armed forces

While war rages in the Middle East and Europe, Canada’s military is less capable than ever

From the MacDonald Laurier Institute

By Richard Shimooka

There are no good solutions to this problem, only less bad alternatives.

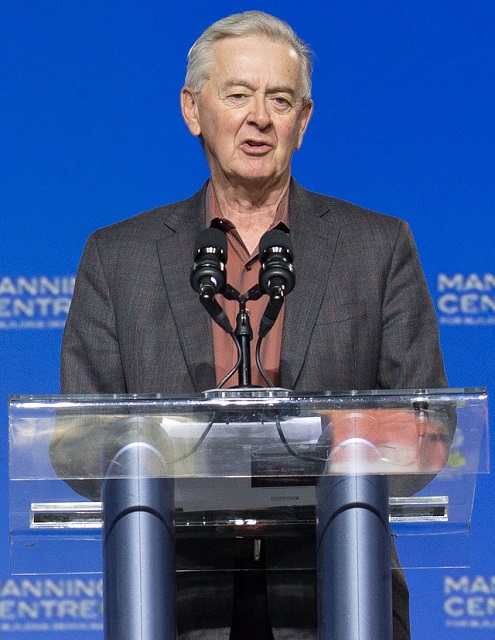

Over a decade ago, I had the opportunity to interview Jim Judd, the former deputy minister of national defence. After all these years, one quote still sticks out to me:

People assume because DND has 60,000 personnel and a budget of 12 billion dollars it should be able to do something, but there are quite severe practical limitations to its capability. In my view, it was not all that well understood outside of military circles.

Judd’s comment seems even more relevant today than it was eleven years ago. The ongoing Russian war in Ukraine, Chinese aggression in the West Pacific, and now the brutal incursion by Hamas into Israel from Gaza have stripped away any facade that the international system will be more peaceful or stable than in the 20th century. For most major liberal democracies, these events have shaken the complacency that has prevailed since the end of the Cold War: that is except for Canada. The recent announcement that the defence department will need to shoulder a $1 billion dollar budget cut over the next three years clearly illustrates the lack of awareness of this government on the international moment.

Yet, like Judd’s comment, there is little understanding amongst the public of how the military functions, and the consequences of these cuts are critical. While many may be dimly aware that the armed forces are facing a challenging situation, the actual details and the future outcome are only known to a precious few. This article will try to address that.

What will become apparent is that political decisions have simultaneously over-deployed the Canadian Armed Forces (CAF) while neglecting to invest in its capabilities. This has upset the fragile sustainment system, leaving its actual operational capability in tatters. The military has become a token force abroad and is even unlikely to be able to provide for Canada’s own defence in the near future. What follows is not a worse-case scenario, but the most likely outcome given the present situation and future trends.

The first step is to understand the aims of the CAF and how it is structured to achieve them. With the exception of the CF-18’s tactical fighter fleet’s continental defence mission, much of the CAF’s active duty military is organized to undertake expeditionary operations abroad. This should not be surprising. Other than the airborne threat of Russian aircraft, there are very limited direct naval and land threats to Canada. Most operations are abroad. Yet units are not able to deploy indefinitely—personnel need rotation home for rest, while equipment needs time for maintenance and overhaul. Furthermore, they require time to undertake personal development training as well as building up their forces prior to deployment.

In order to sustain units in the field the CAF employs something known as the “managed readiness system.” Essentially the system rotates units between deployment, recuperation, and training. This usually means a 1/3 ratio: for every one unit deployed into the field, two are in the other phases of a cycle. This isn’t a universal ratio: the Army’s field units can operate between a 1/2 to 1/4 ratio, the Navy’s frigates cycle is closer to 1/3.5 in practice, and submarines are 1/4 (this is largely due to the greater maintenance requirements these vessels require in order to operate safely). This was a major consideration for acquiring the four Victoria class submarines from the United Kingdom in the 1990s as it would ensure in practice that one would always be available for operation.

Tactical fighters operate differently, but a 1/4 ratio roughly captures the size of the fleet required to keep a sizeable force available for operations. Furthermore, as equipment ages, they also require more time and effort to maintain and overhaul.

In practical terms, the CAF’s objectives since the end of the Cold War have been to sustain four frigates for deployment, 18 CF-18 fighter jets for peacetime operations (12 on alert in Canada and six abroad for NATO), and a half brigade’s worth of soldiers (2000-2500) with ancillary capabilities. Among Western states, this is a fairly small contribution. For example, the United Kingdom, with only 30 percent greater GDP than Canada, potentially can sustain three brigades, totalling over 10,000 soldiers in the field that are able to fight in very high-intensity environments.

As we’re about to see, Canada falls far short of even its modest objectives, with the gap widening for the foreseeable future.

In the eight years since the Trudeau Government assumed office, two broad trends have been discernible. The first is an expanded international vision for the CAF, with large deployments in Europe and the Middle East, as well as a more active naval and air presence in the Pacific. This, as well as increased maintenance requirements for an aging equipment base, are the major cost drivers for the CAF. At the same time, while Canada’s defence policy, Strong, Secure, Engaged, promised a fully funded and structured recapitalization of the military, it has not been delivered—even within two years of the document’s promulgation, National Defence had already failed to spend $8 billion dollars budgeted to it. Thus, overuse tied with undercapitalization has resulted in the entire range of operational capabilities deteriorating over the past decade. Some modestly so, others much more drastically.

Navy

Let’s start with the Navy. For much of the 2000s, the twelve Halifax Class frigates were run hard to meet various commitments after 9/11. Now reaching thirty years of age, these vessels have undergone excessive levels of service and are showing their age. The foremost example is the HMCS Toronto, which has been undergoing refit since 2022. It has severe hull corrosion which has left her in a dilapidated state and may require hundreds of millions of dollars in repairs. The vastly increased maintenance requirements are visible across the class. In 2002 each Halifax class frigates’ docking work period (DWP) required around 200,000 man-hours to complete. Current DWPs now average 1.2 million hours, and will likely reach 1.5 million by the end of the decade. This translates into a significant cost increase and affects ship availability. With these constraints, the original objective of four vessels operational at any one time is completely unachievable: Canada at present effectively has only two frigates (with a third potentially available in some instances), which will become increasingly difficult to sustain in the coming years.

Canada’s submarines are in a similar shape. The grounding of the HMCS Corner Brook in 2011, and its subsequent dockyard accident in 2020, has effectively left the fleet with only three submarines in the managed readiness system, often leaving none available for operations. With fewer deployment opportunities, crew regeneration has suffered, damaging the remaining personnel morale and impacting the skill base that is critical for operating such a highly complex capability.

Army

The Army is not in much better shape, although its challenges are somewhat different from the other services. The expansion of the Latvia mission to approximately 2,000 soldiers will effectively utilize the vast majority of the units available at any given time through managed readiness. However the demands, like during the Afghanistan era, will stretch the system and have a number of negative consequences. The first is whether the mission can be sustained for more than two years—there simply are not enough soldiers available in the coming years given the ongoing personnel shortages.

Another almost certain consequence will be the curtailment of unit training across the Army, as there will be fewer personnel available. This places troops at greater risk even for a peacetime operation like in Latvia. Russia has continually targeted Canadian soldiers with active measures campaigns to discredit their presence in the country, something that requires training and vigilance to avoid. This also ignores that the CAF will not deploy to Latvia with many basic capabilities, such as ambulances and air defence systems that can defend against UAVs or mobile artillery, all of which are basic capabilities for operating in a war today.

These issues are compounded by the increasing number of domestic operations surrounding disaster relief the Army has been tasked with, such as helping to deal with the wildfires that raged this past summer. While these are generally handled by the reserves, the growing scale of these events, as well as the tendency to use the military as the force of first resort in these cases, is further straining its already weakened force generation system.

Air Force

Perhaps the most precipitous decline is with the RCAF’s tactical fighter fleet of CF-18s. Canada is currently in the process of shrinking its fleet to 37 aircraft while preparing for the transition to the F-35. The fleet size is sufficient only to sustain domestic NORAD operations, a reality underlined by the announcement last December that the RCAF would withdraw from NATO commitments for the foreseeable future. Even more problematic is the lack of pilots and support personnel, which may even lead to the Air Force being unable to fulfill the NORAD alert mission requirements in full. As the F-35 transition gets underway in the coming years, there are fears that there will be insufficient personnel to staff both aircraft types, which will likely result in fewer available CF-18s to meet the alert role.

The state of the tactical fighter fleet can be directly attributed to the Liberal government’s decision to scrap the acquisition of the F-35 in 2015. While some suggested the competition “built trust” and confidence for the decision, the process essentially wrecked the ability of the Air Force to provide even the most basic level of security for the country. Even more ironic was that the government tried to implement an end-run around a competition through the interim buy of 18 F/A-18E/F Super Hornets, justified by the need to meet both the NORAD and NATO missions simultaneously. Now, seven years later, Canada has effectively ended one mission and faces the possibility that it will not even be able to meet its most basic mission of defending the country’s airspace.

Solutions

So, what can be done? Unfortunately, there are no good outcomes for the government, only less bad alternatives. Avoiding the worst-case scenario will require multiple lines of effort. Overall it requires the forces to reduce its overseas commitments while trying to revitalize its standing forces by accelerating modernization and recruitment.

The first step is to approach the United States and close allies and frankly acknowledge the situation the government has placed itself in. To some degree, they are already aware: recent moves like the exclusion of AUKUS and the U.K.’s offer to assist in arctic security implicitly recognize Canada’s weakness. However, to reconstitute the military effectively will require the CAF to withdraw from some of its long-standing commitments. For example, it is questionable whether the Latvia expansion is responsible given the state of the Army. There is a high probability that the mission’s demands are unsustainable in the long run, to the point where CAF will have to withdraw significant portions of its commitment to the Baltics or risk a collapse of its managed readiness system. Maintaining the operation’s present size and/or undertaking shorter periodic deployments of units are much more achievable alternatives given the current constraints.

Of primary importance, though, is that the personnel and procurement systems require reforms. Pouring more money and resources into the present systems is like pouring water into a bucket with holes. The holes must be plugged before anything else can proceed. Both systems must address the new realities in their respective areas, which will require substantial changes to how the government operates. Once this is accomplished, raising funding levels that meet the NATO two percent of GDP threshold will be critical—there are far too many deferred maintenance and procurements programs that need to be addressed immediately if the CAF wants to remain viable.

Finally, budget certainty is essential. Cutting a billion in funding and delaying implementation of Strong, Secure, Engaged further undercuts the military’s state. Unpredictable budget environments are a prime cause of delays and larger cost overruns, both on procurement projects and for operations—issues that the CAF and Canada cannot afford anymore.

The current situation was utterly predictable even seven years ago. Now that the country is in this quagmire, it will require a herculean effort to get out of it.

Richard Shimooka is a Hub contributing writer and a senior fellow at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute who writes on defence policy.

armed forces

Canada’s Military Can’t Be Fixed With Cash Alone

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

By Lt. Gen. (Ret.) Michel Maisonneuve

Canada’s military is broken, and unless Ottawa backs its spending with real reform, we’re just playing politics with national security

Prime Minister Mark Carney’s surprise pledge to meet NATO’s defence spending target is long overdue, but without real reform, leadership and a shift away from bureaucracy and social experimentation, it risks falling short of what the moment demands.

Canada committed in 2014 to spend two per cent of its gross national product on defence—a NATO target meant to ensure collective security and more equitable burden-sharing. We never made it past 1.37 per cent, drawing criticism from allies and, in my view, breaching our obligation. Now, the prime minister says we’ll hit the target by the end of fiscal year 2025-26. That’s welcome news, but it comes with serious challenges.

Reaching the two per cent was always possible. It just required political courage. The announced $9 billion in new defence spending shows intent, and Carney’s remarks about protecting Canadians are encouraging. But the reality is our military readiness is at a breaking point. With global instability rising—including conflicts in Ukraine and the Middle East—Canada’s ability to defend its territory or contribute meaningfully to NATO is under scrutiny. Less than half of our army vehicles, ships and aircraft are currently operational.

I’m told the Treasury Board has already approved the new funds, making this more than just political spin. Much of the money appears to be going where it’s most needed: personnel. Pay and benefit increases for serving members should help with retention, and bonuses for re-enlistment are reportedly being considered. Recruiting and civilian staffing will also get a boost, though I question adding more to an already bloated public service. Reserves and cadet programs weren’t mentioned but they also need attention.

Equipment upgrades are just as urgent. A new procurement agency is planned, overseen by a secretary of state—hopefully with members in uniform involved. In the meantime, accelerating existing projects is a good way to ensure the money flows quickly. Restocking ammunition is a priority. Buying Canadian and diversifying suppliers makes sense. The Business Council of Canada has signalled its support for a national defence industrial strategy. That’s encouraging, but none of it will matter without follow-through.

Infrastructure is also in dire shape. Bases, housing, training facilities and armouries are in disrepair. Rebuilding these will not only help operations but also improve recruitment and retention. So will improved training, including more sea days, flying hours and field operations.

All of this looks promising on paper, but if the Department of National Defence can’t spend funds effectively, it won’t matter. Around $1 billion a year typically lapses due to missing project staff and excessive bureaucracy. As one colleague warned, “implementation [of the program] … must occur as a whole-of-government activity, with trust-based partnerships across industry and academe, or else it will fail.”

The defence budget also remains discretionary. Unlike health transfers or old age security, which are legally entrenched, defence funding can be cut at will. That creates instability for military suppliers and risks turning long-term procurement into a political football. The new funds must be protected from short-term fiscal pressure and partisan meddling.

One more concern: culture. If Canada is serious about rebuilding its military, we must move past performative diversity policies and return to a warrior ethos. That means recruiting the best men and women based on merit, instilling discipline and honour, and giving them the tools to fight and, if necessary, make the ultimate sacrifice. The military must reflect Canadian values, but it is not a place for social experimentation or reduced standards.

Finally, the announcement came without a federal budget or fiscal roadmap. Canada’s deficits continue to grow. Taxpayers deserve transparency. What trade-offs will be required to fund this? If this plan is just a last-minute attempt to appease U.S. President Donald Trump ahead of the G7 or our NATO allies at next month’s summit, it won’t stand the test of time.

Canada has the resources, talent and standing to be a serious middle power. But only action—not announcements—will prove whether we truly intend to be one.

The NATO summit is over, and Canada was barely at the table. With global threats rising, Lt. Gen. (Ret.) Michel Maisonneuve joins David Leis to ask: How do we rebuild our national defence—and why does it matter to every Canadian? Because this isn’t just about security. It’s about our economy, our identity, and whether Canada remains sovereign—or becomes the 51st state.

Michel Maisonneuve is a retired lieutenant-general who served 45 years in uniform. He is a senior fellow at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy and author of In Defence of Canada: Reflections of a Patriot (2024).

armed forces

Mark Carney Thinks He’s Cinderella At The Ball

And we all pay when the dancing ends

How to explain Mark Carney’s obsession with Europe and his lack of attention to Canada’s economy and an actual budget?

Carney’s pirouette through NATO meetings, always in his custom-tailored navy blue power suits, carries the desperate whiff of an insecure, small-town outsider who has made it big but will always yearn for old-money credibility. Canada is too young a country, too dynamic and at times a bit too vulgar to claim equal status with Europe’s formerly magnificent and ancient cultures — now failed under the yoke of globalism.

Hysterical foreign policy, unchecked immigration, burgeoning censorship and massive income disparity have conquered much of the continent that many of us used to admire and were even somewhat intimidated by. But we’ve moved on. And yet Carney seems stuck, seeking approval and direction from modern Europe — a place where, for most countries, the glory days are long gone.

Carney’s irresponsible financial commitment to NATO is a reckless and unnecessary expenditure, given that many Canadians are hurting. But it allowed Carney to pick up another photo of himself glad-handing global elites to whom he just sold out his struggling citizens.

From the Globe and Mail

“Prime Minister Mark Carney has committed Canada to the biggest increase in military spending since the Second World War, part of a NATO pledge designed to address the threat of Russian expansionism and to keep Donald Trump from quitting the Western alliance.

Mr. Carney and the leaders of the 31 other member countries issued a joint statement Wednesday at The Hague saying they would raise defence-related spending to the equivalent of 5 per cent of their gross domestic product by 2035.

NATO Secretary-General Mark Rutte said the commitment means “European allies and Canada will do more of the heavy lifting” and take “greater responsibility for our shared security.”

For Canada, this will require spending an additional $50-billion to $90-billion a year – more than doubling the existing defence budget to between $110-billion and $150-billion by 2035, depending on how much the economy grows. This year Ottawa’s defence-related spending is due to top $62-billion.”

You’ll note that spending money we don’t have in order to keep President Trump happy is hardly an elbows up moment, especially given that the pledge followed Carney’s embarrassing interactions with Trump at the G7. I’m all for diplomacy but sick to my teeth of Carney’s two-faced approach to everything. There is no objective truth to anything our prime minister touches. Watch the first few minutes of the video below.

The portents are bad. This from the Globe:

We are poorer than we think. Canadians running their retirement numbers are shining light in the dark corners of household finances in this country. The sums leave many “anxious, fearful and sad about their finances,” according to a Healthcare of Ontario Pension Plan survey recently reported in these pages.

Fifty-two per cent of us worry a lot about our personal finances. Fifty per cent feel frustrated, 47 per cent feel emotionally drained and 43 per cent feel depressed. There is not one survey indicator to suggest Canadians have made financial progress in 2025 compared with 2024.

The video below is a basic “F”- you to Canadians from a Prime Minister who smirks and roles his eyes when questioned about his inept money management.

He did spill the beans to CNN with this unsettling revelation about the staggering numbers we are talking about:

Signing on to NATO’s new defence spending target could cost the federal treasury up to $150 billion a year, Prime Minister Mark Carney said Tuesday in advance of the Western military alliance’s annual summit.

The prime minister made the comments in an interview with CNN International.

“It is a lot of money,” Carney said.

This guy was a banker?

We are witnessing the political equivalent of a vain woman who blows her entire paycheque to look good for an aspirational event even though she can’t afford food or rent. Yes, she sparkled for a moment, but in reality her domaine is crumbling. All she has left are the photographs of her glittery night. Our Prime Minister is collecting his own album of power-proximity photos he can use to wallpaper over his failures as our economy collapses.

The glass slipper doesn’t fit.

Trish Wood is Critical is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Invite your friends and earn rewards

-

Uncategorized13 hours ago

Uncategorized13 hours agoCNN’s Shock Climate Polling Data Reinforces Trump’s Energy Agenda

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days ago103 Conflicts and Counting Unprecedented Ethics Web of Prime Minister Mark Carney

-

illegal immigration1 day ago

illegal immigration1 day agoICE raids California pot farm, uncovers illegal aliens and child labor

-

Energy1 day ago

Energy1 day agoLNG Export Marks Beginning Of Canadian Energy Independence

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCarney government should apply lessons from 1990s in spending review

-

Entertainment24 hours ago

Entertainment24 hours agoStudy finds 99% of late-night TV guests in 2025 have been liberal

-

Frontier Centre for Public Policy13 hours ago

Frontier Centre for Public Policy13 hours agoCanada’s New Border Bill Spies On You, Not The Bad Guys

-

Opinion5 hours ago

Opinion5 hours agoPreston Manning: Three Wise Men from the East, Again