Frontier Centre for Public Policy

The Church Thrives When Its Values Clash With Cultural Norms

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

By Gerry Bowler

History shows the Church is strongest when it stands apart from the mainstream

“I used to be with ‘it’, but then they changed what ‘it’ was. Now what I’m with isn’t ‘it’, and what’s ‘it’ seems weird and scary to me. It’ll happen to you!”

That moment of cartoon wisdom from Grandpa Simpson in a classic episode of The Simpsons captures a truth that every generation eventually faces. And right now, it’s the Church that finds itself out of step with what society calls “it.” But history suggests that’s exactly when the Church does its best work.

A recent example makes the point. American Christian singer and activist Sean Feucht was banned from performing in several Canadian venues by authorities who considered his views on social issues a threat to “community values.” When the Ministerios Restauracion Church in Montreal allowed one of Feucht’s presentations to proceed, protestors disrupted the event by throwing a smoke bomb into the Church. Police fined the Church $2,500.

One of Feucht’s supporters expressed shock that church values were no longer considered community values. She hasn’t been paying attention. This disconnect didn’t happen overnight—it reflects a profound cultural shift over decades.

For centuries, church values—traditional Christian teachings on life, family and morality—were understood to be the moral foundation of Canadian life. From the Catholic roots of New France to the ministers of the gospel like Tommy Douglas, a Baptist preacher and father of Canadian medicare, and Ernest Manning, an evangelical leader and longtime Alberta premier, Christian influence helped shape this country’s civic culture. Even our national anthem appeals to God.

But since the 1960s, the culture began to drift away from long-established teachings on sex, alcohol, gambling, drug use, abortion, euthanasia and marriage. In response, the largest Protestant denominations—United, Anglican and Presbyterian—watered down their doctrines and embraced the new permissive values of the day.

The results were predictable. Churches that held firm to historic teachings retained and even grew their membership. Those that compromised with secularism lost adherents and saw their influence decline. After all, why would anyone dress up for Sunday service to hear the same moral platitudes already available on every CBC morning show?

Being out of step with the culture isn’t a new role for the Church. History shows that its moral leadership often sparked real social change, especially when it stood against powerful interests.

In ancient Rome, Christians condemned the practice of leaving unwanted infants to die. When Christianity took hold among the ruling class, Roman emperors banned infanticide.

While gladiator games filled arenas with bloodlust, the Church demanded their end. When medieval knights pillaged and murdered at will, the Church established the Peace of God and the Truce of God, protecting peasants and limiting warfare to preserve crops and communities.

During the height of the African slave trade, Quakers, Anglicans and English evangelicals led the decades-long campaign to end the practice. In the 19th century, Church-led reformers fought to abolish child labour, curb alcohol abuse and win women the vote.

Today, many of the moral issues once opposed by the Church are now promoted or normalized by the state itself. In 21st-century Canada, the government sells drugs, alcohol and lottery tickets. Pornography is widely accessible online. Euthanasia is now considered a form of health care in Canada, including in cases involving mental illness and the elderly.

That Church values no longer align with community values should come as no surprise.

Nor should it be cause for alarm. The Church is once again where it has often been: outside the halls of power, surrounded by cultural opposition. And that is where it has always done its most important work.

Gerry Bowler is a Canadian historian and a senior fellow of the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

Education

Classroom Size Isn’t The Real Issue

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

The real challenge is managing classrooms with wide-ranging student needs, from special education to language barriers

Teachers’ unions have long pushed for smaller class sizes, but the real challenge in schools isn’t how many students are in the room—it’s how complex those classrooms have become. A class with a high proportion of special needs students, a wide range of academic levels or several students learning English as a second language can be far more difficult to teach than a larger class where students are functioning at a similar level.

Earlier this year, for example, the Elementary Teachers’ Federation of Ontario announced that smaller class sizes would be its top bargaining priority in this fall’s negotiations.

It’s not hard to see why unions want smaller classes. Teaching fewer students is generally easier than teaching more students, which reduces the workload of teachers. In addition, smaller classes require hiring more teachers, and this amounts to a significant financial gain for teachers’ unions. Each teacher pays union dues as part of membership.

However, there are good reasons to question the emphasis on class size. To begin with, reducing class size is prohibitively expensive. Teacher salaries make up the largest percentage of education spending, and hiring more teachers will significantly increase the amount of money spent on salaries.

Now, this money could be well spent if it led to a dramatic increase in student learning. But it likely wouldn’t. That’s because while research shows that smaller class sizes have a moderately beneficial impact on the academic performance of early years students, there is little evidence of a similar benefit for older students. Plus, to get a significant academic benefit, class sizes need to be reduced to 17 students or fewer, and this is simply not financially feasible.

In addition, reducing class sizes means spending more money on teacher compensation (including salaries, pensions and benefits). Also, it leads to a decline in average teacher experience and qualifications, particularly during teacher shortages.

As a case in point, when the state of California implemented a K-3 class-size reduction program in 1996, inexperienced or uncertified teachers were hired to fill many of the new teaching positions. In the end, California spent a large amount of money for little measurable improvement in academic performance. Ontario, or any other province, would risk repeating California’s costly experience.

Besides, anyone with a reasonable amount of teaching experience knows that classroom complexity is a much more important issue than class size. Smaller classes with a high percentage of special needs students are considerably more difficult to teach than larger classes where students all function at a similar academic level.

The good news is that some teachers’ unions have shifted their focus from class size to classroom complexity. For example, during the recent labour dispute between the Saskatchewan Teachers’ Federation (STF) and the Saskatchewan government, the STF demanded that a classroom complexity article be included in the provincial collective agreement. After the dispute went to binding arbitration, the arbitrator agreed with the STF’s request.

Consequently, Saskatchewan’s new collective agreement states, among other things, that schools with 150 or more students will receive an additional full-time teacher who can provide extra support to students with complex needs. This means that an extra 500 teachers will be hired across Saskatchewan.

While this is obviously a significant expenditure, it is considerably more affordable than arbitrarily reducing class sizes across the province. By making classroom complexity its primary focus, the STF has taken an important first step because the issue of classroom complexity isn’t going away.

Obviously, Saskatchewan’s new collective agreement is far from a panacea, because there is no guarantee that principals will make the most efficient use of these additional teachers.

Nevertheless, there are potential benefits that could come from this new collective agreement. By getting classroom complexity into the collective agreement, the STF has ensured that this issue will be on the table for the next round of bargaining. This could lead to policy changes that go beyond hiring a few additional teachers.

Specifically, it might be time to re-examine the wholesale adoption of placing most students, including those with special needs, in regular classrooms, since this policy is largely driving the increase in diverse student needs. While every child has the right to an education, there’s no need for this education to look the same for everyone. Although most students benefit from being part of regular academic classes, some students would learn better in a different setting that considers their individual needs.

Teachers across Canada should be grateful that the STF has taken a step in the right direction by moving beyond the simplistic demand for smaller class sizes by focusing instead on the more important issue of diverse student needs.

Michael Zwaagstra is a senior fellow with the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

Frontier Centre for Public Policy

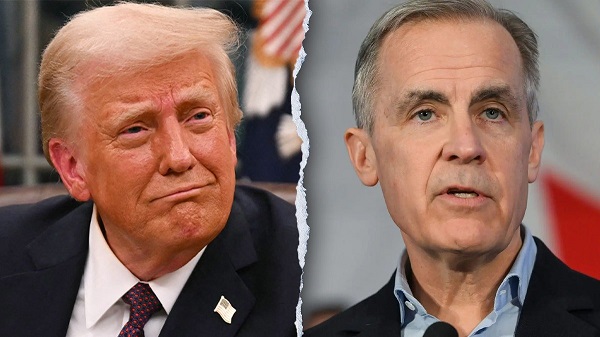

Canada’s Democracy Is Running On Fumes

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

By Gerry Bowler

Prime ministerial control, weak Parliament and a dependent press have left voters with little more than a ritual trip to the ballot box

Canadians take comfort in U.S. dysfunction, but the foundations of our own democracy are already showing serious strain

Canada isn’t the strong democracy we like to believe. Behind the peaceful elections and parliamentary rituals lies a system where power is concentrated in the hands of one person: the prime minister.

Since Confederation, Canada has avoided coups and revolutions. Governments have changed hands through orderly elections, a record many countries envy. On the surface, it looks like a stable democracy.

But look closer, and the cracks show.

The 1982 Constitution enshrined a Charter of Rights and Freedoms promising equality for all, and then immediately allowed governments to override those rights with the “notwithstanding clause,” which lets legislatures pass laws even if they conflict with the Charter.

The Emergencies Act, used for the first time during the 2022 trucker protests, gives Ottawa extraordinary powers to suspend freedoms and compel action. Its use included freezing bank accounts without court orders and compelling tow truck operators to provide their services to remove the vehicles, measures that left many Canadians unsettled about how quickly their rights can be curbed.

Parliamentary practice has also made the prime minister one of the most powerful elected leaders in the world. He decides who can run under his party’s banner, when MPs may speak and who sits in cabinet. He appoints the heads of federal agencies, judges, ambassadors and senators. In theory, these powers rest with the Crown. In practice, it is the prime minister who even chooses the governor general. Unlike Britain, where leaders must contend with internal party democracy, Canadian prime ministers enforce tight discipline, leaving backbench MPs with little influence.

This isn’t just theory. Pierre Trudeau’s iron grip on his caucus, Stephen Harper’s strict message control and Justin Trudeau’s demands for near-total loyalty all show how party discipline can stifle independent voices in Parliament.

When opposition parties pose a threat, a prime minister can simply prorogue Parliament, temporarily shutting it down without dissolving it, and avoiding debate. Jean Chrétien, Harper and Trudeau have all used this tactic when pressure mounted. After an election, the first sitting can be delayed for nearly a year. Even when Parliament does sit, question period, once meant to hold governments accountable, has become little more than a trading of insults. Canadians who tune in often come away with the impression of theatre, not oversight.

Parliament’s supremacy has been further eroded by section 52(1) of the Constitution, which gives the Supreme Court power to strike down laws passed by elected representatives and create new rights and obligations in their place. Courts have struck down laws on abortion, safe-injection sites and mandatory minimum sentences, reshaping policy without a vote in the House of Commons.

Meanwhile, the press, long considered democracy’s watchdog, now relies heavily on government subsidies such as the federal media bailout program. Sold as a lifeline to preserve journalism, it has raised unavoidable questions about independence. Critics argue that when newsrooms depend on Ottawa for survival, it blunts their willingness to challenge the same government that funds them. In a country where a strong, adversarial press is essential, the appearance of influence is almost as damaging as direct control.

All of this has reduced Canadian democracy to little more than a ritual trip to the ballot box every four or five years. With power so centralized, many voters understandably wonder whether their participation matters. No surprise, then, that a third of Canadians don’t bother to vote, with even lower turnout in provincial and municipal elections.

Canadians often look south at the polarization and chaos in American politics and congratulate ourselves for avoiding the same fate. But that smugness is dangerous. The U.S. reminds us how quickly democratic institutions can fray when power is abused and trust collapses. Canada is not immune.

The warning signs are here. Keep ignoring them, and our democracy will collapse: not with a bang but with a whimper.

Gerry Bowler is a Canadian historian and a senior fellow of the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoThe Grocery Greed Myth

-

Frontier Centre for Public Policy7 hours ago

Frontier Centre for Public Policy7 hours agoCanada’s Democracy Is Running On Fumes

-

COVID-192 days ago

COVID-192 days agoTamara Lich says she has no ‘remorse,’ no reason to apologize for leading Freedom Convoy

-

Crime2 days ago

Crime2 days agoCanada’s safety minister says he has not met with any members of damaged or destroyed churches

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoTrump Warns Beijing Of ‘Countermeasures’ As China Tightens Grip On Critical Resources

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoTrump gets an honourable mention: Nobel winner dedicates peace prize to Trump

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoTax filing announcement shows consultation was a sham

-

Education7 hours ago

Education7 hours agoClassroom Size Isn’t The Real Issue