Fraser Institute

Endless spending increases will not fix Canada’s health-care system

From the Fraser Institute

By Mackenzie Moir and Jake Fuss

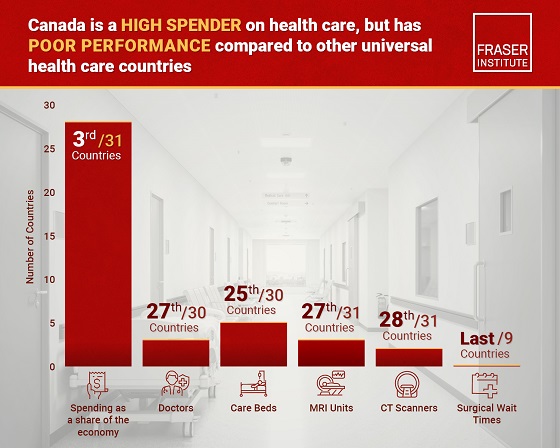

Canada’s health-care system ranked as the most expensive (as a share of the economy) among 30 universal health-care countries. And despite these relatively high levels of spending, Canada continues to lag behind its peers on key indicators of performance.

In February 2023, the federal government announced the money they send to the provinces for health care would increase, yet again. Despite being billed as a fix for health care, these spending increases will not actually provide any relief for Canadian patients.

The Canada Health Transfer (CHT), the main federal financial tool for funding provincial health care, has increased from $34.0 billion in 2015/16 to $52.1 billion this year (2024/25), a 53.1 per cent increase in about a decade. Moreover, the federal government has committed to increases in the transfer at a guaranteed 5 per cent until 2027/28.

This latest increase in the CHT, however, is only one part of the $46.2 billion in new money being doled out over the next 10 years. More than half (roughly $25 billion) is currently being given to provinces who’ve signed up to work towards a number of “shared priorities” with Ottawa, such as mental health and substance abuse.

Clearly, the federal government has decided to substantially increase health-care spending in more than one way. But will it produce results?

These periodic “fixes” occasionally championed by Ottawa every few years are nothing new. And unfortunately, the data show that longstanding problems, including long waits for medical care and doctor shortages, will persist even though Canada is certainly no slouch when compared to its peers on health-care spending.

A recent study found that, when adjusted for differences in age (because older populations tend to spend more on health care), Canada’s health-care system ranked as the most expensive (as a share of the economy) among 30 universal health-care countries. And despite these relatively high levels of spending, Canada continues to lag behind its peers on key indicators of performance.

For example, Canada had some of the fewest physicians (ranked 28th of 30 countries), hospital beds (ranked 23rd of 29) and diagnostic technology such as MRIs (ranking 25th of 29 countries) and CT scanners (ranking 26th out of 30 countries) compared to other high-income countries with universal health care.

It also ranked at or near the bottom on measures such as same-day medical appointments, how easy it is to find afterhours care, and the timeliness of specialist appointments and surgical care.

And wait times have been getting worse. Just last year Canada recorded the longest ever delay for non-emergency care at 27.7 weeks, a 198 per cent increase from the 9.3 week wait experienced in 1993 (the first year national estimates were published).

But it’s not just the health-care system that’s in shambles, despite our high spending. Our federal finances are, too. Years of substantial increases in federal spending have strained the country’s finances. The Trudeau government’s latest budget projects a deficit of $39.8 billion this year, with more spent on debt interest ($54.1 billion) than on what the federal government gives to the provinces for health care.

Again, these periodic injections of federal funds to the provinces to supposedly fix health care are nothing new. Ottawa has relied on this strategy in the past and wait times have grown longer over the last three decades. Endless increases in spending will not fix our health-care system.

Authors:

Energy

National media energy attacks: Bureau chiefs or three major Canadian newspapers woefully misinformed about pipelines

From the Fraser Institute

These three allegedly well informed national opinion-shapers are incredibly ignorant of national energy realities.

In a recent episode of CPAC PrimeTime Politics, three bureau chiefs from three major Canadian newspapers discussed the fracas between Alberta Premier Danielle Smith and Prime Minister Mark Carney. The Smith government plans to submit a proposal to Ottawa to build an oil pipeline from Alberta to British Columbia’s north coast. The episode underscored the profound disconnect between these major journalistic gatekeepers and the realities of energy policy in Canada.

First out of the gate, the Globe and Mail’s Robert Fife made the (false) argument that we already have the Trans Mountain pipeline expansion (TMX), which is only running at 70 per cent, so we don’t need additional pipelines. This variant of the “no market case” argument misunderstands both the economics of running pipelines and the reality of how much oilsands production can increase to supply foreign markets if—and only if—there’s a way to get it there.

In reality, since the TMX expansion entered service, about 80 per cent of the system’s capacity is reserved for long-term contracts by committed shippers, and the rest is available on a monthly basis for spot shippers who pay higher rates due largely to government-imposed costs of construction. From June 2024 to June 2025, committed capacity was fully utilized each month, averaging 99 per cent utilization. Simply put, TMX is essentially fully subscribed and flowing at a high percentage of its physical capacity.

And the idea that we don’t need additional capacity is also silly. According to S&P Global, Canadian oilsands production will reach a record annual average production of 3.5 million barrels per day (b/d), and by 2030 could top 3.9 million b/d (that’s 500,000 b/d higher than 2024). Without pipeline expansion, this growth may not happen. Alberta’s government, which is already coordinating with pipeline companies such as Enbridge, hopes to see oilsands production double in coming years.

Next, Mia Rabson, Ottawa deputy bureau chief of the Canadian Press, implied that Smith’s proposal is not viable because it comes from government, not the private sector. But Rabson neglected to say that it would be foolish for any company to prepare a very expensive project proposal in light of current massive regulatory legislative barriers (tanker ban off B.C. coast, oil and gas emission cap, etc.). Indeed, proposal costs can run into the billions.

Finally, Joel-Denis Bellavance, Ottawa bureau chief of La Presse, opined that a year ago “building a pipeline was not part of the national conversation.” Really? On what planet? How thick is the bubble around Quebec? Is it like bulletproof Perspex? This is a person helping shape Quebec opinion on pipelines in Western Canada, and if we take him at his word, he doesn’t know that pipelines and energy infrastructure have been on the agenda for quite some time now.

If these are the gatekeepers of Canadian news in central Canada, it’s no wonder that the citizenry seems so woefully uninformed about the need to build new pipelines, to move Alberta oil and gas to foreign markets beyond the United States, to strengthen Canada’s economy and to employ in many provinces people who don’t work in the media.

Business

Canada has fewer doctors, hospital beds, MRI machines—and longer wait times—than most other countries with universal health care

From the Fraser Institute

Despite a relatively high level of spending, Canada has significantly fewer doctors, hospital beds, MRI machines and CT scanners compared to other countries with universal health care, finds a new study released today by the Fraser Institute, an independent, non-partisan Canadian public policy think-tank.

“There’s a clear imbalance between the high cost of Canada’s health-care system and the actual care Canadians receive in return,” said Mackenzie Moir, senior policy

analyst at the Fraser Institute and author of Comparing Performance of Universal Health-Care Countries, 2025.

In 2023, the latest year of available comparable data, Canada spent more on health care (as a percentage of the economy/GDP, after adjusting for population age) than

most other high-income countries with universal health care (ranking 3rd out of 31 countries, which include the United Kingdom, Australia and the Netherlands).

And yet, Canada ranked 27th (of 30 countries) for the availability of doctors and 25th (of 30) for the availability of hospital beds.

In 2022, the latest year of diagnostic technology data, Canada ranked 27th (of 31 countries) for the availability of MRI machines and 28th (of 31) for CT scanners.

And in 2023, among the nine countries with universal health-care systems included in the Commonwealth Fund’s International Health Policy Survey, Canada ranked last for the percentage of patients able to make same- or next-day appointments when sick (22 per cent) and had the highest percentage of patients (58 per cent) who waited two months or more for non-emergency surgery. For comparison, the Netherlands had much higher rates of same- or next-day appointments (47 per cent) and much lower waits of two months or more for non-emergency surgery (20 per cent).

“To improve health care for Canadians, our policymakers should learn from other countries around the world with higher-performing universal health-care systems,”

said Nadeem Esmail, director of health policy at the Fraser Institute.

Comparing Performance of Universal Health Care Countries, 2025

- Of the 31 high-income universal health-care countries, Canada ranks among the highest spenders, but ranks poorly on both the availability of most resources and access to services.

- After adjustments for differences in the age of the population of these 31 countries, Canada ranked third highest for spending as a percentage of GDP in 2023 (the most recent year of comparable data).

- Across 13 indictors measured, the availability of medical resources and timely access to medical services in Canada was generally below that of the average OECD country.

- In 2023, Canada ranked 27th (of 30) for the relative availability of doctors and 25th (of 30) for hospital beds dedicated to physical care. In 2022, Canada ranked 27th (of 31) for the relative availability of Magnetic Resonance Im-aging (MRI) machines, and 28th (of 31) for CT scanners.

- Canada ranked last (or close to last) on three of four indicators of timeliness of care.

- Notably, among the nine countries for which comparable wait times measures are available, Canada ranked last for the percentage of patients reporting they were able to make a same- or next-day appointment when sick (22%).

- Canada also ranked eighth worst for the percentage of patients who waited more than one month to see a specialist (65%), and reported the highest percentage of patients (58%) who waited two months or more for non-emergency surgery.

- Clearly, there is an imbalance between what Canadians get in exchange for the money they spend on their health-care system.

Mackenzie Moir

Senior Policy Analyst, Fraser Institute

-

Agriculture14 hours ago

Agriculture14 hours agoFrom Underdog to Top Broodmare

-

Carbon Tax2 days ago

Carbon Tax2 days agoBack Door Carbon Tax: Goal Of Climate Lawfare Movement To Drive Up Price Of Energy

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoTrump, Putin meeting in Hungary called off

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoCalgary’s High Property Taxes Run Counter to the ‘Alberta Advantage’

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoAlberta’s licence plate vote is down to four

-

Bruce Dowbiggin1 day ago

Bruce Dowbiggin1 day agoIs The Latest Tiger Woods’ Injury Also A Death Knell For PGA Champions Golf?

-

City of Red Deer24 hours ago

City of Red Deer24 hours agoCindy Jefferies is Mayor. Tristin Brisbois, Cassandra Curtis, Jaelene Tweedle, and Adam Goodwin new Councillors – 2025 Red Deer General Election Results

-

Digital ID2 days ago

Digital ID2 days agoThousands protest UK government’s plans to introduce mandatory digital IDs