Housing

Trudeau admits immigration too much for Canada to ‘absorb’ but keeps target at record high

From LifeSiteNews

Despite his admission that the influx of people has outpaced Canada’s ability to sustain itself, Trudeau said he is committed to continuing his government’s plan to bring in 500,000 permanent immigrants each year.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau has admitted that his mass immigration policies have driven Canadians’ wages down and attributed to the housing crisis, but he still insists on bringing in hundreds of thousands of people each year.

During an April 2 media conference in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, Trudeau acknowledged that his immigration policies have negatively affected Canadians after a journalist questioned him on how his policies have contributed to record high unaffordability in the nation.

“Over the past few years, we’ve seen a massive spike in temporary immigration, whether it’s temporary foreign workers or whether it’s international students in particular that have grown at a rate far beyond what Canada has been able to absorb,” he admitted.

PM Trudeau says immigration to Canada has "grown at a rate far beyond what Canada has been able to absorb," adding that "temporary immigration has caused so much pressure in our communities," in relation to housing #cdnpoli pic.twitter.com/3ASFufZKID

— Mackenzie Gray (@Gray_Mackenzie) April 2, 2024

“To give an example, in 2017, two per cent of Canada’s population was made up of temporary immigrants,” Trudeau continued. “Now we’re at 7.5 per cent of our population comprised of temporary immigrants. That’s something we need to get back under control.”

Amid heckling from protestors, Trudeau acknowledged that the immigration crisis must be solved. However, he attributed the negative effects only to the spike in “temporary” immigrants, who he claims are “putting pressure on our communities.”

“That’s something that we need to get back under control, both for the benefit of those people because international students we’re seeing increasingly vulnerable to mental health challenges, to not being able to thrive and get the education they want,” he stated.

“But also, increasingly more and more businesses [are] relying on temporary foreign workers in a way that is driving down wages in some sectors,” Trudeau continued.

Despite the admission, Trudeau announced that he still plans to bring in permanent immigrants at a record pace, despite Canadians struggling to afford homes and even food.

“Every year, we bring in about 450,000, now close to 500,000, permanent residents a year, and that is part of the necessary growth of Canada,” he insisted. “It benefits our citizens, our communities, it benefits our economy.”

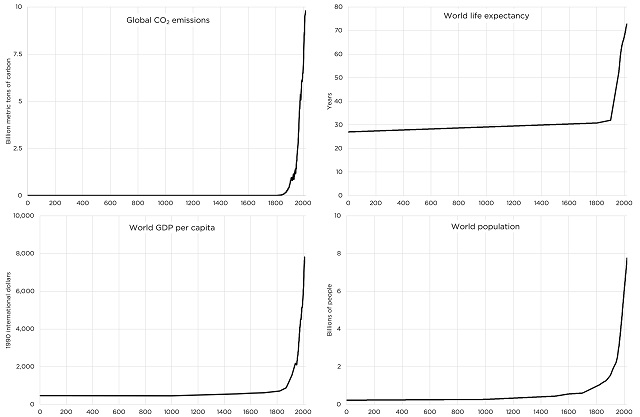

While Trudeau remains insistent that mass immigration “benefits” the economy, recent figures show that the nation’s GDP per capita growth rate is dismal compared to other countries with lower relative immigration levels like the United States.

The Bank of Canada has even gone as far as saying that the weakening productivity of the nation’s economy has become “an emergency.”

In March, Canada reached a population of 41 million, just 9 months after hitting the 40 million mark. Such growth is unprecedented in recent history and among the highest immigration rates in the world.

Trudeau’s acknowledgment comes as a recent report found that Canada is one of the unhappiest places in the West for people in their 20s as young Canadians are experiencing the effects of Trudeau’s government, which has been criticized for its overspending, onerous climate regulations, lax immigration policies, and “woke” politics.

Additionally, a March poll revealed that seven out of 10 Canadians believe the country is broken and that the Trudeau government does not focus on issues that matter.

Furthermore, many have pointed out that considering rising home prices, many Canadians under 30 are at risk of never being able to purchase a home.

Housing

Trudeau’s 2024 budget could drive out investment as housing bubble continues

From LifeSiteNews

By David James

The extent to which the Canadian economy is distorted by a property bubble can be seen by comparing government debt with household debt, with the latter being 130 percent of GDP, nearly twice as much as American households.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s federal government has brought in its 2024 budget, which projects C$53 billion in new spending over the next 5 years. It includes a significant capital gains tax increase, which some are warning will drive away investment, and a plan for more government-controlled public housing.

The Trudeau government is wrestling with a problem that is afflicting most English-speaking economies: how to deal with the consequences of a 20-year house price bubble that has led to deep social divisions, especially between baby boomers and people under 40.

House prices have tripled over the last 20 years on average, fuelled by the combination of aggressive bank lending and, until recently, falling interest rates. Neither is directly controlled by the federal government. There is no avenue to restrict how much banks lend and the Bank of Canada sets interest rates independently.

Accordingly, the Trudeau government is left to tinker at the edges. It will legislate an increase, from one half to two-thirds, in the share of capital gains subject to taxation for annual investment profits greater than C$250,000. The change will apply to individuals, companies and trusts.

Christina Freeland, Canada’s minister for finance, claimed improbably that only 0.13 percent of Canadians with an average income of $1.42 million are expected to pay more income tax on their capital gains in any given year.

That is a dubious forecast. The average house price in Canada 20 years ago was C$241,000; it is now C$719,000. Any Canadians who bought an investment property (family homes are exempt) before about 2015 are likely to have a capital gain larger than C$250,000 should they sell.

The government’s claim that the change will only affect a tiny proportion of Canada’s population is also belied by the government’s own forecast that the tax change will raise over C$20 billion over five years.

The extent to which the Canadian economy is distorted by a property bubble can be seen by comparing government debt with household debt. Canada’s government debt is fairly modest by current international standards: 67.8 percent of GDP in March 2023, down from 73 percent in the previous year. That is about half the U.S. government debt and half the average for G7 countries.

Canada’s budget deficit is also cautious by Western standards. In 2023-24 it was C$40 billion, equivalent to 1.4 percent of GDP. The U.S. budget deficit is currently over 6 percent of GDP.

By contrast Canada’s household debt, inflated by large mortgages, is at over 130 percent of GDP, making borrowers vulnerable to rising interest rates. U.S. household debt is about 75 percent of GDP. Attracted by rising house prices and the advantages of negative gearing (deducting rental losses from a property investment from income tax), Canadians have seen property as their preferred investment option.

Investors account for 30 percent of home buying in Canada, and about one in five properties is owned by an investor. Worse, the enthusiasm for property investment seems to be intensifying. According to one survey, 23 percent of Canadians who do not own a residential investment property say that they are likely to purchase one in the next five years, and 51 percent of current investors say that they are likely to purchase an additional residential investment property within the same time frame.

The problem with the bias towards property investment is that it is actually a punt on land values – and land is inherently unproductive. Business groups have criticized the government’s capital gains hike as a disincentive for investment and innovation, but the far bigger issue is investors’ focus on property, which is crowding out interest in other kinds of investments.

That means the main source investment capital for businesses will tend to come from institutions, such as mutual funds, which typically have a global, rather than local, orientation.

Faced with forces largely out of its control, the Trudeau government is fiddling at the edges. It has announced the introduction of what it calls “Canada’s Housing Plan”, which is aimed at unlocking over 3.8 million homes by 2031. Two million are expected to be new homes, with the government contributing to more than half of them. This will be done by converting underused federal offices into homes, building homes on Canada Post properties, redeveloping National Defence lands, creating more loans for building apartments in Ottawa, and looking at taxing vacant land.

The initiatives may have some effect on supply and demand, but the property price excesses are mainly a financial problem caused by unrestrained bank lending that has been fuelled by low interest rates. When a correction does occur, it will most likely be because of changed global financial conditions, not government policy or fiscal changes.

There are other measures that could be taken to address the property bubble such as reducing, or removing, negative gearing or more heavily taxing capital gains only on property but not other types of investments. But these policies would no doubt would be politically unsalable, so the Trudeau government is instead making minor changes, probably hoping that the problem will fix itself.

Frontier Centre for Public Policy

The Smallwood solution

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

All Canadians deserve decent housing, and indigenous people have exactly the same legal right to house ownership, or home rental, as any other Canadian. That legal right is zero.

$875,000 for every indigenous man, woman and child living in a rural First Nations community. That is approximately what Canadian taxpayers will have to pay if a report commissioned by the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) is accepted. According to the report 349 billion dollars is needed to provide the housing and infrastructure required for the approximately 400,000 status Indians still living in Canada’s 635 or so First Nations communities. ($349,000,000,000 divided by 400,000 = ~$875,000).

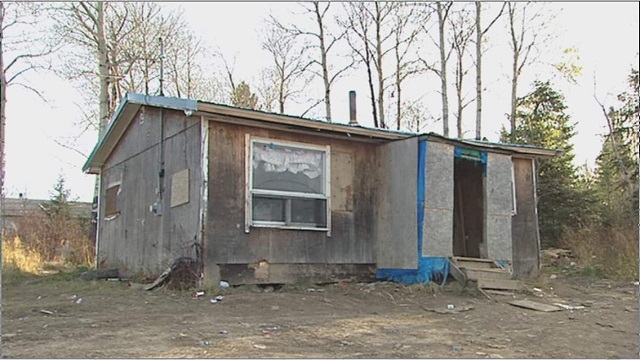

St Theresa Point First Nation is typical of many of such communities. It is a remote First Nation community in northern Manitoba. CBC recently did a story about it. One person interviewed was Christina Wood, who lives in a deteriorating house with 23 family members. Most other people in the community live in similar squalor. Nobody in the community has purchased their own house, and all rely on the federal government to provide housing for them. Few people in the community have paid employment. Those that do have salaries that come in one way or another from the taxpayer.

But St. Theresa Point is a growing community in the sense that birth rates are high, and few people have the skills or motivation needed to be successfully employed in Winnipeg, or other job centres. Social pathologies, such as alcohol and other drug addictions are rampant in the community. Suicide rates are high.

St. Theresa Point is one of hundreds of such indigenous communities in Canada. This is not to say that all such First Nations communities are poor. In fact, some are wealthy. Those lucky enough to be located in or near Vancouver, for example, located next to oil and gas, or on a diamond mine do very well. Some, like Chief Clarence Louis’ Osoyoos community have successfully taken advantage of geography and opportunity and created successful places where employed residents live rich lives.

Unfortunately, most are not like that. They look a lot more like St. Theresa Point. And the AFN now says that 350 billion dollars are needed to keep those communities going.

Meanwhile, all of Canada is in the grip of a serious housing crisis. There are many causes for this, including the massive increase in new immigrants, foreign students and asylum seekers, all of whom have to live somewhere. There are various proposals being considered to respond to this problem. None of those plans come anywhere near to suggesting that $875,000 of public funds should be spent on every Canadian man, woman or child who needs housing. The public treasury would not sustain such an assault.

All Canadians deserve decent housing, and indigenous people have exactly the same legal right to house ownership, or home rental, as any other Canadian. That legal right is zero. Our constitution does not give Canadians – indigenous or non-indigenous- any legal right to publicly funded home ownership, or any right to publicly funded rental property. And no treaty even mentions housing. In all cases it is assumed that Canadians – indigenous and non-indigenous – will provide for themselves. This is the brutal reality. We are on our own when it comes to housing. There are government programs that assist low income people to buy or rent homes, but they are quite limited, and depend on a person qualifying in various ways.

But indigenous people do not have any preferred right to housing. The chiefs and treaty commissioners who signed the treaties expected indigenous people to provide for their own housing in exactly the same way that all other Canadians were expected to provide for their own housing. In fact, the treaty makers, chiefs and treaty commissioners – assumed that indigenous people would support themselves just like every other Canadian. There was no such thing as welfare then.

Our leaders today face difficult decisions about how to spend limited public funds to try and help struggling Canadians find adequate housing in which to raise their families, and get to and from their places of employment. Indigenous Canadians deserve exactly as much help in this regard as everyone else. Finding sensible, affordable ways to do this is vitally important if Canada is to thrive.

And one of hundreds of these difficult and expensive housing decisions our leaders must deal with now is how to respond to this new demand for 350 billion dollars – a demand that would result in indigenous Canadians receiving hundreds of times more housing help than other Canadians.

Our leaders know that authorising massive spending like that in uneconomic communities is completely unfair to other Canadians – for one thing doing so means that there would be no money left for urban housing assistance. They also know that pouring massive amounts of money into uneconomic, dysfunctional communities like St. Theresa’s Point – the “unguarded concentration camps” Farley Mowat described long ago- only keeps generations of young indigenous people locked in hopeless dependency.

In short, they know that the 350 billion dollar demand makes no sense.

Our leaders know that, but they won’t say that. In fact it is not hard to predict how politicians will respond to the 350 billion dollar demand. None of their responses will look even remotely like what I have written above. Instead, they will say soothing things, while pushing the enormous problem down the road. Eventually, when forced by circumstances to actually make spending decisions they will provide stopgap “bandage” funding. And perhaps come up with pretend “loan guarantee” schemes – loans they know will never be repaid. Massive loan defaults in the future will be an enormous problem for our children and grandchildren. But today’s leaders will be gone by then.

So, in a decade or so communities, like St. Theresa Point, will still be there. Any new housing that has been built will already be deteriorating and inadequate. The communities will remain dependent. The young people will be trapped in hopeless dependency.

And the chiefs will be making new money demands.

At some point this country will have to confront the reality that most of Canada’s First Nations reserves, particularly the remote ones, are not sustainable. Better plans to educate and provide job skills to the younger generations in those communities, and assist them to move to job centres, will have to be found. Continuing to pretend that this massive problem will sort itself out by passing UNDRIP legislation, or pretending that those depressed communities are “nations” is only delaying the inevitable.

When Joey Smallwood told the Newfoundland fishermen, who had lived in their outports for generations, that they must move for their own good, there was much pain. But the communities could no longer support themselves, and it had to be done. Entire communities moved. It worked out.

The northern First Nations communities are no different. The ancestors of the residents of those communities supported themselves by fishing and hunting. It was an honourable life. But it is gone. The young people there now will have to move, build new lives, and become self-supporting like their ancestors.

Brian Giesbrecht, retired judge, is a Senior Fellow at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

-

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days ago

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days agoCome For The Graduate Studies, Stay For The Revolution

-

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days ago

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days agoJordan Peterson, Canadian lawyer warn of ‘totalitarian’ impact of Trudeau’s ‘Online Harms’ bill

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoFormer senior financial advisor charged with embezzling millions from Red Deer area residents

-

Brownstone Institute1 day ago

Brownstone Institute1 day agoThe Teams Are Set for World War III

-

Frontier Centre for Public Policy1 day ago

Frontier Centre for Public Policy1 day agoBudget 2024 as the eve of 1984 in Canada

-

COVID-191 day ago

COVID-191 day agoPfizer reportedly withheld presence of cancer-linked DNA in COVID jabs from FDA, Health Canada

-

National1 day ago

National1 day agoAnger towards Trudeau government reaches new high among Canadians: poll

-

COVID-1920 hours ago

COVID-1920 hours agoTrudeau gov’t has paid out over $500k to employees denied COVID vaccine mandate exemptions