Health

Patient List Growing At The Brent Sutter Sports Medicine Clinic – Part 1 Of 2

By Sheldon Spackman

Dr. Keith Wolstenholme says the goal of their team at the Brent Sutter Sports Medicine Clinic is to get patients the fastest possible return to regular function and they’re having terrific success.

Patients coming to the Brent Sutter Sports Medicine Clinic suffering muscle pain from any activity related injury in their shoulders, ankles, knees, hips, elbows, or wrists will initially see a physiotherapist for an assessment at a cost of $100. The physiotherapist will assess the injury and either prescribe a recovery plan or arrange for the patient to see one of the clinic’s doctors or surgeons.

Dr Wolstenholme says Central Albertans should know about the Brent Sutter Clinic because it could be a quicker route to seeing a specialist. Since early last year the Brent Sutter Sports Medicine Clinic has served over 800 patients. Most have been referred by other health care providers but Dr Wolstenholme says a growing number of patients are deciding to come in on their own seeking a quicker return from their injury.

For more information you can find their website at: www.brentsuttersportsmedicine.ca

Business

National dental program likely more costly than advertised

From the Fraser Institute

By Matthew Lau

At the beginning of June, the Canadian Dental Care Plan expanded to include all eligible adults. To be eligible, you must: not have access to dental insurance, have filed your 2024 tax return in Canada, have an adjusted family net income under $90,000, and be a Canadian resident for tax purposes.

As a result, millions more Canadians will be able to access certain dental services at reduced—or no—out-of-pocket costs, as government shoves the costs onto the backs of taxpayers. The first half of the proposition, accessing services at reduced or no out-of-pocket costs, is always popular; the second half, paying higher taxes, is less so.

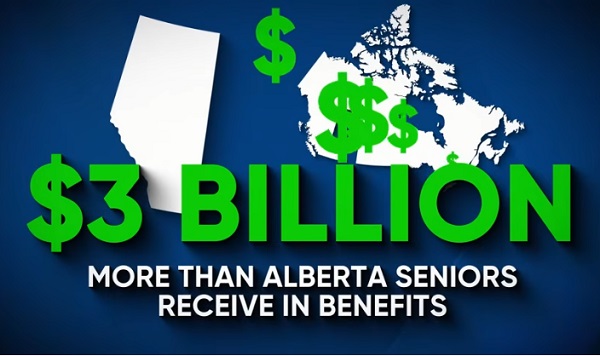

A Leger poll conducted in 2022 found 72 per cent of Canadians supported a national dental program for Canadians with family incomes up to $90,000—but when asked whether they would support the program if it’s paid for by an increase in the sales tax, support fell to 42 per cent. The taxpayer burden is considerable; when first announced two years ago, the estimated price tag was $13 billion over five years, and then $4.4 billion ongoing.

Already, there are signs the final cost to taxpayers will far exceed these estimates. Dr. Maneesh Jain, the immediate past-president of the Ontario Dental Association, has pointed out that according to Health Canada the average patient saved more than $850 in out-of-pocket costs in the program’s first year. However, the Trudeau government’s initial projections in the 2023 federal budget amounted to $280 per eligible Canadian per year.

Not all eligible Canadians will necessarily access dental services every year, but the massive gap between $850 and $280 suggests the initial price tag may well have understated taxpayer costs—a habit of the federal government, which over the past decade has routinely spent above its initial projections and consistently revises its spending estimates higher with each fiscal update.

To make matters worse there are also significant administrative costs. According to a story in Canadian Affairs, “Dental associations across Canada are flagging concerns with the plan’s structure and sustainability. They say the Canadian Dental Care Plan imposes significant administrative burdens on dentists, and that the majority of eligible patients are being denied care for complex dental treatments.”

Determining eligibility and coverage is a huge burden. Canadians must first apply through the government portal, then wait weeks for Sun Life (the insurer selected by the federal government) to confirm their eligibility and coverage. Unless dentists refuse to provide treatment until they have that confirmation, they or their staff must sometimes chase down patients after the fact for any co-pay or fees not covered.

Moreover, family income determines coverage eligibility, but even if patients are enrolled in the government program, dentists may not be able to access this information quickly. This leaves dentists in what Dr. Hans Herchen, president of the Alberta Dental Association, describes as the “very awkward spot” of having to verify their patients’ family income.

Dentists must also try to explain the program, which features high rejection rates, to patients. According to Dr. Anita Gartner, president of the British Columbia Dental Association, more than half of applications for complex treatment are rejected without explanation. This reduces trust in the government program.

Finally, the program creates “moral hazard” where people are encouraged to take riskier behaviour because they do not bear the full costs. For example, while we can significantly curtail tooth decay by diligent toothbrushing and flossing, people might be encouraged to neglect these activities if their dental services are paid by taxpayers instead of out-of-pocket. It’s a principle of basic economics that socializing costs will encourage people to incur higher costs than is really appropriate (see Canada’s health-care system).

At a projected ongoing cost of $4.4 billion to taxpayers, the newly expanded national dental program is already not cheap. Alas, not only may the true taxpayer cost be much higher than this initial projection, but like many other government initiatives, the dental program already seems to be more costly than initially advertised.

Business

RFK Jr. says Hep B vaccine is linked to 1,135% higher autism rate

From LifeSiteNews

By Matt Lamb

They got rid of all the older children essentially and just had younger children who were too young to be diagnosed and they stratified that, stratified the data

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) found newborn babies who received the Hepatitis B vaccine had 1,135-percent higher autism rates than those who did not or received it later in life, Robert F. Kennedy Jr. told Tucker Carlson recently. However, the CDC practiced “trickery” in its studies on autism so as not to implicate vaccines, Kennedy said.

RFK Jr., who is the current Secretary of Health and Human Services, said the CDC buried the results by manipulating the data. Kennedy has pledged to find the causes of autism, with a particular focus on the role vaccines may play in the rise in rates in the past decades.

The Hepatitis B shot is required by nearly every state in the U.S. for children to attend school, day care, or both. The CDC recommends the jab for all babies at birth, regardless of whether their mother has Hep B, which is easily diagnosable and commonly spread through sexual activity, piercings, and tattoos.

“They kept the study secret and then they manipulated it through five different iterations to try to bury the link and we know how they did it – they got rid of all the older children essentially and just had younger children who were too young to be diagnosed and they stratified that, stratified the data,” Kennedy told Carlson for an episode of the commentator’s podcast. “And they did a lot of other tricks and all of those studies were the subject of those kind of that kind of trickery.”

But now, Kennedy said, the CDC will be conducting real and honest scientific research that follows the highest standards of evidence.

“We’re going to do real science,” Kennedy said. “We’re going to make the databases public for the first time.”

He said the CDC will be compiling records from variety of sources to allow researchers to do better studies on vaccines.

“We’re going to make this data available for independent scientists so everybody can look at it,” the HHS secretary said.

— Matt Lamb (@MattLamb22) July 1, 2025

Health and Human Services also said it has put out grant requests for scientists who want to study the issue further.

Kennedy reiterated that by September there will be some initial insights and further information will come within the next six months.

Carlson asked if the answers would “differ from status quo kind of thinking.”

“I think they will,” Kennedy said. He continued on to say that people “need to stop trusting the experts.”

“We were told at the beginning of COVID ‘don’t look at any data yourself, don’t do any investigation yourself, just trust the experts,”‘ he said.

In a democracy, Kennedy said, we have the “obligation” to “do our own research.”

“That’s the way it should be done,” Kennedy said.

He also reiterated that HHS will return to “gold standard science” and publish the results so everyone can review them.

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCanada’s loyalty to globalism is bleeding our economy dry

-

Agriculture2 days ago

Agriculture2 days agoCanada’s supply management system is failing consumers

-

armed forces1 day ago

armed forces1 day agoCanada’s Military Can’t Be Fixed With Cash Alone

-

Alberta24 hours ago

Alberta24 hours agoAlberta Next: Alberta Pension Plan

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoCOVID mandates protester in Canada released on bail after over 2 years in jail

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoTrump transportation secretary tells governors to remove ‘rainbow crosswalks’

-

Business1 day ago

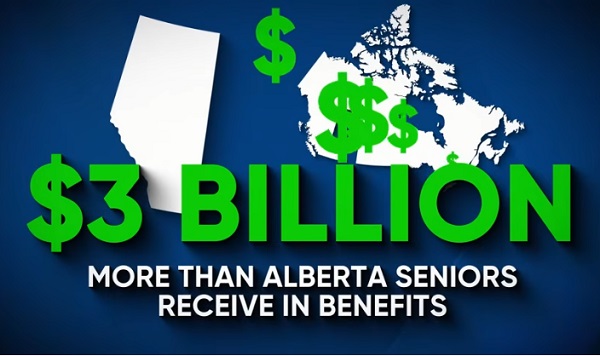

Business1 day agoCarney’s spending makes Trudeau look like a cheapskate

-

Crime2 days ago

Crime2 days agoProject Sleeping Giant: Inside the Chinese Mercantile Machine Linking Beijing’s Underground Banks and the Sinaloa Cartel