Aristotle Foundation

At Toronto Metropolitan University medical school, some students are more equal than others

READ THE REALITY CHECK

By Bruce Pardy

A new Aristotle Foundation Reality Check from Queen’s University law professor Bruce Pardy details how Canada’s courts reinterpreted even the clear equality clause in the constitution to read in anti-individual “equity.” That hollowed out a founding Canadian principle of equality before the law.

|

|

|

Aristotle Foundation

How Vimy Ridge Shaped Canada

The Battle of Vimy Ridge was a unifying moment for Canada, then a young country. The Aristotle Foundation’s Danny Randell explains what happened at Vimy in 1917, and why it still matters to Canada today.

About the Aristotle Foundation

The Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy is a new think tank that aims to renew civil, common-sense discourse in Canada. As an educational charity, we publish books, videos, fact sheets, studies, columns, interviews, and infographics.

Visit our website at www.aristotlefoundation.org for more of our content.

Aristotle Foundation

The Canadian Medical Association’s inexplicable stance on pediatric gender medicine

By Dr. J. Edward Les

The thalidomide saga is particularly instructive: Canada was the last developed country to pull thalidomide from its shelves — three months during which babies continued to be born in this country with absent or deformed limbs

Physicians have a duty to put forward the best possible evidence, not ideology, based treatments

Late last month, the Canadian Medical Association (CMA) announced that it, along with three Alberta doctors, had filed a constitutional challenge to Alberta’s Bill 26 “to protect the relationship between patients, their families and doctors when it comes to making treatment decisions.”

Bill 26, which became law last December, prohibits doctors in the province from prescribing puberty blockers and hormone therapies for those under 16; it also bans doctors from performing gender-reassignment surgeries on minors (those under 18).

The unprecedented CMA action follows its strongly worded response in February 2024 to Alberta’s (at the time) proposed legislation:

“The CMA is deeply concerned about any government proposal that restricts access to evidence-based medical care, including the Alberta government’s proposed restrictions on gender-affirming treatments for pediatric transgender patients.”

But here’s the problem with that statement, and with the CMA’s position: the evidence supporting the “gender affirmation” model of care — which propels minors onto puberty blockers, cross-gender hormones, and in some cases, surgery — is essentially non-existent. That’s why the United Kingdom’s Conservative government, in the aftermath of the exhaustive four-year-long Cass Review, which laid bare the lack of evidence for that model, and which shone a light on the deeply troubling potential for the model’s irreversible harm to youth, initiated a temporary ban on puberty blockers — a ban made permanent last December by the subsequent Labour government. And that’s why other European jurisdictions like Finland and Sweden, after reviews of gender affirming care practices in their countries, have similarly slammed the brakes on the administration of puberty blockers and cross-gender hormones to minors.

It’s not only the Europeans who have raised concerns. The alarm bells are ringing loudly within our own borders: earlier this year, a group at McMaster University, headed by none other than Dr. Gordon Guyatt, one of the founding gurus of the “evidence-based care” construct that rightfully underpins modern medical practice, issued a pair of exhaustive systematic reviews and meta analyses that cast grave doubts on the wisdom of prescribing these drugs to youth.

And yet, the CMA purports to be “deeply concerned about any government proposal that restricts access to evidence-based medical care,” which begs the obvious question: Where, exactly, is the evidence for the benefits of the “gender affirming” model of care? The answer is that it’s scant at best. Worse, the evidence that does exist, points, on balance, to infliction of harm, rather than provision of benefit.

CMA President Joss Reimer, in the group’s announcement of the organization’s legal action, said:

“Medicine is a calling. Doctors pursue it because they are compelled to care for and promote the well-being of patients. When a government bans specific treatments, it interferes with a doctor’s ability to empower patients to choose the best care possible.”

Indeed, we physicians have a sacred duty to pursue the well-being of our patients. But that means that we should be putting forward the best possible treatments based on actual evidence.

When Dr. Reimer states that a government that bans specific treatments is interfering with medical care, she displays a woeful ignorance of medical history. Because doctors don’t always get things right: look to the sad narratives of frontal lobotomies, the oxycontin crisis, thalidomide, to name a few.

The thalidomide saga is particularly instructive: it illustrates what happens when a government drags its heels on necessary action. Canada was the last developed country to pull thalidomide, given to pregnant women for morning sickness, from its shelves, three months after it had been banned everywhere else — three months during which babies continued to be born in this country with absent or deformed limbs, along with other severe anomalies. It’s a shameful chapter in our medical past, but it pales in comparison to the astonishing intransigence our medical leaders have displayed — and continue to display — on the youth gender care file.

A final note (prompted by thalidomide’s history), to speak to a significant quibble I have with Alberta’s Bill 26 legislation: as much as I admire Premier Danielle Smith’s courage in bringing it forward, the law contains a loophole allowing minors already on puberty blockers and cross-gender hormones to continue to take them. Imagine if, after it was removed from the shelves in 1962, government had allowed pregnant women already on the drug to continue to take thalidomide. Would that have made any sense? Of course not. And the same applies to puberty blockers and cross-gender hormones: they should be banned outright for all youth.

That argument is the kind our medical associations should be making — and would be making, if they weren’t so firmly in the grasp, seemingly, of ideologues who have abandoned evidence-based medical care for our youth.

J. Edward Les is a Calgary pediatrician, a senior fellow with the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy, and co-author of “Teenagers, Children, and Gender Transition Policy: A Comparison of Transgender Medical Policy for Minors in Canada, the United States, and Europe.”

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoOttawa Funded the China Ferry Deal—Then Pretended to Oppose It

-

COVID-192 days ago

COVID-192 days agoNew Peer-Reviewed Study Affirms COVID Vaccines Reduce Fertility

-

MAiD2 days ago

MAiD2 days agoCanada’s euthanasia regime is not health care, but a death machine for the unwanted

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoWorld Economic Forum Aims to Repair Relations with Schwab

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoThe permanent CO2 storage site at the end of the Alberta Carbon Trunk Line is just getting started

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoAlberta’s government is investing $5 million to help launch the world’s first direct air capture centre at Innisfail

-

Business2 days ago

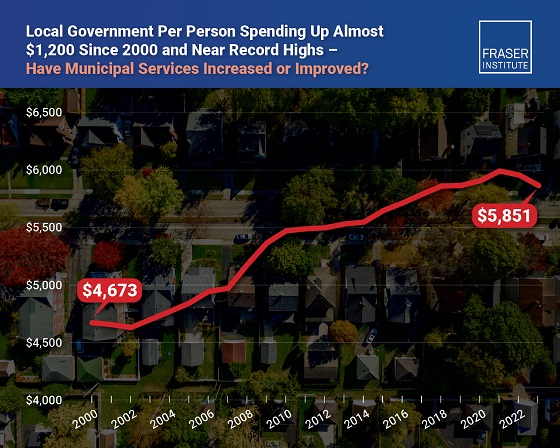

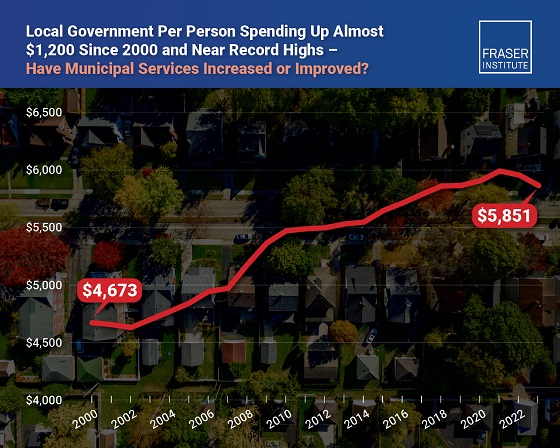

Business2 days agoMunicipal government per-person spending in Canada hit near record levels

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoA new federal bureaucracy will not deliver the affordable housing Canadians need