MacDonald Laurier Institute

The (one hundred) million dollar question – What is a journalist?: Peter Menzies

From the MacDonald Laurier Institute

By Peter Menzies

What the reaction to David Menzies’ arrest tells us about the profession in Canada

The best part about the RCMP’s recent street mugging of David (aka the Menzoid) Menzies was neither the uproar over the arrest nor the boost it provided to Rebel News’ bottom line.

Nope. The really giggly, wincey, cringeworthy part was the huffy offence taken by so many in the legacy media after Menzies was referred to as one of them—a journalist—and by no less an influencer than the leader of His Majesty’s Loyal Opposition.

“We’re going to stop arresting journalists,” said Conservative Leader Pierre Poilievre, referring to L’affaire Menzoid. “It’s outrageous for the prime minister and his government to have journalists arrested merely for asking questions of ministers and public officials.”

Thus was the cat thrown among the pigeons. Boy, did they flutter.

Globe and Mail columnist Shannon Proudfoot described Rebel News’ (standard) response to the matter—a fundraiser—as having more in common with “busking” than journalism.

CBC and its, at times, pompous panels referred to Menzies (no relation) as either a Rebel News “employee” or “personality,” as did Global News. National Post called him a “commentator.” One CBC reference to Menzies apparently presented him as someone who “self-identified” as a journalist, as if it was an orientation.

None of those are inaccurate. But all ensured no linkage between Menzies and the J-word, a metier to which media may assign a higher social rank than the one assumed by the public.

In case you missed it, Menzies was attempting to get a quote from Deputy Prime Minister Chrystia Freeland regarding the government’s hesitance to designate Iran’s Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps as a terrorist organization. He approached her on the street in standard fashion and then her security officer set a pick which resulted in a mild collision of shoulders between himself and Menzies. The officer thuggishly pushed Menzies against a wall and arrested him for assault. The pride of Rebel News was then handcuffed and driven from the scene only to be quickly released without charge.

Many were outraged. But there was also a cohort that justified it all because Menzies, they said, is not a “real journalist.”

Some went so far as to suggest the formation of some sort of accreditation body to decide who should be deemed qualified to report on current affairs. None seemed to realize the government has already appointed one, albeit to determine who qualifies for its loot.

These displays of ill-informed hubris were not well-received by many independents practicing freedom of the press without government approval as qualified Canadian journalism organizations.

“Mainstream media is arrogant enough to define who is a journalist while their audience shrinks to nothing while alternative media like Rebel and Western Standard explode,” grumbled a former newspaper colleague now enjoying success as an unaligned online reporter. “Many journalists now working with so-called alternative media have way more experience in the industry than those working now in the dying mainstream.”

Let’s be clear: journalism is not a profession. Read it again. Journalism is not a profession.

It is a trade, or a craft, requiring no more than two semesters of post-secondary study followed by years of apprenticeship.

Yes, universities may have turned it into an over-priced paper chase but a quick look at most courses makes it clear a profound intellect is not a prerequisite.

The greatest skill traditionally required (and it is one often abandoned due to its difficulty) involves the ability to set aside one’s own biases, eschew all assumptions, and produce truly objective work that explores all sides of issues and events.

These days, though, not everyone subscribes to that, which means we have two very broad classes of news organizations.

One is composed of those who aspire to tell stories through the lens of objectivity. For them, the pursuit of journalism is an end in itself. It is also the practice in greatest alignment with what most reader surveys indicate is how the public wishes to be served. I call these people journalists because they toil thanklessly to reveal truths that challenge preconceptions and leave decisions concerning what to think about matters up to the reader/viewer/listener.

The other is best described as agenda journalism. Those involved in this far more romantic sphere tend to see journalism as the means towards an end, whether it be social justice, free markets, environmentalism, or Palestine—pick a cause and there’s a crusader at the ready, laptop and camera in hand.

I call these people storytellers. They certainly have their fans, many of whom believe them to be true journalists because they show them the world through a lens they find agreeable.

Within those categories—both of which contribute to the explosion of voices now available—there are a number of roles. The BBC website contains a comprehensive overview.

For instance, in print, “A reporter writes stories on a range of topics including news, politics, sports, culture and entertainment. Some are correspondents which means they specialize in a field, such as sport, health, crime, business or education. Others are feature writers who cover topics in more depth or write human-interest stories.”

While in broadcast, “A presenter is the voice (radio) or face (TV) of the show. He or she welcomes the audience to the show, interviews guests, reads news, shares information, reads off autocues, and prompts audience participation.”

This is so straightforward that, were it not for the fact Canada’s media are currently squabbling over who gets what funds provided by the government, it would be difficult to understand why it matters who gets to be called a journalist.

Herein lies the inherent challenge of government intervention in the news media. If the sector was left to market forces, then consumers would decide who and what constitutes journalism. But as soon as the government established its policy regime to support the sector, it needed to set parameters to determine eligibility. It needed, in other words, to put itself directly in the business of adjudicating who is a journalist. The Menzies episode (including the mainstream media reaction) demonstrates why this is such a bad idea.

Whether the entrenched players like it or not, surely a journalist is anyone with the capability and inclination to uncover and honestly distribute the news, information, and stories the public has a right to know.

Little wonder those begging loudest for seats in the financial lifeboats are the ones most desperate to declare their virtue and lay exclusive claim to the title.

Peter Menzies is a Senior Fellow with the Macdonald-Laurier Institute, a former newspaper executive, and past vice chair of the CRTC.

Alberta

High costs, low returns – Canada’s wildly expensive emissions cap

In this new commentary, Director of Energy, Natural Resources, and Environment Heather Exner-Pirot reveals why the Canadian government’s oil and gas emissions cap isn’t just expensive – it’s economic insanity.

Canada is the world’s third-largest exporter of oil, fourth-largest producer, and top source of imports to the United States. Much of Canada’s oil wealth is concentrated in the oil sands in northern Alberta, which hosts 99 percent of the country’s enormous oil endowment: about 160 billion barrels of proven reserves, of a total resource of approximately 1.8 trillion barrels. This is the major source of oil to the United States refinery complex, a large part of which is optimized for the oil sands’ heavy oil.

Reliability of energy supply has remerged as a major geopolitical issue. Canadian oil and gas is an essential component of North American energy security. Yet a proposed cap on emissions from the sectors promises to cut Canadian production and exports in the years ahead. It would be hard to provide less environmental benefit for a higher economic and security cost. There are far better ways to reduce emissions while maintaining North America’s security of energy supply.

The high cost of the cap

In 1994 a Liberal federal government, Alberta provincial conservative government and representatives from the oil and gas industry, working together through the national oil sands task force, developed A New Energy Vision for Canada. Their efforts turned what was then a middling resource into a trillion dollar nation-building project. Production has increased tenfold since the report came out.

The task force acknowledged the need for industry to “put its best efforts toward … reducing greenhouse gas emissions.” However, it also expected governments to “understand” that there “is no benefit to Canada or to the environment to have production and value-added processing done outside of the country in less efficient jurisdictions … policies set by regulator must not result in discouraging oil sands production.”

As part of its efforts to meet its climate goals under the Paris Accord, the Canadian government proposed a regulatory framework for an emissions cap on the oil and gas sector in December 2023. It set a legally binding limit on greenhouse gas emissions, targeting a 35 to 38 percent reduction from 2019 levels by 2030 for upstream operations, through regulations to be made under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (CEPA).

The federal government has not yet finalized its proposed regulations. However, industry experts and economists have criticized the current iteration as logistically unworkable, overly expensive, and likely to be challenged as unconstitutional. In effect, this policy layers a cap-and-trade system for just one sector (oil and gas) on top of a competing carbon pricing mechanism (the large-emitter trading systems, often referred to as the industrial carbon price), a discriminatory practice that also undermines the entire economic rationale of a carbon pricing system.

While the Canadian government has maintained that it is focused on reducing emissions rather than production – the latter of which would put it at odds with provincial jurisdiction over non-renewable resources – a series of third party analyses as well as the Parliamentary Budget Office’s own impact assessment find it would indeed constrain Canadian oil and gas production. The economic cost of the emissions cap far exceeds any corresponding benefit in reduced emissions.

How much will the emissions cap cost in terms of dollar per tonne of carbon in avoided emissions, both domestically and globally? Based solely on the cost to the Canadian economy, we estimate the emission cap is equivalent to a C$2,887/tonne carbon price by 2032.

Assuming no impact on global demand and full substitution by non-Canadian crudes, it finds that the cost of each tonne of carbon displaced globally is between C$96,000 to C$289,000 for oil sands bitumen production. For displaced Canadian conventional and natural gas, the cost is infinite, i.e. global emissions would actually be higher for every barrel or unit of Canadian oil and gas displaced with competitor products as a result of the emissions cap.

Canadian oil and gas emissions reduction efforts

The oil and gas sector is the highest emitting economic sector in Canada. However, it has made substantial efforts to reduce emissions over the past two decades and is succeeding. Absolute emissions in the sector peaked in 2014, despite production growing by over a million barrels of oil equivalent since (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Indexed greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (and gross domestic product (GDP) at basic prices, for the oil and gas extraction industry, 2009 to 2022 (2009 = 100). Source: Statistics Canada 2024.

Figure 1 Indexed greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (and gross domestic product (GDP) at basic prices, for the oil and gas extraction industry, 2009 to 2022 (2009 = 100). Source: Statistics Canada 2024.

Much of this success can be attributed to methane capture, particularly in the natural gas and conventional oil sectors, where absolute emissions peaked in 2007 and 2014 respectively.

Since 2014, the oil sands have dramatically increased production by over a million barrels per day, but at the same time have reduced the emissions per barrel every year, leaving the absolute emissions of the oil and gas sector relatively flat. The oil sands are performing well vis-à-vis their international peers, seeing their emissions per barrel decline by 30 percent since 2013, compared to 21 percent for global majors and 34 percent for US E&Ps (exploration and production companies) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Indexed Oil Sands GHG relative intensity trend (2013=100). Source: BMO Capital Markets, “I Want What You Got: Canada’s Oil Resource Advantage,” April 2025

Figure 2 Indexed Oil Sands GHG relative intensity trend (2013=100). Source: BMO Capital Markets, “I Want What You Got: Canada’s Oil Resource Advantage,” April 2025

On an emissions intensity absolute basis, the oil sands have significantly outperformed their peers, shaving off 25kg/barrel of emissions since 2013 (see Figure 3) and more than 65kg/barrel since the oil sands task force wrote their report in 1994.

As emissions improvements from methane reductions plateau, the oil sands are likely to outperform their conventional peers in emissions per barrel reductions going forward. The sector is working on strategies such as solvent extraction and carbon capture and storage that, if implemented, would reduce the life-cycle emissions per barrel of oil sands to levels at or below the global crude average.

Figure 3 Emissions intensity absolute change (kg CO2e/bbl) (2013–24E) Source: BMO Capital Markets, 2025

Figure 3 Emissions intensity absolute change (kg CO2e/bbl) (2013–24E) Source: BMO Capital Markets, 2025

The high cost of the cap

Several parties have analyzed the proposed emissions cap to determine its economic and production impact. The results of the assessments vary widely. For the purposes of this commentary we rely on the federal Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO), which published its analysis of the proposed emissions cap in March 2025. Helpfully, the PBO provided a table summarizing the main findings of the various analyses (see Table 1).

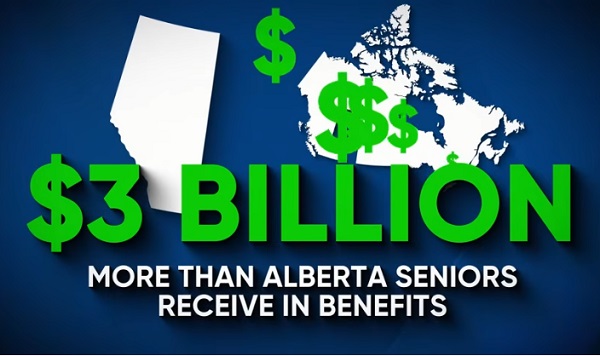

The PBO found that the required reduction in upstream oil and gas sector production levels under an emissions cap would lower real gross domestic product (GDP) in Canada by 0.33 percent in 2030 and 0.39 percent in 2032, and reduce nominal GDP by C$20.5 billion by 2032. The PBO further estimated that achieving the legal upper bound would reduce economy-wide employment in Canada by 40,300 jobs and full-time equivalents by 54,400 in 2032.

Table 2 Comparison of estimated impacts of the proposed emissions cap in 2030. Source: PBO 2025

Table 2 Comparison of estimated impacts of the proposed emissions cap in 2030. Source: PBO 2025

However, the PBO does not estimate the carbon price per tonne of emissions reduced. This is a useful metric as Canadians have become broadly familiar with the real-world impacts of a price on carbon. The federal government quashed the consumer carbon price at $80/tonne in March 2025, ahead of the federal election, due to its unpopularity and perceived impacts on affordability. The federal carbon pricing benchmark is scheduled to hit C$170 in 2030. ECCC has quantified the damages of a tonne of carbon dioxide – referred to as the “Social Cost of Carbon” – as C$294/tonne.

Based on PBO assumptions that the emissions cap will reduce emissions by 7.1MT and reduce GDP by $20.5 billion in 2032, the implied carbon price is C$2,887/tonne.

Emissions cap impact in a global context

Even this eye-popping figure does not tell the full story. The Canadian oil and gas production that must be withdrawn to meet the requirements of the emissions cap will be replaced in global markets from other producers; there is no reason to assume the emissions cap will affect global demand.

Based on life-cycle GHG emissions of the sample of crudes used in the US refinery complex, Canadian oil sands produce only 1 to 3 percent higher emissions than a global average[1] (see Figure 4), with some facilities producing lower emissions than the average barrel.

Figure 4 Life Cycle GHG emissions of crude oils (kg CO2e/bbl). Source: BMO Capital Markets 2025

Figure 4 Life Cycle GHG emissions of crude oils (kg CO2e/bbl). Source: BMO Capital Markets 2025

As such, the emissions cap, if applied just to oil sands production, would only displace global emissions of 71,000 to 213,000 tonnes (1 to 3 percent of 7.1MT). At a cost of C$20.5 billion for those global emissions reductions, the price of carbon is equivalent to C$96,000 to C$289,000 per tonne (see Figure 5).

Figure 5 Cost per tonne of emissions cap behind domestic carbon all (left) and post-global crude substitution (right)

Figure 5 Cost per tonne of emissions cap behind domestic carbon all (left) and post-global crude substitution (right)

For any displaced conventional Canadian crude oil or natural gas, the situation becomes absurd. Because Canadian conventional oil and natural gas have a lower emissions intensity than global averages, global product substitutions resulting from the emissions cap would actually serve to increase global emissions, resulting in an infinite price per tonne of carbon.

The C$100k/tonne carbon price estimate is probably low

We believe our assessment of the effective carbon price of the emissions cap at C$96,000+/tonne to be conservative for the following reasons.

First, it assumes Canadian heavy oil will be displaced in global markets by an average, archetypal crude. In fact, it would be displaced by other heavy crudes from places like Venezuela, Mexico, and Iraq (see Figure 4), which have higher average emissions per barrel than Canadian oil sands crudes. In such a circumstance, global emissions would actually rise and the price per carbon tonne from an emissions cap on oil sands production would also effectively be infinite.

Secondly, emissions cap impact assumptions by the PBO are likely conservative. Those by ECCC, based on a particular scenario outlook, are already outdated. ECCC assumed a production loss of only 0.7 percent by 2030, with oil sands production hitting approximately 3.7 million barrels (MMbbls) per day of bitumen production in 2030. According to S&P Global analysis, that level is likely to be hit this year.[2]

S&P further forecasts oil sands production to reach 4.0 MMbbls by 2030, or about 300,000 barrels more than it produces today. This would represent a far lower production growth rate than the oil sands have experienced in the past five years. But assuming the S&P forecast is correct, production would need to decline in the oil sands by 8 percent to meet the emissions cap requirements. PBO assumed only a 5.4 percent overall oil and gas production loss and ECCC assumed only 0.7 percent, while Conference Board of Canada assumed an 11.1 percent loss and Deloitte assumed 11.5 percent (see Table 1). Production numbers to date more closely align with Conference Board of Canada and Deloitte projections.

Let’s make the Canadian oil and gas sector better, not smaller

The Canadian oil and gas sector, and in particular the oil sands, has a responsibility to do their part to reduce emissions while maintaining competitive businesses that can support good Canadian jobs, provide government revenues and diversify exports. The oil sands sector has re-invested for decades in continuous improvements to drive down production costs while improving its emissions per barrel.

It is hard to conceive of a more expensive and divisive way to reduce emissions from the sector and from the Canadian economy than the proposed emissions cap. Other expensive programs, such as Norway’s EV subsidies, the United Kingdom’s offshore wind contracts-for-difference, Germany’s Energiewende feed-in-tariffs and surcharges, and US Inflation Reduction Act investment tax credits, don’t come close to the high costs of the emissions cap on a price-per-tonne of carbon abated basis.

The emissions cap, as currently proposed, will make Canada’s oil and gas sector significantly less competitive, harm investment, and undermine Canada’s vision to be an energy superpower. This policy will also reduce the oil and gas sector’s capacity to invest in technologies that drive additional emission reductions, such as solvents and carbon capture, especially in our current lower price environment. As such it is more likely to undermine climate action than support it.

The federal and provincial governments have come together to advance a vision for Canadian energy in the past. In this moment, they have the opportunity once again to find real solutions to the climate challenge while harnessing the energy sector to advance Canada’s economic well-being, productivity, and global energy security.

About the author

Heather Exner-Pirot is Director of Energy, Natural Resources, and Environment at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.

Immigration

Mass immigration can cause enormous shifts in local culture, national identity, and community cohesion

By Geoff Russ for Inside Policy

It matters where immigrants come from, why they choose Canada, and how many are arriving from any single country. When it comes to countries of origin, immigration streams into Canada have become wildly unbalanced over the last decade.

Few topics have animated Canadians more than immigration in the past year.

There is broad consensus among the public that the annual intake of newcomers must fall, and polling shows both native-born and immigrant citizens agree on this. In Ottawa, the Conservative opposition has called for lower numbers, and the Liberal government ostensibly concurs.

While much of the discussion surrounding immigration has focused on economic factors like affordability and the shrinking housing supply, less attention has been paid to the cultural and political changes of welcoming more than 5 million people into the country since 2014.

Specifically, attention must be paid to the possible outcomes of importing hundreds of thousands of people from regions embroiled by war or prone to conflict. This is a necessity as digital technology proliferates and guarantees the world will be interconnected, but not united.

Mass immigration brings in far more than just people. It can cause enormous shifts in local culture, national identity, political allegiances, and community cohesion.

It matters where immigrants come from, why they choose Canada, and how many are arriving from any single country. When it comes to countries of origin, immigration streams into Canada have become wildly unbalanced over the last decade.

In 2023, almost 140,000 people immigrated to Canada from India, while the second-largest intake came from China, with 31,770 people.

This new trend is at odds with Canada’s historical immigration policies, which were more evenly weighted by country. In 2010, the top three national pools of immigration were the Philippines at 38,300 newcomers, India with 33,500, and China with 31,800.

Other countries that Canada has received increasing numbers of migrants from includes Syria, Pakistan, and Nigeria.

Past federal governments took consideration for details like economic needs and capacity for integration. Canadian immigration policy in 2025 should take into account modern communications and conflicts within certain regions as well.

21st century technology continues to advance and innovate at dizzying speeds, giving rise to immersive social platforms and instant messaging platforms like WhatsApp or Signal. This has brought the world closer together, but rather than promoting peace and understanding, it has amplified foreign conflicts and brought them to our own backyards.

Tens of thousands of migrants from the Levant have arrived since 2015, a region where anti-Zionism is deeply ingrained in the cultures, as well as full-blown antisemitism.

Since the outbreak of the Israel-Hamas War in 2023, the entire West has borne witness to antisemitic violence in Europe and North America, often perpetrated by ideologically motivated migrants.

Earlier this year, a Syrian migrant in Germany went on a stabbing spree with the intent of murdering Jews, while last September, Canadian police foiled the plot of a Pakistani man in Ontario who had planned to commit a mass killing of Jews in New York City.

Canada’s political culture has been profoundly affected by these same waves, with demographic changes forcing the federal government to alter its longstanding foreign policy positions. For example, the newly-minted Minister of Industry Mélanie Joly allegedly remarked last year that her shifting stance on the Israel-Hamas war was due to the “demographics” of her Montreal riding.

Montreal itself has become a hotbed of anti-Israeli and anti-semitic violence. Riots, property damage, and the storming of the McGill University campus have been carried out by radicals inspired by Hamas and their allies.

In 1968, the great Canadian thinker Marshall McLuhan co-authored War and Peace in the Global Village, which warned of the consequences of modern technologies erasing the boundaries of the world. McLuhan explicitly cautioned that technology would make the world smaller, and lead to conflict in his theorized global village.

Today, that village is one where Jewish students are routinely harassed on college campuses in Vancouver and Toronto, while synagogues are burnt to the ground in Melbourne. It does not matter whether the victims are Israeli or not. They are seen by their assailants as legitimate targets as part of an enemy tribe.

On May 21, two staffers at the Israeli embassy in Washington DC were shot dead by a man shouting pro-Palestinian slogans.

These sorts of imported feuds go beyond the Middle East. Global tensions in regions like the Indian subcontinent present another threat of foreign-inspired and funded violence, as well as undue political shifts.

India and Pakistan are locked in a long running standoff over the disputed territory of Kashmir.

Last month, several tourists were murdered in Kashmir by militants that India accused Pakistan of backing, leading to several low-level exchanges between the Indian and Pakistani militaries before a ceasefire was brokered. Tensions are far from dissipated, and the possibility of a full-scale confrontation between India and Pakistan remains high.

Considering those two rivals have massive diasporas in the West, a potential war on the subcontinent could radically change domestic politics in countries in Canada, Australia, and Britain.

In 2022, violent clashes broke out between Hindu and Muslim youths in the British city of Leicester following a cricket match between India and Pakistan. The street battles lasted for weeks, and threatened to restart later that year following an escalation in India and Pakistan’s clash over Kashmir. In London, demonstrators from the Pakistani and Indian communities came close to violence.

If a sporting rivalry can inspire hooliganism, a war will spark something far worse, and the globalization of the Israel-Gaza conflict is a glimpse into what that might look like.

There is historical precedent in Canada for how overseas conflicts affect domestic politics.

During the 19th century, hundreds of thousands of Irish—both Catholic and Protestant—emigrated to Canada before and after Confederation in 1867. They brought their religious feuds with them.

The militantly anti-Catholic Orange Order, run by Protestants, became one of the most powerful political forces in Ontario. They held a virtual monopoly on municipal politics in Toronto, excluded Catholics from jobs in the public service, and took part in brawls with the city’s Irish Catholic community for more than 100 years.

Thomas D’Arcy McGee, one of the Fathers of Confederation and an Irish Catholic migrant, was murdered for speaking out against the republican Fenian Brotherhood, which had infiltrated politics both in Canada and the United States.

Integration throughout successive generations mitigates and even practically eliminates the impact of imported conflicts. This was the case with the Irish sectarian divide, though it took over a century to fade away.

Worth noting is that roughly 300,000 Ukrainian refugees currently reside in Canada, having been admitted under a special visa program following the Russian invasion in 2022. It is intended to be temporary, with the expectation of repatriation once a stable peace returns to Ukraine.

Similarly to Irish-Canadians, the vast majority of the established Ukrainian-Canadian community has its roots in pre-modern Canada, and is largely well-integrated into the country’s social fabric. To date, there has been no major violence or anti-social harms inflicted upon their Russian-Canadian counterparts despite the war, or vice-versa.

Furthermore, the Canadian government has a longstanding close relationship with Kyiv, and there is far more trust and transparency regarding intent and collaboration. This is not the case with governments like China and India, the former of whom actively interferes in our elections, and the latter of which has been accused of assassinating dissidents on Canadian soil.

The existence of the iPhone, the internet, and opportunistic foreign governments makes it incredibly dangerous to not change course. That is not to imply that the average migrant is an active foreign agent. But the sheer quantity makes vetting them all a challenge.

Mitigating these threats requires strategic planning when crafting immigration policy.

Other parts of the world like Southeast Asia, Southern Europe, and Latin America are relatively stable and peaceful and are potential sources of newcomers with far lower risk of foreign interference and diasporic violence.

At-play is the stability, unity, and integrity of our political system. Canadian politics must remain fully Canadian in its focus and priorities. That cannot happen if we sleepwalk into becoming a battleground for the rest of the world.

Geoff Russ is a writer and policy analyst, and a contributor for the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.

-

armed forces1 day ago

armed forces1 day agoCanada’s Military Can’t Be Fixed With Cash Alone

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoCOVID mandates protester in Canada released on bail after over 2 years in jail

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoTrump transportation secretary tells governors to remove ‘rainbow crosswalks’

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCanada’s loyalty to globalism is bleeding our economy dry

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoAlberta Next: Alberta Pension Plan

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCarney’s spending makes Trudeau look like a cheapskate

-

Crime2 days ago

Crime2 days agoProject Sleeping Giant: Inside the Chinese Mercantile Machine Linking Beijing’s Underground Banks and the Sinaloa Cartel

-

C2C Journal23 hours ago

C2C Journal23 hours agoCanada Desperately Needs a Baby Bump