MacDonald Laurier Institute

Trudeau is utterly determined to control the media: Peter Menzies

From the MacDonald Laurier Institute

By Peter Menzies

The government has broken new ground by involving itself in the business of judging the journalistic bona fides of news organizations.

The most progressive government in Canada’s history – the one under the towering command of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau – is fast building a reputation as the least liberal administration to have ruled the nation.

Just ask no less a personality than Piers Morgan.

“If you take Trudeau, for example, he banged on about Trump being a fascist, when he is the number one woke fascist in the world,” the English broadcaster and TV presenter recently told America’s Fox News. “The most woke human being alive.”

There’s little question Trudeau’s image as the world’s postmodern Prince Charming took a sharp turn for the worse two years ago with the unprecedented invocation of the Emergencies Act to suppress anti-government protests.

What’s more unsettling for civil libertarians is the thought that the Emergencies Act invocation wasn’t an aberration but part of a pattern of behaviour indicating that, while the ruling party may be Liberal, its instincts are anything but.

Its determination to control media – a hallmark of authoritarianism – has certainly raised eyebrows.

The Online Streaming Act, for instance, was only supposed to be about getting “money from web giants” such as Netflix and Disney+ to ensure government-preferred Canadian film and television content continued to be produced. But the act gave the Canadian Radio-television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) sweeping powers over any audio or video content published on the internet, even including podcasts.

Fears were also raised that YouTube and TikTok would be forced by the CRTC to give preferential treatment to its approved content over that produced by those not subscribing to regulatory and Canada Media Fund expectations. The fact the CRTC is involved has further raised fears about the potential for a wave of censorship.

The regulator insists that it does not engage in censorship. But the fact it was doing exactly that – sanctioning Radio Canada for using the N-word and banning RT (Russian State television) while swearing that it wasn’t a censor – didn’t build public confidence in the credibility of its protestations.

When the CRTC accepted a complaint from Egale Canada (a 2SLGBTQI advocacy group) asking that it remove Fox News from its list of approved foreign broadcasters for “repeatedly and regularly” violating broadcasting standards, it was clear that the CRTC is open to making decisions on what Canadians may or may not watch. In other words: censorship. The Commission is composed of a chair, two vice chairs and six regional commissioners, each of whom is appointed by cabinet.

The government has also broken new ground by involving itself in the business of judging the journalistic bona fides of news organizations. Two programs initially announced as temporary – the Local Journalism Initiative and the Journalism Labour Tax Credit – have now doubled in size and appear to be permanent. A government-appointed panel decides which organizations are Qualified Canadian Journalism Organizations (and which aren’t). And while all involved insist the panel functions independently, it nevertheless reports to the Heritage Minister who reports to the Prime Minister’s Office which reports to a prime minister who appears obsessed with the need to control “misinformation” and “disinformation.”

That issue could very well be at the heart of what could become the Trudeau government’s most illiberal legislation yet – the Online Harms Act.

First promised in 2019 to ensure a suite of already-illegal behaviours including child porn and terrorism recruitment were suppressed, the Act’s core concept of giving a Digital Safety Commissioner power to order swift content removal has met with stiff resistance.

Pre-Elon Musk Twitter (X) put it this way:

“People around the world have been blocked from accessing Twitter and other services in a similar manner as the one proposed by Canada by multiple authoritarian governments (China, North Korea, and Iran for example) …”

Three Heritage Ministers have failed to find a way to legally reign in the internet in a fashion that satisfies the prime minister, so the matter has passed to the hands of Justice Minister Arif Virani.

Speculation in Ottawa is that Virani may be named as a Minister of State for Heritage, permitting him to try to come up with legislation that won’t – as did the Online Streaming Act and the Online News Act – trigger outrage when it’s introduced in the spring.

It remains to be seen if the Act will include extreme measures, like the policy resolution passed at last May’s Liberal convention to ban online media from using unnamed sources.

So, strap yourself in. The curtain may be about to rise on the most illiberal Liberal move yet.

Alberta

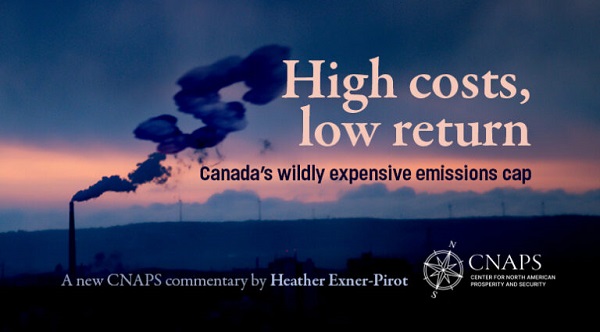

High costs, low returns – Canada’s wildly expensive emissions cap

In this new commentary, Director of Energy, Natural Resources, and Environment Heather Exner-Pirot reveals why the Canadian government’s oil and gas emissions cap isn’t just expensive – it’s economic insanity.

Canada is the world’s third-largest exporter of oil, fourth-largest producer, and top source of imports to the United States. Much of Canada’s oil wealth is concentrated in the oil sands in northern Alberta, which hosts 99 percent of the country’s enormous oil endowment: about 160 billion barrels of proven reserves, of a total resource of approximately 1.8 trillion barrels. This is the major source of oil to the United States refinery complex, a large part of which is optimized for the oil sands’ heavy oil.

Reliability of energy supply has remerged as a major geopolitical issue. Canadian oil and gas is an essential component of North American energy security. Yet a proposed cap on emissions from the sectors promises to cut Canadian production and exports in the years ahead. It would be hard to provide less environmental benefit for a higher economic and security cost. There are far better ways to reduce emissions while maintaining North America’s security of energy supply.

The high cost of the cap

In 1994 a Liberal federal government, Alberta provincial conservative government and representatives from the oil and gas industry, working together through the national oil sands task force, developed A New Energy Vision for Canada. Their efforts turned what was then a middling resource into a trillion dollar nation-building project. Production has increased tenfold since the report came out.

The task force acknowledged the need for industry to “put its best efforts toward … reducing greenhouse gas emissions.” However, it also expected governments to “understand” that there “is no benefit to Canada or to the environment to have production and value-added processing done outside of the country in less efficient jurisdictions … policies set by regulator must not result in discouraging oil sands production.”

As part of its efforts to meet its climate goals under the Paris Accord, the Canadian government proposed a regulatory framework for an emissions cap on the oil and gas sector in December 2023. It set a legally binding limit on greenhouse gas emissions, targeting a 35 to 38 percent reduction from 2019 levels by 2030 for upstream operations, through regulations to be made under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (CEPA).

The federal government has not yet finalized its proposed regulations. However, industry experts and economists have criticized the current iteration as logistically unworkable, overly expensive, and likely to be challenged as unconstitutional. In effect, this policy layers a cap-and-trade system for just one sector (oil and gas) on top of a competing carbon pricing mechanism (the large-emitter trading systems, often referred to as the industrial carbon price), a discriminatory practice that also undermines the entire economic rationale of a carbon pricing system.

While the Canadian government has maintained that it is focused on reducing emissions rather than production – the latter of which would put it at odds with provincial jurisdiction over non-renewable resources – a series of third party analyses as well as the Parliamentary Budget Office’s own impact assessment find it would indeed constrain Canadian oil and gas production. The economic cost of the emissions cap far exceeds any corresponding benefit in reduced emissions.

How much will the emissions cap cost in terms of dollar per tonne of carbon in avoided emissions, both domestically and globally? Based solely on the cost to the Canadian economy, we estimate the emission cap is equivalent to a C$2,887/tonne carbon price by 2032.

Assuming no impact on global demand and full substitution by non-Canadian crudes, it finds that the cost of each tonne of carbon displaced globally is between C$96,000 to C$289,000 for oil sands bitumen production. For displaced Canadian conventional and natural gas, the cost is infinite, i.e. global emissions would actually be higher for every barrel or unit of Canadian oil and gas displaced with competitor products as a result of the emissions cap.

Canadian oil and gas emissions reduction efforts

The oil and gas sector is the highest emitting economic sector in Canada. However, it has made substantial efforts to reduce emissions over the past two decades and is succeeding. Absolute emissions in the sector peaked in 2014, despite production growing by over a million barrels of oil equivalent since (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Indexed greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (and gross domestic product (GDP) at basic prices, for the oil and gas extraction industry, 2009 to 2022 (2009 = 100). Source: Statistics Canada 2024.

Figure 1 Indexed greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (and gross domestic product (GDP) at basic prices, for the oil and gas extraction industry, 2009 to 2022 (2009 = 100). Source: Statistics Canada 2024.

Much of this success can be attributed to methane capture, particularly in the natural gas and conventional oil sectors, where absolute emissions peaked in 2007 and 2014 respectively.

Since 2014, the oil sands have dramatically increased production by over a million barrels per day, but at the same time have reduced the emissions per barrel every year, leaving the absolute emissions of the oil and gas sector relatively flat. The oil sands are performing well vis-à-vis their international peers, seeing their emissions per barrel decline by 30 percent since 2013, compared to 21 percent for global majors and 34 percent for US E&Ps (exploration and production companies) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Indexed Oil Sands GHG relative intensity trend (2013=100). Source: BMO Capital Markets, “I Want What You Got: Canada’s Oil Resource Advantage,” April 2025

Figure 2 Indexed Oil Sands GHG relative intensity trend (2013=100). Source: BMO Capital Markets, “I Want What You Got: Canada’s Oil Resource Advantage,” April 2025

On an emissions intensity absolute basis, the oil sands have significantly outperformed their peers, shaving off 25kg/barrel of emissions since 2013 (see Figure 3) and more than 65kg/barrel since the oil sands task force wrote their report in 1994.

As emissions improvements from methane reductions plateau, the oil sands are likely to outperform their conventional peers in emissions per barrel reductions going forward. The sector is working on strategies such as solvent extraction and carbon capture and storage that, if implemented, would reduce the life-cycle emissions per barrel of oil sands to levels at or below the global crude average.

Figure 3 Emissions intensity absolute change (kg CO2e/bbl) (2013–24E) Source: BMO Capital Markets, 2025

Figure 3 Emissions intensity absolute change (kg CO2e/bbl) (2013–24E) Source: BMO Capital Markets, 2025

The high cost of the cap

Several parties have analyzed the proposed emissions cap to determine its economic and production impact. The results of the assessments vary widely. For the purposes of this commentary we rely on the federal Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO), which published its analysis of the proposed emissions cap in March 2025. Helpfully, the PBO provided a table summarizing the main findings of the various analyses (see Table 1).

The PBO found that the required reduction in upstream oil and gas sector production levels under an emissions cap would lower real gross domestic product (GDP) in Canada by 0.33 percent in 2030 and 0.39 percent in 2032, and reduce nominal GDP by C$20.5 billion by 2032. The PBO further estimated that achieving the legal upper bound would reduce economy-wide employment in Canada by 40,300 jobs and full-time equivalents by 54,400 in 2032.

Table 2 Comparison of estimated impacts of the proposed emissions cap in 2030. Source: PBO 2025

Table 2 Comparison of estimated impacts of the proposed emissions cap in 2030. Source: PBO 2025

However, the PBO does not estimate the carbon price per tonne of emissions reduced. This is a useful metric as Canadians have become broadly familiar with the real-world impacts of a price on carbon. The federal government quashed the consumer carbon price at $80/tonne in March 2025, ahead of the federal election, due to its unpopularity and perceived impacts on affordability. The federal carbon pricing benchmark is scheduled to hit C$170 in 2030. ECCC has quantified the damages of a tonne of carbon dioxide – referred to as the “Social Cost of Carbon” – as C$294/tonne.

Based on PBO assumptions that the emissions cap will reduce emissions by 7.1MT and reduce GDP by $20.5 billion in 2032, the implied carbon price is C$2,887/tonne.

Emissions cap impact in a global context

Even this eye-popping figure does not tell the full story. The Canadian oil and gas production that must be withdrawn to meet the requirements of the emissions cap will be replaced in global markets from other producers; there is no reason to assume the emissions cap will affect global demand.

Based on life-cycle GHG emissions of the sample of crudes used in the US refinery complex, Canadian oil sands produce only 1 to 3 percent higher emissions than a global average[1] (see Figure 4), with some facilities producing lower emissions than the average barrel.

Figure 4 Life Cycle GHG emissions of crude oils (kg CO2e/bbl). Source: BMO Capital Markets 2025

Figure 4 Life Cycle GHG emissions of crude oils (kg CO2e/bbl). Source: BMO Capital Markets 2025

As such, the emissions cap, if applied just to oil sands production, would only displace global emissions of 71,000 to 213,000 tonnes (1 to 3 percent of 7.1MT). At a cost of C$20.5 billion for those global emissions reductions, the price of carbon is equivalent to C$96,000 to C$289,000 per tonne (see Figure 5).

Figure 5 Cost per tonne of emissions cap behind domestic carbon all (left) and post-global crude substitution (right)

Figure 5 Cost per tonne of emissions cap behind domestic carbon all (left) and post-global crude substitution (right)

For any displaced conventional Canadian crude oil or natural gas, the situation becomes absurd. Because Canadian conventional oil and natural gas have a lower emissions intensity than global averages, global product substitutions resulting from the emissions cap would actually serve to increase global emissions, resulting in an infinite price per tonne of carbon.

The C$100k/tonne carbon price estimate is probably low

We believe our assessment of the effective carbon price of the emissions cap at C$96,000+/tonne to be conservative for the following reasons.

First, it assumes Canadian heavy oil will be displaced in global markets by an average, archetypal crude. In fact, it would be displaced by other heavy crudes from places like Venezuela, Mexico, and Iraq (see Figure 4), which have higher average emissions per barrel than Canadian oil sands crudes. In such a circumstance, global emissions would actually rise and the price per carbon tonne from an emissions cap on oil sands production would also effectively be infinite.

Secondly, emissions cap impact assumptions by the PBO are likely conservative. Those by ECCC, based on a particular scenario outlook, are already outdated. ECCC assumed a production loss of only 0.7 percent by 2030, with oil sands production hitting approximately 3.7 million barrels (MMbbls) per day of bitumen production in 2030. According to S&P Global analysis, that level is likely to be hit this year.[2]

S&P further forecasts oil sands production to reach 4.0 MMbbls by 2030, or about 300,000 barrels more than it produces today. This would represent a far lower production growth rate than the oil sands have experienced in the past five years. But assuming the S&P forecast is correct, production would need to decline in the oil sands by 8 percent to meet the emissions cap requirements. PBO assumed only a 5.4 percent overall oil and gas production loss and ECCC assumed only 0.7 percent, while Conference Board of Canada assumed an 11.1 percent loss and Deloitte assumed 11.5 percent (see Table 1). Production numbers to date more closely align with Conference Board of Canada and Deloitte projections.

Let’s make the Canadian oil and gas sector better, not smaller

The Canadian oil and gas sector, and in particular the oil sands, has a responsibility to do their part to reduce emissions while maintaining competitive businesses that can support good Canadian jobs, provide government revenues and diversify exports. The oil sands sector has re-invested for decades in continuous improvements to drive down production costs while improving its emissions per barrel.

It is hard to conceive of a more expensive and divisive way to reduce emissions from the sector and from the Canadian economy than the proposed emissions cap. Other expensive programs, such as Norway’s EV subsidies, the United Kingdom’s offshore wind contracts-for-difference, Germany’s Energiewende feed-in-tariffs and surcharges, and US Inflation Reduction Act investment tax credits, don’t come close to the high costs of the emissions cap on a price-per-tonne of carbon abated basis.

The emissions cap, as currently proposed, will make Canada’s oil and gas sector significantly less competitive, harm investment, and undermine Canada’s vision to be an energy superpower. This policy will also reduce the oil and gas sector’s capacity to invest in technologies that drive additional emission reductions, such as solvents and carbon capture, especially in our current lower price environment. As such it is more likely to undermine climate action than support it.

The federal and provincial governments have come together to advance a vision for Canadian energy in the past. In this moment, they have the opportunity once again to find real solutions to the climate challenge while harnessing the energy sector to advance Canada’s economic well-being, productivity, and global energy security.

About the author

Heather Exner-Pirot is Director of Energy, Natural Resources, and Environment at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.

Immigration

Mass immigration can cause enormous shifts in local culture, national identity, and community cohesion

By Geoff Russ for Inside Policy

It matters where immigrants come from, why they choose Canada, and how many are arriving from any single country. When it comes to countries of origin, immigration streams into Canada have become wildly unbalanced over the last decade.

Few topics have animated Canadians more than immigration in the past year.

There is broad consensus among the public that the annual intake of newcomers must fall, and polling shows both native-born and immigrant citizens agree on this. In Ottawa, the Conservative opposition has called for lower numbers, and the Liberal government ostensibly concurs.

While much of the discussion surrounding immigration has focused on economic factors like affordability and the shrinking housing supply, less attention has been paid to the cultural and political changes of welcoming more than 5 million people into the country since 2014.

Specifically, attention must be paid to the possible outcomes of importing hundreds of thousands of people from regions embroiled by war or prone to conflict. This is a necessity as digital technology proliferates and guarantees the world will be interconnected, but not united.

Mass immigration brings in far more than just people. It can cause enormous shifts in local culture, national identity, political allegiances, and community cohesion.

It matters where immigrants come from, why they choose Canada, and how many are arriving from any single country. When it comes to countries of origin, immigration streams into Canada have become wildly unbalanced over the last decade.

In 2023, almost 140,000 people immigrated to Canada from India, while the second-largest intake came from China, with 31,770 people.

This new trend is at odds with Canada’s historical immigration policies, which were more evenly weighted by country. In 2010, the top three national pools of immigration were the Philippines at 38,300 newcomers, India with 33,500, and China with 31,800.

Other countries that Canada has received increasing numbers of migrants from includes Syria, Pakistan, and Nigeria.

Past federal governments took consideration for details like economic needs and capacity for integration. Canadian immigration policy in 2025 should take into account modern communications and conflicts within certain regions as well.

21st century technology continues to advance and innovate at dizzying speeds, giving rise to immersive social platforms and instant messaging platforms like WhatsApp or Signal. This has brought the world closer together, but rather than promoting peace and understanding, it has amplified foreign conflicts and brought them to our own backyards.

Tens of thousands of migrants from the Levant have arrived since 2015, a region where anti-Zionism is deeply ingrained in the cultures, as well as full-blown antisemitism.

Since the outbreak of the Israel-Hamas War in 2023, the entire West has borne witness to antisemitic violence in Europe and North America, often perpetrated by ideologically motivated migrants.

Earlier this year, a Syrian migrant in Germany went on a stabbing spree with the intent of murdering Jews, while last September, Canadian police foiled the plot of a Pakistani man in Ontario who had planned to commit a mass killing of Jews in New York City.

Canada’s political culture has been profoundly affected by these same waves, with demographic changes forcing the federal government to alter its longstanding foreign policy positions. For example, the newly-minted Minister of Industry Mélanie Joly allegedly remarked last year that her shifting stance on the Israel-Hamas war was due to the “demographics” of her Montreal riding.

Montreal itself has become a hotbed of anti-Israeli and anti-semitic violence. Riots, property damage, and the storming of the McGill University campus have been carried out by radicals inspired by Hamas and their allies.

In 1968, the great Canadian thinker Marshall McLuhan co-authored War and Peace in the Global Village, which warned of the consequences of modern technologies erasing the boundaries of the world. McLuhan explicitly cautioned that technology would make the world smaller, and lead to conflict in his theorized global village.

Today, that village is one where Jewish students are routinely harassed on college campuses in Vancouver and Toronto, while synagogues are burnt to the ground in Melbourne. It does not matter whether the victims are Israeli or not. They are seen by their assailants as legitimate targets as part of an enemy tribe.

On May 21, two staffers at the Israeli embassy in Washington DC were shot dead by a man shouting pro-Palestinian slogans.

These sorts of imported feuds go beyond the Middle East. Global tensions in regions like the Indian subcontinent present another threat of foreign-inspired and funded violence, as well as undue political shifts.

India and Pakistan are locked in a long running standoff over the disputed territory of Kashmir.

Last month, several tourists were murdered in Kashmir by militants that India accused Pakistan of backing, leading to several low-level exchanges between the Indian and Pakistani militaries before a ceasefire was brokered. Tensions are far from dissipated, and the possibility of a full-scale confrontation between India and Pakistan remains high.

Considering those two rivals have massive diasporas in the West, a potential war on the subcontinent could radically change domestic politics in countries in Canada, Australia, and Britain.

In 2022, violent clashes broke out between Hindu and Muslim youths in the British city of Leicester following a cricket match between India and Pakistan. The street battles lasted for weeks, and threatened to restart later that year following an escalation in India and Pakistan’s clash over Kashmir. In London, demonstrators from the Pakistani and Indian communities came close to violence.

If a sporting rivalry can inspire hooliganism, a war will spark something far worse, and the globalization of the Israel-Gaza conflict is a glimpse into what that might look like.

There is historical precedent in Canada for how overseas conflicts affect domestic politics.

During the 19th century, hundreds of thousands of Irish—both Catholic and Protestant—emigrated to Canada before and after Confederation in 1867. They brought their religious feuds with them.

The militantly anti-Catholic Orange Order, run by Protestants, became one of the most powerful political forces in Ontario. They held a virtual monopoly on municipal politics in Toronto, excluded Catholics from jobs in the public service, and took part in brawls with the city’s Irish Catholic community for more than 100 years.

Thomas D’Arcy McGee, one of the Fathers of Confederation and an Irish Catholic migrant, was murdered for speaking out against the republican Fenian Brotherhood, which had infiltrated politics both in Canada and the United States.

Integration throughout successive generations mitigates and even practically eliminates the impact of imported conflicts. This was the case with the Irish sectarian divide, though it took over a century to fade away.

Worth noting is that roughly 300,000 Ukrainian refugees currently reside in Canada, having been admitted under a special visa program following the Russian invasion in 2022. It is intended to be temporary, with the expectation of repatriation once a stable peace returns to Ukraine.

Similarly to Irish-Canadians, the vast majority of the established Ukrainian-Canadian community has its roots in pre-modern Canada, and is largely well-integrated into the country’s social fabric. To date, there has been no major violence or anti-social harms inflicted upon their Russian-Canadian counterparts despite the war, or vice-versa.

Furthermore, the Canadian government has a longstanding close relationship with Kyiv, and there is far more trust and transparency regarding intent and collaboration. This is not the case with governments like China and India, the former of whom actively interferes in our elections, and the latter of which has been accused of assassinating dissidents on Canadian soil.

The existence of the iPhone, the internet, and opportunistic foreign governments makes it incredibly dangerous to not change course. That is not to imply that the average migrant is an active foreign agent. But the sheer quantity makes vetting them all a challenge.

Mitigating these threats requires strategic planning when crafting immigration policy.

Other parts of the world like Southeast Asia, Southern Europe, and Latin America are relatively stable and peaceful and are potential sources of newcomers with far lower risk of foreign interference and diasporic violence.

At-play is the stability, unity, and integrity of our political system. Canadian politics must remain fully Canadian in its focus and priorities. That cannot happen if we sleepwalk into becoming a battleground for the rest of the world.

Geoff Russ is a writer and policy analyst, and a contributor for the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.

-

Carbon Tax2 days ago

Carbon Tax2 days agoCanada’s Carbon Tax Is A Disaster For Our Economy And Oil Industry

-

Disaster2 days ago

Disaster2 days agoTexas flood kills 43 including children at Christian camp

-

Daily Caller2 days ago

Daily Caller2 days agoTrump’s One Big Beautiful Bill Resets The Energy Policy Playing Field

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoAlberta Next: Immigration

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoThe Digital Services Tax Q&A: “It was going to be complicated and messy”

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoElon Musk forms America Party after split with Trump

-

Crime14 hours ago

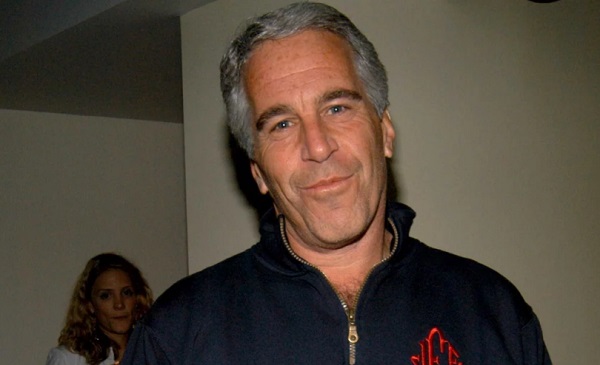

Crime14 hours agoNews Jeffrey Epstein did not have a client list, nor did he kill himself, Trump DOJ, FBI claim

-

COVID-1912 hours ago

COVID-1912 hours agoFDA requires new warning on mRNA COVID shots due to heart damage in young men