Indigenous

Putting government mismanagement of Indigenous affairs in the rear-view mirror

From the Macdonald-Laurier Institute (MLI)

By Ken Coates for Inside Policy

The failures of governance on Indigenous affairs represents an unhappy situation where the problem is, simultaneously, too much government and too little governance

In an era of a mounting number of interconnected complex and difficult problems, one feels sorry for the politicians and civil servants attempting to produce policies, programs, and funding that will make real and sustained progress. We are often confronted with the frightening realization that government, as it is currently structured and directed, is simply not up to the challenges of the 21st century. This is certainly the case with Indigenous affairs in Canada, where the federal government struggles to find the right path forward.

The socio-economic data is clear. Indigenous peoples lag well behind the non-Indigenous population on almost all measures: personal income, access to clean water, educational outcomes, rates of incarceration, health outcomes, opioid deaths, tuberculosis cases, overcrowded homes, and many others. Language loss is endemic, many communities struggle with intergenerational conflict, too many cultural traditions are at risk, and long-term systemic poverty continues to take its toll.

Most Canadians think that the government of Canada is doing a great deal – some people think too much – to address Indigenous challenges and opportunities. They point, as the government often does, to billions of dollars in annual expenditures, formal and public apologies, major court judgments in favour of Indigenous defendants, a seat at a growing number of political tables, and concessions on language, values, and priorities.

The juxtaposition of these two realities is troubling – despite the massive expenditures on Indigenous affairs there are continued and major shortcomings in First Nations, Métis, and Inuit outcomes and achievements. Frustration burns deep in many Indigenous communities, as it does among the general population. Canadians at large have heard the many apologies, hundreds of program announcements, billions in spending, and the near-constant uncertainty of legal processes, and they too are deeply concerned about the failure of decades of concerted government efforts to make things better.

Of course, there have been major achievements. While media coverage focuses on conflict and despair, First Nations, Inuit, and Métis communities have made substantial improvements, even with the current difficulties in mind. Post-secondary attendance remains strong, with continuing challenges with the high school to PSE transition. Indigenous entrepreneurship is a bright spot in the Canadian economy. Modern treaties and self-government agreements are changing how the government manages Indigenous policies, funding, and decision-making. And impact and benefit agreements have secured Indigenous communities an important place in resource and infrastructure development.

But frustrations with the government of Canada’s management of Indigenous affairs continues. Communities complain of long-delayed negotiations, difficulties with payments, the omnipresent influence of the Indian Act, files lingering on the desk of the Minister of Indigenous Services Canada, the inability to get promised money out the door quickly and efficiently, the imposition of complicated accountability provisions, and many other problems. Even major settlements, like the $40 billion allocated to address shortcomings in child and family services, has been bogged down in unrewarding negotiations.

The failures of governance on Indigenous affairs represents an unhappy situation where the problem is, simultaneously, too much government and too little governance. Starting well before Confederation, paternalism became the hallmark of federal policy towards Indigenous peoples. Government officials believed that they knew best and managed Indigenous affairs with scant consideration of Indigenous ideas and goals – and often with a firm, manipulative hand. To the degree that Indigenous peoples escaped the dominance of Ottawa, it was largely due to the shortage of government workers and money, which meant that most northern peoples were left largely alone until the 1950s.

In the 1950s and 1960s, in a massive wave of self-justified paternalism, government intervention expanded rapidly. Indigenous peoples were required to live in government-established and run settlements, typically in government-built houses and under the control of a growing cadre of paternalistic Indian Agents. Residential and day school education became standard fare – as did acute language loss and the disruption of harvesting activity and traditional cultures. Welfare dependency, extremely rare before the mid-1950s, replaced harvesting and the mixed economy as the economic foundations of Indigenous life, with all of the controls and intrusions that attend any reliance on government cheques.

Well-meaning state officials inherited the paternalism of their predecessors, believing that government-designed and -run programs would provide Indigenous communities with pathways to the mainstream economy and the benefits of the dominant society. A few achievements stand out, but generally the effort did not work. Indigenous communities were transformed into frustrated supplicants, relying on a steady stream of applications and approval processes to provide what were typically short-term grants that would fund core community operations.

The arrangements prioritized federal budget-making and administration over Indigenous decision-making and community priority-setting. The budgets grew dramatically. Federal officials made countless announcements. The number of federal civil servants grew dramatically. And individual Indigenous people continued to suffer. Through decades in which state funding and programming continued to expand, the gap between Indigenous well-being and non-Indigenous social and economic conditions scarcely narrowed at all. What did grow dramatically was social dysfunction, self-harm, and family disarray.

It turned out that too much government “help” could be as bad as neglect and inattention to Indigenous needs. Ottawa continued to supply earnest and well-meant programs, but they were built with diminishing enthusiasm from Indigenous peoples. First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities understood what the government of Canada did not: that community control was much more important and effective than Ottawa-centred policy-making. Much of the Indigenous effort since the 1970s has focused on righting the imbalance, establishing more self-government processes, expanding own-source revenues, and returning to Indigenous peoples the autonomy that had sustained them for centuries.

Indigenous peoples have their own agendas – and they have largely succeeded in changing the core foundations of Indigenous governance in Canada. Modern treaties have, for some people, eliminated some of the more pernicious aspects of the Indian Act and its associated bureaucracies. Self-governing First Nations are become more common and increasingly successful. The Inuit secured their own territory – Nunavut – and acquired considerable autonomy in Labrador and northern Quebec. Impact and benefit agreements and resource revenue sharing have given communities the funding they require to establish their own spending priorities. Duty-to-consult and accommodate provisions have given Indigenous communities a major role in determining the shape and nature of resource development. Major Supreme Court of Canada decisions continue to extend Indigenous authority.

This story of Indigenous re-empowerment has not yet fully unfolded, although the returns to date have been more than promising. Self-governing First Nations in the Canadian North and elsewhere have used their autonomy to very good effect. Communities near the oil sands in Alberta have used their involvement in resource extraction to create substantial autonomy for themselves. Near-urban and urban First Nations are supporting metropolitan redevelopment. Joint ventures and economic cooperation have become the norm rather than the exception. Struggles continue; generations of paternalism and government oversight are not overcome in a flash.

But the primary lesson is simple. State paternalism has been a force for disruption and manipulation of Indigenous communities. Re-empowerment, autonomy, and economic independence have demonstrated the potential to rebuild, enhance, and strengthen First Nations, Métis, and Inuit communities. Decades of government mismanagement of Indigenous affairs must be put in the rear-view mirror. It is time for the re-empowerment of Indigenous communities to become the new normal.

Indigenous realities have changed dramatically, particularly related to Indigenous rights, expectations, capacity, financial settlements and community expectations. Government administration and policy-making, as current constituted, is not sufficiently community-centric, properly funded, appropriately responsive or driven by Indigenous imperatives. Despite generations of large-scale spending and many programs and announcements, basic conditions are far too often seriously substandard and real progress slow and unimpressive. With Indigenous people and their governments in the forefront, Indigenous governance and support requires a dramatic rethinking and Indigenous empowerment in order to respond properly to the challenges and opportunities of the 21st century.

Ken Coates is a Distinguished Fellow and Director of Indigenous Affairs at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute and a Professor of Indigenous Governance at Yukon University

Frontier Centre for Public Policy

Budget 2024 as the eve of 1984 in Canada

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

Those who claim there are unmarked burials have painted themselves into a corner. If there are unmarked burials, there have had to be murders because why else would anyone attempt to conceal the deaths?

The Federal Government released its Budget 2024 last week. In addition to hailing a 181% increase in spending on Indigenous priorities since 2016, “Budget 2024 also proposes to provide $5 million over three years, starting in 2025-26, to Crown-Indigenous Relations and Northern Affairs Canada to establish a program to combat Residential School denialism.” Earlier this spring, the government proclaimed:

The government anticipates the Special Interlocutor’s final report and recommendations in spring 2024. This report will support further action towards addressing the harmful legacy of residential schools through a framework relating to federal laws, regulations, policies, and practices surrounding unmarked graves and burials at former residential schools and associated sites. This will include addressing residential school denialism.

Like “Reconciliation,” the exact definition of what the Federal government means by “residential school denialism” is not clear. In this vague definition, there is, of course, a potential for legislating vindictiveness.

What further action is needed to address “the harmful legacy of residential schools” except to enforce a particular narrative about the schools as being only harmful? Is it denialism to point out that many students, such as Tomson Highway and Len Marchand, had positive experiences at the schools and that their successful careers were, in part, made possible by their time in residential school? If the study of history is subordinated to promoting a particular political narrative, is it still history or has it become venal propaganda?

Since the sensational May 27, 2021, claim that 215 children’s remains had been found in a Kamloops orchard, the Trudeau government has been chasing shibboleths. The Kamloops claim remains unsubstantiated to this day in two glaring ways: no names of children missing from the Kamloops IRS (Indian Residential Schools) have been presented and no human remains have been uncovered. For anyone daring to point out this absence of evidence, their reward is being the target of a witch hunt. As we recently witnessed in Quesnel, B.C., to be labeled as a residential school denialist is to be drummed out of civil society.

If we must accept a particular political narrative of the IRS as the history of the IRS, does our freedom of conscience and speech have any meaning?

To the discredit of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, fictions of missing and murdered children circulating long before the Commission’s inception were subsumed by the TRC (Truth and Reconciliation Commission). Unmarked graves and burials were incorporated into the TRC’s work as probable evidence of foul play. In the end, the TRC found no evidence of any murders committed by any staff against any students throughout the entirety history of the residential schools. Unmarked graves are explained as formerly marked and lawful graves that had since become lost due to neglect and abandonment. Unmarked burials, if they existed, could be construed as evidence of criminal acts, but such burials associated with the schools have never been proven to exist.

Those who claim there are unmarked burials have painted themselves into a corner. If there are unmarked burials, there have had to be murders because why else would anyone attempt to conceal the deaths? If there are thousands of unmarked burials, there are thousands of children who went missing from residential schools. How could thousands of children go missing from schools without even one parent, one teacher, or one Chief coming forward to complain?

There are, of course, neither any missing children nor unmarked burials and the Special Interlocutor told the Senate Committee on Indigenous People: “The children aren’t missing; they’re buried in the cemeteries. They’re missing because the families were never told where they’re buried.”

Is it denialism to repeat or emphasize what the Special Interlocutor testified before a Senate Committee? Is combating residential school denialism really an exercise in policing wrongthink? Like the beleaguered Winston in Orwell’s 1984, it is impossible to keep up with the state’s continual revision of the past, even the recent past.

For instance, the TRC’s massive report contains a chapter on the “Warm Memories” of the IRS. Drawing attention to those positive recollections is now considered “minimizing the harms of residential schools.”

In 1984, the state sought to preserve itself through historical revision and the enforcement of those revisions. In the Trudeau government’s efforts to enforce a revision of the IRS historical record, the state is not being preserved. How could it be if the IRS is now considered to be a colossal genocide? The intent is to preserve the party in government and if it means sending Canada irretrievably down a memory hole as a genocidaire, so be it.

Michael Melanson is a writer and tradesperson in Winnipeg.

Frontier Centre for Public Policy

The Smallwood solution

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

All Canadians deserve decent housing, and indigenous people have exactly the same legal right to house ownership, or home rental, as any other Canadian. That legal right is zero.

$875,000 for every indigenous man, woman and child living in a rural First Nations community. That is approximately what Canadian taxpayers will have to pay if a report commissioned by the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) is accepted. According to the report 349 billion dollars is needed to provide the housing and infrastructure required for the approximately 400,000 status Indians still living in Canada’s 635 or so First Nations communities. ($349,000,000,000 divided by 400,000 = ~$875,000).

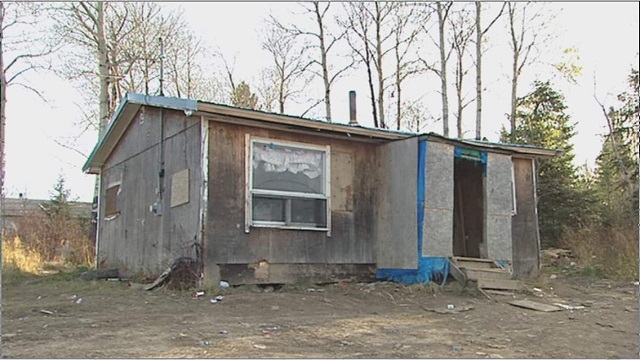

St Theresa Point First Nation is typical of many of such communities. It is a remote First Nation community in northern Manitoba. CBC recently did a story about it. One person interviewed was Christina Wood, who lives in a deteriorating house with 23 family members. Most other people in the community live in similar squalor. Nobody in the community has purchased their own house, and all rely on the federal government to provide housing for them. Few people in the community have paid employment. Those that do have salaries that come in one way or another from the taxpayer.

But St. Theresa Point is a growing community in the sense that birth rates are high, and few people have the skills or motivation needed to be successfully employed in Winnipeg, or other job centres. Social pathologies, such as alcohol and other drug addictions are rampant in the community. Suicide rates are high.

St. Theresa Point is one of hundreds of such indigenous communities in Canada. This is not to say that all such First Nations communities are poor. In fact, some are wealthy. Those lucky enough to be located in or near Vancouver, for example, located next to oil and gas, or on a diamond mine do very well. Some, like Chief Clarence Louis’ Osoyoos community have successfully taken advantage of geography and opportunity and created successful places where employed residents live rich lives.

Unfortunately, most are not like that. They look a lot more like St. Theresa Point. And the AFN now says that 350 billion dollars are needed to keep those communities going.

Meanwhile, all of Canada is in the grip of a serious housing crisis. There are many causes for this, including the massive increase in new immigrants, foreign students and asylum seekers, all of whom have to live somewhere. There are various proposals being considered to respond to this problem. None of those plans come anywhere near to suggesting that $875,000 of public funds should be spent on every Canadian man, woman or child who needs housing. The public treasury would not sustain such an assault.

All Canadians deserve decent housing, and indigenous people have exactly the same legal right to house ownership, or home rental, as any other Canadian. That legal right is zero. Our constitution does not give Canadians – indigenous or non-indigenous- any legal right to publicly funded home ownership, or any right to publicly funded rental property. And no treaty even mentions housing. In all cases it is assumed that Canadians – indigenous and non-indigenous – will provide for themselves. This is the brutal reality. We are on our own when it comes to housing. There are government programs that assist low income people to buy or rent homes, but they are quite limited, and depend on a person qualifying in various ways.

But indigenous people do not have any preferred right to housing. The chiefs and treaty commissioners who signed the treaties expected indigenous people to provide for their own housing in exactly the same way that all other Canadians were expected to provide for their own housing. In fact, the treaty makers, chiefs and treaty commissioners – assumed that indigenous people would support themselves just like every other Canadian. There was no such thing as welfare then.

Our leaders today face difficult decisions about how to spend limited public funds to try and help struggling Canadians find adequate housing in which to raise their families, and get to and from their places of employment. Indigenous Canadians deserve exactly as much help in this regard as everyone else. Finding sensible, affordable ways to do this is vitally important if Canada is to thrive.

And one of hundreds of these difficult and expensive housing decisions our leaders must deal with now is how to respond to this new demand for 350 billion dollars – a demand that would result in indigenous Canadians receiving hundreds of times more housing help than other Canadians.

Our leaders know that authorising massive spending like that in uneconomic communities is completely unfair to other Canadians – for one thing doing so means that there would be no money left for urban housing assistance. They also know that pouring massive amounts of money into uneconomic, dysfunctional communities like St. Theresa’s Point – the “unguarded concentration camps” Farley Mowat described long ago- only keeps generations of young indigenous people locked in hopeless dependency.

In short, they know that the 350 billion dollar demand makes no sense.

Our leaders know that, but they won’t say that. In fact it is not hard to predict how politicians will respond to the 350 billion dollar demand. None of their responses will look even remotely like what I have written above. Instead, they will say soothing things, while pushing the enormous problem down the road. Eventually, when forced by circumstances to actually make spending decisions they will provide stopgap “bandage” funding. And perhaps come up with pretend “loan guarantee” schemes – loans they know will never be repaid. Massive loan defaults in the future will be an enormous problem for our children and grandchildren. But today’s leaders will be gone by then.

So, in a decade or so communities, like St. Theresa Point, will still be there. Any new housing that has been built will already be deteriorating and inadequate. The communities will remain dependent. The young people will be trapped in hopeless dependency.

And the chiefs will be making new money demands.

At some point this country will have to confront the reality that most of Canada’s First Nations reserves, particularly the remote ones, are not sustainable. Better plans to educate and provide job skills to the younger generations in those communities, and assist them to move to job centres, will have to be found. Continuing to pretend that this massive problem will sort itself out by passing UNDRIP legislation, or pretending that those depressed communities are “nations” is only delaying the inevitable.

When Joey Smallwood told the Newfoundland fishermen, who had lived in their outports for generations, that they must move for their own good, there was much pain. But the communities could no longer support themselves, and it had to be done. Entire communities moved. It worked out.

The northern First Nations communities are no different. The ancestors of the residents of those communities supported themselves by fishing and hunting. It was an honourable life. But it is gone. The young people there now will have to move, build new lives, and become self-supporting like their ancestors.

Brian Giesbrecht, retired judge, is a Senior Fellow at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

-

espionage2 days ago

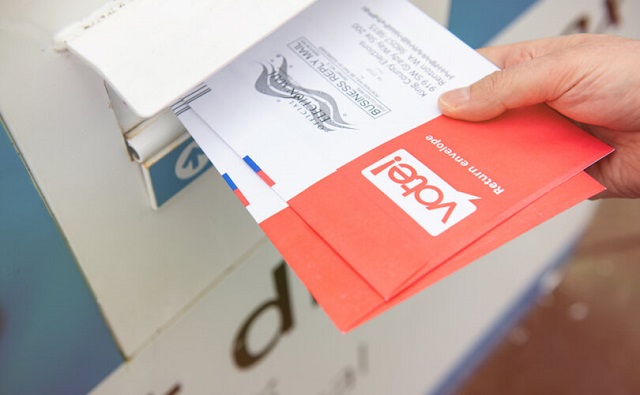

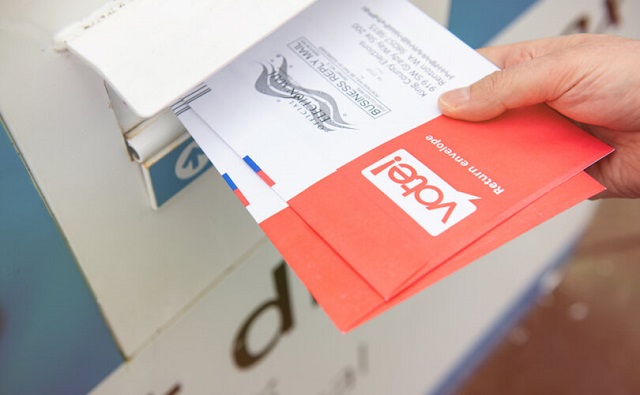

espionage2 days agoOne in five mail-in voters admitted to committing voter fraud during 2020 election: Rasmussen poll

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoHonda deal latest episode of corporate welfare in Ontario

-

Automotive1 day ago

Automotive1 day agoThe EV ‘Bloodbath’ Arrives Early

-

CBDC Central Bank Digital Currency20 hours ago

CBDC Central Bank Digital Currency20 hours agoA Fed-Controlled Digital Dollar Could Mean The End Of Freedom

-

Brownstone Institute19 hours ago

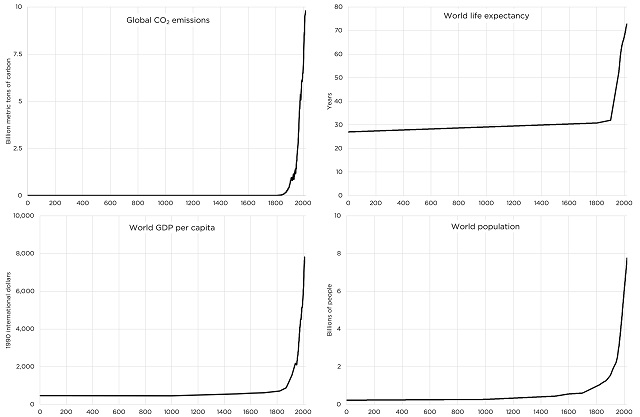

Brownstone Institute19 hours agoThe Numbers Favour Our Side

-

Frontier Centre for Public Policy16 hours ago

Frontier Centre for Public Policy16 hours agoHow much do today’s immigrants help Canada?