Health

World Health Organization negotiating to take control “when the next event with pandemic potential strikes”

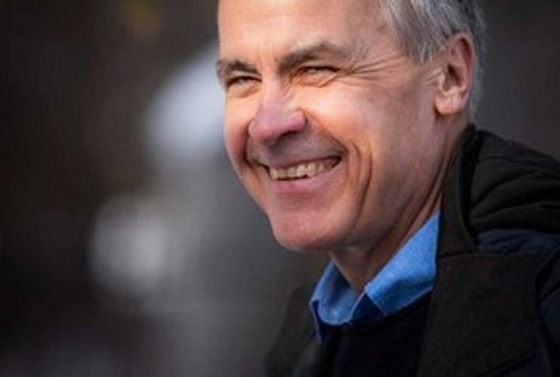

From Dr. John Campbell on Youtube

British Health Researcher Dr. John Campbell is raising the alarm about the latest moves by the World Health Organization to consolidate authority over governments all around the world.

As argued in UK Parliament, the World Health Organization is asking for a vast transfer of power and some MP’s are very much in favour of ceding power to the WHO.

In this video, Dr. Campbell outlines new regulations countries are currently negotiating to hand over vast new responsibilities to the WHO. The treaties would put the World Health Organization in charge – not just of the global health response, but of what information is shared, and how that information is shared. The regulations would also allow the WHO to take control not just in the event of a health emergency, but in the event of any emergency that could potentially impact public health.

From the commentary notes of Dr. John Campbell.

Countries from around the world are currently working on negotiating and/or amending two international instruments, which will help the world be better prepared when the next event with pandemic potential strikes.

The Intergovernmental Negotiating Body (INB) https://inb.who.int to draft and negotiate a convention, agreement or other international instrument to strengthen pandemic prevention, preparedness and response (commonly known as the Pandemic Accord).

Amendments to the International Health Regulations https://www.who.int/teams/ihr/working…) https://apps.who.int/gb/wgihr/pdf_fil… to amend the current International Health Regulations (2005) https://apps.who.int/gb/wgihr/ https://www.who.int/publications/i/it… 66 2005 articles

Underlined and bold = proposal to add text

Strikethrough = proposal to delete existing text (cut and paste does not copy strike through so I’ve put them in comic sans)

Article 1 Definitions

“standing recommendation” means non-binding advice issued by WHO

“temporary recommendation” means non-binding advice issued by WHO

Article 2 Scope and purpose including through health systems

readiness and resilience in ways that are commensurate with and restricted to public health risk – all risks – with a potential to impact public health,

Article 3 Principles

The implementation of these Regulations shall be with full respect for the dignity, human rights and fundamental freedoms of persons

Article 4 Responsible authorities

each State Party should inform WHO about the establishment of its National Competent Authority responsible for overall implementation of the IHR that will be recognized and held accountable

Article 5 Surveillance

the State Party may request a further extension not exceeding two years from the Director-General,

who shall make the decision refer the issue to World Health Assembly which will then take a decision on the same

WHO shall collect information regarding events through its surveillance activities

Article 6 Notification

No sharing of genetic sequence data or information shall be required under these Regulations.

Article 9: Other Reports

reports from sources other than notifications or consultations

Before taking any action based on such reports, WHO shall consult with and attempt to obtain verification from the State Party in whose territory the event is allegedly occurring

Article 10 Verification

whilst encouraging the State Party to accept the offer of collaboration by WHO, taking into account the views of the State Party concerned.

Article 11 Exchange of information

WHO shall facilitate the exchange of information between States Parties and ensure that the Event Information Site For National IHR Focal Points offers a secure and reliable platform

Parties referred to in those provisions, shall not make this information generally available to other States Parties, until such time as when: (e) WHO determines it is necessary that such information be made available to other States Parties to make informed, timely risk assessments.

Fraser Institute

Long waits for health care hit Canadians in their pocketbooks

From the Fraser Institute

Canadians continue to endure long wait times for health care. And while waiting for care can obviously be detrimental to your health and wellbeing, it can also hurt your pocketbook.

In 2024, the latest year of available data, the median wait—from referral by a family doctor to treatment by a specialist—was 30 weeks (including 15 weeks waiting for treatment after seeing a specialist). And last year, an estimated 1.5 million Canadians were waiting for care.

It’s no wonder Canadians are frustrated with the current state of health care.

Again, long waits for care adversely impact patients in many different ways including physical pain, psychological distress and worsened treatment outcomes as lengthy waits can make the treatment of some problems more difficult. There’s also a less-talked about consequence—the impact of health-care waits on the ability of patients to participate in day-to-day life, work and earn a living.

According to a recent study published by the Fraser Institute, wait times for non-emergency surgery cost Canadian patients $5.2 billion in lost wages in 2024. That’s about $3,300 for each of the 1.5 million patients waiting for care. Crucially, this estimate only considers time at work. After also accounting for free time outside of work, the cost increases to $15.9 billion or more than $10,200 per person.

Of course, some advocates of the health-care status quo argue that long waits for care remain a necessary trade-off to ensure all Canadians receive universal health-care coverage. But the experience of many high-income countries with universal health care shows the opposite.

Despite Canada ranking among the highest spenders (4th of 31 countries) on health care (as a percentage of its economy) among other developed countries with universal health care, we consistently rank among the bottom for the number of doctors, hospital beds, MRIs and CT scanners. Canada also has one of the worst records on access to timely health care.

So what do these other countries do differently than Canada? In short, they embrace the private sector as a partner in providing universal care.

Australia, for instance, spends less on health care (again, as a percentage of its economy) than Canada, yet the percentage of patients in Australia (33.1 per cent) who report waiting more than two months for non-emergency surgery was much higher in Canada (58.3 per cent). Unlike in Canada, Australian patients can choose to receive non-emergency surgery in either a private or public hospital. In 2021/22, 58.6 per cent of non-emergency surgeries in Australia were performed in private hospitals.

But we don’t need to look abroad for evidence that the private sector can help reduce wait times by delivering publicly-funded care. From 2010 to 2014, the Saskatchewan government, among other policies, contracted out publicly-funded surgeries to private clinics and lowered the province’s median wait time from one of the longest in the country (26.5 weeks in 2010) to one of the shortest (14.2 weeks in 2014). The initiative also reduced the average cost of procedures by 26 per cent.

Canadians are waiting longer than ever for health care, and the economic costs of these waits have never been higher. Until policymakers have the courage to enact genuine reform, based in part on more successful universal health-care systems, this status quo will continue to cost Canadian patients.

Health

Just 3 Days Left to Win the Dream Home of a Lifetime!

|

|

|

|

|