Health

The Hidden Risk of an Abortion

A disturbing study was published last month in the Journal of Psychiatric Research, which found that women who had abortions were twice as likely to be hospitalized for psychiatric disorders, substance use, and suicide attempts compared to women who were pregnant and who did not get an abortion (this category includes both pregnancies carried to term and stillbirths). The researchers had data that stretched out 17 years, so they were able to document that this risk is not just short-term, but lasts for years after the induced abortion. The first five years are when women are at the highest risk.

Highlights from the Study

- Mental health hospitalization rates are higher after abortion than live births.

- Risk is elevated for psychiatric disorders, substance use, and suicide attempts.

- Patients with preexisting mental illness or age <25 years are most at risk.

- The risk of mental disorders is most significant within five years of abortion.

- Risk of most mental disorders disappears 17 years after an abortion.

Abstract

Background

The relationship between induced abortion and long-term mental health is not clear. We assessed whether having an induced abortion was associated with an increase in the long-term risk of mental health hospitalization.

Methods

We carried out a retrospective cohort study of 28,721 induced abortions and 1,228,807 births in hospitals of Quebec, Canada, between 2006 and 2022. The exposure was induced abortion compared with other pregnancies, and the outcome was hospitalization for a psychiatric disorder, substance use disorder, or suicide attempt over time. We followed patients up to 17 years after the end of pregnancy to identify mental health-related hospitalizations. We calculated hazard ratios (HR) and 95 % confidence intervals (CI) for the association between induced abortion and mental health hospitalization, adjusted for pregnancy characteristics.

Results

Rates of mental health-related hospitalization were higher following induced abortions than other pregnancies (104.0 vs. 42.0 per 10,000 person-years). Abortion was associated with hospitalization for psychiatric disorders (HR 1.81, 95 % CI 1.72–1.90), substance use disorders (HR 2.57, 95 % CI 2.41–2.75), and suicide attempts (HR 2.16, 95 % CI 1.91–2.43) compared with other pregnancies. The associations were greater for patients who had preexisting mental illness or were aged less than 25 years at the time of the abortion. Abortion was strongly associated with mental health hospitalization within five years but risks waned over time.

Conclusion

Induced abortion is associated with an increased risk of mental health-related hospitalization in the long term but the association weakens with time.

Figures from the Article

Discussion

In this population-based study of more than 1.2 million pregnancies, having an induced abortion was associated with an increased risk of hospitalization for a mental disorder more than a decade later. Compared with live births and stillbirths, patients with induced abortions had a greater risk of admission for psychiatric disorders, substance use disorders, and suicide attempts over time. Patients with abortions who were under age 25 years or had a preexisting mental health disorder were most at risk of mental health hospitalization. The association with mental health hospitalization was greatest within five years of abortion and weakened thereafter. After 17 years of follow-up, the risk of mental health hospitalization began to resemble pregnancies that carried to term.

Addictions

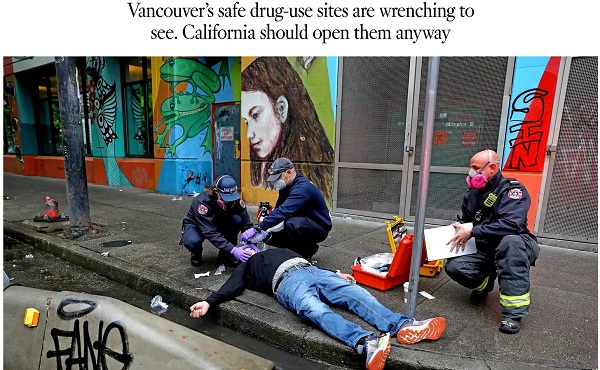

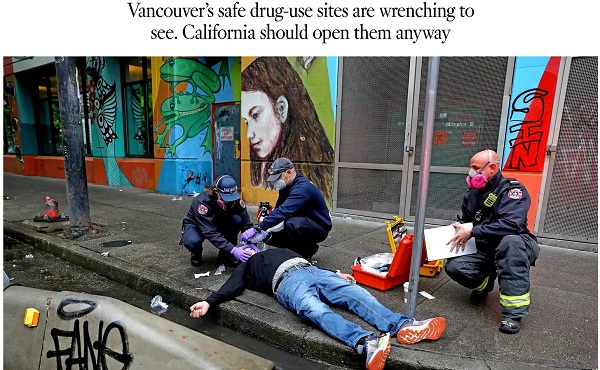

Why North America’s Drug Decriminalization Experiments Failed

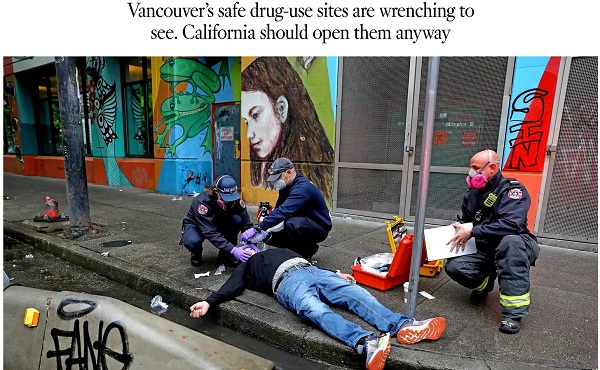

A 2022 Los Angeles Times piece advocates following Vancouver’s model of drug liberalization and treatment. Adam Zivo argues British Columbia’s model has been proven a failure.

By Adam Zivo

Oregon and British Columbia neglected to coerce addicts into treatment.

Ever since Portugal enacted drug decriminalization in 2001, reformers have argued that North America should follow suit. The Portuguese saw precipitous declines in overdoses and blood-borne infections, they argued, so why not adopt their approach?

But when Oregon and British Columbia decriminalized drugs in the early 2020s, the results were so catastrophic that both jurisdictions quickly reversed course. Why? The reason is simple: American and Canadian policymakers failed to grasp what led to the Portuguese model’s initial success.

Contrary to popular belief, Portugal does not allow consequence-free drug use. While the country treats the possession of illicit drugs for personal use as an administrative offense, it nonetheless summons apprehended drug users to “dissuasion” commissions composed of doctors, social workers, and lawyers. These commissions assess a drug user’s health, consumption habits, and socioeconomic circumstances before using arbitrator-like powers to impose appropriate sanctions.

These sanctions depend on the nature of the offense. In less severe cases, users receive warnings, small fines, or compulsory drug education. Severe or repeat offenders, however, can be banned from visiting certain places or people, or even have their property confiscated. Offenders who fail to comply are subject to wage garnishment.

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Throughout the process, users are strongly encouraged to seek voluntary drug treatment, with most penalties waived if they accept. In the first few years after decriminalization, Portugal made significant investments into its national addiction and mental-health infrastructure (e.g., methadone clinics) to ensure that it had sufficient capacity to absorb these patients.

This form of decriminalization is far less radical than its North American proponents assume. In effect, Portugal created an alternative justice system that coercively diverts addicts into rehab instead of jail. That users are not criminally charged does not mean they are not held accountable. Further, the country still criminalizes the public consumption and trafficking of illicit drugs.

At first, Portugal’s decriminalization experiment was a clear success. During the 2000s, drug-related HIV infections halved, non-criminal drug seizures surged 500 percent, and the number of addicts in treatment rose by two-thirds. While the data are conflicting on whether overall drug use increased or decreased, it is widely accepted that decriminalization did not, at first, lead to a tidal wave of new addiction cases.

Then things changed. The 2008 global financial crisis destabilized the Portuguese economy and prompted austerity measures that slashed public drug-treatment capacity. Wait times for state-funded rehab ballooned, sometimes reaching a year. Police stopped citing addicts for possession, or even public consumption, believing that the country’s dissuasion commissions had grown dysfunctional. Worse, to cut costs, the government outsourced many of its addiction services to ideological nonprofits that prioritized “harm reduction” services (e.g., distributing clean crack pipes, operating “safe consumption” sites) over nudging users into rehab. These factors gradually transformed the Portuguese system from one focused on recovery to one that enables and normalizes addiction.

This shift accelerated after the Covid-19 pandemic. As crime and public disorder rose, more discarded drug paraphernalia littered the streets. The national overdose rate reached a 12-year high in 2023, and that year, the police chief of the country’s second-largest city told the Washington Post that, anecdotally, the drug problem seemed comparable to what it was before decriminalization. Amid the chaos, some community leaders demanded reform, sparking a debate that continues today.

In North America, however, progressive policymakers seem entirely unaware of these developments and the role that treatment and coercion played in Portugal’s initial success.

In late 2020, Oregon embarked on its own drug decriminalization experiment, known as Measure 110. Though proponents cited Portugal’s success, unlike the European nation, Oregon failed to establish any substantive coercive mechanisms to divert addicts into treatment. The state merely gave drug users a choice between paying a $100 ticket or calling a health hotline. Because the state imposed no penalty for failing to follow through with either option, drug possession effectively became a consequence-free behavior. Police data from 2022, for example, found that 81 percent of ticketed individuals simply ignored their fines.

Additionally, the state failed to invest in treatment capacity and actually defunded existing drug-use-prevention programs to finance Measure 110’s unused support systems, such as the health hotline.

The results were disastrous. Overdose deaths spiked almost 50 percent between 2021 and 2023. Crime and public drug use became so rampant in Portland that state leaders declared a 90-day fentanyl emergency in early 2024. Facing withering public backlash, Oregon ended its decriminalization experiment in the spring of 2024 after almost four years of failure.

The same story played out in British Columbia, which launched a three-year decriminalization pilot project in January 2023. British Columbia, like Oregon, declined to establish dissuasion commissions. Instead, because Canadian policymakers assumed that “destigmatizing” treatment would lead more addicts to pursue it, their new system employed no coercive tools. Drug users caught with fewer than 2.5 grams of illicit substances were simply given a card with local health and social service contacts.

This approach, too, proved calamitous. Open drug use and public disorder exploded throughout the province. Parents complained about the proliferation of discarded syringes on their children’s playgrounds. The public was further scandalized by the discovery that addicts were permitted to smoke fentanyl and meth openly in hospitals, including in shared patient rooms. A 2025 study published in JAMA Health Forum, which compared British Columbia with several other Canadian provinces, found that the decriminalization pilot was associated with a spike in opioid hospitalizations.

The province’s progressive government mostly recriminalized drugs in early 2024, cutting the pilot short by two years. Their motivations were seemingly political, with polling data showing burgeoning support for their conservative rivals.

The lessons here are straightforward. Portugal’s decriminalization worked initially because it did not remove consequences for drug users. It imposed a robust system of non-criminal sanctions to control addicts’ behavior and coerce them into well-funded, highly accessible treatment facilities.

Done right, decriminalization should result in the normalization of rehabilitation—not of drug use. Portugal discovered this 20 years ago and then slowly lost the plot. North American policymakers, on the other hand, never understood the story to begin with.

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Invite your friends and earn rewards

Fraser Institute

One doctor’s battle to put patients ahead of politics

From the Fraser Institute

For decades, Canadians have been told that our health-care system is the envy of the world, a symbol of national pride. But the reality, as exposed in the new book My Fight for Canadian Healthcare by Dr. Brian Day, is far less flattering—and far more troubling. Dr. Day’s account of his 30-year battle to put patients first reveals a system bogged down by ideology, political inertia and an aversion to necessary reform. His message is clear: it’s time for Canadians to take off the rose-coloured glasses and demand a system that actually works for patients.

The book is not an argument for dismantling universal health care—it’s a plea for modernization and responsiveness. Dr. Day, an orthopedic surgeon and founder of the Cambie Surgery Centre in Vancouver, offers a front-line perspective on how rationing, administrative inefficiency and outdated policies systematically deny timely care to patients. Through detailed stories and compelling data, he documents the tragic human cost of excessive waiting lists—patients suffering needless pain, enduring irreversible deterioration, and in some cases, dying of preventable deaths.

One of the most disturbing revelations in the book is the deliberate limitation of health-care capacity by provincial governments. Faced with budget constraints, administrators limit operating room time and restrict physician access, effectively forcing patients to suffer on long waiting lists. This isn’t the result of unavoidable resource shortages; it’s a consequence of deliberate policy choices aimed at controlling spending, even if that means denying patients the care they need when they need it.

What makes this all the more unacceptable is that many of the very politicians and bureaucrats who defend this system seek care in private clinics (including Dr. Day’s Cambie Surgery Centre) when their own health is on the line. This double standard—one system for the public, another for the elite—undermines the entire moral justification of Canada’s approach to health care. If the system were truly world-class, those in power would not seek alternatives.

Dr. Day’s legal battle began in 2009 when his clinic became the target of a government lawsuit for allegedly violating an existing prohibition on patients paying with their own money for medically necessary care. This same prohibition had already been found unconstitutional in Quebec by the Supreme Court’s Chaoulli ruling in 2005, on the grounds that it violated fundamental rights to life and security.

The case dragged on for more than a decade, exposing the dysfunction of both the health-care system and the legal process meant to evaluate its constitutionality. Evidence presented in court—including government data showing thousands of patients dying while waiting for care—was damning. Unfortunately for Canadians, the British Columbia Supreme Court ultimately upheld the government’s authority to ration care and forbid patients from seeking private alternatives.

This legal defeat underscores a core truth that Dr. Day has long emphasized—Canadian health care is driven more by ideology than by evidence. The obsession with preserving a government monopoly has become an end in itself, eclipsing the system’s primary purpose: ensuring timely quality care for all. In no other sphere of life would we tolerate this. Imagine being told you couldn’t pay for private tutoring if your child’s public school was failing him. Yet this is precisely what Canadian health-care policy imposes.

Crucially, Dr. Day’s critique is rooted not in theory but in practise. He has seen firsthand the harm caused by delays, the deterioration of patients left waiting months or years for treatment, and the exodus of talented young doctors who leave Canada because the system restricts their ability of practise to their full potential. He has also seen the benefits of mixed public-private models in countries such as Australia, Sweden and Germany—countries with universal care that still allow room for private-sector innovation and competition.

Predictably, critics paint Dr. Day as a champion of privatization at any cost, but this is a gross mischaracterization. His vision is not American-style health care but rather a modernized patient-centred system that retains universal coverage while embracing flexibility, innovation and patient choice. In short, he wants Canada to catch up with the rest of the developed world, where public and private systems work together to ensure patients receive timely care regardless of their financial means.

Perhaps the most sobering aspect of My Fight for Canadian Healthcare is the reminder that reform is not only necessary, but inevitable. Canada’s population is aging, demand for care is rising, and the costs of maintaining the current system are unsustainable. Clinging to outdated structures will only deepen the crisis. The choice is not between public and private care—it’s between a system that works and one that fails.

As Dr. Day argues, the ultimate victims of our broken system are the patients themselves—ordinary Canadians left to suffer while politicians cling to outdated dogma. His fight has been long and costly, but it offers a valuable lesson: health-care reform is not about ideology. It’s about compassion, common sense and the courage to admit when something isn’t working. The time for that honesty is now.

-

Business21 hours ago

Business21 hours ago“SCAM OF THE CENTURY”: Trump vows to replace unreliable renewables with real energy

-

Media1 day ago

Media1 day agoCBC and others refuse to stop committing unmarked crimes against journalism

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day ago33 per cent jump in one year! Nearly 147,000 federal bureaucrats take six-figure salary

-

Business15 hours ago

Business15 hours agoDisney scrambles as young men reject DEI-filled franchises

-

Dan McTeague1 day ago

Dan McTeague1 day ago’Net-Zero’ Carney’s going to build new pipelines? I’ll believe it when I see it!

-

Business22 hours ago

Business22 hours agoIs Canada’s $100B+ Climate Plan Based on Shaky Science?

-

Fraser Institute2 days ago

Fraser Institute2 days agoB.C. Indigenous land claims decision leaves British Columbians in limbo

-

Addictions4 hours ago

Addictions4 hours agoWhy North America’s Drug Decriminalization Experiments Failed