Economy

Canada should not want to lead the world on climate change policy

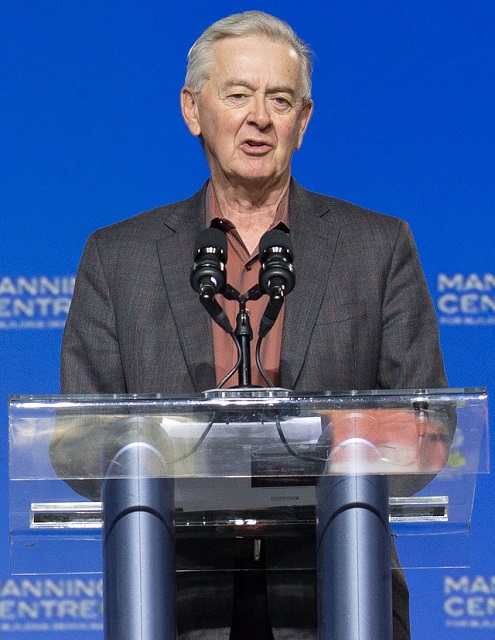

From the Fraser Institute

Some commentators in the media want the the federal Conservatives to take a leadership position on climate, and by extension make Canada a world leader on the journey to the low-carbon uplands of the future. This would be a mistake for three reasons.

First, unlike other areas such as trade, defence or central banking, where diplomats aim for realistic solutions to identifiable problems, in the global climate policy world one’s bona fides are not established by actions but by willingness to recite the words of an increasingly absurd creed. Take, for example, United Nations Secretary General António Guterres’ fanatical rhetoric about the “global boiling crisis” and his call for a “death knell” for fossil fuels “before they destroy our planet.” In that world no credit is given for actually reducing emissions unless you first declare that climate change is an existential crisis, that we are (again, to quote Guterres) at the “tip of a tipping point” of “climate breakdown” and that “humanity has become a weapon of mass extinction.” Any attempt to speak sensibly on the issue is condemned as denialism, whereas any amount of hypocrisy from jet-setting politicians, global bureaucrats and celebrities is readily forgiven as long as they parrot the deranged climate crisis lingo.

The opposite is also true. Unwillingness to state absurdities means actual accomplishments count for nothing. Compare President Donald Trump, who pulled out of the Paris treaty and disparaged climate change as unimportant, to Prime Minister Justin Trudeau who embraced climate emergency rhetoric and dispatched ever-larger Canadian delegations to the annual greenhouse gabfests. In the climate policy world, that made Canada a hero and the United States a villain. Meanwhile, thanks in part to expansion of natural gas supplies under the Trump administration, from 2015 to 2019 U.S. energy-based CO2 emissions fell by 3 per cent even as primary energy consumption grew by 3 per cent. In Canada over the same period, CO2 emissions fell only 1 per cent despite energy consumption not increasing at all. But for the purpose of naming heroes and villains, no one cared about the outcome, only the verbiage. Likewise, climate zealots will not credit Conservatives for anything they achieve on the climate file unless they are first willing to repeat untrue alarmist nonsense, and probably not even then.

On climate change, Conservatives should resolve to speak sensibly and use mainstream science and economic analysis, but that means rejecting climate crisis rhetoric and costly “net zero” aspirations. Which leads to the second problem—climate advocates love to talk about “solutions” but their track record is 40 years of costly failure and massive waste. Here again leadership status is tied to one’s willingness to dump ever-larger amounts of taxpayer money into impractical schemes loaded with all the fashionable buzzwords. The story is always the same. We need to hurry and embrace this exciting economic opportunity, which for some reason the private sector won’t touch.

There are genuine benefits to pursuing practical sensible improvements in the way we make and use fossil fuels. But the current and foreseeable state of energy technology means CO2 mitigation steps will be smaller and much slower than was the case for other energy side-effects such as acid rain and particulates. It has nothing to do with lack of “political will;” it’s an unavoidable consequence of the underlying science, engineering and economics. In this context, leadership means being willing sometimes to do nothing when all the available options yield negative net benefits.

That leads to the third problem—opportunity cost. Aspiring to “climate leadership” means not fixing any of the pressing economic problems we currently face. Climate policy over the past four decades has proven to be very expensive, economically damaging and environmentally futile. The migration of energy-intensive industry to China and India is a very real phenomenon and more than offsets the tiny emission-reduction measures Canada and other western countries pursued under the Kyoto Protocol.

The next government should start by creating a new super-ministry of Energy, Resources and Climate where long-term thinking and planning can occur in a collaborative setting, not the current one where climate policy is positioned at odds with—and antagonistic towards—everything else. The environment ministry can then return its focus to air and water pollution management, species and habitat conservation, meteorological services and other traditional environmental functions. The climate team should prepare another national assessment but this time provide much more historical data to help Canadians understand long-term observed patterns of temperature and precipitation rather than focusing so much on model simulations of the distant future under implausible emission scenarios.

The government should also move to extinguish “climate liability,” a legal hook on which dozens of costly nuisance lawsuits are proliferating here and elsewhere. Canada should also use its influence in the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change to reverse the mission creep, clean out the policy advocacy crowd and get the focus back on core scientific assessments. And we should lead a push to move the annual “COPs”—Conferences of the Parties to the Rio treaty—to an online format, an initiative that would ground enough jumbo jets each year to delay the melting of the ice caps at least a century.

Finally, the new Ministry of Energy, Resources and Climate should work with the provinces to find one region or municipality willing to be a demonstration project on the feasibility of relying only on renewables for electricity. We keep hearing from enthusiasts that wind and solar are the cheapest and best options, while critics point to their intermittency and hidden costs. Surely there must be one town in Canada where the councillors, fresh from declaring a climate crisis and buying electric buses, would welcome the chance to, as it were, show leadership. We could fit them out with all the windmills and solar panels they want, then disconnect them from the grid and see how it goes. And if upon further reflection no one is willing to try it, that would also be useful information.

In the meantime, the federal Conservatives should aim merely to do some sensible things that yield tangible improvements on greenhouse gas emissions without wrecking the economy. Maybe one day that will be seen as real leadership.

Author:

Business

Canada must address its birth tourism problem

By Sergio R. Karas for Inside Policy

One of the most effective solutions would be to amend the Citizenship Act, making automatic citizenship conditional upon at least one parent being a Canadian citizen or permanent resident.

Amid rising concerns about the prevalence of birth tourism, many Western democracies are taking steps to curb the practice. Canada should take note and reconsider its own policies in this area.

Birth tourism occurs when pregnant women travel to a country that grants automatic citizenship to all individuals born on its soil. There is increasing concern that birthright citizenship is being abused by actors linked to authoritarian regimes, who use the child’s citizenship as an anchor or escape route if the conditions in their country deteriorate.

Canada grants automatic citizenship by birth, subject to very few exceptions, such as when a child is born to foreign diplomats, consular officials, or international representatives. The principle known as jus soli in Latin for “right of the soil” is enshrined in Section 3(1)(a) of the Citizenship Act.

Unlike many other developed countries, Canada’s legislation does not consider the immigration or residency status of the parents for the child to be a citizen. Individuals who are in Canada illegally or have had refugee claims rejected may be taking advantage of birthright citizenship to delay their deportation. For example, consider the Supreme Court of Canada’s ruling in Baker v. Canada. The court held that the deportation decision for a Jamaican woman – who did not have legal status in Canada but had Canadian-born children – must consider the best interests of the Canadian-born children.

There is mounting evidence of organized birth tourism among individuals from the People’s Republic of China, particularly in British Columbia. According to a January 29 news report in Business in Vancouver, an estimated 22–23 per cent of births at Richmond Hospital in 2019–20 were to non-resident mothers, and the majority were Chinese nationals. The expectant mothers often utilize “baby houses” and maternity packages, which provide private residences and a comprehensive bundle of services to facilitate the mother’s experience, so that their Canadian-born child can benefit from free education and social and health services, and even sponsor their parents for immigration to Canada in the future. The financial and logistical infrastructure supporting this practice has grown, with reports of dozens of birth houses in British Columbia catering to a Chinese clientele.

Unconditional birthright citizenship has attracted expectant mothers from countries including Nigeria and India. Many arrive on tourist visas to give birth in Canada. The number of babies born in Canada to non-resident mothers – a metric often used to measure birth tourism – dropped sharply during the COVID-19 pandemic but has quickly rebounded since. A December 2023 report in Policy Options found that non-resident births constituted about 1.6 per cent of all 2019 births in Canada. That number fell to 0.7 per cent in 2020–2021 due to travel restrictions, but by 2022 it rebounded to one per cent of total births. That year, there were 3,575 births to non-residents – 53 per cent more than during the pandemic. Experts believe that about half of these were from women who travelled to Canada specifically for the purpose of giving birth. According to the report, about 50 per cent of non-resident births are estimated to be the result of birth tourism. The upward trend continued into 2023–24, with 5,219 non-resident births across Canada.

Some hospitals have seen more of these cases than others. For example, B.C.’s Richmond Hospital had 24 per cent of its births from non-residents in 2019–20, but that dropped to just 4 per cent by 2022. In contrast, Toronto’s Humber River Hospital and Montreal’s St. Mary’s Hospital had the highest rates in 2022–23, with 10.5 per cent and 9.4 per cent of births from non-residents, respectively.

Several developed countries have moved away from unconditional birthright citizenship in recent years, implementing more restrictive measures to prevent exploitation of their immigration systems. In the United Kingdom, the British Nationality Act abolished jus soli in its unconditional form. Now, a child born in the UK is granted citizenship only if at least one parent is a British citizen or has settled status. This change was introduced to prevent misuse of the immigration and nationality framework. Similarly, Germany follows a conditional form of jus soli. According to its Nationality Act, a child born in Germany acquires citizenship only if at least one parent has legally resided in the country for a minimum of eight years and holds a permanent residence permit. Australia also eliminated automatic birthright citizenship. Under the Australian Citizenship Act, a child born on Australian soil is granted citizenship only if at least one parent is an Australian citizen or permanent resident. Alternatively, if the child lives in Australia continuously for ten years, they may become eligible for citizenship through residency. These policies illustrate a global trend toward limiting automatic citizenship by birth to discourage birth tourism.

In the United States, Section 1 of the Citizenship Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution prescribes that “All persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States and of the State wherein they reside.” The Trump administration has launched a policy and legal challenge to the longstanding interpretation that every person born in the US is automatically a citizen. It argues that the current interpretation incentivizes illegal immigration and results in widespread abuse of the system.

On January 20, 2025, President Donald Trump issued Executive Order 14156: Protecting the Meaning and Value of American Citizenship, aimed at ending birthright citizenship for children of undocumented migrants and those with lawful but temporary status in the United States. The executive order stated that the Fourteenth Amendment’s Citizenship Clause “rightly repudiated” the Supreme Court’s “shameful decision” in the Dred Scott v. Sandford case, which dealt with the denial of citizenship to black former slaves. The administration argues that the Fourteenth Amendment “has never been interpreted to extend citizenship universally to anyone born within the United States.” The executive order claims that the Fourteenth Amendment has “always excluded from birthright citizenship persons who were born in the United States but not subject to the jurisdiction thereof.” The order outlines two categories of individuals that it claims are not subject to United States jurisdiction and thus not automatically entitled to citizenship: a child of an undocumented mother and father who are not citizens or lawful permanent residents; and a child of a mother who is a temporary visitor and of a father who is not a citizen or lawful permanent resident. The executive order attempts to make ancestry a criterion for automatic citizenship. It requires children born on US soil to have at least one parent who has US citizenship or lawful permanent residency.

On June 27, 2025, the US Supreme Court in Trump v. CASA, Inc. held that lower federal courts exceed their constitutional authority when issuing broad, nationwide injunctions to prevent the Trump administration from enforcing the executive order. Such relief should be limited to the specific plaintiffs involved in the case. The Court did not address whether the order is constitutional, and that will be decided in the future. However, this decision removes a major legal obstacle, allowing the administration to enforce the policy in areas not covered by narrower injunctions. Since the order could affect over 150,000 newborns each year, future decisions on the merits of the order are still an especially important legal and social issue.

In addition to the executive order, the Ban Birth Tourism Act – introduced in the United States Congress in May 2025 – aims to prevent women from entering the country on visitor visas solely to give birth, citing an annual 33,000 births to tourist mothers. Simultaneously, the State Department instructed US consulates abroad to deny visas to applicants suspected of “birth tourism,” reinforcing a sharp policy pivot.

In light of these developments, Canada should be wary. It may see an increase in birth tourism as expectant mothers look for alternative destinations where their children can acquire citizenship by birth.

Canadian immigration law does not prevent women from entering the country on a visitor visa to give birth. The Immigration and Refugee Protection Act (IRPA) and the associated regulations do not include any provisions that allow immigration officials or Canada Border Services officers to deny visas or entry based on pregnancy. Section 22 of the IRPA, which deals with temporary residents, could be amended. However, making changes to regulations or policy would be difficult and could lead to inconsistent decisions and a flurry of litigation. For example, adding questions about pregnancy to visa application forms or allowing officers to request pregnancy tests in certain high-risk cases could result in legal challenges on the grounds of privacy and discrimination.

In a 2019 Angus Reid Institute survey, 64 per cent of Canadians said they would support changing the law to stop granting citizenship to babies born in Canada to parents who are only on tourist visas. One of the most effective solutions would be to amend Section 3(1)(a) of the Citizenship Act, making it mandatory that at least one parent be a Canadian citizen or permanent resident for a child born in Canada to automatically receive citizenship. Such a model would align with citizenship legislation in countries like the UK, Germany, and Australia, where jus soli is conditional on parental status. Making this change would close the current loophole that allows birth tourism, without placing additional pressure on visa officers or requiring new restrictions on tourist visas. It would retain Canada’s inclusive citizenship framework while aligning with practices in other democratic nations.

Canada currently lacks a proper and consistent system for collecting data on non-resident births. This gap poses challenges in understanding the scale and impact of birth tourism. Since health care is under provincial jurisdiction, the responsibility for tracking and managing such data falls primarily on the provinces. However, there is no national framework or requirement for provinces or hospitals to report the number of births by non-residents, leading to fragmented and incomplete information across the country. One notable example is BC’s Richmond Hospital, which has become a well-known birth tourism destination. In the 2017–18 fiscal year alone, 22 per cent of all births at Richmond Hospital were to non-resident mothers. These births generated approximately $6.2 million in maternity fees, out of which $1.1 million remained unpaid. This example highlights not only the prevalence of the practice but also the financial burden it places on the provincial health care programs. To better address the issue, provinces should implement more robust data collection practices. Information should include the mother’s residency or visa status, the total cost of care provided, payment outcomes (including outstanding balances), and any necessary medical follow-ups.

Reliable and transparent data is essential for policymakers to accurately assess the scope of birth tourism and develop effective responses. Provinces should strengthen data collection practices and consider introducing policies that require security deposits or proof of adequate medical insurance coverage for expectant mothers who are not covered by provincial healthcare plans.

Canada does not currently record the immigration or residency status of parents on birth certificates, making it difficult to determine how many children are born to non-resident or temporary resident parents. Including this information at the time of birth registration would significantly improve data accuracy and support more informed policy decisions. By improving data collection, increasing transparency, and adopting preventive financial safeguards, provinces can more effectively manage the challenges posed by birth tourism, and the federal government can implement legislative reforms to deal with the problem.

Sergio R. Karas, principal of Karas Immigration Law Professional Corporation, is a certified specialist in Canadian citizenship and immigration law by the Law Society of Ontario. He is co-chair of the ABA International Law Section Immigration and Naturalization Committee, past chair of the Ontario Bar Association Citizenship and Immigration Section, past chair of the International Bar Association Immigration and Nationality Committee, and a fellow of the American Bar Foundation. He can be reached at [email protected]. The author is grateful for the contribution to this article by Jhanvi Katariya, student-at-law.

Business

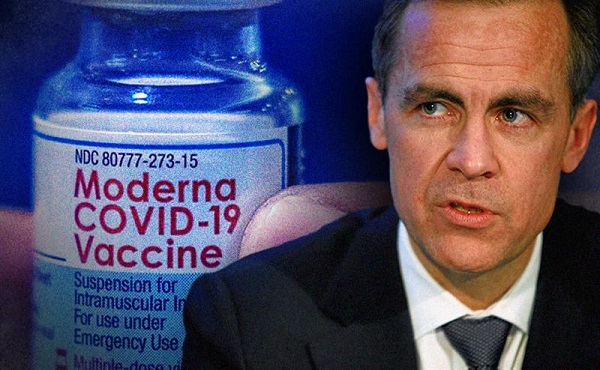

Mark Carney’s Fiscal Fantasy Will Bankrupt Canada

By Gwyn Morgan

Mark Carney was supposed to be the adult in the room. After nearly a decade of runaway spending under Justin Trudeau, the former central banker was presented to Canadians as a steady hand – someone who could responsibly manage the economy and restore fiscal discipline.

Instead, Carney has taken Trudeau’s recklessness and dialled it up. His government’s recently released spending plan shows an increase of 8.5 percent this fiscal year to $437.8 billion. Add in “non-budgetary spending” such as EI payouts, plus at least $49 billion just to service the burgeoning national debt and total spending in Carney’s first year in office will hit $554.5 billion.

Even if tax revenues were to remain level with last year – and they almost certainly won’t given the tariff wars ravaging Canadian industry – we are hurtling toward a deficit that could easily exceed 3 percent of GDP, and thus dwarf our meagre annual economic growth. It will only get worse. The Parliamentary Budget Officer estimates debt interest alone will consume $70 billion annually by 2029. Fitch Ratings recently warned of Canada’s “rapid and steep fiscal deterioration”, noting that if the Liberal program is implemented total federal, provincial and local debt would rise to 90 percent of GDP.

This was already a fiscal powder keg. But then Carney casually tossed in a lit match. At June’s NATO summit, he pledged to raise defence spending to 2 percent of GDP this fiscal year – to roughly $62 billion. Days later, he stunned even his own caucus by promising to match NATO’s new 5 percent target. If he and his Liberal colleagues follow through, Canada’s defence spending will balloon to the current annual equivalent of $155 billion per year. There is no plan to pay for this. It will all go on the national credit card.

This is not “responsible government.” It is economic madness.

And it’s happening amid broader economic decline. Business investment per worker – a key driver of productivity and living standards – has been shrinking since 2015. The C.D. Howe Institute warns that Canadian workers are increasingly “underequipped compared to their peers abroad,” making us less competitive and less prosperous.

The problem isn’t a lack of money; it’s a lack of discipline and vision. We’ve created a business climate that punishes investment: high taxes, sluggish regulatory processes, and politically motivated uncertainty. Carney has done nothing to reverse this. If anything, he’s making the situation worse.

Recall the 2008 global financial meltdown. Carney loves to highlight his role as Bank of Canada Governor during that time but the true credit for steering the country through the crisis belongs to then-prime minister Stephen Harper and his finance minister, Jim Flaherty. Facing the pressures of a minority Parliament, they made the tough decisions that safeguarded Canada’s fiscal foundation. Their disciplined governance is something Carney would do well to emulate.

Instead, he’s tearing down that legacy. His recent $4.3 billion aid pledge to Ukraine, made without parliamentary approval, exemplifies his careless approach. And his self-proclaimed image as the experienced technocrat who could go eyeball-to-eyeball against Trump is starting to crack. Instead of respecting Carney, Trump is almost toying with him, announcing in June, for example that the U.S. would pull out of the much-ballyhooed bilateral trade talks launched at the G7 Summit less than two weeks earlier.

Ordinary Canadians will foot the bill for Carney’s fiscal mess. The dollar has weakened. Young Canadians – already priced out of the housing market – will inherit a mountain of debt. This is not stewardship. It’s generational theft.

Some still believe Carney will pivot – that he will eventually govern sensibly. But nothing in his actions supports that hope. A leader serious about economic renewal would cancel wasteful Trudeau-era programs, streamline approvals for energy and resource projects, and offer incentives for capital investment. Instead, we’re getting more borrowing and ideological showmanship.

It’s no longer credible to say Carney is better than Trudeau. He’s worse. Trudeau at least pretended deficits were temporary. Carney has made them permanent – and more dangerous.

This is a betrayal of the fiscal stability Canadians were promised. If we care about our credit rating, our standard of living, or the future we are leaving our children, we must change course.

That begins by removing a government unwilling – or unable – to do the job.

Canada once set an economic example for others. Those days are gone. The warning signs – soaring debt, declining productivity, and diminished global standing – are everywhere. Carney’s defenders may still hope he can grow into the job. Canada cannot afford to wait and find out.

The original, full-length version of this article was recently published in C2C Journal.

Gwyn Morgan is a retired business leader who was a director of five global corporations.

-

Opinion1 day ago

Opinion1 day agoPreston Manning: Three Wise Men from the East, Again

-

Uncategorized2 days ago

Uncategorized2 days agoCNN’s Shock Climate Polling Data Reinforces Trump’s Energy Agenda

-

Addictions1 day ago

Addictions1 day agoWhy B.C.’s new witnessed dosing guidelines are built to fail

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCarney Liberals quietly award Pfizer, Moderna nearly $400 million for new COVID shot contracts

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoMark Carney’s Fiscal Fantasy Will Bankrupt Canada

-

Energy22 hours ago

Energy22 hours agoActivists using the courts in attempt to hijack energy policy

-

Alberta14 hours ago

Alberta14 hours agoAlberta ban on men in women’s sports doesn’t apply to athletes from other provinces

-

National14 hours ago

National14 hours agoCanada’s immigration office admits it failed to check suspected terrorists’ background