Addictions

New documentary exposes safer supply as gateway to teen drug use

By: Alexandra Keeler

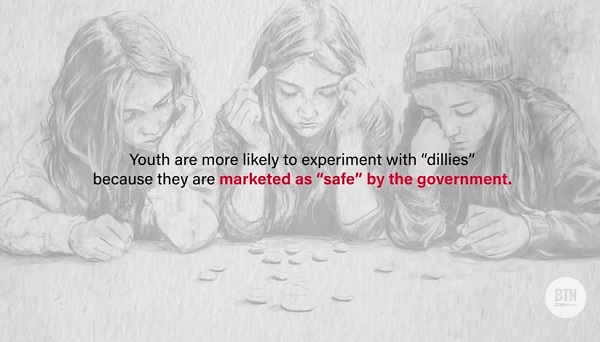

In a new documentary, Port Coquitlam teens describe how safer supply drugs are diverted to the streets, contributing to youth drug use

Madison was just 15 when she first encountered “dillies” — hydromorphone pills meant for safer supply, but readily available on the streets.

“Multiple people walking up the street, down the street, saying ‘dillies, dillies,’ and that’s how you get them,” Madison said, referring to dealers in Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside.

Madison says she could get pills for $1.25 each, when purchased directly from someone receiving the drugs through safer supply — a provincial program that provides drug users with prescribed opioids. Madison would typically buy a whole bottle to last a week.

But as her tolerance grew, so did her addiction, leading her to try fentanyl.

“The dillies weren’t hitting me anymore … I tried [fentanyl] and instantly I just melted,” she said.

Kamilah Sword, Madison’s best friend, was just 14 when she died of an overdose on Aug. 20, 2022 after taking a hydromorphone pill dispensed through safer supply.

Madison, along with Kamilah’s father, Gregory Sword, are among the Port Coquitlam, B.C., residents featured in a documentary by journalist Adam Zivo. The film uncovers how safer supply drugs — intended as a harm reduction measure — contribute to harm among youth by being highly accessible, addictive and dangerous.

Through emotional interviews with teens and their families, the film links these drugs to overdose deaths and explores how they can act as a gateway to stronger substances like fentanyl.

Some last names are omitted to respect the victims’ desire for privacy.

Subscribe for free to get BTN’s latest news and analysis, or donate to our journalism fund.

‘Not a myth’

Safer supply aims to reduce overdose deaths by providing individuals with substance use disorders access to pharmaceutical-grade alternatives, such as hydromorphone.

But some policy experts, health officials and journalists are concerned these drugs are being diverted onto the streets — particularly hydromorphone, which is often sold under the brand name Dilaudid and nicknamed “dillies.”

Zivo, the film’s director, points out the disinformation surrounding safer supply diversion, highlighting that some drug legalization activists downplay the issue of diversion.

In 2023, B.C.’s then-chief coroner Lisa Lapointe dismissed claims that individuals were collecting their safer supply medications and selling them to youth, thereby creating new opioid dependencies and contributing to overdose deaths. She labeled such claims an “urban myth.”

In the film, Madison describes how teen substance users would occasionally accompany people enrolled in the safer supply program to the pharmacy, where they would fill their prescriptions and then sell the drugs to the teens.

“It’s not a myth, because my best friend died from it,” she says in the film.

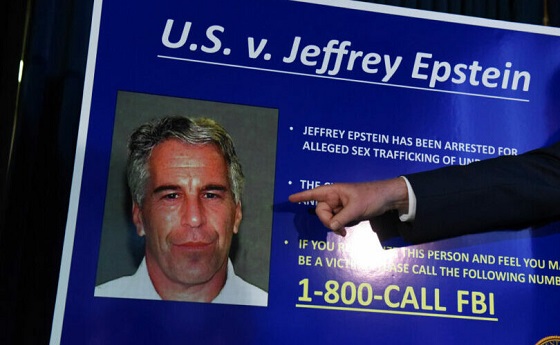

Fiona Wilson, deputy chief of the Vancouver Police Department, testified on April 15 to the House of Commons health committee studying Canada’s opioid crisis that about 50 per cent of hydromorphone seizures by police are linked to safer supply.

|

Deputy Chief of the Vancouver Police Department, Fiona Wilson, testified on April 15 during the House of Commons ‘Opioid Epidemic and Toxic Drug Crisis in Canada’ health committee meeting.

Additionally, Ottawa Police Sergeant Paul Stam previously confirmed to Canadian Affairs that similar reports of diverted safer supply drugs have been observed in Ottawa.

“Hopefully, by giving these victims a platform and bringing their stories to life, the film can impress upon Canadians the urgent need for reform,” Zivo told Canadian Affairs.

‘Creating addicts’

The teens featured in the film share their experiences with the addictive nature of dillies.

“After doing them for like a month, it felt like I needed them everyday,” says Amelie North, one teen featured in the documentary. “I felt like I couldn’t stand being alive without being on dillies.”

Madison explains how tolerance builds quickly. “You just keep doing them until it’s not enough at all.”

Madison started using fentanyl at the age of 12, leading to a near-fatal overdose after just one hit at a SkyTrain station. “It took five Narcan kits to save my life,” she says in the film.

Many of her friends use dillies or have tried fentanyl, she says. She estimates half the students at her school do.

“Government-supplied hydromorphone is a dangerous domino in the cascade of an addict’s downward spiral to ever more risky behaviour,” said Madison’s mother, Beth, to Canadian Affairs.

“The safe drug supply is creating addicts, not helping addicts,” Denise Fenske, North’s mother, told Canadian Affairs.

“I’m not sure when politicians talk about all the beds they have opened up for youth with drug or alcohol problems, where they actually are and how do we access them?”

Sword, Kamilah’s father, expressed his concern in an email to Canadian Affairs. “I want the people [watching the film] to understand how easy this drug is to get for the kids and how many kids it is affecting, the pain it causes the loved ones, [with] no answers or help for them.”

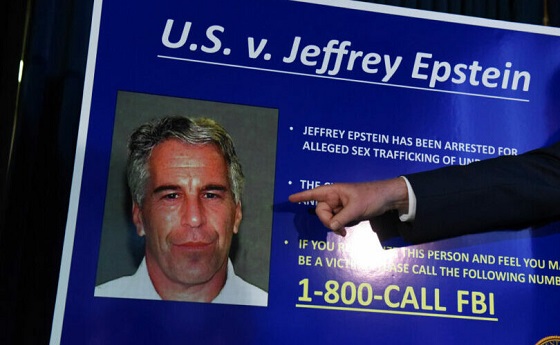

|

Screenshot: Dr. Matthew Orde reviewing Kamilah Sword’s toxicology report during his interview for the filming of ‘Government Heroin 2: The Invisible Girls’ in March 2024.

Autopsy

Kamilah’s death raises further concerns.

According to Dr. Matthew Orde, a forensic pathologist featured in the film, Kamilah’s toxicology report revealed a mix of depressants and stimulants, including flualprazolam (a benzo), benzoylecgonine (a cocaine byproduct), MDMA and hydromorphone.

Orde criticizes the BC Coroners Service for not following best practices by focusing solely on cardiac arrhythmia caused by cocaine and MDMA, while overlooking the potential role of benzos and hydromorphone.

Orde notes that in complex poly-drug deaths, an autopsy is typically performed to determine the cause more accurately. He says he was shocked that Kamilah’s case did not receive this level of investigation.

B.C. has one of the lowest autopsy rates in Canada.

Zivo told Canadian Affairs he thinks a public inquiry into Kamilah’s case and other youth deaths involving hydromorphone since 2020 is needed to assess if the province is accurately reporting the harms of safer supply.

“That just angers me that our coroners did not do what most of Canada would have done,” Sword told Canadian Affairs.

“It also makes me question why they didn’t do an autopsy, what is our so-called government hiding?”

Government Heroin 2: The Invisible Girls is available for free on YouTube.

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Subscribe to Break The Needle. Our content is always free – but if you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism, consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

Addictions

From opioids to office: An interview with Alberta’s new addiction minister

By Alexandra Keeler

Rick Wilson shares what led him into — and out of — addiction, his goals for Alberta’s recovery model and the value of an ‘Indigenous lens’

In mid-May, Alberta appointed Rick Wilson as the province’s new minister of mental health and addiction.

Wilson, who represents the Maskwacîs-Wetaskiwin riding south of Edmonton, was Alberta’s longest serving minister of Indigenous relations, serving from 2019 to this year.

Now, Wilson is tasked with accelerating the implementation of the Alberta Model, a recovery-oriented system of care that prioritizes addiction prevention, early intervention and treatment over harm reduction.

Canadian Affairs spoke with Wilson about his priorities in the new role, how his prior work with Indigenous communities shapes his perspective and what lies ahead for mental health and addiction care in Alberta.

AK: I understand you’ve been tasked with advancing the Alberta Recovery Model. What aspects of the model require the most focus in the term ahead?

RW: My goal is going to be to keep the momentum going. [We need to] get all the recovery communities opened up, keep expanding our supports, like CASA Classrooms [classroom-based mental health programs], and just keep filling the gaps for better information.

AK: Why was your predecessor, Dan Williams, shuffled out of the post?

It was a cascading event. Our speaker took a job in Washington, so we voted for a new speaker, Rick McIver. That left a hole in Municipal Affairs, [where Dan was moved]. I’d been bugging Premier Smith for more help with addictions and mental health. She said, ‘Go fix it then, I’ll put you there.’

AK: Do you have personal experience with mental health or addiction struggles?

RW: Do you want the whole sad story here?

I used to raise a lot of cattle and had one really rank bull that was terrorizing the farm. One morning I tried to get him up, and it didn’t end well — he got me down, fractured several vertebrae in my neck and back, and collapsed my lungs. I don’t know how I survived, but somehow I did.

For a year, I couldn’t walk. I was in so much pain I didn’t even know who I was. I would literally pray for one second of relief. Whatever the doctor gives you, you’ll take it — Oxytocin to Percocet; you name it, I was on it. My wife said she’d give me a pill and an hour later, I’d be begging her for more. This went on for close to a year.

I finally had what’s called laser spinal surgery. I was one of the very lucky ones. I went into it in a wheelchair, but I came out walking, and the pain was gone.

About a week later, I told my wife, ‘I think I’m full of infection — I’m burning up with fever, I’m sweating, and I think they’ve nicked a nerve. I feel like I got a giant hole in me.’ She looked at me like I was crazy.

We went to the doctor. He said I was completely healed and asked, ‘What do they have you on?’ Then he said, ‘You just quit taking everything?’ I told him, ‘Yeah, there’s no more pain, so I just quit.’

He said, ‘Well, you’re in withdrawal.’

Once I knew what it was, I was able to tough it out, but it’s not a pleasant experience. I don’t think people are really trying to get high — you just don’t want to feel that alone. I literally felt like there was a hole right through me, like I was just empty inside. So I have a lot of empathy for people that are in addiction.

Rick Wilson was sworn in as the Minister of Mental Health and Addictions on May 16. | Rick Wilson via Facebook

RW: When I was in Indigenous Relations, half my time was spent around addiction issues. It’s horrible. Out on the First Nations, there’s hardly a chief who hasn’t lost a son or somebody close to them. That’s all I did — go to funerals, one after another.

What I learned was you really just have to listen — and that’s one thing the government isn’t good at.

AK: What learnings from that role are you bringing to your new portfolio, and how do you see them benefiting your work in mental health and addiction?

RW: I want to put an Indigenous lens on the whole thing. I think that’s the piece we’re missing. What I found most successful was to use their culture. Get the elders involved. They have the sweats, smudges and language. To take somebody’s language away is devastating.

You hear a lot about reconciliation, but I took it for real. My good friend Willie Littlechild said, ‘Minister, I want to see some reconcili-action.’ He said I could use that — so I do, a lot.

AK: Can Indigenous recovery models work more broadly for non-Indigenous Albertans?

RW: I’ve really seen it work with non-Indigenous folks as well. But everybody’s going to be different. For some people, maybe Christianity is the way to go. And for some people, it’s Alcoholics Anonymous.

I think [the common thread] is that hope. [When you’re addicted] you feel hopeless.

I felt empty, and you need something to replace that emptiness. The problem is, you turn to alcohol, you turn to drugs to fill that gap, and that’s not going to do it. It’s a very temporary fix that just pushes you deeper down the rabbit hole.

Minister Rick Wilson celebrates the Pigeon Lake Regional School Class of 2025 on May 25. | Rick Wilson via Facebook

AK: Can you explain what a recovery community is, and how it fits into the province’s continuum of care?

RW: The way they used to do it, you’d throw someone in recovery for a couple of weeks [and expect] that should cure it, then out you go. Well, that doesn’t work.

[Now] it’s more of a holistic approach: you go into detox, and then from there, you go into rehab. Some people fall out of rehab, [but they go] back into detox, and eventually you start working your way around the circle.

Transitional housing is key. You can’t just send someone back into the community without support — they’ll relapse. After housing, the focus is on community reintegration, finding work, and family support. It’s like an Indigenous healing circle — a full circle to prevent falling back into addiction.

We’re working on 11 sites — one in Red Deer, Gunn, Lethbridge and Calgary opening this summer. Seven more are planned, including Edmonton, Grande Prairie and five with Indigenous communities.

AK: Some critics argue that the Alberta Model leans toward coercive care, and that the benefits of involuntary treatment may not outweigh the risks and costs. How will the Compassionate Intervention Act, which mandates addiction treatment, address those concerns?

RW: Compassionate care isn’t just for the individuals [with substance use disorders]. We have to be compassionate for them, but we also have to be compassionate for the people in their community that are impacted.

In my own riding in the Maskwacîs-Wetaskiwin — some people come in [to the hospital] three times in a day that have overdosed. To overdose several times a day — you’re doing brain damage when you’re at that point.

These people are in dire straits, and we have to intervene with them, because they’re not even capable of thinking for themselves [or] to go for voluntary treatment. We want to give the people that are addicted that opportunity to rebuild their lives. Right now, there’s just a lot of enabling going on.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Addictions

After eight years, Canada still lacks long-term data on safer supply

By Alexandra Keeler

Canada has spent more than $100 million on safer supply programs, but has failed to research their long-term effects

Canada lacks long-term data on safer supply programs, despite funding these programs for years.

Safer supply programs dispense pharmaceutical opioids as a replacement for toxic street drugs.

There is a growing body of research on safer supply’s short-term health effects. But there are no Canadian studies that evaluate program participants’ health impacts beyond 18 months.

The absence of research into long-term data on safer supply means policymakers do not understand how safer supply affects participants’ health, substance use or social outcomes over time.

“Long-term data is important because it helps us understand not just short-term health outcomes like reduced overdoses, but also broader impacts on quality of life, stability and health care use,” said Farihah Ali, scientific lead at the Institute for Mental Health Policy Research at CAMH. The Centre for Addiction and Mental Health is one of Canada’s leading centres for addiction research and clinical care.

Pilot projects

Canada’s first safer supply programs were introduced in Ontario in 2016. Those programs were initially small in scope, intended for a small group of high-risk individuals.

In 2020, the federal government began funding safer supply pilot programs across the country. Provinces are responsible for the delivery and regulation of these programs.

B.C. introduced provincewide programs in 2021. Other provinces, such as Alberta, have restricted safer supply access to a very small number of clinics, and have generally shifted away from harm reduction models in favour of recovery-oriented approaches.

According to the Canadian Public Health Association, an advocacy organization, the original goal for safer supply was to reduce deaths and harms associated with the unregulated toxic drug supply. It was not meant to replace addiction treatment, but to rather act as a bridge to further care.

However, a 2023 report by researchers at McMaster University and Simon Fraser University noted safer supply “does not principally operate toward goals of treatment or recovery.” The report describes safer supply instead as an emergency intervention focused on stabilization and survival.

Evidence gaps

There is a small but growing body of short-term studies on the health effects of Canada’s safer supply programs. Most only track participants’ outcomes for up to 12 months.

Some of those studies suggest safer supply may reduce the immediate harms associated with drug use.

A 2024 study found a 91 per cent reduction in the risk of death among high-risk individuals receiving safer supply in B.C. Critics have raised concerns about the study’s methodology, sample size and confounding variables.

In contrast, a March study suggested B.C.’s safer supply and decriminalization policies may be associated with increased hospitalizations. These findings also sparked controversy, with experts debating how well the data isolate causal impacts.

And a comparative study released in April also showed some positive outcomes from safer supply. It too sparked significant expert debate.

‘Arms-length’

Of all the provinces, B.C. has implemented safer supply most broadly. The province’s health ministry did not directly respond when asked about the long-term goals of its safer supply program, or whether B.C. collects longitudinal data on program participants’ health outcomes.

“Evidence shows [safer supply] helps separate people from the unregulated drug supply, manage their substance use and withdrawal symptoms with regulated medications, and helps connect them to voluntary health and social supports,” a Ministry of Health spokesperson told Canadian Affairs in an email.

The ministry did not provide the evidence it referenced.

At the federal level, Health Canada confirmed that, to date, it has funded just two evaluations of safer supply programs, despite spending more than $100 million on safer supply since April 2023.

The first was a short-term study, funded by the federal government’s Substance Use and Addictions Program program. Conducted over four months, that study assessed 10 safer supply programs in Ontario, B.C., and New Brunswick. It documented initial impacts on participants’ lives and program delivery, primarily through qualitative methods such as interviews and surveys.

The second study is an ongoing, “arms-length evaluation” of 11 safer supply pilot programs funded by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR), Canada’s federal health research agency.

When asked about long-term research on safer supply, Health Canada referred Canadian Affairs to a 2022 funding announcement about this multi-year evaluation. While the evaluation is being conducted over several years, it is unclear if it includes long-term tracking of patients’ outcomes.

Barriers and resistance

There are a number of factors that make it challenging to evaluate safer supply programs over long periods.

Ali, of CAMH, says unstable, short-term funding can disrupt long-term research.

“When programs are shut down or scaled back, we lose contact with participants and the ability to track outcomes over time,” she said.

Program participants can also be difficult to track over long periods, she says. Many struggle with housing insecurity, health instability and criminalization.

Frontline staff also face burnout and high turnover, she says, limiting support for such research activities.

Additionally, there are tradeoffs between the anonymity needed to encourage patients to access safer supply programs and the ability to collect detailed data.

“Ethical concerns — like not wanting to burden participants or risk their safety or confidentiality — require us to design studies that are trauma-informed and flexible, which adds complexity to long-term data collection,” Ali said.

Julian Somers, a clinical psychologist and professor at Simon Fraser University, says B.C.’s failure to conduct long-term evaluations of its safer supply programs is not just an oversight, but an act of negligence.

“B.C. has some of the best pharmaceutical data systems in the world,” Somers said, referring to PharmaCare and PharmaNet — databases that capture every prescription drug transaction in the province.

Somers says his team previously used PharmaNet data to examine prescribed opioids’ effects on health and social outcomes. In 2017, he proposed a long-term safer supply evaluation using these tools.

In 2017, he proposed a long-term evaluation of B.C.’s safer supply programs.

The province declined.

According to Ali, “Future research should explore how safer supply impacts people’s long-term health, stability and connection to care.”

“We also need to listen to people’s experiences, how safer supply affects their daily lives, their sense of dignity, and their relationships with care providers through qualitative mechanisms.”

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

-

Immigration2 days ago

Immigration2 days agoUnregulated medical procedures? Price Edward Islanders Want Answers After Finding Biomedical Waste From PRC-Linked Monasteries

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoDemocracy Watchdog Says PM Carney’s “Ethics Screen” Actually “Hides His Participation” In Conflicted Investments

-

Addictions2 days ago

Addictions2 days agoAfter eight years, Canada still lacks long-term data on safer supply

-

Bruce Dowbiggin1 day ago

Bruce Dowbiggin1 day agoHow Did PEI Become A Forward Branch Plant For Xi’s China?

-

COVID-191 day ago

COVID-191 day agoJapan disposes $1.6 billion worth of COVID drugs nobody used

-

National2 days ago

National2 days agoLiberals push to lower voting age to 16 in federal elections

-

International13 hours ago

International13 hours agoThis ends now: Trump orders Bondi to unseal Epstein grand jury testimony

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoUpgrades at Port of Churchill spark ambitions for nation-building Arctic exports