Economy

When Potatoes Become a Luxury: Canada’s Grocery Gouging Can’t Continue

By Jeremy Nuttall

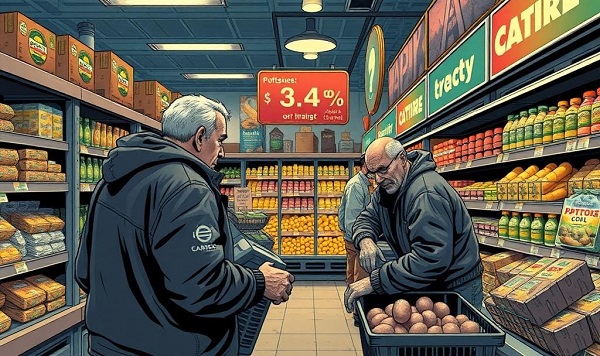

I don’t want to live in a country where pensioners have to put back potatoes, a food that supported millions of lives in desperate times

It was a routine wait in the grocery line last year when I personally witnessed the true cost of the grocery price spike. An elderly lady in front of me in the lineup did a double take when the clerk told her the total for her bill.

“What’s $10?” she asked, looking at the cashier’s screen. The clerk told her it was the handful of potatoes she’d grabbed. The woman, easily old enough to be retired, put the potatoes back.

Being middle-aged with a decent full-time job, until that moment, I was fortunate enough that experiencing the rising cost of groceries was not much more than a bit of a drag. But seeing a pensioner putting potatoes back highlighted the problem. The humble tuber has sustained whole civilizations in dire circumstances due to its being inexpensive and nourishing. Now it’s a luxury item?

After two years of complaints about the cost of groceries, the government pretending to fix the issue with the grocery code of conduct (and a lot of big talk), and more Canadians hitting food banks than at any time in recent memory, earlier this month we found out food prices will rise again next year.

The Food Price Report, produced by a joint effort between several Canadian universities, predicted a five per cent increase for meat and vegetables in 2025. That’s more than double the predicted rate of inflation from BMO for the coming 12 months.

Yet again, Canadian government actions have proven worthless.

The message is clear, and “we can’t really help you” is pretty much that message.

Another idea the government had to solve this was to head down to the U.S. to beg some of their chains to open up in Canada. This, rather than breaking up the big Canadian-owned grocery chains dominated by a couple of corporate giants already caught in a major price-fixing scandal, was their best idea.

Anything to get out of doing the work and angering the people with whom they hit the cocktail circuit.

I stopped buying my produce, and most of my meat, at large outlets a couple of years ago. I knew I was saving money, but just how much surprised me recently. I was at a Safeway and wanted to buy a russet potato there to save myself making another stop. I saw the price was $2.69 a pound. The spud I chose was more than a pound—potentially a $3 potato. Disgusted, I left the store without a thing to mash, bake, or julienne.

A few days later, I headed to my usual produce market, the Triple A market on Hastings in Burnaby, a trusty institution with a lot of character. I purchased a big russet potato, a big red onion, two Roma tomatoes, and two Ambrosia apples. (These are random items; please don’t try to make a pie out of this.)

My total was $5.15. This seemed reasonable to me. Right after, I went back to the same Safeway. I purchased the same items, while trying my best to get the weight as close as possible to the first batch I bought.

The result? Even with the Triple A red onion and potato having a couple hundred grams more weight, the Safeway total for the same basket was $8.83. That’s forty per cent more, probably closer to 50 per cent if you factor in the size difference for the onion and potato from Triple A.

A quick look around my nearest Jim Pattison-owned Buy-Low (or Buy Low Sell High, as we call it around my house) revealed prices similar to Safeway, yet the neighbourhood Sungiven, a Vancouver Asian market chain, had prices closer to those of the produce stand.

Now, the argument is often that big grocers have more overhead, advertising budgets, and larger staff. But I think it’s fair to say there’s something suspicious going on here. One thing is clear, though: big grocers are increasingly strictly for suckers.

Out here in B.C., this predicted five per cent increase in grocery prices will have companions by way of increases to property taxes recently passed in Metro Vancouver and a 17 per cent increase to natural gas rates in the province.

We may have a tariff war on the horizon, making all that even worse.

This crushing of Canadians can’t go on. Sadly, it will, due in part to the complete lack of real action from the authorities meant to protect the public interest.

To be clear, I’m not an expert on grocery stores or farming. I’m sure there are flaws in my complaints.

But one thing I know for certain is I don’t want to live in a country where pensioners have to put back potatoes—a food that has saved millions of lives during destitute times—at the checkout after seeing how much they cost.

And any government agency or elected official who thinks it can half-ass the response to something like that while collecting a paycheque is gouging Canadians in their own way.

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Economy

What the Data Shows About the New Canada-Alberta Pipeline Opportunity

From Energy Now

By Canada Powered by Women

Canada has entered a new period of energy cooperation, marking one of the biggest shifts in federal–provincial alignment on energy priorities in years.

Last week as Prime Minister Mark Carney and Alberta Premier Danielle Smith signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) that outlines how both governments will approach a potential pipeline to British Columbia’s coast.

The agreement, which has been described as a “new starting point” after years of tension, lays the groundwork for a privately financed pipeline while also linking this commitment to a broader set of infrastructure priorities across oil and gas, LNG, renewables, critical minerals and electricity transmission.

It also sets out how a privately financed project, moving roughly 300,000 to 400,000 barrels of oil to global markets each day, will be reviewed.

Now that the announcement is behind us, attention has turned to how (or if) a pipeline is going to get built.

Alberta has set out its ambitions, British Columbia has its conditions, and the federal government has its own expectations. Together, these positions are shaping what some are calling a “grand bargain” which will be made up of trade-offs.

Trade-offs are not a new concept for the engaged women that Canada Powered by Women (CPW) represents, as they’ve been showing up in our research for several years now. And anyone who reads us also knows we like to look at what the data says.

According to new polling from the Angus Reid Institute, a clear majority of Canadians support a pipeline, with national backing above 60 per cent. And there’s strong support for the pipeline among those in B.C. This aligns with other emerging data points that show Canadians are looking for practical solutions that strengthen affordability and long-term reliability.

By the numbers:

• 60 per cent of Canadians support the pipeline concept, while 25 per cent oppose it.

• 53 per cent of people support in British Columbia, compared to 37 percent opposed.

• 74 per cent of people in Alberta and Saskatchewan support the pipeline.

Our research shows the same trends.

A large majority (85 per cent) of engaged women agree that building pipelines and refining capacity within the country should be prioritized. They favour policies that will progress stability, affordability and long-term economic opportunity.

A key feature of the MOU is the expectation of Indigenous ownership and benefit sharing, which Alberta and B.C. governments identify as essential, and which aligns with public opinion. As of right now, Indigenous groups remain split on support for a pipeline.

The agreement also signals that changes to the federal Oil Tanker Moratorium Act may need to be considered. The moratorium, in place since 2019, is designed to limit large tanker traffic on the North Coast of B.C. because of navigation risks in narrow channels and the need to protect sensitive coastal ecosystems.

Those in favour of the pipeline point to this as a critical barrier to moving Canadian oil to international markets.

Polling from the Angus Reid Institute shows that 47 per cent of Canadians believe the moratorium could be modified or repealed if stronger safety measures are in place. Again, we come back to trade-offs.

The MOU is a starting point and does not replace consultation, environmental review or provincial alignment. These steps are still required before any project can advance. Taken together, the agreement and the data show broad support for strengthening Canada’s energy options.

This will be an issue that engaged women are no doubt going to watch, and the conversation is likely to move from ideas to discussing what trade-offs can be made to bring this opportunity to life.

Business

US Energy Secretary says price of energy determined by politicians and policies

From the Daily Caller News Foundation

During the latest marathon cabinet meeting on Dec. 2, Energy Secretary Chris Wright made news when he told President Donald Trump that “The biggest determinant of the price of energy is politicians, political leaders, and polices — that’s what drives energy prices.”

He’s right about that, and it is why the back-and-forth struggle over federal energy and climate policy plays such a key role in America’s economy and society. Just 10 months into this second Trump presidency, the administration’s policies are already having a profound impact, both at home and abroad.

While the rapid expansion of AI datacenters over the past year is currently being blamed by many for driving up electric costs, power bills were skyrocketing long before that big tech boom began, driven in large part by the policies of the Obama and Biden administration designed to regulate and subsidize an energy transition into reality. As I’ve pointed out here in the past, driving up the costs of all forms of energy to encourage conservation is a central objective of the climate alarm-driven transition, and that part of the green agenda has been highly effective.

Dear Readers:

As a nonprofit, we are dependent on the generosity of our readers.

Please consider making a small donation of any amount here.

Thank you!

President Trump, Wright, and other key appointees like Interior Secretary Doug Burgum and EPA Administrator Lee Zeldin have moved aggressively throughout 2025 to repeal much of that onerous regulatory agenda. The GOP congressional majorities succeeded in phasing out Biden’s costly green energy subsidies as part of the One Big Beautiful Bill Act, which Trump signed into law on July 4. As the federal regulatory structure eases and subsidy costs diminish, it is reasonable to expect a gradual easing of electricity and other energy prices.

This year’s fading out of public fear over climate change and its attendant fright narrative spells bad news for the climate alarm movement. The resulting cracks in the green facade have manifested rapidly in recent weeks.

Climate-focused conflict groups that rely on public fears to drive donations have fallen on hard times. According to a report in the New York Times, the Sierra Club has lost 60 percent of the membership it reported in 2019 and the group’s management team has fallen into infighting over elements of the group’s agenda. Greenpeace is struggling just to stay afloat after losing a huge court judgment for defaming pipeline company Energy Transfer during its efforts to stop the building of the Dakota Access Pipeline.

350.org, an advocacy group founded by Bill McKibben, shut down its U.S. operations in November amid funding woes that had forced planned 25 percent budget cuts for 2025 and 2026. Employees at EDF voted to form their own union after the group went through several rounds of budget cuts and layoffs in recent months.

The fading of climate fears in turn caused the ESG management and investing fad to also fall out of favor, leading to a flood of companies backtracking on green investments and climate commitments. The Net Zero Banking Alliance disbanded after most of America’s big banks – Goldman Sachs, J.P. Morgan Chase, Citigroup, Wells Fargo and others – chose to drop out of its membership.

The EV industry is also struggling. As the Trump White House moves to repeal Biden-era auto mileage requirements, Ford Motor Company is preparing to shut down production of its vaunted F-150 Lightning electric pickup, and Stellantis cancelled plans to roll out a full-size EV truck of its own. Overall EV sales in the U.S. collapsed in October and November following the repeal of the $7,500 per car IRA subsidy effective Sept 30.

The administration’s policy actions have already ended any new leasing for costly and unneeded offshore wind projects in federal waters and have forced the suspension or abandonment of several projects that were already moving ahead. Capital has continued to flow into the solar industry, but even that industry’s ability to expand seems likely to fade once the federal subsidies are fully repealed at the end of 2027.

Truly, public policy matters where energy is concerned. It drives corporate strategies, capital investments, resource development and movement, and ultimately influences the cost of energy in all its forms and products. The speed at which Trump and his key appointees have driven this principle home since Jan. 20 has been truly stunning.

David Blackmon is an energy writer and consultant based in Texas. He spent 40 years in the oil and gas business, where he specialized in public policy and communications.

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCarney’s Toronto cabinet meetings cost $530,000

-

Artificial Intelligence2 days ago

Artificial Intelligence2 days agoAI is accelerating the porn crisis as kids create, consume explicit deepfake images of classmates

-

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days ago

Bruce Dowbiggin2 days agoIntegration Or Indignation: Whose Strategy Worked Best Against Trump?

-

Health2 days ago

Health2 days ago23,000+ Canadians died waiting for health care in one year as Liberals pushed euthanasia

-

MAiD2 days ago

MAiD2 days ago101-year-old woman chooses assisted suicide — press treats her death as a social good

-

Health2 days ago

Health2 days agoNews RFK Jr.’s vaccine committee to vote on ending Hepatitis B shot recommendation for newborns

-

COVID-1922 hours ago

COVID-1922 hours agoCanadian legislator introduces bill to establish ‘Freedom Convoy Recognition Day’ as a holiday

-

espionage2 days ago

espionage2 days agoDigital messages reportedly allege Chinese police targeted dissident who died suspiciously near Vancouver