National

Taxpayers Federation presents Teddy Waste Awards for worst government waste

From the Canadian Taxpayers Federation

Author: Franco Terrazzano

The Canadian Taxpayers Federation presented its 26th annual Teddy Waste Awards to CBC President Catherine Tait for handing out millions in bonuses while announcing hundreds of layoffs; the Mission Cultural fund for its sex-themed artistic performances; and the city of Regina for its Experience Regina rebrand fiasco.

“Because it spent buckets of taxpayer cash funding birthday parties and photo exhibits for celebrities, and making things awkward for countries around the world with sex-themed artistic performances, the Mission Cultural Fund earned the Lifetime Achievement award for waste,” said Franco Terrazzano, CTF Federal Director.

“Tait is winning a Teddy Award because she handed out millions in bonuses despite announcing hundreds of layoffs just before Christmas, only to turn around and beg for more taxpayer cash.

“The Alberta Foundation for the Arts spent tens of thousands flying an artist to New York, Estonia and South Korea so she could flop around on a futon for a couple minutes and showcase a painting that can best be described as ants on a pop tart.

“The city of Regina came up with snappy slogans like, ‘Show us your Regina,’ and ‘Regina: the city that rhymes with fun.’ After spending $30,000 and facing backlash, the city ditched the entire rebrand so it won a Teddy Waste Award.”

The Teddy, a pig-shaped trophy the CTF annually awards to governments’ worst waste offenders, is named after Ted Weatherill, a former federal appointee who was fired in 1999 for submitting a raft of dubious expense claims, including a $700 lunch for two.

This year’s winners include:

- Municipal Teddy winner: The city of Regina

Regina spent $30,000 rebranding Tourism Regina to Experience Regina. But after facing backlash, the city scrapped the rebrand. And Regina taxpayers are out $30,000.

- Provincial Teddy winner: Alberta Foundation for the Arts

The Alberta Foundation for the Arts spent $30,000 flying an artist around the world to produce art few taxpayers would ever willingly buy or pay to see.

- Federal Teddy winner: CBC President Catherine Tait

Tait handed out $15 million in bonuses to CBC brass in 2023 as she announced hundreds of layoffs weeks before Christmas and lobbied the government for more money. Bonuses at the CBC total $114 million since 2015.

- Lifetime Teddy winner: The Mission Cultural Fund

The Mission Cultural Fund spent $10,000 on a birthday party for Margaret Atwood in New York, $52,000 for a photo exhibit for rockstar Bryan Adams, $8,800 on a sex toy show in Germany and $12,000 for senior citizens to talk about their sex lives in front of live audiences.

You can find the backgrounder on this year’s Teddy Waste Award nominees and winners HERE.

Todayville is a digital media and technology company. We profile unique stories and events in our community. Register and promote your community event for free.

The Vials and the Damage Done: Canada’s National Microbiology Laboratory Scandal, Part II

Top Fauci Aide Allegedly Learned To Make ‘Smoking Gun’ Emails ‘Disappear,’ Testimony Reveals

Prime minister’s misleading capital gains video misses the point

COVID-19

The Vials and the Damage Done: Canada’s National Microbiology Laboratory Scandal, Part II

Published on May 19, 2024

From the C2C Journal

By Peter Shawn Taylor

In China, minor security infractions are routinely punished with lengthy jail terms in dreadful conditions. In Canada, it’s just the opposite. Clear evidence of espionage is rewarded with a free pass back home after the mission is complete. Neglecting our national security in this way may suit the Justin Trudeau government, but it is doing great harm to Canada’s relationship with its most important allies. In the concluding instalment of his two-part series, Peter Shawn Taylor examines the many ways in which the spy scandal at the National Microbiology Laboratory in Winnipeg has damaged Canada’s international standing and contributed to the growing perception that Canada is a foreign agent’s happy place. (Part I is here.)

It is said there are two kinds of secrets in Ottawa: secrets of national importance and secrets of political importance. Some things can’t be publicly revealed because it might endanger Canada’s national security, imperil diplomatic negotiations or weaken our international competitive position. And some other things are kept away from the public eye simply because the information could prove damaging to the government of the day. One of the many questions arising from the recent release of a massive collection of declassified documents related to the spy scandal at Canada’s top-security National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) in Winnipeg is in which category this once-secret trove of information belongs.

As described in Part I of this series, the Justin Trudeau government fought ferociously to prevent the release of the files regarding married NML scientists Xiangguo Qiu and Keding Cheng and their connection to Chinese military interests. At one point, the government even threatened to sue the Speaker of the House of Commons to keep the material secret. Following the 2021 election, however, the weakened minority Liberal government relented and made the documents available to a special ad hoc committee of MPs and judges, who then decided it was in the public’s interest for most of the information to be declassified.

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s (top left) government fought hard to avoid disclosing classified documents concerning scientist couple Xiangguo Qiu and Keding Cheng (bottom left, left to right) – suspected of using their positions at Winnipeg’s top-security National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) (bottom right) to further the interests of Communist China. (Sources of photos: (top left) CBC; (bottom left) Governor General’s Innovation Awards; (bottom right) Winnipeg Architecture Foundation)

Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s (top left) government fought hard to avoid disclosing classified documents concerning scientist couple Xiangguo Qiu and Keding Cheng (bottom left, left to right) – suspected of using their positions at Winnipeg’s top-security National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) (bottom right) to further the interests of Communist China. (Sources of photos: (top left) CBC; (bottom left) Governor General’s Innovation Awards; (bottom right) Winnipeg Architecture Foundation)

The 623-page document, released this past February, includes reports from the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) and other internal briefings that reveal the many ways Qiu and Cheng acted against the interests of Canada. This includes clandestinely as well as openly transferring intellectual and physical property to Chinese institutions in addition to allowing access to their lab by Chinese researchers, many of whom had direct links to China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) and its bioweapons aspirations. Qiu and Cheng also appear to have been involved with numerous Chinese “talent” programs – thinly-veiled espionage schemes designed to steal know-how from other countries.

Qiu appears to have played a leading role in several significant research projects at the now-notorious Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) while also working for Canada’s federal government. Of note, she arranged to send 30 vials of deadly Ebola and Henipah virus samples from NML’s stockpile to the WIV for reasons that were deliberately kept hidden from her Canadian employers. After their deceptions were uncovered and they were fired from the NML, Qiu and Cheng quietly left the country without any legal consequences. They are currently living in China under new names, evidently working in their preferred occupations.

“Deeply embarrassing”: China expert and former diplomat Charles Burton says the long delay in releasing the declassified documents, along with a flurry of other China-related bills and hearings in Ottawa, speaks to the fact “the government has become very vulnerable on China.”

“Deeply embarrassing”: China expert and former diplomat Charles Burton says the long delay in releasing the declassified documents, along with a flurry of other China-related bills and hearings in Ottawa, speaks to the fact “the government has become very vulnerable on China.”

With all this finally in the public domain, it’s now possible to determine why the Liberals were so intent on keeping the files secret. Does this information harm Canada’s national interests, or merely the political interests of the Trudeau Liberals? In fact, it does great damage to both. And much more besides.

Red-faced on China

“This is deeply embarrassing for the government,” observes Charles Burton. The long battle over keeping the NML documents secret, he says in an interview, “was mostly about covering up poor decisions made by the people in charge of the lab while two scientists carried on this extraordinary relationship with China.” Burton is a senior fellow at Sinopsis, a China-focused think-tank based in Prague; he’s also a former diplomat at Canada’s embassy in Beijing and a recently retired professor of political science at Brock University in St. Catharines, Ontario. While Qiu and Cheng’s surreptitious connections to China were initially uncovered in 2018, Burton notes it wasn’t until 2021 that they were finally fired, and it took another three years before all the details were released. “That something so egregious was kept from the public for so long is really quite troubling,” he says.

The “troubling” NML scandal is just one of many China-related issues bedeviling the federal Liberals. The documents landed just ahead of the current Public Inquiry into Foreign Interference in Federal Electoral Processes and Democratic Institutions, which also coincides with new legislation on the registry of foreign agents. This recent flurry of activity “shows the government has become very vulnerable on China,” Burton observes.

‘The Liberal Party still doesn’t get the message that China is not a nation we can engage with, without significant cost to the integrity of Canadian values,’ Burton says.

The foreign interference inquiry’s initial report, for example, establishes clear evidence of Chinese involvement in several electoral constituencies during the 2019 and 2021 federal elections. One particularly egregious example is Trudeau’s refusal to act on CSIS warnings about possible Chinese interference at a Liberal nomination meeting in the Toronto riding of Don Valley North (DVN) in 2019 because, as inquiry commissioner Marie-Josée Hogue wrote, doing so could “have direct electoral consequences as the [Liberal Party of Canada] is expected to win DVN.” In other words, Trudeau put his party’s election prospects – and his own desire to remain prime minister – ahead of concerns about China’s influence over Canada’s democratic processes.

That the Liberals are soft on China is hardly a revelation. As Burton notes, it dates back to Trudeau’s failed attempt to open free trade talks with China in 2017. Since then, his Liberal government has been reluctant to treat China as the threat to Canada it has repeatedly proved itself to be. Instead, Ottawa has gone to great lengths to avoid angering Beijing. Examples include the long delay in banning Huawei from Canada’s 5G networks, China’s years-long detention of the Two Michaels, the lingering presence of secret Chinese police stations in Canada, the David Johnson special rapporteur debacle, and on and on.

The Liberals’ soft spot: Following Trudeau’s failed attempt to obtain a free trade deal with China – shown here meeting Chinese President Xi Jinping in Beijing, December 2017 – his government has repeatedly avoided confronting China on many significant issues related to Canada’s national security. (Source of photo: The Canadian Press/Sean Kilpatrick)

The Liberals’ soft spot: Following Trudeau’s failed attempt to obtain a free trade deal with China – shown here meeting Chinese President Xi Jinping in Beijing, December 2017 – his government has repeatedly avoided confronting China on many significant issues related to Canada’s national security. (Source of photo: The Canadian Press/Sean Kilpatrick)

Asked if the recent blitz of activity on the China file represents a sea change in the current government’s attitude towards China, Burton remains deeply skeptical. “I don’t think the Liberals are prepared to do anything that would ever permanently compromise their larger project of Canada gaining significant market share in China,” he says, adding, “the Liberal Party still doesn’t get the message that China is not a nation we can engage with, without significant cost to the integrity of Canadian values.”

The Weakest Link

While clearly damning, the incremental damage done by the NML files to the Liberals’ reputation on China is likely minimal. It’s hard to imagine it getting any worse. The more significant blow, says Christian Leuprecht, is to Canada’s international reputation as a vigilant and reliable ally. “For years the Liberals have been accused of not taking the China threat seriously,” says Leuprecht, a national security expert and professor of political science at Queen’s University and the Royal Military College of Canada, both located in Kingston, Ontario. “As a result, Canada is currently under significant international scrutiny, especially from our allies in NATO and the U.S., who are concerned about the extent of Chinese infiltration of Canadian political institutions.”

In friendly Western countries, Leuprecht observes in an interview, the Trudeau government’s passivity in the face of Chinese aggression has created the perception Canada does not take matters of national security or defence seriously. And this is weakening the country’s stature abroad. Perhaps the biggest consequence is that Canada is no longer treated as a top-tier member of NATO, the premier Western military alliance. “We are increasingly being left out of meetings, our speaking time is vastly reduced and information is not being shared,” Leuprecht observes.

“Our worst fears”: According to national security expert Christian Leuprecht, the NML spy scandal is a significant blow to Canada’s international reputation; the revelation that Chinese agents penetrated Canada’s highest-security biohazard lab reinforces the belief that Canada is “the weak link” among Western allies.

“Our worst fears”: According to national security expert Christian Leuprecht, the NML spy scandal is a significant blow to Canada’s international reputation; the revelation that Chinese agents penetrated Canada’s highest-security biohazard lab reinforces the belief that Canada is “the weak link” among Western allies.

This contention is backed by Kerry Buck, Canada’s former ambassador to NATO. In a recent interview with the CBC Buck explained that Canada currently occupies NATO’s so-called “quadrant of shame” due to its poor track record on both defence spending and military research. Other evidence of Canada’s waning relevance among its allies includes its exclusion from the expanding Australia/UK/U.S. (AUKUS) defence relationshipand from the Quadrilateral Security Dialogue, an informal pact among the U.S., Australia, Japan and India meant to contain Chinese expansion in the Pacific and Indian oceans.

At a time when our allies seem less willing to engage with Canada on defence matters, evidence that our highest-security biohazard lab was exploited by federally-employed Chinese agents strikes to the very core of our reliability. “This is confirmation of our worst fears,” says Leuprecht. “No other country, at least from what we know, has experienced the same degree of infiltration. Everything in these documents reinforces the perception that Canada is the weak link.”

Leuprecht emphasizes that Canada is a small player in the intelligence world, and the worsening perception that the country can’t be trusted to keep its own secrets safe will give allied countries further pause when considering whether to share intelligence with Canada or to include it in operational plans. “None of our allies really needs Canada [in order] to do the things they want to do,” Leuprecht says. “So this significantly reduces our leverage and influence to do the things we want to do internationally. That’s what’s really at stake here.”

“Quadrant of shame”: Kerry Buck (left), Canada’s former ambassador to NATO, notes that her country belongs to a special category of underperforming NATO members due to its lack of commitment on defence spending and military research; this perception has also seen Canada excluded from newly-established security partnerships such as the Australia/UK/U.S. (AUKUS) defence relationship. Shown at right, an AUKUS meeting in March 2023. (Sources of photos: (left) The Foreign Policy Project; (right) Chad J. McNeeley, DOD)

Who Dropped the Ball?

Beyond the harm done to Canada’s political and international reputations, the release of the Qiu-Cheng files puts the performance of domestic agencies involved in the affair, including CSIS, the RCMP and Canada’s federal bureaucracy, under the microscope as well.

Alongside the many Canadian journalists and politicians who have been pouring through the documents, Leuprecht notes that foreign intelligence services will also be studying them carefully and making their own judgements. “What will German intelligence or MI6 or the CIA think about collaborating with Canada in the future when they read these files?” asks Leuprecht. “The first thing they will see is a bunch of rookie mistakes.”

PHAC’s handling of the two scientists was a tedious and unhurried affair, frequently bogged down by human resources requirements and union grievances, including allegations the original CSIS investigation was racist.

As described in Part I, Qiu and Cheng first came to the attention of CSIS following a routine “insider threat briefing” at the NML in August 2018. An initial investigation into their activities turned up plenty of worrisome evidence, including a Chinese-registered patent filed in Qiu’s name and numerous violations of NML security protocols by Cheng regarding data storage, email security and access to the lab by his foreign research students. All of this could have been sufficient to immediately remove the pair from Canada’s only Level 4 Biosafety Laboratory (BSL4). Yet they didn’t lose their security clearances until July 2019, and weren’t fired until January 2021. Should CSIS bear any responsibility for this lengthy delay?

Phil Gurski is a former strategic analyst at CSIS and principal of Borealis Threat and Risk Consulting. He’s also the author of several books on terrorism. While readily admitting a bias in favour of his former colleagues, Gurski says his reading of the documents is that CSIS acquitted itself ably throughout the affair. In quickly identifying Qiu and Cheng as possible threats, he says in an interview, “CSIS did its job properly. It found things that were inconsistent and worrisome. If someone else dropped the ball, that’s on them.”

Someone else dropped the ball: Phil Gurski, a former strategic analyst at the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS), says the agency did its job by quickly identifying Qiu and Cheng as possible security threats and informing its federal clients of this fact. Shown at left, CSIS national headquarters building in Ottawa. (Source of left photo: CSIS Canada/Facebook)

Someone else dropped the ball: Phil Gurski, a former strategic analyst at the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS), says the agency did its job by quickly identifying Qiu and Cheng as possible security threats and informing its federal clients of this fact. Shown at left, CSIS national headquarters building in Ottawa. (Source of left photo: CSIS Canada/Facebook)

Gurski points out that CSIS is merely an intelligence-gathering agency and is not allowed to arrest anyone or carry out any other law enforcement activities. It can only make recommendations to the federal institutions it serves. When it came to dealing with Qiu and Cheng, that decision rested with the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), which oversees the NML. As explained in Part I, PHAC’s handling of the two scientists was a tedious and unhurried affair, frequently bogged down by human resources requirements and union grievances, including allegations the original CSIS investigation was racist.

Leuprecht further suggests the NML was slow to react because senior administrators were blinded by the celebrity of Qiu, who won a Canadian Governor General’s Innovation Award in 2018 and was internationally recognized for her work on Ebola. “The lab had this superstar scientist and it prioritized a research culture and international collaboration over national security procedures,” he asserts.

“Superstar scientist”: According to Leuprecht, Qiu’s international reputation could have blinded the NML to the concerns that she and her husband were secretly working on behalf of China. Shown, Qiu (at right) accepts a Governor General’s Innovation Award at Rideau Hall from Governor General Julie Payette in 2018. (Source of photo: CBC)

“Superstar scientist”: According to Leuprecht, Qiu’s international reputation could have blinded the NML to the concerns that she and her husband were secretly working on behalf of China. Shown, Qiu (at right) accepts a Governor General’s Innovation Award at Rideau Hall from Governor General Julie Payette in 2018. (Source of photo: CBC)

As for CSIS’s conduct, Leuprecht agrees with Gurski’s positive assessment. “My sense is that CSIS did what it was supposed to do,” he says. “There is no suggestion they didn’t take the threat seriously.” Canada’s rookie mistakes, he explains, lie with the bureaucrats and politicians who should have acted with greater alacrity on the information they were given.

Picking Flowers, Making Honey

When he released the once-secret documents in February, federal Health Minister Mark Holland, who is responsible for PHAC, tried to explain away the massive security breach by arguing that such a thing had been impossible to predict at the time. “The extent to which China was attempting to influence the scientific community or to interfere in Canada’s domestic affairs was not known to the extent it is today,” he declared at a press conference the day the files were released. “The threat environment was in a very different place.”

Such claims of innocence are absurd, snaps Leuprecht. Chinese intentions regarding the theft of Western knowledge were obvious prior to the investigation into Qiu and Cheng. He points to a 2018 report by the Australian Strategic Policy Institute (ASPI), entitled Picking Flowers, Making Honey, that detailed many years of rampant Chinese infiltration of Western universities at the behest of PLA interests.

ASPI data showed Canada ranked third, behind the U.S. and UK, in terms of problematic collaboration between PLA scientists and institutions of higher learning. If that reference is too obscure, Leuprecht offers up his own Toronto Star commentary from the same year headlined “China’s silent invasion of Western universities” that provided a similar warning. “To claim no one knew what China was up to by 2019 is nonsense, complete nonsense,” he fumes. Besides, given the NML’s status as Canada’s highest-security biohazard lab, those in charge should have been alert for all possible risks and incursions, not just those from familiar enemies.

Today, even the Trudeau government seems to grudgingly acknowledge it took far too long to recognize the threat Qiu and Cheng posed to Canada’s national security. During a grilling by Conservative MP Michael Chong at the House of Common’s Canada-China Committee last month, Nathalie Drouin, national security intelligence advisor to the prime minister and Deputy Clerk of the Privy Council, admitted that, “From the first signal to the moment the two scientists were put on leave, yes there is a timeline that needs to be looked at.” In response Chong pointed out that the Royal Bank of Canada recently fired its Chief Financial Officer for breaching its code of conduct after an investigation that lasted less than a month. “Two and-a-half years to terminate someone for cause seems like an awfully long time,” he remarked drily.

In 2020 U.S. President Donald Trump cancelled the visas of more than 1,000 Chinese students and researchers in the U.S. because of their links to universities with ties to the Chinese military.

Despite the many obvious failures in monitoring access to and activities within Canada’s only BSL4 lab, it seems remarkable that no one other than Qiu and Cheng has ever been held to account for the many security oversights and errors in judgement. During his appearance before the Canada-China Committee on April 8, Holland maintained that “the Public Health Agency acted appropriately throughout the process” and said he did not expect anyone else to be fired as a result. He further claimed Ottawa has fixed all the holes in its security procedures revealed by the NML scandal. Then again, Holland previously asserted that “at no time did sensitive information leave the country,” a patently false statement given the wealth of know-how Qiu clandestinely shared with the WIV, not to mention the 30 vials of deadly virus samples she delivered to Wuhan.

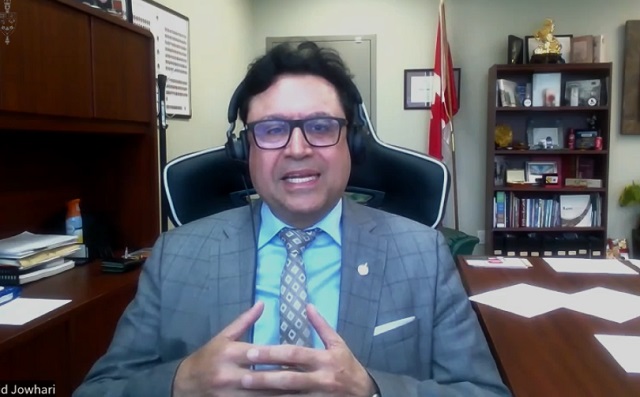

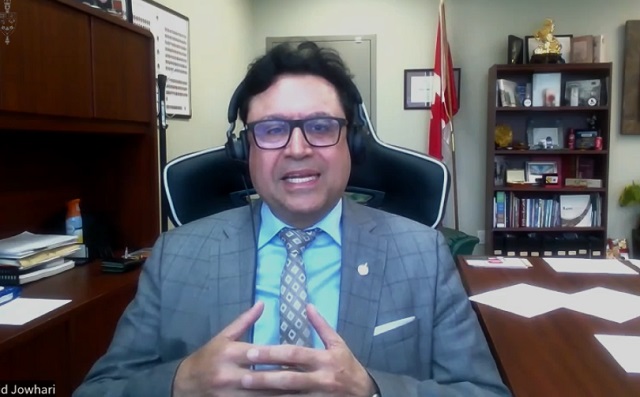

“An awfully long time”: Under questioning from Conservative MP Michael Chong (left) at an April meeting of the House of Common’s Canada-China Committee, Nathalie Drouin (right), national security intelligence advisor to the prime minister, reluctantly agreed it took far too long to fire Qiu and Cheng. (Source of screenshots: House of Commons)

“An awfully long time”: Under questioning from Conservative MP Michael Chong (left) at an April meeting of the House of Common’s Canada-China Committee, Nathalie Drouin (right), national security intelligence advisor to the prime minister, reluctantly agreed it took far too long to fire Qiu and Cheng. (Source of screenshots: House of Commons)

As for the RCMP, it claims – with an apparently straight face – to be still investigating Qiu and Cheng. This despite the fact they are now living and working in China, far from the Mounties’ reach. While they may have escaped Canadian justice, Gurski says it’s obvious to him that Qiu and Cheng broke Canadian laws. “You had two people who weren’t who they said they were and who had access to very sensitive technology and information working for a country that is not an ally of Canada,” Gurski explains. “At a minimum, I’d say that’s espionage.”

Leuprecht agrees. “That they were allowed to walk out of the country seems quite stunning,” he notes. “If you want to keep someone in the country, there are lots of ways to go about it.” As it was, they apparently left during the Covid-19 pandemic at a time when China had closed its borders to international air travel. This suggests a deliberate arrangement between Canada and China to keep the whole matter quiet. That’s not how our neighbours do it.

Tougher Action South of the Border

In 2020 U.S. President Donald Trump cancelled the visas of more than 1,000 Chinese students and researchers in the U.S. because of their links to universities with ties to the Chinese military. At the time, this presidential proclamation was widely decried as a “costly policy” motivated by “anti-Asian racism”. Today, it seems like common sense, particularly since the Biden Administration has kept it in place.

No pussy-footing around: The U.S. takes a firm approach towards potential Chinese espionage and frequently announces the prosecution of researchers and academics who have hidden their participation in China’s notorious Thousand Talents Program.

No pussy-footing around: The U.S. takes a firm approach towards potential Chinese espionage and frequently announces the prosecution of researchers and academics who have hidden their participation in China’s notorious Thousand Talents Program.

Regardless of who is in the White House, the U.S. takes a far stricter view of Chinese interference than does Canada. The FBI maintains a website solely designed to warn American employers about the threat posed by China’s numerous “talent” programs. And the U.S. Department of Justice regularly prosecutes American residents who hide their involvement in such schemes. In 2021, NASA scientist Mayya Mayyappan was fined and sentenced to a month in jail for lying about his participation in China’s national Thousand Talents Program (TTP), as well as hiding evidence of his association with a Chinese university. Last year Charles Lieber, former chair of Harvard University’s Chemistry and Chemical Biology Department, was similarly punished for his long-time secret affiliation with the TTP and for failing to pay taxes on the US$50,000 per month it was paying him.

In addition to cracking down on talent program participants, the U.S. takes a tougher stance on all forms of espionage and intellectual theft. Two months ago, for example, the FBI announced the arrest of Canadian Klaus Pflugbeil and Chinese national Yilong Shao for allegedly conspiring to steal information from a Tesla-owned battery plant in Canada on behalf of Chinese interests. “Today’s arrest demonstrates that this Office will prosecute those who engage in theft of trade secrets and places U.S. companies at a competitive disadvantage, undermines innovation and creates a potential national security risk,” reads the U.S. Department of Justice press release. You won’t find such sternly-worded press releases – or the actions to back them up – in Canada.

First try: Electric-car battery expert Yuesheng Wang, a former Hydro-Québec employee, is the only person ever charged in Canada with economic espionage under the 2001 Security of Information Act. He is still awaiting trial. (Sources of photos: (left) Yuesheng Wang/LinkedIn; (right) Gene.arboit, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0)

First try: Electric-car battery expert Yuesheng Wang, a former Hydro-Québec employee, is the only person ever charged in Canada with economic espionage under the 2001 Security of Information Act. He is still awaiting trial. (Sources of photos: (left) Yuesheng Wang/LinkedIn; (right) Gene.arboit, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0)

In fact, only one person has ever been charged in Canada with economic espionage under the federal Security of Information Act of 2001. Yuesheng Wang was an electric car battery expert at Hydro-Québec when he was arrested in 2022 for allegedly participating in a Chinese talents program and illegally transferring corporate knowledge to China. He is still awaiting trial.

The enormous discrepancy in how Canada and the U.S. deal with such matters is partly explained by flaws in Canada’s legal system regarding the investigation and prosecution of espionage. As an intelligence-gathering service, CSIS is best placed to identify such crimes. And while it can’t enforce any laws on its own, it can share its findings with the RCMP, Canada’s national police force. Unfortunately, this relationship is often awkward and complicated by the fact CSIS intel is not admissible in court because the agency refuses to disclose its sources and methods. “If defence lawyers ever get a whiff of the fact the RCMP has relied on CSIS information,” warns Gurski, “they will demand to test that information in court.” As a result, cases built on CSIS evidence can collapse during trial or are never prosecuted in the first place. It is therefore possible that Qiu and Cheng were allowed to leave the country because Crown prosecutors knew the mountain of evidence against them was inadmissible. The FBI, on the other hand, is both an intelligence gathering and law enforcement agency, and accordingly faces none of these structural problems.

In addition to a serious gap in Canadian law enforcement capabilities, Gurski points out Canada also lacks a “culture of national security”. The politicians and bureaucrats on the receiving end of CSIS reports habitually discount or ignore the evidence they contain because they put a low priority on issues of national security. This is one of the main takeaways from the current foreign interference inquiry: repeated CSIS warnings about Chinese sabotage of Liberal Party nomination meetings or intimidation directed at Conservative MPs (including Chong) were simply not acted upon because no one thought it was very important.

An awkward relationship: Prosecuting spies in Canada is complicated by the fact CSIS refuses to disclose its sources and methods in court, while the RCMP, Canada’s national police service, lacks CSIS’s expertise in intelligence gathering. Shown, CSIS Director David Vigneault (left) and RCMP Commissioner Michael Duheme (right) at a parliamentary hearing in February 2024. (Source of photo: The Canadian Press/Justin Tang)

An awkward relationship: Prosecuting spies in Canada is complicated by the fact CSIS refuses to disclose its sources and methods in court, while the RCMP, Canada’s national police service, lacks CSIS’s expertise in intelligence gathering. Shown, CSIS Director David Vigneault (left) and RCMP Commissioner Michael Duheme (right) at a parliamentary hearing in February 2024. (Source of photo: The Canadian Press/Justin Tang)

The long delay in confronting the threat posed by Qiu and Cheng might also be ascribed to what Gurski calls “inconvenient intelligence”. That is, CSIS warnings may have conflicted with the Liberal government’s pre-existing attitude towards China. Dealing head-on with Chinese espionage at the NML would likely have angered China, and caused it to retaliate, as it did in the Two Michaels affair. Australia similarly faced a devastating ban on coal exports to China after it raised concerns about Chinese spying. And the Liberals would have been very keen to avoid such unpleasantness.

By comparison, says Gurski, the U.S. and UK governments place a high value on their own counterintelligence programs and frequently take immediate and forceful action based on what their spy agencies tell them. This is not to say other countries haven’t also suffered from Chinese espionage efforts, or made mistakes in how they deal with such threats. But at least they are actively trying to defend themselves.

Spies Welcome

Despite the wealth of information included in the NML document dump, Leuprecht admits it is impossible to determine the true nature of Qiu and Cheng’s deception. They could have been sleeper agents of the sort featured in the TV series The Americans, inserted into Canadian society decades ahead of their mission. Or they might have been recruited only after gaining access to the highest levels of the NML. It is even possible they were simply naïve dupes manipulated by clever Chinese operatives into doing the bidding of the PLA under the guise of improving international scientific collaboration. Regardless, what stands out for Leuprecht is “the boldness with which they continued operating even after they’d been tipped off.”

One final mission: According to the declassified documents, Qiu (shown at top working at the NML) was aware she was being watched by her employer when she sent 30 vials of Ebola and Henipah virus samples to China’s Wuhan Institute of Virology in March 2019 prior to having her security clearance revoked. Shown, the devastating effects of Ebola in Guinea (bottom left) and Henipah in India (bottom right). (Sources of photos: (top) CBC; (bottom left) EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0; (bottom right) Sky News)

One final mission: According to the declassified documents, Qiu (shown at top working at the NML) was aware she was being watched by her employer when she sent 30 vials of Ebola and Henipah virus samples to China’s Wuhan Institute of Virology in March 2019 prior to having her security clearance revoked. Shown, the devastating effects of Ebola in Guinea (bottom left) and Henipah in India (bottom right). (Sources of photos: (top) CBC; (bottom left) EU Civil Protection and Humanitarian Aid, licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0; (bottom right) Sky News)

Of particular interest is that shipment of 30 vials of deadly Ebola and Henipah virus samples from the NML to the WIV on March 29, 2019. As the declassified CSIS files show, these materials were considered crucial to a research project at the WIV headed by Qiu. Yet at the time of the shipment, Qiu and Cheng already knew they were being watched; both had been interviewed about their security protocol habits by an independent investigator hired by the PHAC on February 15, 2019.

‘The message we are sending is that if you want to infiltrate a country, Canada is a great place to go,’ declares Leuprecht. ‘We are not particularly vigilant, and if we do catch you, we will let you leave the country so you can have a great career in China afterwards.’

“My guess,” says Leuprecht, “is that they got direction from Beijing to get whatever they could out of the lab and that they would be taken care of and rewarded.” Given how things turned out – with both Qiu and Cheng now living comfortably in China in high-profile academic positions under new names – it seems an entirely reasonable bit of speculation.

And it is this final twist that represents the most serious and longest-lasting blow delivered by the entire Qiu-Cheng affair: the signal to the world that Canada is a spy’s happy hunting grounds. Not only were Qiu and Cheng allowed to keep their security clearances for 10 months after being identified as possible threats, but they were also able to successfully complete their final task. And afterwards they left Canada for China – perhaps extracted is a better term – without any legal repercussions or sanctions. It is a tale that will resonate not just with agents on the hunt for sensitive information about viruses useful to China’s bioweapons plans, but anyone seeking to penetrate numerous other Canadian research facilities in the government, university and private sectors across a multitude of other key scientific and technological areas.

“The message we are sending is that if you want to infiltrate a country, Canada is a great place to go,” declares Leuprecht. “We are not particularly vigilant, and if we do catch you, we will let you leave the country so you can have a great career in China afterwards. If you were sitting in China reading through these 623 pages, you’d say to yourself, ‘Canada, that’s the country we’re going after.’”

“Canada is a great place to go”: The fact Qiu and Cheng returned to China without any legal repercussions sends a clear message to other foreign agents, says Leuprecht. “We are not particularly vigilant, and if we do catch you, we will let you leave the country.” Shown, a still from the 1963 movie The Great Escape starring Steve McQueen; unlike Qiu and Cheng, McQueen’s character failed in his escape attempt.

“Canada is a great place to go”: The fact Qiu and Cheng returned to China without any legal repercussions sends a clear message to other foreign agents, says Leuprecht. “We are not particularly vigilant, and if we do catch you, we will let you leave the country.” Shown, a still from the 1963 movie The Great Escape starring Steve McQueen; unlike Qiu and Cheng, McQueen’s character failed in his escape attempt.

Peter Shawn Taylor is senior features editor at C2C Journal. He lives in Waterloo, Ontario.

The Scientists Who Came in From the Cold: Canada’s National Microbiology Laboratory Scandal, Part I

espionage

The Scientists Who Came in From the Cold: Canada’s National Microbiology Laboratory Scandal, Part I

Published on May 18, 2024

From the C2C Journal

By Peter Shawn Taylor

In a breathless 1999 article on the opening of Canada’s top-security National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) in Winnipeg, the Canadian Medical Association Journal described the facility as “the place where science fiction movies would be shot.” The writer was fascinated by the various containment devices and security measures designed to keep “the bad boys from the world of virology: Ebola, Marburg, Lassa” from escaping. But what if insiders could easily evade all those sci-fi features in order to help Canada’s enemies? In the first of a two-part series, Peter Shawn Taylor looks into the trove of newly-unclassified evidence regarding the role of NML scientists Xiangguo Qiu and Keding Cheng in aiding China’s expanding quest for the study – and potential military use – of those virus bad boys.

Acclaimed spy novelist John Le Carré established his reputation with 1963’s The Spy Who Came in From the Cold. Set at the height of the Cold War, it describes an attempt by washed-up British spy Alec Leamas to infiltrate East German intelligence as a double agent. It’s a grim tale of hidden identities, uncertain alliances and spymasters prepared to sacrifice their own men in pursuit of bigger game. “We are witnessing the lousy end to a filthy, lousy operation,” Leamas snaps when he realizes how he’s been deceived by his own agency. According to Le Carré – who worked for Britain’s MI6 in Germany while writing the book – the world of espionage is unpleasant, unglamourous and devoid of loyalty. Unhappy endings are inevitable.

Despite its much-lauded air of verisimilitude, however, The Spy Who Came in From the Cold remains a work of fiction set in a now-distant past. And based on recent events in Canada, the current world of international espionage appears at sharp odds with Le Carré’s downbeat perspective. In fact, newly-unclassified documents tied to one of Canada’s biggest intelligence scandals suggest modern-day spies can live very happily ever-after.

No happy endings here: The Spy Who Came in From the Cold, spy novelist John Le Carré’s masterwork, depicts a gritty and amoral vision of modern espionage. Shown, a scene from the 1965 movie adaptation starring Richard Burton.

No happy endings here: The Spy Who Came in From the Cold, spy novelist John Le Carré’s masterwork, depicts a gritty and amoral vision of modern espionage. Shown, a scene from the 1965 movie adaptation starring Richard Burton.

This trove of once-secret material concerns the case of Xiangguo Qiu, an internationally-recognized scientist at Winnipeg’s National Microbiology Laboratory (NML), Canada’s highest-security biohazard facility, and her husband and fellow NML biologist Keding Cheng. Made public only after an unprecedented political struggle, the documents suggest Qiu had been doing the bidding of organizations linked to China’s military, possibly since 2016.

Using her security clearance, position and knowledge, Qiu transferred valuable information and materials out of the country – serving China’s interests while undermining those of Canada. The now-public material further suggests Qiu and Cheng took care to cover their tracks. As suspicions were raised about their activities, both lied and dissembled. And when their subterfuge was finally and fully revealed – but before Canada could be bothered to arrest them – they quietly escaped to China. Today they’re apparently living comfortably under new names while working in their preferred occupations. Here at home, the RCMP says it’s still investigating.

Qiu and Cheng, in other words, appear to have pulled off every spy’s dream: to accomplish their mission and get home safely while authorities sputter and fume comically on the other side of the border. As a recruiting ad for would-be agents, their tale succeeds brilliantly. If there is an unhappy ending to be found, it’s in the impact all this will have on Canada’s reputation as a vigilant and reliable ally.

A Curious Incident at the Lab

The NML is Canada’s only Level 4 Biosafety Lab (BSL4) and hence the only location in the country where deadly viruses such as Ebola, Henipah and Marburg along with other dangerous biological materials can be stored and studied. When the CBC first broke the story in July 2019 that RCMP officers had escorted Qiu, Cheng and their foreign research students out of the building and cancelled their security clearances, the Public Health Agency of Canada (PHAC), which oversees the NML, dismissed it as merely an “administrative matter” involving a breach of internal policy by staff.

Internationally-renowned virologist Xiangguo Qiu (top left) and her husband, biologist Keding Cheng (top right), both worked at Winnipeg’s National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) until they were escorted off the premises in July 2019 for what was initially described as an “administrative matter”. (Sources of photos: (top left) Public Policy Forum, licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0; (top right) Governor General’s Innovation Awards; (bottom) Trevor Brine/CBC)

Internationally-renowned virologist Xiangguo Qiu (top left) and her husband, biologist Keding Cheng (top right), both worked at Winnipeg’s National Microbiology Laboratory (NML) until they were escorted off the premises in July 2019 for what was initially described as an “administrative matter”. (Sources of photos: (top left) Public Policy Forum, licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0; (top right) Governor General’s Innovation Awards; (bottom) Trevor Brine/CBC)

At the time, Qiu was Head of Vaccines and Antivirals in the Zoonotic Diseases and Special Pathogens division of NML and internationally renowned for her work on Ebola. In 2018 she won a Governor General’s Innovation Award for co-developing a breakthrough treatment for the deadly virus. Cheng held a more junior position as a biologist at NML. Both were born in China and came to Canada to work in the 1990s; both are naturalized Canadian citizens.

A few weeks after Qiu and Cheng were removed from the NML, the Winnipeg Free Press reported on a mysterious March 2019 shipment of Ebola and Henipah virus samples from the NML to China. It had been organized by Qiu, and appeared to violate standard transfer protocols. In response, the PHAC again said there was nothing to be alarmed about. “The NML routinely shares samples of pathogens and toxins with laboratory partners in Canada and in other countries,” was the boilerplate response to all media inquiries. Further, the PHAC stated the virus shipment was “in response to a request” from an institute in China and that Qiu and Cheng’s “administrative investigation is not related to the shipment of virus samples to China.” There was, PHAC repeated, no connection between the two incidents.

Yet the possibility that Qiu and Cheng were involved in something other than an administrative matter piqued the interest of both media and opposition parties. Dogged investigative reporting turned up numerous problems inside the NML going back many years. The Winnipeg Free Press, for example, revealed significant security and safety concerns at the lab, including a petri dish containing tuberculosis culture that fell behind a work desk and lay undiscovered for a year; in 2009 a former NML researcher was caught at the U.S. border with 22 vials of biological material stolen from the lab – including some Ebola virus genes – hidden in a glove in his trunk.

Iain Stewart, head of the PHAC, was brought before the bar of Parliament and admonished for his refusal to release the requested documents, something that hadn’t happened to a federal civil servant in over a century.

As pressure mounted to explain what was really going on at the NML, in March 2021 the House of Commons’ Special Committee on the Canada-People’s Republic of China Relationship demanded evidence to support the contention that the case of Qiu and Cheng had no connection to national security matters. The Justin Trudeau government responded with a heavily-censored, 290-page collection of documents. Unhelpfully, whole pages were blacked out and many files were missing entirely. Of the legible material, most were media briefing notes and internal emails regarding the most mundane aspects of the 2019 virus shipment to China. (The declared value of 30 vials of some of the deadliest viruses in existence: $2.50 each.) Anything directly connected to Qiu and Cheng was redacted. The committee, comprised of an equal number of Liberal and opposition MPs, made a subsequent request, and when that didn’t work the House of Commons passed its own a motion demanding to see the full slate of uncensored documents.

Pressed hard to disclose the information, the federal Liberals dug in their heels, declaring it to be a matter of national security. In response, the House declared the government in contempt of Parliament. Iain Stewart, head of PHAC, was brought before the bar of Parliament and admonished for his refusal to release the requested documents, something that hadn’t happened to a federal civil servant in over a century. Stewart’s boss, Health Minister Patty Hadju, also refused to hand over any further documents, telling the Canada-China Committee “the information requested has both privacy and national security implications.” She also repeated the now-standard line that “there is no connection between the transfer of viruses…and the subsequent departure of these employees.”

Remarkably, even the Liberal-appointed Speaker of the House of Commons, Anthony Rota, took up the case, arguing that Parliament has an unfettered right to demand whatever it needs to do its job of holding the government to account. The Prime Minister’s Office in turn threatened to sue the Speaker in federal court, an unprecedented turn of events that prompted Rota to declare that the “Federal Court has no jurisdiction to restrict the House’s power to request documents.” What was shaping up to be a fascinating constitutional battle royale between the legislative and executive branches of government was rendered moot by the snap federal election of 2021.

After their re-election to another minority government, the Liberals had an apparent change of heart, perhaps due to legal advice that Rota’s position was unquestionable correct or, alternatively, a shift in personnel. Mark Holland, Hajdu’s replacement as health minister, agreed to make the documents available to an ad hoc committee consisting of one MP from each of the four main federal parties. Together with a panel of judges, the MPs were sworn to secrecy and allowed to examine the complete file in order to decide what documents were in the public’s interest to see and what should remain secret for national security reasons. The end result was a ground-breaking 623-page document released this past February.

A look behind the curtain: Made public in February 2024, the 623-page collection of formerly-classified documents includes (from left to right) a third-party investigation into Qiu and Cheng, secret “Canadian Eyes Only” reports from the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) and the pair’s own response to accusations made against them.

A look behind the curtain: Made public in February 2024, the 623-page collection of formerly-classified documents includes (from left to right) a third-party investigation into Qiu and Cheng, secret “Canadian Eyes Only” reports from the Canadian Security Intelligence Service (CSIS) and the pair’s own response to accusations made against them.

The package constitutes a remarkable collection of sensitive government files. It includes confidential internal investigations by the PHAC, secret “Canadian Eyes Only” reports by the Canadian Security and Intelligence Service (CSIS), Qiu and Cheng’s own responses to the accusations made against them, the official letters firing them and the government’s timeline of the entire saga. The level of disclosure is wide-ranging, although the names of most individuals are obscured. And while this cache of material still leaves many important questions unanswered, it provides a coherent – and deeply troubling – narrative for one of the most consequential breaches of Canada’s national security to have ever become public.

“Scientists need to do what scientists do”

John Williamson had a front-row seat to the entire Qiu-Cheng affair. As a member of the House of Commons’ Canada-China Committee prior to the 2021 election, the Conservative MP from New Brunswick was a participant in the raucous hearings and subsequent constitutional dust-up. “It was such a highly, highly unusual situation,” recalls Williamson in an interview. “For the RCMP to go into the lab and remove the scientists didn’t fit with initial government statements minimizing the situation. It had to be more than a personnel matter.”

As time passed and suspicions grew the government’s reasons for keeping the documents secret kept changing. “First it was privacy, then it was national security,” Williamson says. “The excuses were increasingly unconvincing.” The Canada-China Committee’s ultimate success in prying the documents out of a reluctant government’s hands is evidence, he says, that Parliament remains relevant despite the vast centralization of power in the Prime Minister’s Office.

Last year Williamson was selected as the Conservative representative to the ad hoc committee reviewing the classified material. Ensconced in a windowless room in a nondescript office building in downtown Ottawa under the watchful eye of Privy Council security guards, Williamson experienced the frisson of being among the first to read the documents once considered so dangerous the Liberals were prepared to sue the Speaker to avoid making them public.

“We were presented with the documents in chronological order,” Williamson recalls. “And as I read them, my understanding of the situation progressed in stages.” In the beginning, he wondered whether all the hoopla had been worth it. “My first impression,” he says, “was that this was a simply a badly-run laboratory.”

“For the RCMP to go into the lab and remove the scientists…it had to be more than a personnel matter,” says John Williamson, a Conservative MP from New Brunswick. Williamson was the only Conservative member on the ad hoc committee of four MPs given access to the entire file of classified documents ahead of their public release. (Source of photo: John Williamson)

“For the RCMP to go into the lab and remove the scientists…it had to be more than a personnel matter,” says John Williamson, a Conservative MP from New Brunswick. Williamson was the only Conservative member on the ad hoc committee of four MPs given access to the entire file of classified documents ahead of their public release. (Source of photo: John Williamson)

The initial entries explain that in August 2018 CSIS staff met with NML Scientific Director General Matthew Gilmour to discuss potential vulnerabilities. All federal high-security facilities regularly receive such “insider threat briefings.” At that meeting Qiu and Cheng were mentioned as possible subjects for further investigation. A preliminary review quickly revealed Qiu’s name on a Chinese-registered patent, in apparent violation of Canadian law; Cheng was also involved in several minor violations of security protocols. A more detailed investigation was ordered, including the clandestine “mirroring” (a form of external monitoring) of Qiu and Cheng’s computers and electronic devices, as well as formal interviews with the pair and their co-workers.

Williamson recalls thinking it ‘looked to be a made-in-Canada problem concerning public servants not following the rules. Management seemed quite lax and there was no effective oversight.’ An obvious problem, he thought, but not one with major national security implications.

This process revealed that Qiu and Cheng shared a surprisingly carefree attitude towards rules, an obvious problem given that they worked at Canada’s highest-level biosafety research lab. Cheng deliberately mislabelled sensitive biological material as “kitchen utensils” to circumvent necessary transportation precautions. He also improperly downloaded data onto removable storage devices and was involved in several curious incidents at the building’s front desk involving the comings and goings of his research students, most of whom had links to China.

In an interview with a third-party investigator hired by the PHAC, Qiu’s standard reply to any security concerns was that she was solely focused on research and considered excessive rule-following to be an impediment to her work. “Scientists need to do what scientists do,” was her common refrain. At other times she pointed a finger at the PHAC’s poor training practices. Cheng met bothersome security requirements with a similar shrug.

“Scientists need to do what scientists do”: Initial investigations by the PHAC and CSIS revealed that Qiu and Cheng shared a surprisingly carefree attitude towards security rules, despite working in Canada’s only Level 4 Biosafety Laboratory. Shown, Qiu at work in her Winnipeg lab. (Source of photo: CBC)

“Scientists need to do what scientists do”: Initial investigations by the PHAC and CSIS revealed that Qiu and Cheng shared a surprisingly carefree attitude towards security rules, despite working in Canada’s only Level 4 Biosafety Laboratory. Shown, Qiu at work in her Winnipeg lab. (Source of photo: CBC)

Initially taking this evidence at face-value, Williamson recalls thinking it “looked to be a made-in-Canada problem concerning public servants not following the rules. Management seemed quite lax and there was no effective oversight.” An obvious problem, he thought, but not one with major national security implications.

Following the third-party investigation of Qiu and Cheng, CSIS weighed in with its own report on the two scientists dated April 9, 2020. This includes observations that Qiu was involved in joint research with officials from China’s Academy of Military Medical Sciences, the People’s Liberation Army’s (PLA) top medical research institution. As a matter of national security, CSIS makes specific note of the PLA’s plans for improving its chemical and biological warfare capabilities. Another item of concern was an NML researcher – identified as “Individual 2” in the documents – who attempted to remove ten vials of material from the NML lab. Individual 2 would later be revealed to be a senior technician from the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV) working in partnership with Qiu.

The plot unfolds: The first CSIS investigation revealed that Qiu had conducted joint research with scientists at China’s Academy of Military Medical Sciences (shown). Despite this worrisome connection, CSIS was initially reluctant to categorize Qiu as a security risk. (Source of photo: N509FZ, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0)

The plot unfolds: The first CSIS investigation revealed that Qiu had conducted joint research with scientists at China’s Academy of Military Medical Sciences (shown). Despite this worrisome connection, CSIS was initially reluctant to categorize Qiu as a security risk. (Source of photo: N509FZ, licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0)

“As you dig deeper into the documents, you begin to realize mainland China military officials may have infiltrated the lab,” recalls Williamson. “Now it looks like we could have a clandestine espionage operation meant to remove information and Canadian lab officials are just missing it. Now we have a national security problem.”

Despite these initial warning signs, CSIS was initially reluctant to accuse Qiu of anything nefarious. While observing she had a flexible concept of loyalty towards Canada and seemed unconcerned about security procedures, the report states, “The Service does not have a reason to suggest that Ms. QIU would willingly cooperate with a foreign power knowing harm would come to Canada.” Here the matter nearly ended.

According to the federal timeline of events on April 13, 2020 – nearly a year-and-a-half after concerns were first raised about Qiu and Cheng – PHAC management was preparing to close the investigation. Reprimand letters for the pair were drafted. Sanctions against the pair were to include “disciplinary measures and training”, but they would keep their jobs and security clearances. A week later, however, this reprimand process was “paused due to new information related to external investigation.”

Complete Collapse of Canada’s National Security Interests

On April 20, 2020, CSIS reopened its files on Qiu and Cheng as a result of “newly discovered information”. Where this information came from is not revealed, and has likely been kept hidden by the ad hoc committee. It could be the result of continuing CSIS investigations, or it could have been provided by the intelligence service of an allied country. Regardless of its provenance, CSIS immediately lost confidence in Qiu’s loyalty to Canada due to her “close and clandestine relationships with a variety of entities of the People’s Republic of China.”

“When you get to the later CSIS documents, you begin to realize how huge the issue really is,” says Williamson. “Now not only do you have People’s Republic of China people in the labs, but Canadian citizens are working as agents for mainland China. At this point I realized I was looking at a complete collapse of Canada’s national security interests – this is why the government didn’t want to release the documents.”

CSIS reopened its investigation into Qiu and Cheng after “newly discovered information” cast doubt on Qiu’s loyalty to Canada due to her “close and clandestine relationships with a variety of entities of the People’s Republic of China.”

CSIS reopened its investigation into Qiu and Cheng after “newly discovered information” cast doubt on Qiu’s loyalty to Canada due to her “close and clandestine relationships with a variety of entities of the People’s Republic of China.”

The additional information comprises the meat of the unredacted material and contains many alarming subplots. The most damning is the existence of numerous applications filled out in the name of Qiu and Cheng for China’s notorious “talent” programs. In accordance with China’s ambitions to globally dominate certain technologies and scientific fields, talent programs offer generous rewards to Chinese researchers in western countries who can bring that knowledge home by whatever means. There are hundreds of talent programs throughout China operating at all levels of government, the most famous being the national Thousand Talents Program (TTP). According to FBI research, “talent programs usually involve undisclosed and illegal transfers of information, technology, or intellectual property.” They are, in other words, thinly-veiled espionage operations.

Applications for talent programs originate with Chinese institutions and are then offered to targeted individuals before being approved by the “foreign expert affairs bureau” of the requisite level of government. One TTP application made out in Qiu’s name offered to provide up to $1 million in research funding plus preferential health care and taxation benefits. Another offered her a salary of $15,000 per month for time spent in China, plus $30,000 per year while she was outside the country. This income would be in addition to her day job with the Government of Canada. Cheng was also named in applications for regional talent programs. To be clear, the documents do not conclusively prove Qiu or Cheng were participants in any talent programs, just that there were application forms filled out in their names by various Chinese institutions. And that both Qiu and Cheng knew about this.

A talent for espionage: According to the FBI, China’s many “talent” programs usually involve “undisclosed and illegal transfers of information, technology, or intellectual property” from western countries to China.

A talent for espionage: According to the FBI, China’s many “talent” programs usually involve “undisclosed and illegal transfers of information, technology, or intellectual property” from western countries to China.

What is crystal clear is that Qiu’s skills and position were very attractive to Chinese institutions making talent applications in her name. One particularly eager suitor was the WIV. This facility is now infamous for its proximity to the epicentre of the global outbreak of Covid-19 and its possible role as the source of the SARS CoV-2 virus. The WIV also has a long track record of collaboration with Chinese military researchers, as a 2023 report by the U.S. Office of the Director of National Intelligence explains. Back in 2018, however, the WIV had just become China’s first BSL4 lab (also referred to as P4) and needed someone with experience to help it develop protocols befitting its new status and to get some new research projects up and running.

According to documents summarized in a June 30, 2020 CSIS report, the WIV said it considered Qiu to be “the only highly experienced Chinese expert available internationally, who is still fighting on the front lines for a P4 laboratory.” Beyond Qiu’s much-needed experience and know-how, the WIV also wanted her help in gaining access to a supply of deadly viruses necessary for its future research plans. At the time, U.S. export restrictions denied China easy access to these materials and, according to the CSIS summary, Qiu’s participation with the WIV was considered “beneficial for…importing the P4 virus research resources from abroad.”

It was these comments, Williamson says, that brought his reading of the classified material to a full stop as the problems at the NML came into sharp focus. “Here was a Chinese institution stating plainly that Qiu was the only Chinese scientist available who could feed their ambitions. She was Beijing’s greatest asset in a Level 4 lab in any western nation.”

‘We are in the process of applying for the official permit to transfer BSL4 pathogens from Canada to China. To avoid confusing the leaders, it is better not to let National Microbiology Laboratory know about this project.’

Qiu made five trips to China in 2017 and 2018. In October 2018 she visited Wuhan and made a side trip to the WIV to lead a workshop on biosafety for 30 staff scientists. This event was not recorded in the official itinerary she filed with her Canadian employer. The same month the WIV formally requested the transfer of 30 vials of Ebola and other deadly viruses from the NML, a transaction overseen by Qiu. Recall that both PHAC and former federal Health Minister Hajdu repeatedly declared this shipment to be unrelated to the “administrative matter” of Qiu and Cheng being escorted off the premises of NML. Given what we now know, that seems very unlikely.

Based on the document dump, it appears Qiu was aggressively recruited by the Wuhan lab, possibly with the encouragement of a TTP, to participate in several sensitive and potentially-controversial research projects. What is referred to as WIV Project 1 included developing “mouse-adapted and guinea pig-adapted Ebola viruses”. Key to this project was a selection of virus samples identical to those ultimately provided by the NML in March 2019 through Qiu’s efforts. Reinforcing the secretive nature of the relationship between Qiu and the WIV, the project’s plan states: “We are in the process of applying for the official permit to transfer BSL4 pathogens from Canada to China. To avoid confusing the leaders, it is better not to let National Microbiology Laboratory know about this project.” Qiu seems to have done as she was told. CSIS reports “PHAC was not aware of this project.”

“The only highly experienced Chinese expert available”: CSIS uncovered documents revealing that Qiu was considered essential to the research ambitions of the Wuhan Institute of Virology (shown), an institution with close ties to the Chinese military and infamous for its proximity, and likely connection, to the initial outbreak of Covid-19. (Source of photo: AP Photo/Ng Han Guan)

“The only highly experienced Chinese expert available”: CSIS uncovered documents revealing that Qiu was considered essential to the research ambitions of the Wuhan Institute of Virology (shown), an institution with close ties to the Chinese military and infamous for its proximity, and likely connection, to the initial outbreak of Covid-19. (Source of photo: AP Photo/Ng Han Guan)

The weight of evidence suggests Qiu was a vital link in China’s apparently successful strategy to enhance its biological research capabilities using information and materials taken from Canada’s highest security biohazard lab. And it appears this type of subterfuge was ongoing for a considerable period of time. Documentation for an award presented to Qiu in 2016 by China’s Academy of Military Medical Sciences and obtained by CSIS says Qiu “used Canada’s Level 4 Biosecurity Laboratory as a base to assist China to improve its capability to fight highly-pathogenic pathogens…and achieve brilliant results.”

A subsequent CSIS report delves deeper into the background of the many research students and other scientists associated with the Chinese regime that cultivated connections with Qiu and Cheng during their time at the NML. Among these characters is Shi Zhengli, the WIV deputy-director widely referred to as “bat-woman” for her focus on bat virus research at the WIV prior to the Covid-19 outbreak. Shi is identified as “Individual 1” in the CSIS files. Another frequent Qiu collaborator was Major-General Chen Wei, named China’s “top biowarfare expert” by a U.S. congressional investigation. CSIS similarly describes Chen – identified as “Major General, PLA/Top Virologist AMMS (Chief 2)” in the at-times easily-broken code of the documents – as “China’s chief biological weapons defense expert engaged in research related to biosafety, bio-defence and bio-terrorism.”

Another name that pops up frequently is Feihu Yan. He is described in academic papers as being associated with the Institute for Military Veterinary at China’s Academy of Military Medical Sciences, as well as Canada’s NML and the University of Manitoba. In the declassified CSIS documents, Feihu is referred to as “Restricted Visitor 4”, which means he had access to NML’s BSL4 lab under Qiu’s supervision. Qiu and Feihu appear as co-authors on ten research papers published in a variety of scientific journals from 2016 through 2021. Over the same period, Qiu and Chen co-authored two papers. All the research concerns deadly viruses such as Ebola and Rift Valley fever.

Bosom buddies: Shi Zhengli, WIV’s deputy-director and often referred to as “bat-woman” (left), and Major-General Chen Wei, China’s “top biowarfare expert” (right), frequently collaborated with Qiu during her time at the NML. (Source of left photo: Chinatopix via AP, File)

Bosom buddies: Shi Zhengli, WIV’s deputy-director and often referred to as “bat-woman” (left), and Major-General Chen Wei, China’s “top biowarfare expert” (right), frequently collaborated with Qiu during her time at the NML. (Source of left photo: Chinatopix via AP, File)

As the CSIS documentation makes clear, this research has both civil and military applications and is of considerable interest to China’s PLA. Among the Academy of Military Medical Science’s tasks, CSIS observes, is “the development of military biotechnologies, biological counter-terrorism and prevention and control of major diseases.” As for China’s greater goals, then-U.S. Director of National Intelligence John Ratcliffe caused a stir in 2020 with a Wall Street Journal commentary about the threats posed by China’s talent programs and its use of scientific research stolen from western countries. Referring specifically to its biowarfare ambitions, Ratcliffe said China had “conducted human testing on members of the People’s Liberation Army in hope of developing soldiers with biologically enhanced capabilities.” In an ominous coda, he warned “There are no ethical boundaries to Beijing’s pursuit of power.”

Espionage? Never Heard of it

CSIS’s evolving investigation into Qiu and Cheng established numerous situations in which they attempted to keep their deep links with China’s scientific and military establishments hidden. As early as 2016, for example, Qiu held multiple positions at Chinese universities which she left off her Canadian CVs. She also had her name scrubbed from the online program of a 2017 conference in Wuhan at which she gave a talk. And there are the gaps in her travel itineraries and the secrecy surrounding the 2019 virus shipment. Cheng’s work seems equally cloaked in mystery. According to CSIS, he had been conducting a three-year research program at the NML on behalf of China’s Centre for Disease Control – without NML management’s knowledge.

Scrubbed clean: Qiu held multiple positions at Chinese universities as early as April 2016, but hid these facts from PHAC management and lied about them in her initial interview with CSIS.

Scrubbed clean: Qiu held multiple positions at Chinese universities as early as April 2016, but hid these facts from PHAC management and lied about them in her initial interview with CSIS.

Confronted with evidence of their deceptions, Qiu and Cheng adopted differing tactics to explain away their behaviour. In a November 26, 2020 written response to the accusations against her, Qiu took on the aura of a workaholic, politically-clueless scientist. “Please let me express my sincere gratitude to you and PHAC administration for the opportunity and consideration on the clarifications of the [security] report,” her letter begins. She then claimed, “It was only during the investigative interview that I started to know some new words to me, such as ‘NATO’, ‘Spy’ and ‘espionage’.” Qiu further insisted that, “I have dedicated almost all my time to the beauty of science through hardworking and national and international collaborations, no TV watching, no time to take vacations.”

Qiu maintained this façade of the dedicated-if-naïve scientist throughout the investigation. When confronted with contrary evidence, such as TPP applications filled out in her name, her central role in WIV Project 1, an undeclared bank account in China, unrecorded trips to the WIV and so on, she repeatedly claimed it was a mistake or the result of her poor grasp of English. It was not always a convincing tactic. Pressed to explain the presence of “Restricted Visitor 1” in her lab, an individual who held a Chinese public affairs passport and had clear ties to the Chinese military through bioweapons expert Major-General Chen, Qiu claimed not to know anything about her. It was later revealed Restricted Visitor 1 had rented a house owned by Qiu and Cheng when she was in Winnipeg.

“There are no ethical boundaries to Beijing’s pursuit of power”: Former U.S. Director of National Intelligence John Ratcliffe raised the alarm about China’s biowarfare ambitions in 2020, noting that China has “conducted human testing on members of the People’s Liberation Army in hope of developing soldiers with biologically enhanced capabilities.” (Source of photo: Texas A&M University-Commerce Marketing Communications Photography, licensed under CC BY 2.0)

“There are no ethical boundaries to Beijing’s pursuit of power”: Former U.S. Director of National Intelligence John Ratcliffe raised the alarm about China’s biowarfare ambitions in 2020, noting that China has “conducted human testing on members of the People’s Liberation Army in hope of developing soldiers with biologically enhanced capabilities.” (Source of photo: Texas A&M University-Commerce Marketing Communications Photography, licensed under CC BY 2.0)

In his own letter in response to PHAC’s investigation, Cheng took a more pragmatic approach to explaining his actions. When presented with a talents form in his name that required the applicant to declare they “passionately love the socialist motherland”, he observed that applying for jobs was a very Canadian thing to do, and that he was simply “putting bread and butter on the table.” Maintaining a healthy income was often central to Cheng’s responses.

When these efforts didn’t dissuade the investigators, the couple launched a union grievance claiming racial discrimination. In an August 5, 2020 complaint, Qiu and Cheng alleged they were “treated differently and more severely than other employees” because of their Chinese background, and that this was an example of “racial profiling.” This accusation of racism appears to have added two months to the investigative process. After being identified as potential security risks as early as September 2019, it wasn’t until January 19, 2021 that Qiu and Cheng were both formally stripped of their security clearances and fired.

Adherence to numerous human resources procedures, union-erected obstacles and sensitivity towards the feelings of the alleged spies – even after it was well-established they were “not being truthful” – largely explains why it took so long to finally fire them. Much of the federal timeline’s 14 pages (what is called the “Investigative Critical Path”) depicts an investigation bogged down by protocols and rules. There is little hint of urgency. “Conduct the interviews in a respectful and professional manner,” reads one entry advising investigators to avoid upsetting Qiu and Cheng. “Care will be taken to avoid any comments or behaviours that could intimidate or be perceived as badgering.” This approach continued right through to the letters firing them. “I appreciate that this may be a stressful time, and remind you that the Employee Assistance Program is available 24 hours a day, 7 days a week,” their identical termination letters conclude. Such velvet-glove treatment seems absurd given the obvious threat they posed to Canada’s national security.

WIV got its hands on its desired collection of deadly viruses thanks to the efforts of Qiu, who also provided invaluable expertise and advice on the operation of its BSL4 lab. WIV Project 1 was presumably a great success.

And while the investigation did ultimately remove Qiu and Cheng from the NML, the message embedded in their fate is hardly one of deterrence. After all, the pair were never arrested and charged, let alone tried, convicted and imprisoned. In nearly all countries throughout history, the penalty for espionage has been death. In Communist China today, it still is.

Instead, according to a Globe and Mail investigation, they are now enjoying comfortable lives back in China. Qiu seems particularly active in her chosen field, with four Chinese patents filed since 2020, suggesting she has been carrying on an active research agenda after being removed from the NML. Two of these patents are with the WIV, two with the prestigious University of Science and Technology of China. Cheng appears to be employed as a professor of biology at Guangzhou Medical University; in 2021 and 2022 he was identified as an immunologist at KingMed Diagnostics, a Chinese-based testing laboratory.