Opinion

Why Everything We Thought About Drugs Was Wrong

Michael Schellenberger is a leading environmentalist and progressive activist who has become disillusioned with the movements he used to help lead.

His passion for the environment and progressive issues remains, but his approach is unique and valuable.

Michael Shellenberger is author of the best-selling “Apocalypse Never”

This newsletter was sent out to Michael Schellenberger’s subscribers on Substack

The road to hell was paved with victimology

In the late 1990s and early 2000s, I worked with a group of friends and colleagues to advocate drug decriminalization, harm reduction, and criminal justice reform. I helped progressive Congressperson Maxine Waters organize civil rights leaders to advocate for needle exchange so that heroin users wouldn’t get HIV-AIDS. I fought for the treatment of drug addiction as a public health problem not a criminal justice one. And we demanded that housing be given to the homeless without regard for their own struggles with drugs.

Our intentions were good. We thought it was irrational to criminalize the distribution of clean needles to drug users when doing so had proven to save lives. We were upset about mass incarceration, particularly of African Americans and Latinos, for nonviolent drug offenses. And we believed that the approach European nations like the Netherlands and Portugal had taken to decriminalize drugs, and expand drug treatment, was the right one.

But it’s obvious now that we were wrong. Over the last 20 years the U.S. liberalized drug laws. During that time, deaths from illicit drugs rose from 17,000 to 93,000. Three three times more people die from illicit drug use than from car accidents; five times more die from drugs than homicide. Many of those people are homeless and die alone in the hotel rooms and apartment units given away as part of the harm reduction-based “Housing First” approach to homelessness. Others are children found dead by their parents on the floors of their rooms.

Many progressives today say the problem is that we didn’t go far enough, and to some extent they are right. A big factor behind rising drug deaths has been the contamination of cocaine, heroin, and counterfeit prescription opioids with fentanyl. Others say that concerns over rising drug deaths are misplaced, and that alcohol and tobacco kill more people than illicit drugs.

But drug deaths were rising in the U.S. long before the arrival of fentanyl, and most of the people who die from tobacco and alcohol do so in old age, not instantly, like they do when they are poisoned or overdose. Of the nearly 90,000 people in the U.S. who die of alcohol-related causes annually, just 2,200 die immediately from acute alcohol poisoning.

What about mass incarceration? It’s true that nearly half of the people in federal prisons are there for nonviolent drug offenses. But there are eight times more people in state prisons than federal prisons, and just 14 percent of people in state prisons are there for nonviolent drug offenses and just 4 percent for nonviolent possession. Half of state prisoners are there for murder, rape, robbery and other violent offenses.

While it’s true that both Netherlands and Portugal reduced criminal penalties, both nations still ban drug dealing, arrest drug users, and sentence dealers and users to prison or rehabilitation. “If somebody in Portugal started injecting heroin in public,” I asked the head of drug policy in that country, “what would happen to them?” He said, without hesitation, “They would be arrested.”

And being arrested is sometimes what addicts need. “I am a big fan of mandated stuff,” said Victoria Westbrook. “I don’t recommend it as a way to get your life together, but getting indicted by the Feds worked for me. I wouldn’t have done this without them.” Today Victoria is working for the San Francisco city government to integrate ex-convicts back into society.

But people in progressive cities are today shouted down for even suggesting a role for law enforcement. “Anytime a person says, ‘Maybe the police and the health care system could work together?’ or, ‘Maybe we could try some probation or low-level arrests,’ there’s an enormous outcry,” said Stanford addiction specialist Keith Humphreys. “‘No! That’s the war on drugs! The police have no role in this! Let’s open up some more services and people will come in and use them voluntarily!’”

Why is that? Why, in the midst of the worst drug death crisis in world history, and the examples of Portugal and Netherlands, are progressives still opposed to shutting down the street fentanyl markets in places like San Francisco that are killing people?

We Care A Lot

The City of San Francisco opened this homeless encampment virtually on the front steps of city hall.

There are many financial interests that make money from the drug crisis and so it’s reasonable to ask whether progressive inaction stems from political donations from addiction, homelessness, and service providers. California spends more on mental health than any other state but saw its homeless population rise 31 percent even as it declined 18 percent in the rest of the U.S. San Francisco spends significantly more on cash welfare and housing for the homeless than other cities but has one of the worst homeless and drug death crises, per capita.

But we progressives who fought to change drug laws and attitudes were not primarily motivated by money. Sure, we needed George Soros and other wealthy individuals to support our work. But we could have made more money doing other things, and Soros and others have nothing to gain financially from drug decriminalization. The same goes for homelessness. The most influential Housing First advocates work in non-profits and universities.

Is it because so many progressives who fought for decriminalization themselves used drugs? Everybody I knew in that period, myself included, smoked marijuana, drank alcohol, and experimented with psychedelics and occasionally with harder drugs. Several of the donors who supported our work were known to smoke marijuana.

But I saw no evidence that advocates for drug decriminalization and harm reduction used illicit drugs at a higher rate than the rest of the population. Some used them less and showed far greater awareness of the harms of drugs, including addiction, than many other people I have met, likely due to their higher socio-economic status as much as their specific knowledge of the issue.

And the core motivation of the people I worked with was ideological. Many people, including many progressives, were libertarian, and fundamentally believed the government did not have a right to tell able-bodied adults what drugs they could and could not use. But many more, myself included, were upset by mass incarceration, and the ways in which incarceration destroys families, disproportionately African American and Latino ones.

Our views were too simplistic and wrong. Many things undermine families and communities, of all colors, well before anyone is incarcerated, including drugs and the crime and violence associated with them. And, violent communities attract the drug trade more than the drug trade makes communities violent, both scholars and journalists find.

But mostly we were too emotional. Progressives hold two moral values particularly deeply: caring and fairness. “Across many scales, surveys, and political controversies,” notes the psychologist Jonathan Haidt, “liberals turn out to be more disturbed by signs of violence and suffering, compared to conservatives, and especially to libertarians.”

The problem is that, in the process of valuing care so much, progressives abandon other important values, argue Haidt and other researchers in a field called Moral Foundations Theory. While progressives (“liberal” and “very liberal” people) hold the values of Caring, Fairness, and Liberty, they tend to reject the values of Sanctity, Authority, and Loyalty as wrong. Because these values are so deeply held, often subconsciously, Moral Foundations Theory explains well why so many progressives and conservatives today view each other as not merely uninformed but immoral.

The Victim God

California Governor Gavin Newsome has proposed a 12 Billion dollar plan to build homes for California’s entire homeless population.

The values of Sanctity and Authority appear to explain why conservatives and moderate Democrats more than progressives favor prohibitions on things like sleeping on sidewalks, public use of hard drugs, and other behaviors. In a more traditional morality, drug use is seen as violating the Sanctity of the body, and the importance of self-control. Sleeping on sidewalks is seen as violating the value of Authority of laws and thus Loyalty to America. Writes Haidt, “liberals are often willing to trade away fairness when it conflicts with compassion or their desire to fight oppression.”

But there is a twist. Progressives don’t trade away Fairness for victims, only for those they see as privileged. Progressives still value Fairness, but more for victims, and their progressive allies, than for everyone equally, and particularly not for people progressives view as the oppressors and victimizers.

Conservatives and moderates tend to define Fairness around equal treatment, including enforcement of the law. They tend to believe we should enforce the law against the homeless man who is sleeping and urinating on BART, our subway system, even if he is a victim. Progressives disagree. They demand we take into account that the man is a victim in deciding whether to arrest and how to sentence whole classes of people including the homeless, mentally ill, and addicts.

Progressives also value Liberty, or freedom, differently from conservatives. Many progressives reject the value of Liberty for Big Tobacco and cigarette smokers but embrace the value of Liberty for fentanyl dealers and users. Why? Because progressives view fentanyl dealers and users, who are disproportionately poor, sick, and nonwhite, as victims of a bad system.

Progressives also value Authority and Loyalty for victims above everyone else. San Francisco homelessness advocate Jennifer Friedenbach told me that we should “center unhoused people, primarily black and brown folks, that are experiencing homelessness, folks with disabilities. They’re the voices that should be centered.” She is not rejecting Authority or Loyalty. Rather, she is suggesting that we should have Loyalty to the victims, and that they, not governments, should have Authority.

Indeed, progressives insist on taking orders, supposedly without questioning them, from the homeless themselves. “Drug use is often the only thing that feels good for them, to oversimplify it,” said Kristen Marshall, who oversees San Francisco’s response to drug overdoses. “When you understand that, you stop caring about the drug use and ask people what they need.”

The San Francisco Coalition on Homelessness has similarly argued that the city must let homeless people sit and lie on sidewalks, and camp in public spaces including parks and sidewalks, if that’s what they would prefer, rather than require them to stay in shelters. Once you decide, in advance, to let victims determine their fates, then much else can be justified.

Many progressives do something similar with Sanctity, which is to value some things as sacred or pure. Monique Tula, the head of the Harm Reduction Coalition, argues for “bodily autonomy” against mandatory drug treatment for people who break the law to support their addiction. In so doing, she is insisting upon the Sanctity of the body, not rejecting it. The difference between her definition of Sanctity and the traditional view of Sanctity was what violated it. Where traditional morality views recreational injection drug use as a violation of the Sanctity of the body, Tula, like many libertarians, believes that the state coercing sobriety is.

All religions and moralities have light and dark sides, suggests Haidt. “Morality binds and blinds,” he writes. On the one hand, they bind us together in groups and societies, helping us realize our individual and social needs, and are thus very positive. But religions and moralities can also create giant blind spots preventing us from seeing our dark sides, and thus can be very negative.

Victimology takes the truth that it is wrong for people to be victimized and distorts it by going a step further. Victimology asserts that victims are inherently good because they have been victimized. It robs victims of their moral agency and creates double standards that frustrate any attempt to criticize their behavior, even if they’re behaving in self-destructive, antisocial ways like smoking fentanyl and living in a tent on the sidewalk. Such reasoning is obviously faulty. It purifies victims of all badness. But by appealing to emotion, victimology overrides reason and logic.

Victimology appears to be rising as traditional religions are declining. Unlike traditional religions, many nontraditional religions are largely invisible to the people who hold them most strongly. A secular religion like victimology is powerful because it meets the contemporary psychological, social, and spiritual needs of its believers, but also because it appears obvious, not ideological, to them. Advocates of “centering” victims, giving them special rights, and allowing them to behave in ways that undermine city life, don’t believe, in my experience, that they are adherents to a new religion, but rather that they are more compassionate and more moral than those who hold more traditional views.

A Bad Case of San Fransickness

Case workers at San Francisco City Hall Homeless Encampment

“Safe Sleeping Sites” is the name San Francisco gives to parking lots of tents of homeless addicts shooting and smoking fentanyl and meth. They are expensive, costing the city $60,000 per tent to maintain. Some people say they look like a natural disaster, but with city-funded social workers providing services to the people in tents, they look to me more like a medical experiment, albeit one that no board of ethics would ever permit.

At the Sites the city isn’t providing drug treatment; it’s providing easy access to drugs. That includes cash in the form of welfare payments with which to purchase drugs, and the equipment with which to inject them. As such, progressives cities like San Francisco are directly financing the drug death crisis.

Is this Munchausen syndrome by proxy, which is when a parent deliberately makes their child sick so they can feel important? In San Fransicko, I consider this possibility, and ultimately conclude that while the progressive approach to drug addiction and homelessness can be fairly described as pathological altruism, it would be unfair to call it sadistic. Many of the drug-addicted and mentally ill homeless are, in fact, sick, and most progressives have good intentions.

But it is not unfair to point out that the city’s approach of playing the Rescuer is resulting in worsening addiction and rising drug deaths. Nor is it unfair to point out that we limit people’s potential for freedom by labeling them Victims and “centering” their trauma, rather than viewing victimization as an opportunity for heroism. Nor is it unfair to point out, as I have attempted to do by describing the history, that San Francisco’s political, business, and cultural leaders should all know better by now.

People suffering from addiction and living on the street are ill. To mix them up in speech and policy with people who are merely poor is deceptive. Leading scholars have for thirty years denounced the conflation of the merely poor with disaffiliated addicts. Yet progressive advocates for the homeless continue to engage in the same sleight of hand by using the single term “homeless,” tricking journalists, policy makers, and the public into mixing together groups of people who require different kinds of help.

Progressives justify their discourse and agenda in the name of preventing dehumanization, but the effect has been the opposite. In defending the humanity of addicts, progressives ended up defending the inhumane conditions of street addiction.

The morality of victimology contains a version of all six values identified in Moral Foundations Theory. The problem is that those values are oriented around those defined as Victims in a particular context, to the exclusion of everyone else. But not even the most devoted homeless activists could do whatever drug-addicted homeless people demand of them. The demand that we give Victims special political authority is thus really a demand to give special political authority to those who claim to represent the supposed Victims, namely homelessness advocates.

The power of victimology lies in its moralizing discourse more than in any single set of laws. I was struck in my research that progressive intellectuals and activists have had a far greater impact on public policy, and the reality on the streets, than countless progressive politicians.

It is notable that while academics and activists are the most influential individuals in shaping homeless policy in San Francisco and Los Angeles, they are also the least accountable. As the problem has worsened, their cultural and political power has grown, while voters understandably blame their local elected leaders for the crisis.

Progressive advocates and policy makers alike blame the drug war, mass incarceration, and drug prohibition for the addiction and overdose crisis, even though the crisis resulted from liberalized attitudes and drug laws, first toward pharmaceutical opioids, and then toward all drugs. This view is, on the one hand, a defensive and ideological reaction. But it is also an abdication of responsibility.

And so while we should hold our elected officials responsible, we must also ask hard questions of the intellectual architects of their policies, and of the citizens, donors, and voters who empower them. What kind of a civilization leaves its most vulnerable people to use deadly substances and die on the streets? What kind of city regulates ice cream stores more strictly than drug dealers who kill 713 of its citizens in a single year? And what kind of people moralize about their superior treatment of the poor, people of color, and addicts while enabling and subsidizing the conditions of their death?

Automotive

Another sign Canada’s EV mandate is FAILING

By Dan McTeague

While other countries are moving away from EVs, the Carney government is doubling down.

Last week, it was reported that the feds are considering reimbursing car dealerships impacted by the sudden suspension of EV rebates. It’s becoming clear that Canada’s EV ambitions are failing as EV sales are plummeting and car manufacturers are backtracking on their EV plans.

It’s not too late for the Carney government to backdown from its EV mandate.

Dan McTeague explains.

conflict

One of the world’s oldest Christian Communities is dying in Syria. Will the West stay silent?

This article supplied by Troy Media.

By Susan Korah

By Susan Korah

The murder of Christians during Mass demands more than statements. Canada and its allies must act or share the blame

The June 22 suicide bombing at St. Elias Greek Orthodox Church in Damascus, which killed more than 25 people and injured over 60 during Mass, has devastated Syria’s Christian community and raised urgent concerns about their safety in a fragile, post-Assad Syria.

Activists close to the victims say the attack exposes the failure of the transitional Syrian government to protect religious minorities and underscores the need for immediate international pressure to hold the regime accountable. Without it, they warn, Syria’s ancient Christian presence could vanish.

Syria is home to one of the oldest Christian communities in the world, dating back to the first century. Though once numbering in the millions, its Christian community’s population has plummeted due to years of war, persecution and mass emigration. The attacker, linked to a shadowy extremist group called Saraya Ansari al-Sunna, opened fire on the 350-person congregation before detonating an explosive vest. The massacre has shattered the cautious optimism held by some Christians who believed Syria had turned a corner after 14 years of civil war.

“Immediately after the vicious attack, no official from the al-Sharaa government came forward to offer support except the only Christian in the cabinet, Hind Kabawat, Minister of Social Affairs,” said a Syrian Christian activist in the Toronto area who requested anonymity as he feared for his safety, even though he had emigrated to Canada years ago and serves on the refugee committee of a Melkite (Eastern rite Catholic) church.

“Our Patriarch John X issued a statement, respectfully appealing to the interim government to protect the lives and religious freedom of all Syria’s

faith groups,” he said.

Mario Bard, head of information with the pontifical charity Aid to the Church in Need Canada, said it’s imperative for the international community to take action.

“What a horrific attack,” he said. “Once again, a Christian minority community in the Middle East finds itself targeted. The local Church is already speaking of the death of its martyrs. It is a testament to the incredible faith, resilience and unshakable conviction of these communities. But that does not mean we can remain idle—far from it. ACN urges the international community not to look away and to act to ensure the protection of all religious communities in the Middle East.”

While urging governments to act, Bard reiterated that ACN will stand by its partners in Syria.

“We will continue to support the Christian community in Syria, as we have since the beginning of the war, including the Greek Orthodox Church of Antioch, with whom we have stood in the past and will continue to stand with now,” he said.

Nuri Kino of A Demand for Action, the Sweden-based humanitarian and advocacy organization he founded over 10 years ago to rally international support for Christians in Syria and Iraq targeted by ISIS for genocide, says the attack is not an isolated incident but part of a broader pattern in post-Assad Syria.

“It should be a wake-up call for the international community,” he said. “We are producing video clips and a report documenting atrocities against Christians after Assad’s fall, which will be distributed to governments that defend human rights. Our aim is to pressure the international community to ensure that financial aid given to Syria is conditional on the regime protecting the security and equal rights of Christians and all other citizens.”

As a major donor to Syria’s humanitarian recovery, Canada has leverage to tie funding to human rights protections. But so far, the Canadian government’s response has been muted, save for the usual diplomatic clichés

“Canada strongly condemns the terrorist attack at St. Elias Church in Damascus, which killed and injured civilians attending Mass on June 22, 2025. The targeting of civilians in a place of worship is deplorable,” said an email from the media relations team in response to a question posed to Foreign Affairs Minister Anita Anand. “Canada stands in solidarity with Syria’s Christian community and encourages the Syrian transitional authorities to work with partners to strengthen protections for all religious and ethnic minorities. Civilians must be protected, the dignity and human rights of all religious and ethnic groups must be upheld and perpetrators must be held accountable.”

Global Affairs has acknowledged that Syria’s security apparatus is under resourced and is not in full control of the country, as have others.

“The government’s military and security forces have not yet become organized under a central command and there is a power vacuum in that space,” said Ouhanes Shehrian, a Christian journalist based in Aleppo, Syria. “Different militias are in control of different parts of Syria, and this is a problem for the government.”

Although President Ahmed al-Sharaa’s HTS (Hayat Tahrir al-Sham) coalition led the effort to topple Assad, it now governs amid deep internal fractures. Al-Sharaa has tried to distance his party from its Islamist roots and has made some gestures toward minority groups, but observers warn that extremist factions still exert influence across various regions.

Canada, the U.S. and the EU lifted sanctions on Syria after the fall of the Assad government, a move Syriac Catholic Archbishop Jacques Mourad of Homs praised as a hopeful step for the Syrian people. Canada pledged $84 million in new funding for humanitarian assistance and temporarily eased existing sanctions to support democratization, stabilization and aid delivery during this transitional period.

Unless the international community demands real reforms and enforces conditions tied to aid, Christian leaders fear a future where minority

communities are simply left to endure or vanish.

As one local priest said after the bombing, “We prayed for peace, and we thought it had come. But now we bury our dead and wonder if we were wrong to hope.” Without swift action, what remains of Syria’s Christian presence may not survive the peace.

Susan Korah is Ottawa correspondent for The Catholic Register, a Troy Media Editorial Content Provider Partner

Troy Media empowers Canadian community news outlets by providing independent, insightful analysis and commentary. Our mission is to support local media in helping Canadians stay informed and engaged by delivering reliable content that strengthens community connections and deepens understanding across the country.

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoMatt Walsh slams Trump administration’s move to bury Epstein sex trafficking scandal

-

National2 days ago

National2 days agoDemocracy Watch Blows the Whistle on Carney’s Ethics Sham

-

Energy1 day ago

Energy1 day agoIs The Carney Government Making Canadian Energy More “Investible”?

-

Immigration1 day ago

Immigration1 day agoUnregulated medical procedures? Price Edward Islanders Want Answers After Finding Biomedical Waste From PRC-Linked Monasteries

-

Business1 day ago

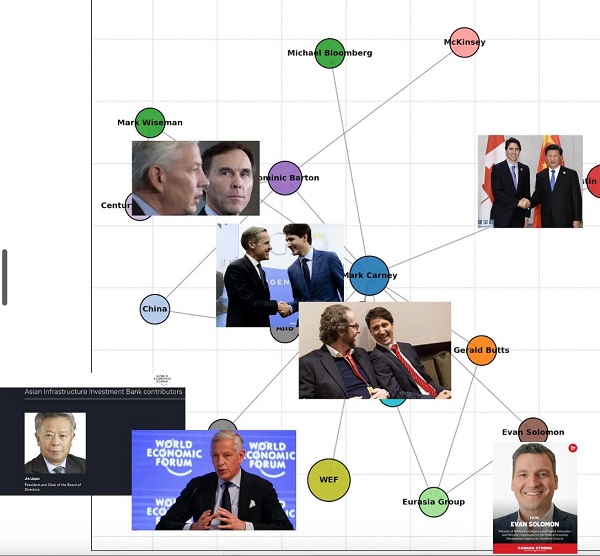

Business1 day agoDemocracy Watchdog Says PM Carney’s “Ethics Screen” Actually “Hides His Participation” In Conflicted Investments

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCompetition Bureau is right—Canada should open up competition in the air

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoIt’s Time To End Canada’s Protectionist Supply Management Regime

-

COVID-191 day ago

COVID-191 day agoFreedom Convoy leaders’ sentencing hearing to begin July 23 with verdict due in August