Addictions

Governments ease alcohol access as evidence of its harms mount

By Alexandra Keeler

From cancer to heart disease to brain damage, the evidence of alcohol’s harms is mounting. So why are governments making it easier to drink?

In May, shortly after Parliament resumed, Quebec Senator Patrick Brazeau introduced Bill S-202, a private member’s bill to require nearly all alcoholic beverages to carry health warning labels.

“As a former alcohol consumer, I was once in the 75 per cent of Canadians who are not aware that there is a causal link between alcohol consumption and seven cancers,” Brazeau told the House of Commons on June 3.

“I personally battled colon cancer several years ago, so much so that when I received treatment, I felt I was being killed inside.”

Brazeau is something of an outlier in government. Public health experts say Canadian governments are not doing enough to address alcohol’s known health risks — and that the alcohol industry is a big part of the problem.

“We’ve known about the carcinogenic effects of alcohol since the 80s,” said Peter Butt, a University of Saskatchewan researcher and co-chair of Canada’s latest drinking guidelines. “But there are no warning labels, so the consumer is given false confidence.

“Some of this falls at the doorstep of the government, because they regulate the labeling.”

Alcohol harms

Today, the World Health Organization warns that alcohol harms nearly every system in the body.

The International Agency for Research on Cancer classifies alcohol as a cause of six cancers.

Chronic alcohol use raises the risks of liver and heart disease, brain damage, mental health issues, injuries and fetal alcohol spectrum disorders.

In Canada, the federal government oversees labeling and public health messaging rules, while the provinces control liquor sales and drinking ages.

In January 2023, Health Canada released updated national alcohol guidelines in response to the growing evidence of alcohol-related harms. This new guidance marked a major departure from its 2011 recommendations, which had suggested women not exceed 10 drinks per week and men not exceed 15.

The new guidelines have a sober message: no amount of alcohol is risk-free, and risk rises significantly with more than two drinks a week.

“We didn’t say you shouldn’t drink more than two standard drinks a week. We said you should reduce the amount that you drink,” said Butt, who co-chaired the team that updated the guidelines.

“The consumer had a right to know.”

Mixed messages

Aside from tightening its guidelines, Canadian governments have done little to better protect the public.

Public health experts say one major flashpoint has been warning labels. In general, drinks with greater than 0.5 per cent alcohol content are exempt from standard food and beverage labeling requirements.

“Even bottled water or non-alcoholic beer has to have the nutrition facts because it doesn’t have enough alcohol in it to get the exemption,” said Adam Sherk, a research scientist at the Canadian Centre for Substance Use and Addiction who also advised on Canada’s updated alcohol guidelines.

The Canadian Cancer Society has been advocating for labels on alcohol products since 2017. The Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research has done the same since 2023. But Health Canada has not initiated any regulatory process to mandate warning labels for alcohol products.

Some research indicates such labels could reduce sales.

A 2020 study by the Yukon government and the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research tested how warning labels affect consumer behaviour. It found labels did increase awareness and reduce sales.

Yukon pulled its label requirements after the alcohol industry threatened to sue the government.

Convenient

Labelling is just one of many measures governments could take to reduce alcohol-related harm.

In addition to labels, the Canadian Alcohol Policy Evaluation project recommends minimum unit pricing, marketing and advertising controls, and public education campaigns. No province or territory has fully implemented all of these measures.

“[T]he Canadian federal government has not adopted or only partially adopted many evidence based alcohol policies,” the project’s report reads.

Meanwhile, some provinces are moving in the opposite direction.

Nova Scotia is considering expanding retail options. In April, Quebec rejected a recommendation to lower its blood alcohol limit for drivers, despite repeated coroner warnings.

Ontario has gone the furthest.

The province plans to invest $175 million over five years to grow its alcohol sector. It has begun permitting alcohol sales in convenience stores for the first time — with up to 8,500 new retailers expected to carry alcohol by 2026. It has also scrapped previous limits on pack sizes and discount pricing.

In April 2024, the province’s chief medical officer, Dr. Kieran Moore, recommended raising the legal drinking age from 19 to 21. Premier Doug Ford rejected the idea, arguing that if 18-year-olds can enlist in the military, they should be allowed to drink.

“We believe in treating people like adults,” he told media at the time.

In late June, the province also approved alcohol consumption on so-called “pedal pubs” — large, multi-person bicycles equipped with a U-shaped bar, often used for tours or bachelor parties.

“There’s never been such a large increase in availability all at once,” said Sherk, calling Ontario’s expansion “unprecedented.”

False profits

Tim Stockwell, a University of Victoria professor and former director of the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research, says corporate influence helps explain why governments are failing to address alcohol’s health risks.

“Evidence for harms from alcohol has been with us for decades and has only strengthened,” said Stockwell. “Commercial vested interests have always dominated the policy sphere.”

Federal lobbying records show Beer Canada has routinely targeted Health Canada and more than two dozen federal agencies to influence policy on labeling, taxation and public health messaging. This includes closed-door meetings with MPs and senior officials from the Department of Finance and Agriculture Canada.

Beer Canada did not respond to multiple requests for comment by press time. Spirits Canada and Molson Coors Beverage Company also did not respond to multiple requests for comment.

Butt, of the University of Saskatchewan, says the money governments generate from alcohol sales creates a conflict with their public health mandate.

Federal and provincial governments generate revenue from alcohol through a range of mechanisms, including excise taxes, provincial markups, sales taxes and licensing fees. In some provinces, governments also earn profits from government-run liquor stores.

“[Governments] look at it from a lost revenue perspective, rather than from a public health perspective,” said Butt.

Ian Culbert, of Public Health Canada, puts it more bluntly. “Governments have a substance sales issue, as opposed to a substance use issue,” he said. “But it’s short-term gain for long-term pain.”

“Public Health wants to reduce consumption, because all consumption contributes to harm,” said Stockwell, of the Canadian Institute for Substance Use Research. “Commerce wants to … expand the consumption.”

A familiar playbook

Every expert interviewed for this story said the alcohol industry is following the tobacco industry’s playbook.

“They’re using the same sort of rear-guard action policies: denial, heavy government lobbying, government revenue,” said Butt.

“I don’t trust either the industry nor the government to do the right thing based upon past action. I think it’s important that consumers are educated.”

Adam Sherk agrees. “If I was [the industry], I would also be scared about consumers knowing this link [to cancer] better,” he said.

“The strategy is to obfuscate the link — point to studies that might be older or found no link, or put a lot of things in the water so it seems less clear than it is.”

But alcohol, experts say, is harder to regulate than tobacco. “Nobody liked to be in an airplane with smokers eating dinner next to smokers, so it was really easy to demonize smoking,” said Culbert.

“Alcohol is so ingrained in everything: we drink when we’re happy, we drink when we’re sad, we drink when we’re bored — we drink.”

Still, the normalization does not make the risks any less real. “There’s a mortality rate attached to this,” said Butt.

“And that’s the thing that is tragic — this is a modifiable risk factor.”

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Our content is always free – but if you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism, consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

Addictions

Toronto offering free drug kits with pipes, syringes across city

From LifeSiteNews

Toronto’s so-called ‘harm reduction’ program delivers free drug kits, including crack and meth pipes and syringes, via a hotline and reportedly over 100 distribution sites.

The city of Toronto is delivering drug kits across the city via a drug hotline, as part of its “harm reduction” plan.

The city of Toronto is operating a Mobile and Street Outreach program to allow residents to call a hotline and have drug kits, complete with pipes for smoking crack or meth, naloxone, syringes, condoms, delivered to them for free.

“The province of Ontario made it clear that there was no place for ‘safe consumption,’ for the consumption of drugs anywhere near schools and daycare centers,” Canadian commenter Ben Mulroney in a July 22 episode of his show.

“And instead, what we’ve noticed is the rise of the use of drugs and the giving out of all the materials that you need to do drugs in homeless shelters across this city,” Mulroney continued.

Mulroney interviewed a Toronto resident named Amy working with the New Toronto Initiative, who explained how the city’s drugs policies are exacerbating, not solving, the drug crisis.

Amy shared that she collected a free drug kit from the Queen West “harm reduction” center in Toronto. The kit included an OD package, to help someone who is suffering from a drug overdose.

However, it also included pipes for smoking crack or meth, naloxone, syringes, condoms, and instructions on “safer crystal meth smoking,” such as how to use a meth pipe.

According to the City of Toronto, the drug kits were only to be distributed from five supervised consumption treatment centers in Ingleton, Lake Ontario, Victoria Park, and Don Valley Parkway.

However, Amy revealed that there are “over 100 distribution sites in the city of Toronto.”

Additionally, the city’s “Street & Mobile Van Outreach” program delivers “harm reduction supplies” across the city.

“This stuff is supposed to be circumscribed to these five locations,” Mulroney explained, adding that, despite this, “the city has decided that they’re circumventing that by offering mobile delivery.”

The supplies provided by the mobile service include injecting and smoking supplies, which can be delivered within 20 to 40 minutes of calling the hotline.

Furthermore, earlier this year, Toronto began building new homeless shelters, including one in Amy’s neighborhood, which raised concerns regarding community safety.

However, the city assured Amy that the homeless shelter will not be a “safe injection” site. Later, Amy learned that the shelters will be handing out the euphemistic “harm reduction kits,” which include drug supplies.

“And if you are telling us that in homeless shelters it is now open season for people to consume drugs at their leisure, then you are putting people who never had any interaction with drugs right next to people who do,” Mulroney warned.

As LifeSiteNews previously reported, a government funded vending machine is dispensing drug supplies and contraception just meters away from a Toronto school.

The distribution of the kits comes after the Liberal “safe-supply” program was deemed such a disaster in British Columbia that the province asked former Prime Minister Justin Trudeau to recriminalize drugs in public spaces. Nearly two weeks later, the Trudeau government announced it would “immediately” end the province’s drug program.

“Safe supply” is a euphemism for government-provided drugs given to addicts under the assumption that a more controlled batch of narcotics reduces the risk of overdose. Critics of the policy stress that giving addicts drugs only enables their behavior, puts the public at risk, disincentivizes recovery from addiction, and has not reduced – and sometimes has even increased – overdose deaths when implemented.

Beginning in early 2023, Trudeau’s federal policy effectively decriminalized hard drugs on a trial-run basis in British Columbia.

Under the policy, the federal government allowed people within the province to possess up to 2.5 grams of hard drugs without criminal penalty. Selling drugs remained a crime.

Since its implementation, the province’s drug policy has been widely criticized, especially after it was found that the province broke three different drug-related overdose records in the first month the new law was in effect.

The effects of decriminalizing hard drugs in various parts of Canada have been exposed in Aaron Gunn’s recent documentary Canada is Dying and in the U.K. Telegraph journalist Steven Edginton’s mini-documentary Canada’s Woke Nightmare: A Warning to the West.

Addictions

Critics question conclusions of new Ontario “safer supply” study

A new study links safer supply to health improvements, but critics say results are muddied by methadone use and extra supports

A new study that compares safer supply with a traditional approach to addiction treatment has ignited debate among addiction experts.

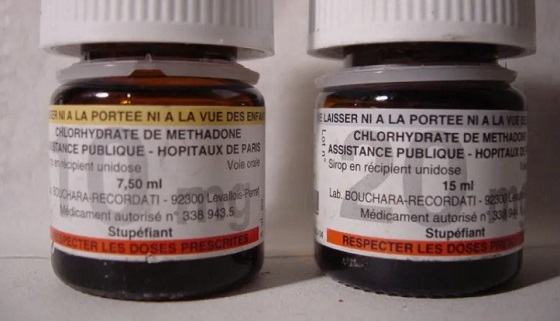

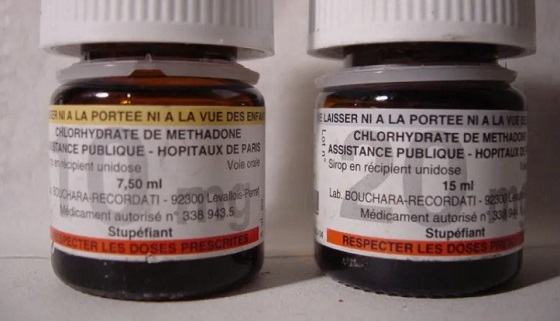

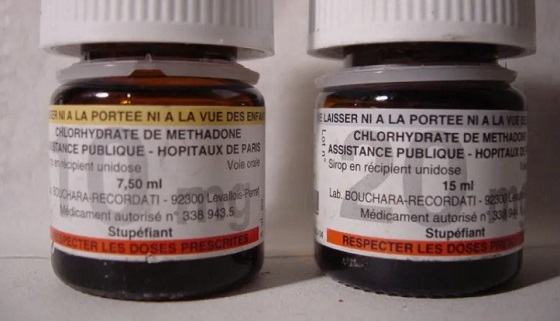

The study, published in The Lancet Public Health in April, examined health outcomes for people receiving safer supply and compared them to a similar group of people receiving methadone, a drug used to reduce drug cravings and withdrawal symptoms.

It concluded that safer supply programs significantly improved participants’ health outcomes. Safer supply provides people at high risk of overdose with prescription opioids as a safer alternative to toxic street drugs.

But critics question the study’s conclusions. They note that many safer supply participants had access to more support services and that the majority also received methadone. These factors make it difficult to identify which treatment drove the positive results.

“The study did not compare [safer supply] to methadone, but rather the initiation of both with several other unaccounted variables,” wrote psychiatrists Dr. Robert Tanguaya and Dr. Nickie Mathew in a formal critique also published in The Lancet.

Findings

The peer-reviewed study is the first in Canada to compare the health outcomes for people receiving safer supply with those receiving methadone through a program known as opioid agonist therapy. Opioid agonist therapy, or OAT, is widely used to treat opioid use disorder.

The study, which was led by teams at Unity Health Toronto, ICES, the University of Toronto and the Ontario Network of People Who Use Drugs, followed about 1,700 Ontarians who started treatment between 2016 and 2021. Half were receiving prescribed hydromorphone through Ontario’s safer supply programs; the other half were receiving methadone through an OAT program.

Participants were tracked for up to one year. Both groups saw improvements, including fewer overdoses, emergency room visits, hospital stays and new infections.

“The findings suggest [safer supply] programs play an important, complementary role to traditional opioid agonist treatment in expanding the options available to support people who use drugs,” the study says.

However, when compared against each other, the safer supply group had higher rates of overdose, ER visits and hospital admissions than those on methadone.

Still, the authors conclude that safer supply can complement methadone, especially for people who do not respond well to traditional options like OAT.

Subscribe for free to get BTN’s latest news and analysis – or donate to our investigative journalism fund.

Confounders

In their May 27 critique in The Lancet Public Health, psychiatrists Tanguay and Mathew say the study fails to isolate the effects of safer supply.

“It is unclear from this study whether the benefits attributed to [safer supply] initiation came from the prescribed … hydromorphone or not,” they wrote.

One concern is that most safer supply participants were also on methadone — a highly dose-dependent medication — and the study did not account for how much of each drug they received.

Dr. Leonara Regenstreif, a primary care physician who specializes in substance use disorders, raised a similar point in an email to Canadian Affairs.

She noted that 84 per cent of safer supply participants in the study were already on methadone when they began receiving hydromorphone.

“It would take a lot of fudging to be able to say [safer supply] was responsible for an outcome, when that group was actually receiving two drugs,” she said.

The main study’s authors did not respond to requests for comment. Instead, they directed Canadian Affairs to their May 27 response to Tanguay and Mathew’s critique, also published in The Lancet.

Wraparound care

Critics also say that improved outcomes among safer supply participants may be due to the extensive additional health care they received while on safer supply.

This additional care was evidenced in study participants’ medication costs.

In the year after treatment began, median medication costs for safer supply patients rose by more than $13,000 per person. By comparison, costs for those on methadone rose by about $1,600.

Glen McGee, a statistics professor at the University of Waterloo, says this suggests safer supply participants may have received broader care, including treatment for other conditions like HIV or hepatitis C.

“This could suggest treatment [of the safer supply group] involved more thorough care in addition to [safer supply], which could also account for some of the improved outcomes,” he said.

In their response to Tanguay and Mathew’s critique, the main study’s authors said the additional care is not a flaw — it reflects how Ontario’s safer supply model is designed.

“Embedding hydromorphone prescriptions within other health and social services that address the complex needs of people at high risk of drug-related harms is a deliberate and defining feature,” they wrote.

McGee suggests the challenge of isolating the impact of broader care makes it difficult to draw broad conclusions about safer supply’s role in patients’ health outcomes.

“The analyses in the main paper seem reasonable, but the conclusions are perhaps too strong,” said McGee. “We don’t necessarily know if [safer supply] alone would be as effective.”

Overdose risk

Critics also focused on safer supply participants having a higher risk of overdose than those in opioid agonist therapy.

Although safer supply patients were more likely to stay in treatment than methadone patients, overdose rates remained higher for safer supply patients — even after adjusting for people who dropped out from the methadone group.

The study authors say this is likely because safer supply patients started at higher risk and many continued using street drugs early in treatment.

“The smaller decline among [safer supply] recipients might reflect higher baseline risk and greater ongoing exposure to the unregulated drug supply early in treatment,” they wrote.

They also noted that very few people died in either group, showing that treatment — whether safer supply or methadone — offers protection.

However, Regenstreif urges caution.

“If you peel away the stats language, underneath it all you have a cohort with higher risks of opioid toxicity and other hazards of ongoing drug use,” said Regenstreif.

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Our content is always free – but if you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism, consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

-

COVID-192 days ago

COVID-192 days agoTamara Lich says Carney government wants her jailed for 7 years

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCompetition Bureau recommends bureaucratic power grab over airline industry

-

Business16 hours ago

Business16 hours agoBank of Canada Study Confirms Collapse in Consumer Confidence Amid Trade War Fallout

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoMcTeague: Will Carney actually build a pipeline?

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCarney setting the stage for massive deficits this year and beyond

-

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days ago

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days agoWhy Are Woke White Folks More Offended By Controversial Sports Names?

-

Business16 hours ago

Business16 hours agoIn search for savings, Carney government should shrink—not just cap—the federal bureaucracy

-

Addictions14 hours ago

Addictions14 hours agoCritics question conclusions of new Ontario “safer supply” study