Addictions

Why is B.C.’s safer supply program shrinking?

By Alexandra Keeler

Experts say physicians have lost their ‘zeal’ for prescribing safer supply amid growing concerns about diversion and effectiveness

Participation in B.C.’s safer supply program — which offers prescription opioids to people who use drugs — has dropped by nearly 25 per cent over the past two years, according to recent government data.

The B.C. Ministry of Health says updated prescribing guidelines and tighter program oversight are behind the decline.

But addiction experts say the story is more complicated.

“Many of my addiction medicine colleagues have stopped prescribing ‘safe supply’ hydromorphone to their patients because of the high rates of diversion … and lack of efficacy in stabilizing the substance use disorder (sometimes worsening it),” said Dr. Launette Rieb, a clinical associate professor at the University of British Columbia and addiction medicine specialist.

“Many doctors who initially supported ‘safe supply’ no longer provide it but do not wish to talk about it publicly for fear of reprisals,” she said in her email.

Missing data

B.C. has had safer supply programs in place province-wide since 2021.

Participation in its program peaked at nearly 5,200 individuals in March 2023, and then declined to fewer than 3,900 individuals by December 2024. This is the most recent data publicly available, according to B.C.’s health ministry.

In an emailed statement, the ministry attributed the decline to updated clinical guidance and more restrictive prescribing practices “aimed at strengthening the integrity and safety of the program.”

In February, the province updated its safer supply prescribing guidelines to require most patients of the program to consume prescription opioids under the supervision of health-care professionals — a practice known as “witnessed dosing.”

The B.C. government has not released any data on how many patients have been transitioned to witnessed dosing.

The ministry did not address Canadian Affairs’ questions about whether patients are being cut off involuntarily from the program, whether fewer physicians are prescribing or whether barriers to accessing safer supply have increased.

‘Dependence, tolerance, addiction’

Some experts say the decline in safer supply participation is due to physicians being influenced by their peers and public controversy over the program.

Dr. Karen Urbanoski, an associate professor in the Public Health and Social Policy department at the University of Victoria, says peer influence plays a significant role in prescribing practices.

A 2024 study found the uptake of prescribed safer supply in B.C. was closely tied to prescribers’ professional networks.

“These peer influences are apparent for both the uptake of [safer supply] prescribing and its discontinuation — they are likely playing a role here,” Urbanoski said in an email to Canadian Affairs.

Urbanoski also points to the broader environment — including negative media coverage and uncertainty about program funding — as factors behind the decline.

“Media discourse and general politicization of [safer supply] has likely had a ‘cooling effect’ on prescribing,” she said.

Dr. Leonara Regenstreif, a primary care physician and founding member of Addiction Medicine Canada, says many physicians embraced safer supply without fully grasping its clinical risks. Addiction Medicine Canada is an advocacy group representing 23 addiction specialists across Canada.

Regenstreif says physicians too young to have practiced during the peak of OxyContin prescribing were often enthusiastic prescribers of safer supply in the program’s early days. OxyContin is a prescription opioid that helped spark North America’s addiction crisis.

“In my experience, the MD colleagues who have embraced [safer supply] prescribing most zealously … never experienced the trap of writing scripts without knowing what was ahead — dependence, tolerance, addiction, consequences,” her emailed statement says.

Now, many of these physicians are looking for an “exit ramp,” Regenstreif says, as concerns over safer supply diversion and its treatment benefits grow.

Reib, of the UBC, says some of her colleagues in addictions medicine fear speaking out about their concerns with the program.

“Some of my colleagues have had their lives threatened by their patients who have become financially dependent on selling their [hydromorphone],” said Rieb.

The College of Physicians and Surgeons of B.C., which represents physicians in the province, referred Canadian Affairs’ questions about declining program participation to the health ministry and the BC Centre on Substance Use. The centre was unable to provide comment by press time.

Public backlash

The decline in B.C.’s safer supply participation unfolds amid mounting scrutiny of the program and its effectiveness.

Rieb says that the program’s framing — as free, safe and widely available — may run counter to longstanding public health strategies aimed at reducing drug use through pricing and harm awareness.

“Drivers of public use of substances are availability, cost, and perception of harm,” she said. “[Safe supply] is being promoted as safe, free and available for the asking.”

There have been reports of youth gaining access to diverted safer supply opioids and developing addictions to fentanyl as a result. Last September, B.C. father Gregory Sword testified before the House of Commons that his teenage daughter died after accessing diverted safer supply opioids.

B.C.’s recent decision to overhaul its prescribing guidelines followed revelations of a widespread scam by dozens of B.C. pharmacists to exploit the safer supply program to maximize profits.

Experts also note that Canada still lacks the evidence needed to assess the long-term health outcomes of people in safer supply programs. There is currently no research in Canada tracking these long-term health outcomes.

“There is a lack of research to date on retention on [safer supply],” said Urbanoksi.

Rieb agrees. “There are many methodological problems with the recent studies that conclude [the] benefit of pharmaceutical alternatives (‘safe supply’),” she said.

“We need long term studies that look at risks/harms as well as potential benefits.”

Regenstreif says the recent drop in participation may have an unintended upside — encouraging more people with substance use disorders to try what she sees as a more effective treatment: opioid agonist therapy, or OAT. This therapy uses medications like methadone or buprenorphine to reduce withdrawal symptoms and cravings.

“If fewer people are accessing [safer supply] tablets … more people with [opioid use disorder] might accept proper OAT treatment,” she said.

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Addictions

The Shaky Science Behind Harm Reduction and Pediatric Gender Medicine

By Adam Zivo

Both are shaped by radical LGBTQ activism and questionable evidence.

Over the past decade, North America embraced two disastrous public health movements: pediatric gender medicine and “harm reduction” for drug use. Though seemingly unrelated, these movements are actually ideological siblings. Both were profoundly shaped by extremist LGBTQ activism, and both have produced grievous harms by prioritizing ideology over high-quality scientific evidence.

While harm reductionists are known today for championing interventions that supposedly minimize the negative effects of drug consumption, their movement has always been connected to radical “queer” activism. This alliance began during the 1980s AIDS crisis, when some LGBTQ activists, hoping to reduce HIV infections, partnered with addicts and drug-reform advocates to run underground needle exchanges.

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

In the early 2000s, after the North American AIDS epidemic was brought under control, many HIV organizations maintained their relevance (and funding) by pivoting to addiction issues. Despite having no background in addiction medicine, their experience with drug users in the context of infectious diseases helped them position themselves as domain experts.

These organizations tended to conceptualize addiction as an incurable infection—akin to AIDS or Hepatitis C—and as a permanent disability. They were heavily staffed by progressives who, influenced by radical theory, saw addicts as a persecuted minority group. According to them, drug use itself was not the real problem—only society’s “moralizing” norms.

These factors drove many HIV organizations to lobby aggressively for harm reduction at the expense of recovery-oriented care. Their efforts proved highly successful in Canada, where I am based, as HIV researchers were a driving force behind the implementation of supervised consumption sites and “safer supply” (free, government-supplied recreational drugs for addicts).

From the 2010s onward, the association between harm reductionism and queer radicalism only strengthened, thanks to the popularization of “intersectional” social justice activism that emphasized overlapping forms of societal oppression. Progressive advocates demanded that “marginalized” groups, including drug addicts and the LGBTQ community, show enthusiastic solidarity with one another.

These two activist camps sometimes worked on the same issues. For example, the gay community is struggling with a silent epidemic of “chemsex” (a dangerous combination of drugs and anonymous sex), which harm reductionists and queer theorists collaboratively whitewash as a “life-affirming cultural practice” that fosters “belonging.”

For the most part, though, the alliance has been characterized by shared tones and tactics—and bad epistemology. Both groups deploy politicized, low-quality research produced by ideologically driven activist-researchers. The “evidence-base” for pediatric gender medicine, for example, consists of a large number of methodologically weak studies. These often use small, non-representative samples to justify specious claims about positive outcomes. Similarly, harm reduction researchers regularly conduct semi-structured interviews with small groups of drug users. Ignoring obvious limitations, they treat this testimony as objective evidence that pro-drug policies work or are desirable.

Gender clinicians and harm reductionists are also averse to politically inconvenient data. Gender clinicians have failed to track long-term patient outcomes for medically transitioned children. In some cases, they have shunned detransitioners and excluded them from their research. Harm reductionists have conspicuously ignored the input of former addicts, who generally oppose laissez-faire drug policies, and of non-addict community members who live near harm-reduction sites.

Both fields have inflated the benefits of their interventions while concealing grievous harms. Many vulnerable children, whose gender dysphoria otherwise might have resolved naturally, were chemically castrated and given unnecessary surgeries. In parallel, supervised consumption sites and “safer supply” entrenched addiction, normalized public drug use, flooded communities with opioids, and worsened public disorder—all without saving lives.

In both domains, some experts warned about poor research practices and unmeasured harms but were silenced by activists and ideologically captured institutions. In 2015, one of Canada’s leading sexologists, Kenneth Zucker, was fired from the gender clinic he had led for decades because he opposed automatically affirming young trans-identifying patients. Analogously, dozens of Canadian health-care professionals have told me that they feared publicly criticizing aspects of the harm-reduction movement. They thought doing so could invite activist harassment while jeopardizing their jobs and grants.

By bullying critics into silence, radical activists manufactured false consensus around their projects. The harm reductionists insist, against the evidence, that safer supply saves lives. Their idea of “evidence-based policymaking” amounts to giving addicts whatever they ask for. “The science is settled!” shout the supporters of pediatric gender medicine, though several systematic reviews proved it was not.

Both movements have faced a backlash in recent years. Jurisdictions throughout the world are, thankfully, curtailing irreversible medical procedures for gender-confused youth and shifting toward a psychotherapy-based “wait and see” approach. Drug decriminalization and safer supply are mostly dead in North America and have been increasingly disavowed by once-supportive political leaders.

Harm reductionists and queer activists are trying to salvage their broken experiments, occasionally by drawing explicit parallels between their twin movements. A 2025 paper published in the International Journal of Drug Policy, for example, asserts that “efforts to control, repress, and punish drug use and queer and trans existence are rising as right-wing extremism becomes increasingly mainstream.” As such, there is an urgent need to “cultivate shared solidarity and action . . . whether by attending protests, contacting elected officials, or vocally defending these groups in hostile spaces.”

How should critics respond? They should agree with their opponents that these two radical movements are linked—and emphasize that this is, in fact, a bad thing. Large swathes of the public understand that chemically and surgically altering vulnerable children is harmful, and that addicts shouldn’t be allowed to commandeer public spaces. Helping more people grasp why these phenomena arose concurrently could help consolidate public support for reform and facilitate a return to more restrained policies.

Adam Zivo is director of the Canadian Centre for Responsible Drug Policy.

For the full experience, please upgrade your subscription and support a public interest startup.

We break international stories and this requires elite expertise, time and legal costs.

Addictions

BC premier admits decriminalizing drugs was ‘not the right policy’

From LifeSiteNews

Premier David Eby acknowledged that British Columbia’s liberal policy on hard drugs ‘became was a permissive structure that … resulted in really unhappy consequences.’

The Premier of Canada’s most drug-permissive province admitted that allowing the decriminalization of hard drugs in British Columbia via a federal pilot program was a mistake.

Speaking at a luncheon organized by the Urban Development Institute last week in Vancouver, British Columbia, Premier David Eby said, “I was wrong … it was not the right policy.”

Eby said that allowing hard drug users not to be fined for possession was “not the right policy.

“What it became was a permissive structure that … resulted in really unhappy consequences,” he noted, as captured by Western Standard’s Jarryd Jäger.

LifeSiteNews reported that the British Columbia government decided to stop a so-called “safe supply” free drug program in light of a report revealing many of the hard drugs distributed via pharmacies were resold on the black market.

Last year, the Liberal government was forced to end a three-year drug decriminalizing experiment, the brainchild of former Prime Minister Justin Trudeau’s government, in British Columbia that allowed people to have small amounts of cocaine and other hard drugs. However, public complaints about social disorder went through the roof during the experiment.

This is not the first time that Eby has admitted he was wrong.

Trudeau’s loose drug initiatives were deemed such a disaster in British Columbia that Eby’s government asked Trudeau to re-criminalize narcotic use in public spaces, a request that was granted.

Records show that the Liberal government has spent approximately $820 million from 2017 to 2022 on its Canadian Drugs and Substances Strategy. However, even Canada’s own Department of Health in a 2023 report admitted that the Liberals’ drug program only had “minimal” results.

Official figures show that overdoses went up during the decriminalization trial, with 3,313 deaths over 15 months, compared with 2,843 in the same time frame before drugs were temporarily legalized.

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoSagrada Familia Basilica in Barcelona is now tallest church in the world

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoGondek’s exit as mayor marks a turning point for Calgary

-

Agriculture2 days ago

Agriculture2 days agoCloned foods are coming to a grocer near you

-

Censorship Industrial Complex19 hours ago

Censorship Industrial Complex19 hours agoSenate Grills Meta and Google Over Biden Administration’s Role in COVID-Era Content Censorship

-

Fraser Institute2 days ago

Fraser Institute2 days agoOttawa continues to infringe in areas of provincial jurisdiction

-

Business20 hours ago

Business20 hours agoYou Won’t Believe What Canada’s Embassy in Brazil Has Been Up To

-

Business18 hours ago

Business18 hours agoMystery cloaks Doug Ford’s funding of media through Ontario advertising subsidy

-

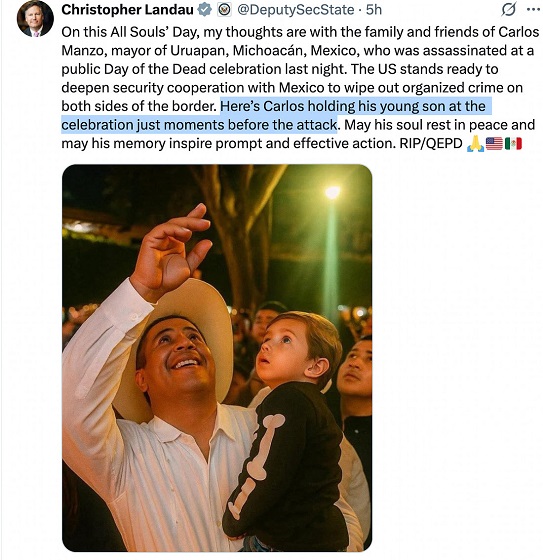

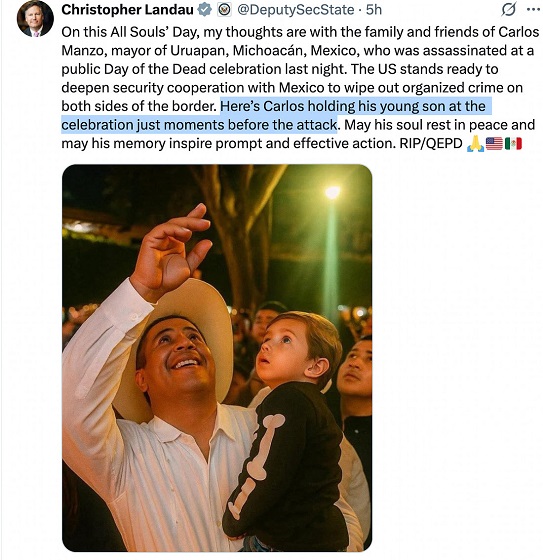

Crime6 hours ago

Crime6 hours agoPublic Execution of Anti-Cartel Mayor in Michoacán Prompts U.S. Offer to Intervene Against Cartels