Fraser Institute

Aboriginal rights now more constitutionally powerful than any Charter right

From the Fraser Institute

By Bruce Pardy

A judge of the British Columbia Supreme Court recently found that the Cowichan First Nation holds Aboriginal title over 800 acres of government land in Richmond, British Columbia. Wherever Aboriginal title is found to exist, said the court, it’s a “prior and senior right” to fee simple title, whether public or private. That means it trumps the property that Canadians hold in their houses, farms and factories.

In Canada, property rights do not have constitutional status. No right to property is included in the Charter of Rights and Freedoms. Fee simple title is merely a gloss on the state’s constitutional authority to tax, regulate and expropriate private property as it sees fit. But Aboriginal rights are different. They have become more constitutionally powerful than any Charter right.

In 1968, then-Justice Minister Pierre Trudeau released a consultation paper that proposed a constitutional charter of human rights. It was the first iteration of what would become the Charter. In the paper, Trudeau proposed to guarantee a right to property. So did drafts that followed. But some provincial governments were dead set against entrenching property rights. By 1980, property had been dropped from proposals. The final version of the Charter, adopted in 1982, does not mention it. Canada’s Constitution does not protect property rights.

Except for Aboriginal property. Trudeau’s 1968 paper made no mention of Aboriginal rights, nor did drafts leading up to the 1980 proposal. Aboriginal groups and their supporters launched a campaign to have Aboriginal rights recognized. They succeeded just in time. Section 35, essentially an afterthought, recognized and affirmed the “existing aboriginal and treaty rights of the aboriginal peoples of Canada.” That section was put into the Constitution but not as part of the Charter. That might sound like section 35 is weaker than a Charter right, but it’s the opposite.

Section 35 affirms Aboriginal rights that existed as of 1982. But since 1982, the Supreme Court of Canada has used section 35 to champion, enlarge and reimagine Aboriginal rights. The Court has “discovered” rights never recognized in the law before 1982. In 1997, it articulated a new vision of Aboriginal title. In 2004, it established the Crown’s “duty to consult.” In 2014, it recognized Aboriginal title over a tract of Crown land. In 2021, it gave Aboriginal rights under section 35 to an American Indigenous group.

Now the B.C. court in the Cowichan decision has said that Aboriginal title takes precedence over private property. Last November, a judge of the New Brunswick King’s Bench suggested similarly. Where a claim of Aboriginal title succeeds over land held in fee simple, she said, the court may instruct the government to expropriate the private property and hand it over to the Aboriginal group.

Governments and legislatures have shown little inclination to turn back these developments. But even if they wanted to, the Constitution stands in the way.

Section 33 of the Charter, the “Notwithstanding clause” (NWC), allows provincial legislatures and the federal Parliament to enact legislation notwithstanding the Charter rights guaranteed in sections 2 and 7 to 15. That means that they can pass statutes that might infringe these Charter rights. Use of the NWC clause prevents courts from striking down the statute as unconstitutional. The main part of the NWC reads:

33. (1) Parliament or the legislature of a province may expressly declare in an Act of Parliament or of the legislature, as the case may be, that the Act or a provision thereof shall operate notwithstanding a provision included in section 2 or sections 7 to 15 of this Charter.

Section 35 is not part of the Charter. It is not subject to the NWC. Legislatures cannot ignore it, legislate around it, or change its meaning. Barring a constitutional amendment, courts have exclusive domain over the scope and application of section 35. In the constitutional hierarchy, Aboriginal rights rest above the “fundamental freedoms” and rights of the Charter.

Lest there was any doubt about that status, section 25 of the Charter spells it out. Charter rights and freedoms, the section says, “shall not be construed so as to abrogate or derogate from any aboriginal, treaty or other rights or freedoms that pertain to the aboriginal peoples of Canada.”

That does not mean that Aboriginal rights are absolute. Legislation or government action may sometimes infringe Aboriginal rights. But courts, not legislatures, control when, where, and under what circumstances that can happen. The Supreme Court of Canada has established the process and criteria by which governments must justify infringements of section 35 to the courts’ satisfaction.

Section 35, like much of the rest of the Constitution, is subject to an onerous amending formula. It cannot be easily changed or repealed.

Alberta

ChatGPT may explain why gap between report card grades and standardized test scores is getting bigger

From the Fraser Institute

By Paige MacPherson and Max Shang

In Alberta, the gap between report card grades and test/exam scores increased sharply in 2022—the same year ChatGPT came out.

Report card grades and standardized test scores should rise and fall together, since they measure the same group of students on the same subjects. But in Alberta high schools, report card grades are rising while scores on Provincial Achievement Tests (PAT) and diploma exams are not.

Which raises the obvious question—why?

Report card grades partly reflect student performance in take-home assignments. Standardized tests and diploma exams, however, quiz students on their knowledge and skills in a supervised environment. In Alberta, the gap between report card grades and test/exam scores increased sharply in 2022—the same year ChatGPT came out. And polling shows Canadian students now rely heavily on ChatGPT (and other AI platforms).

Here’s what the data show.

In Alberta, between 2016 and 2019 (the latest year of available comparable data), the average standardized test score covering math, science, social study, biology, chemistry, physics, English and French language arts was just 64, while the report card grade 73.3—or 14.5 per cent higher. Data for 2020 and 2021 are unavailable due to COVID-19 school closures, but between 2022 and 2024, the gap widened to 20 per cent. This trend holds regardless of school type, course or whether the student was male or female. Across the board, since 2022, students in Alberta high schools are performing significantly better in report card grades than on standardized tests.

Which takes us back to AI. According to a recent KPMG poll, 73 per cent of students in Canada (high school, vocational school, college and university) said they use generative AI in their schoolwork, an increase from the previous year. And 71 per cent say their grades improved after using generative AI.

If AI is simply used to aid student research, that’s one thing. But more than two-thirds (66 per cent) of those using generative AI said that although their grades increased, they don’t think they’re learning or retaining as much knowledge. Another 48 per cent say their “critical thinking” skills have deteriorated since they started using AI.

Acquiring knowledge is the foundation of higher-order thinking and critical analysis. We’re doing students a deep disservice if we don’t ensure they expand their knowledge while in school. And if teachers award grades, which are essentially inflated by AI usage at home, they set students up for failure. It’s the academic equivalent of a ski coach looking at a beginner and saying, “You’re ready for the black diamond run.” That coach would be fired. Awarding AI-inflated grades is not fair to students who will later struggle in college, the workplace or life beyond school.

Finally, the increasing popularity of AI underscores the importance of standardized testing and diploma exams. And parents knew this even before the AI wave. A 2022 Leger poll found 95 per cent of Canadian parents with kids in K-12 schools believe it’s important to know their child’s academic performance in the core subjects by a fair and objective measure. Further, 84 per cent of parents support standardized testing, specifically, to understand how their children are doing in reading, writing and mathematics. Alberta is one of the only provinces to administer standardized testing and diploma exams every year.

Clearly, parents should oppose any attempt to reduce accountability and objective testing in Alberta schools.

Business

Carney government needs stronger ‘fiscal anchors’ and greater accountability

From the Fraser Institute

By Tegan Hill and Grady Munro

Following the recent release of the Carney government’s first budget, Fitch Ratings (one of the big three global credit rating agencies) issued a warning that the “persistent fiscal expansion” outlined in the budget—characterized by high levels of spending, borrowing and debt accumulation—will erode the health of Canada’s finances and could lead to a downgrade in Canada’s credit rating.

Here’s why this matters. Canada’s credit rating impacts the federal government’s cost of borrowing money. If the government’s rating gets downgraded—meaning Canadian federal debt is viewed as an increasingly risky investment due to fiscal mismanagement—it will likely become more expensive for the government to borrow money, which ultimately costs taxpayers.

The cost of borrowing (i.e. the interest paid on government debt) is a significant part of the overall budget. This year, the federal government will spend a projected $55.6 billion on debt interest, which is more than one in every 10 dollars of federal revenue, and more than the government will spend on health-care transfers to the provinces. By 2029/30, interest costs will rise to a projected $76.1 billion or more than one in every eight dollars of revenue. That’s taxpayer money unavailable for programs and services.

Again, if Canada’s credit rating gets downgraded, these costs will grow even larger.

To maintain a good credit rating, the government must prevent the deterioration of its finances. To do this, governments establish and follow “fiscal anchors,” which are fiscal guardrails meant to guide decisions regarding spending, taxes and borrowing.

Effective fiscal anchors ensure governments manage their finances so the debt burden remains sustainable for future generations. Anchors should be easily understood and broadly applied so that government cannot get creative with its accounting to only technically abide by the rule, but still give the government the flexibility to respond to changing circumstances. For example, a commonly-used rule by many countries (including Canada in the past) is a ceiling/target for debt as a share of the economy.

The Carney government’s budget establishes two new fiscal anchors: balancing the federal operating budget (which includes spending on day-to-day operations such as government employee compensation) by 2028/29, and maintaining a declining deficit-to-GDP ratio over the years to come, which means gradually reducing the size of the deficit relative to the economy. Unfortunately, these anchors will fail to keep federal finances from deteriorating.

For instance, the government’s plan to balance the “operating budget” is an example of creative accounting that won’t stop the government from borrowing money each year. Simply put, the government plans to split spending into two categories: “operating spending” and “capital investment” —which includes any spending or tax expenditures (e.g. credits and deductions) that relates to the production of an asset (e.g. machinery and equipment)—and will only balance operating spending against revenues. As a result, when the government balances its operating budget in 2028/29, it will still incur a projected deficit of $57.9 billion when spending on capital is included.

Similarly, the government’s plan to reduce the size of the annual deficit relative to the economy each year does little to prevent debt accumulation. This year’s deficit is expected to equal 2.5 per cent of the overall economy—which, since 2000, is the largest deficit (as a share of the economy) outside of those run during the 2008/09 financial crisis and the pandemic. By measuring its progress off of this inflated baseline, the government will technically abide by its anchor even as it runs relatively large deficits each and every year.

Moreover, according to the budget, total federal debt will grow faster than the economy, rising from a projected 73.9 per cent of GDP in 2025/26 to 79.0 per cent by 2029/30, reaching a staggering $2.9 trillion that year. Simply put, even the government’s own fiscal plan shows that its fiscal anchors are unable to prevent an unsustainable rise in government debt. And that’s assuming the government can even stick to these anchors—which, according to a new report by the Parliamentary Budget Officer, is highly unlikely.

Unfortunately, a federal government that can’t stick to its own fiscal anchors is nothing new. The Trudeau government made a habit of abandoning its fiscal anchors whenever the going got tough. Indeed, Fitch Ratings highlighted this poor track record as yet another reason to expect federal finances to continue deteriorating, and why a credit downgrade may be on the horizon. Again, should that happen, Canadian taxpayers will pay the price.

Much is riding on the Carney government’s ability to restore Canada’s credibility as a responsible fiscal manager. To do this, it must implement stronger fiscal rules than those presented in the budget, and remain accountable to those rules even when it’s challenging.

-

Health1 day ago

Health1 day agoLack of adequate health care pushing Canadians toward assisted suicide

-

National19 hours ago

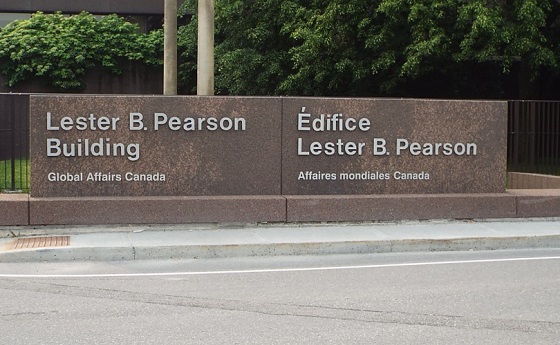

National19 hours agoWatchdog Demands Answers as MP Chris d’Entremont Crosses Floor

-

Alberta19 hours ago

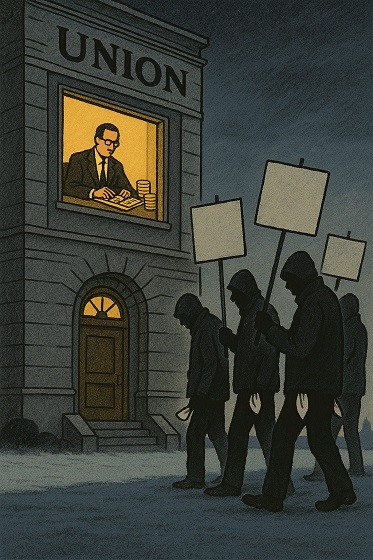

Alberta19 hours agoATA Collect $72 Million in Dues But Couldn’t Pay Striking Teachers a Dime

-

Artificial Intelligence19 hours ago

Artificial Intelligence19 hours agoAI seems fairly impressed by Pierre Poilievre’s ability to communicate

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoIt should not take a crisis for Canada to develop the resources that make people and communities thrive.

-

Dr John Campbell2 days ago

Dr John Campbell2 days agoCures for Cancer? A new study shows incredible results from cheap generic drug Fenbendazole

-

Artificial Intelligence1 day ago

Artificial Intelligence1 day agoAI Faces Energy Problem With Only One Solution, Oil and Gas

-

Media18 hours ago

Media18 hours agoBreaking News: the public actually expects journalists to determine the truth of statements they report