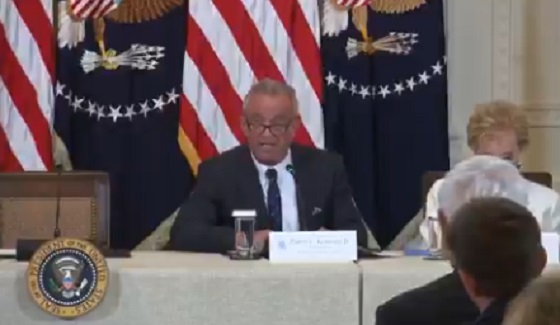

Health Secretary RFK Jr. released a new report Thursday blaming diet, chemicals, inactivity, and overmedication for chronic illnesses now impacting 40% of U.S. children.

Key Details:

-

The Make America Healthy Again (MAHA) Commission report identified four primary culprits: ultra-processed diets, environmental chemicals, sedentary lifestyles, and overreliance on pharmaceuticals.

-

The commission called for renewed scrutiny of vaccine safety, arguing there has been “limited scientific inquiry” into links between immunizations and chronic illness.

-

President Trump called the findings “alarming” and pledged to take on entrenched interests: “We will not be silenced or intimidated by corporate lobbyists or special interests.”

"Our children's bodies are being besieged," says @SecKennedy on the new MAHA Report.

"These root cause factors are at the foundation of what's driving the chronic disease crisis — but until today, the government didn't speak about them." pic.twitter.com/dhF9wEUJGg

— Rapid Response 47 (@RapidResponse47) May 22, 2025

Diving Deeper:

On Thursday, Health and Human Services Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. released a long-anticipated report from the Make America Healthy Again (MAHA) Commission, outlining what the Trump administration sees as the root causes of the chronic disease epidemic among American children. The commission concluded that roughly 40% of U.S. children now suffer from some form of persistent health issue, including obesity, autism, mental health disorders, and autoimmune diseases.

The report identifies four leading contributors: poor nutrition, chemical exposure, lack of physical activity and time outdoors, and overmedicalization of childhood ailments. One of the most alarming statistics cited is the extent to which children’s diets are now composed of what the commission called “ultra-processed foods” (UPFs), with 70% of a typical child’s diet made up of high-calorie, low-nutrient products that contain additives like artificial dyes, sweeteners, preservatives, and engineered fats.

“Whole foods grown and raised by American farmers must be the cornerstone of our children’s healthcare,” the commission urged. It also criticized government-supported programs like school lunches and food stamps for failing to encourage healthy choices, while noting that countries like Italy and Portugal have far lower consumption of UPFs.

The report also raised red flags about widespread chemical exposure through water, air, household items, and personal products. Items of concern included nonstick cookware, pesticides, cleaning supplies, and even fluoride in the water system. The commission referenced research indicating a 50% increase in microplastics found in human brain tissue between 2016 and 2024. It recommended that the U.S. lead in developing AI tools to monitor and mitigate chemical exposure.

Electromagnetic radiation from devices such as phones and laptops was also flagged as a potential contributor to rising disease rates, alongside a marked drop in physical activity among youth. Data cited from the American Heart Association shows 60% of adolescents aged 12-15 do not meet healthy cardiovascular benchmarks, and the majority of children aged 6-17 do not meet federal exercise guidelines.

The commission also tackled what it called a dangerous trend of overmedicating children without considering environmental or lifestyle factors first. Roughly 20% of U.S. children are on at least one prescription medication, including for ADHD, anxiety, and depression.

The commission specifically called out the American Medical Association’s recent stance on curbing health “disinformation,” arguing that it suppresses legitimate inquiry into vaccine safety and efficacy. It further noted that over half of European countries do not mandate vaccinations for school attendance, unlike all 50 U.S. states.

Trump, who established the MAHA Commission by executive order in February, signaled full support for Kennedy’s findings. “In some cases, it won’t be nice or it won’t be pretty, but we have to do it,” he said. “We will not stop until we defeat the chronic disease epidemic in America.”

Policy recommendations based on the report are expected to be delivered to President Trump by August. Among the initial proposals are expanded surveillance of pediatric prescriptions, creation of a national lifestyle trial program, and a new AI-driven system to detect early signs of chronic illness in children.

COVID-19

FDA requires new warning on mRNA COVID shots due to heart damage in young men

From LifeSiteNews

Pfizer and Moderna’s mRNA COVID shots must now include warnings that they cause ‘extremely high risk’ of heart inflammation and irreversible damage in males up to age 24.

The Trump administration’s Food and Drug Administration (FDA) announced it will now require updated safety warnings on mRNA COVID-19 shots to include the “extremely high risk” of myocarditis/pericarditis and the likelihood of long-term, irreversible heart damage for teen boys and young men up to age 24.

The required safety updates apply to Comirnaty, the mRNA COVID shot manufactured by Pfizer Inc., and Spikevax, the mRNA COVID shot manufactured ModernaTX, Inc.

According to a press release, the FDA now requires each of those manufacturers to update the warning about the risks of myocarditis and pericarditis to include information about:

- the estimated unadjusted incidence of myocarditis and/or pericarditis following administration of the 2023-2024 Formula of mRNA COVID-19 shots and

- the results of a study that collected information on cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (cardiac MRI) in people who developed myocarditis after receiving an mRNA COVID-19 injection.

The FDA has also required the manufacturers to describe the new safety information in the adverse reactions section of the prescribing information and in the information for recipients and caregivers.

Additionally, the fact sheets for healthcare providers and for recipients and caregivers for Moderna COVID-19 shot and Pfizer-BioNTech COVID-19 shot, which are authorized for emergency use in individuals 6 months through 11 years of age, have also been updated to include the new safety information in alignment with the Comirnaty and Spikevax prescribing information and information for recipients and caregivers.

In a video published on social media, Dr. Vinay Prasad, director of the Center for Biologics Evaluation & Research Chief Medical and Scientific Officer, explained the alarming reasons for the warning updates.

While heart problems arose in approximately 8 out of 1 million persons ages 6 months to 64 years following reception of the cited shots, that number more than triples to 27 per million for males ages 12 to 24.

Prasad noted that multiple studies have arrived at similar findings.

Business

RFK Jr. says Hep B vaccine is linked to 1,135% higher autism rate

From LifeSiteNews

By Matt Lamb

They got rid of all the older children essentially and just had younger children who were too young to be diagnosed and they stratified that, stratified the data

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found newborn babies who received the Hepatitis B vaccine had 1,135-percent higher autism rates than those who did not or received it later in life, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. told Tucker Carlson recently. However, the CDC practiced “trickery” in its studies on autism so as not to implicate vaccines, Kennedy said.

RFK Jr., who is the current Secretary of Health and Human Services, said the CDC buried the results by manipulating the data. Kennedy has pledged to find the causes of autism, with a particular focus on the role vaccines may play in the rise in rates in the past decades.

The Hepatitis B shot is required by nearly every state in the U.S. for children to attend school, day care, or both. The CDC recommends the jab for all babies at birth, regardless of whether their mother has Hep B, which is easily diagnosable and commonly spread through sexual activity, piercings, and tattoos.

“They kept the study secret and then they manipulated it through five different iterations to try to bury the link and we know how they did it – they got rid of all the older children essentially and just had younger children who were too young to be diagnosed and they stratified that, stratified the data,” Kennedy told Carlson for an episode of the commentator’s podcast. “And they did a lot of other tricks and all of those studies were the subject of those kind of that kind of trickery.”

But now, Kennedy said, the CDC will be conducting real and honest scientific research that follows the highest standards of evidence.

“We’re going to do real science,” Kennedy said. “We’re going to make the databases public for the first time.”

He said the CDC will be compiling records from variety of sources to allow researchers to do better studies on vaccines.

“We’re going to make this data available for independent scientists so everybody can look at it,” the HHS secretary said.

— Matt Lamb (@MattLamb22) July 1, 2025

Health and Human Services also said it has put out grant requests for scientists who want to study the issue further.

Kennedy reiterated that by September there will be some initial insights and further information will come within the next six months.

Carlson asked if the answers would “differ from status quo kind of thinking.”

“I think they will,” Kennedy said. He continued on to say that people “need to stop trusting the experts.”

“We were told at the beginning of COVID ‘don’t look at any data yourself, don’t do any investigation yourself, just trust the experts,”‘ he said.

In a democracy, Kennedy said, we have the “obligation” to “do our own research.”

“That’s the way it should be done,” Kennedy said.

He also reiterated that HHS will return to “gold standard science” and publish the results so everyone can review them.

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoRFK Jr. says Hep B vaccine is linked to 1,135% higher autism rate

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoAlberta Provincial Police – New chief of Independent Agency Police Service

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoWhy it’s time to repeal the oil tanker ban on B.C.’s north coast

-

Energy1 day ago

Energy1 day agoIf Canada Wants to be the World’s Energy Partner, We Need to Act Like It

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoPierre Poilievre – Per Capita, Hardisty, Alberta Is the Most Important Little Town In Canada

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoCBS settles with Trump over doctored 60 Minutes Harris interview

-

Aristotle Foundation1 day ago

Aristotle Foundation1 day agoHow Vimy Ridge Shaped Canada

-

Alberta23 hours ago

Alberta23 hours agoAlberta uncorks new rules for liquor and cannabis