Fraser Institute

Canada can solve its productivity ‘emergency’—we just need politicians on board

From the Fraser Institute

By Jake Fuss

Policymakers are slowly acknowledging the problem, but their proposed solutions are troubling.

According to Carolyn Rogers, senior deputy governor of the Bank of Canada, it’s time to “break the glass” and respond to Canada’s productivity “emergency.” Unfortunately, the country is unlikely to solve this issue any time soon as politicians are doubling down on the policy status quo rather than making sorely needed reforms.

Worker productivity—the level of output in the economy per hour worked—is a crucial indicator of a country’s underlying economic performance. When productivity increases, we not only increase our output and efficiency, but worker wages typically rise as well.

According to Statistics Canada, the country’s productivity dropped for six consecutive quarters before eking out a small gain in the final quarter of 2023. Rogers is right, this is an emergency, and it’s unsurprising that living standards for Canadians are falling alongside our productivity. Since the second quarter of 2022 (when it peaked post-COVID), inflation-adjusted per-person GDP (a common indicator of living standards) declined from $60,178 to $58,111 by the end of 2023—and declined during five of those six quarters, now sitting below where it was at the end of 2014.

Policymakers are slowly acknowledging the problem, but their proposed solutions are troubling. Federal Finance Minister Chrystia Freeland, for instance, recently emphasized the importance of making “investments in productivity and growth.” Yet, the federal government increased taxes on capital gains in its recent budget, which will disincentivize investment in Canada. Usually, when a politician says the word “investment” this is a fancy way of saying we need more government spending.

And in fact, more government spending appears to be the popular solution to every problem for most governments in Canada these days. Canadian premiers and the prime minister already support this approach in health care even though it’s been tried for decades. The result? In 2023, the longest wait times for health care on record despite having the most expensive system (as a share of GDP) among high-income universal health-care countries.

And now, these same policymakers are advocating for the same approach to boost productivity—that is, throw taxpayer money at the problem and hope it will somehow go away.

But there’s hope—governments have other options. For starters, governments from coast to coast could eliminate interprovincial trade barriers, which limit productivity improvements by (among other things) shielding inefficient local businesses from competition from businesses in other provinces. Governments also effectively prohibit the entry of foreign-owned competitors in crucial industries such as telecommunications and air travel. There’s less incentive for Canadian firms to innovate or improve when there’s no threat to shake things up.

Moreover, if governments reduced regulatory red tape and subsequent compliance costs, firms could allocate more resources towards training their workers, investing in equipment, and producing new and better products. And if governments reduced tax rates on families and businesses, they could make Canada more attractive to productive businesses, high-skilled workers and investors. Our current relatively high tax rates on capital gains, personal income and businesses income discourage capital investment and scare away the best and brightest scientists, engineers, doctors and entrepreneurs.

The Trudeau government, and other governments in Canada, seemingly want to spend their way out of our productivity emergency. While some level of government spending can help improve productivity, continued spending increases reallocate resources from the private sector to the government sector, which is by nature less productive. Governments should impose credible restraints (i.e. fiscal rules) on the growth of government spending to prevent this crowding out of private-sector investment.

There are plenty of ways Canada can boost productivity. We just need policymakers to be on board.

Author:

Business

Latest shakedown attempt by Canada Post underscores need for privatization

From the Fraser Institute

By Alex Whalen and Jake Fuss

For the second time in just six months, the Canadian Union of Postal Workers (CUPW) is threatening strike action. As Canadians know all too well, postal strikes can be highly disruptive given the federal government provides Canada Post with a near-monopoly on letter mail across the country. CUPW is well aware of this and uses it to their advantage in negotiations. While CUPW has the right to ask for whatever they like, Canadians should finally be freed from this albatross.

In January, the Trudeau government loaned Canada Post a whopping $1.034 billion to help “maintain its solvency and continue operating.” Since 2018, Canada Post has lost more than $4.6 billion, and according to its latest financial update, lost more than $100 million in the first quarter of 2025 alone. Canadians are on the hook for these losses because the federal government owns Canada Post.

Salaries and other employee costs comprise more than 66 per cent of Canada Post’s expenses, and CUPW and Canada Post management both know they can simply pass any losses on to Canadians. Consequently, there’s less incentive for management to control the bottom line or make reasonable budget requests when negotiating with the government. But if the government privatizes Canada Post, it would impose a proper constraint on costs that doesn’t currently exist. This is only fair given there’s no compelling reason why Canadians should underwrite the inflation of salaries in a money-losing Crown corporation.

Of course, government ownership of Canada Post is archaic. When the organization was founded more than 250 years ago, the world was quite different. In today’s age of Amazon, a plethora of delivery services exist coast-to-coast that serve Canadian consumers. Other countries including the Netherlands, Austria and Germany long ago privatized their postal services. The result was increased competition, which in turn reduced prices and improved quality.

Alongside privatization, the federal government should also eliminate Canada Post’s near-monopoly status on letter mail. This policy is purportedly meant to ensure universal service. But in reality, it prohibits other potential service providers from entering the letter-delivery market (including in remote areas that may experience less Canada Post service post-privatization), deprives Canadians of choice, and crucially, reduces the incentive for Canada Post to improve its service.

Simply put, the federal government should focus on its core responsibilities, and delivering mail is clearly not one of them. Given Canada Post’s latest attempted shakedown of Canadians, it’s never been clearer that it’s time for Canada Post to go the way of Air Canada, de Havilland and CN Rail. Once upon a time, the federal government owned all three of these entities until it became clear there was no reason for the government to own an airline, build planes or deliver goods by train. Why is letter mail any different? Canadians deserve better.

Business

Massive government child-care plan wreaking havoc across Ontario

From the Fraser Institute

By Matthew Lau

It’s now more than four years since the federal Liberal government pledged $30 billion in spending over five years for $10-per-day national child care, and more than three years since Ontario’s Progressive Conservative government signed a $13.2 billion deal with the federal government to deliver this child-care plan.

Not surprisingly, with massive government funding came massive government control. While demand for child care has increased due to the government subsidies and lower out-of-pocket costs for parents, the plan significantly restricts how child-care centres operate (including what items participating centres may purchase), and crucially, caps the proportion of government funds available to private for-profit providers.

What have families and taxpayers got for this enormous government effort? Widespread child-care shortages across Ontario.

For example, according to the City of Ottawa, the number of children (aged 0 to 5 years) on child-care waitlists has ballooned by more than 300 per cent since 2019, there are significant disparities in affordable child-care access “with nearly half of neighbourhoods underserved, and limited access in suburban and rural areas,” and families face “significantly higher” costs for before-and-after-school care for school-age children.

In addition, Ottawa families find the system “complex and difficult to navigate” and “fewer child care options exist for children with special needs.” And while 42 per cent of surveyed parents need flexible child care (weekends, evenings, part-time care), only one per cent of child-care centres offer these flexible options. These are clearly not encouraging statistics, and show that a government-knows-best approach does not properly anticipate the diverse needs of diverse families.

Moreover, according to the Peel Region’s 2025 pre-budget submission to the federal government (essentially, a list of asks and recommendations), it “has maximized its for-profit allocation, leaving 1,460 for-profit spaces on a waitlist.” In other words, families can’t access $10-per-day child care—the central promise of the plan—because the government has capped the number of for-profit centres.

Similarly, according to Halton Region’s pre-budget submission to the provincial government, “no additional families can be supported with affordable child care” because, under current provincial rules, government funding can only be used to reduce child-care fees for families already in the program.

And according to a March 2025 Oxford County report, the municipality is experiencing a shortage of child-care staff and access challenges for low-income families and children with special needs. The report includes a grim bureaucratic predication that “provincial expansion targets do not reflect anticipated child care demand.”

Child-care access is also a problem provincewide. In Stratford, which has a population of roughly 33,000, the municipal government reports that more than 1,000 children are on a child-care waitlist. Similarly in Port Colborne (population 20,000), the city’s chief administrative officer told city council in April 2025 there were almost 500 children on daycare waitlists at the beginning of the school term. As of the end of last year, Guelph and Wellington County reportedly had a total of 2,569 full-day child-care spaces for children up to age four, versus a waitlist of 4,559 children—in other words, nearly two times as many children on a waitlist compared to the number of child-care spaces.

More examples. In Prince Edward County, population around 26,000, there are more than 400 children waitlisted for licensed daycare. In Kawartha Lakes and Haliburton County, the child-care waitlist is about 1,500 children long and the average wait time is four years. And in St. Mary’s, there are more than 600 children waitlisted for child care, but in recent years town staff have only been able to move 25 to 30 children off the wait list annually.

The numbers speak for themselves. Massive government spending and control over child care has created havoc for Ontario families and made child-care access worse. This cannot be a surprise. Quebec’s child-care system has been largely government controlled for decades, with poor results. Why would Ontario be any different? And how long will Premier Ford allow this debacle to continue before he asks the new prime minister to rethink the child-care policy of his predecessor?

-

Crime2 days ago

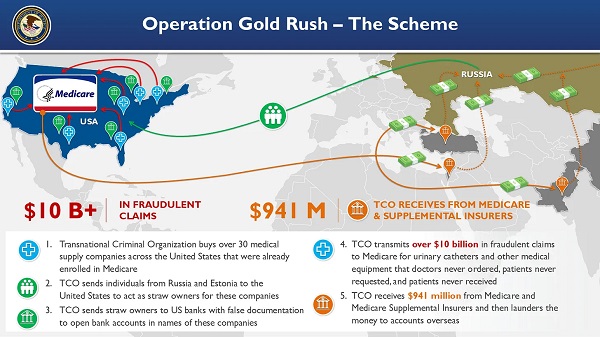

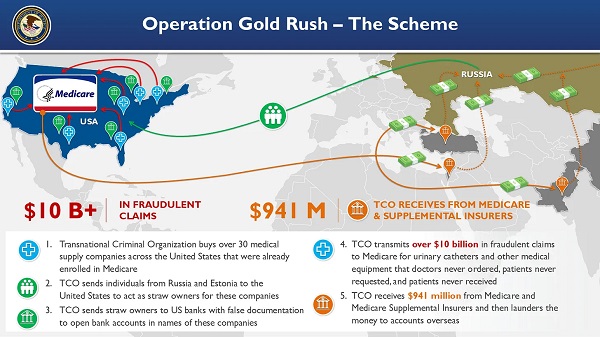

Crime2 days agoNational Health Care Fraud Takedown Results in 324 Defendants Charged in Connection with Over $14.6 Billion in Alleged Fraud

-

Health2 days ago

Health2 days agoRFK Jr. Unloads Disturbing Vaccine Secrets on Tucker—And Surprises Everyone on Trump

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoElon Musk slams Trump’s ‘Big Beautiful Bill,’ calls for new political party

-

International22 hours ago

International22 hours agoCBS settles with Trump over doctored 60 Minutes Harris interview

-

Business14 hours ago

Business14 hours agoLatest shakedown attempt by Canada Post underscores need for privatization

-

Business14 hours ago

Business14 hours agoWhy it’s time to repeal the oil tanker ban on B.C.’s north coast

-

Censorship Industrial Complex1 day ago

Censorship Industrial Complex1 day agoGlobal media alliance colluded with foreign nations to crush free speech in America: House report

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoRFK Jr. says Hep B vaccine is linked to 1,135% higher autism rate