Health

Was football player Terrance Howard really dead? His parents didn’t think so.

From LifeSiteNews

The Uniform Determination of Death Act (UDDA) states that there must be an irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain for a declaration of brain death. The way doctors currently diagnose brain death does not comply with the law under the UDDA.

North Carolina Central University football player Terrance Howard died recently after a car accident reportedly left him “brain dead.” But his family disputed this diagnosis and requested that their son be transferred to another facility for treatment of his brain injury, leading to conflict with Terrance’s doctors and hospital. According to News One, his parents claimed that Atrium Health Carolinas Medical Center wanted to kill their son for his organs, and accused doctors of snickering and laughing while refusing to help him. His father, Anthony Allen, told News One that the hospital removed Terrance from life support against his family’s wishes and forcibly ejected his family from his room. The family posted videos on social media of apparent police officers entering Terrance’s hospital room, and said that the hospital threatened them with criminal action for trespassing.

If these allegations are true, the Howard family has every right to be outraged at the disrespectful treatment they received at Atrium Health. Especially now, as the legitimacy of brain death is coming under increasing scrutiny, it is outrageous that hospitals and doctors continue being so heavy-handed. The National Catholic Bioethics Center (NCBC), formerly a staunch supporter of “brain death,” released a statement in April 2024, saying:

Events in the last several months have revealed a decisive breakdown in a shared understanding of brain death (death by neurological criteria) which has been critical in shaping the ethical practice of organ transplantation. At stake now is whether clinicians, potential organ donors, and society can agree on what it means to be dead before vital organs are procured.

The NCBC statement was prompted by the newest brain death guideline which explicitly allows people with partial brain function to be declared brain dead. But the Uniform Determination of Death Act (UDDA) states that there must be an irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain for a declaration of brain death. The way doctors currently diagnose brain death does not comply with the law under the UDDA.

Terrance Howard’s story is reminiscent of the mistreatment of another Black teenager, Jahi McMath. In 2013, Jahi was a quiet, cautious teenager with sleep apnea who underwent a tonsillectomy and palate reconstruction to improve her airflow while sleeping. An hour after the surgery, she started spitting up blood. Her parents requested repeatedly to see a doctor without success. Her mother, Nailah Winkfield, said, “No one was listening to us, and I can’t prove it, but I really feel in my heart: if Jahi was a little white girl, I feel we would have gotten a little more help and attention.”

Jahi continued to bleed until she had a cardiac arrest just after midnight. She was pulseless for ten minutes during her “code blue” resuscitation. Two days later, her electroencephalogram (EEG) was flatline, and it was clear that Jahi had suffered a severe brain injury which was worsening. But rather than treating these findings aggressively, her doctors proceeded toward a diagnosis of brain death. Three days after her surgery, her parents were informed that their daughter was “dead” and that Jahi could now become an organ donor. The family was stunned. How could Jahi be dead? She was warm, she was moving occasionally, and her heart was still beating. As a Christian, Nailah believed her daughter’s spirit remained in her body as long as her heart continued to beat. While the family sought medical and legal assistance, Children’s Hospital Oakland doubled down, refusing to feed Jahi for three weeks. The hospital finally agreed to release Jahi to the county coroner for a death certificate, following which her family would be responsible for her.

On January 3, 2014, Jahi received a death certificate from California, listing her cause of death as “Pending Investigation.” Why was the hospital so adamant about insisting Jahi was dead, even to the point of issuing a death certificate? Possibly because California’s Medical Injury Compensation Reform Act limits noneconomic damages to $250,000. If Jahi was “dead,” the hospital and its malpractice insurer would only be liable for $250,000. But if Jahi was alive, there would be no limit to the amount her family could claim for her ongoing care.

After Jahi was transferred to New Jersey, the only US state with a religious exemption to a diagnosis of brain death, she began to improve. After noticing that Jahi’s heart rate would decrease at the sound of her mother’s voice, the family began asking her to respond to commands, and videoed her correct responses. Jahi went through puberty and began to menstruate — something not seen in corpses! By August 2014 she was stable enough to move into her mother’s apartment for continuing care. Subsequently Jahi was examined by two neurologists (Dr. Calixto Machado and Dr. D. Alan Shewmon) who found that she had definitely improved: she no longer met the criteria for brain death and was in a minimally conscious state. Jahi continued responding to her family in a meaningful way until her death in June 2018 from complications of liver failure.

How could Jahi McMath, who was declared brain dead by three doctors, who failed three apnea tests, and who had four flatline EEGs and a radioisotope scan showing no intracranial blood flow, go on to recover neurologic function? Very likely, due to a condition called Global Ischemic Penumbra, or GIP. Like every other organ, the brain shuts down its function when its blood flow is reduced in order to conserve energy. At 70 percent of normal blood flow, the brain’s neurological functioning is reduced, and at a 50 percent reduction the EEG becomes flatline. But tissue damage doesn’t begin until blood flow to the brain drops below 20 percent of normal for several hours. GIP is a term doctors use to refer to that interval when the brain’s blood flow is between 20 and 50 percent of normal. During GIP the brain will not respond to neurological testing and has no electrical activity on EEG, but still has enough blood flow to maintain tissue viability — meaning that recovery is still possible. During GIP, a person will appear “brain dead” using the current medical guidelines and testing, but with continuing care they could potentially improve.

Dr. D. Alan Shewmon, one of the world’s leading authorities on brain death, describes GIP this way:

This [GIP] is not a hypothesis but a mathematical necessity. The clinically relevant question is therefore not whether GIP occurs but how long it might last. If, in some patients, it could last more than a few hours, then it would be a supreme mimicker of brain death by bedside clinical examination, yet the non-function (or at least some of it) would be in principle reversible.

Dr. Cicero Coimbra first described GIP in 1999, but in the never-ending quest for transplantable organs, his work has been largely ignored. There is absolutely no medical or moral certainty in a brain death diagnosis, and people need to be made aware of this. “Brain dead” people are very ill, and their prognosis may be death, but they deserve to be treated aggressively until they either recover or succumb to natural death. Unfortunately, as the family of Terrance Howard seems to have experienced, doctors are continuing to use a brain death guideline that ignores the reality of GIP and does not comply with brain death law under the UDDA.

Heidi Klessig MD is a retired anesthesiologist and pain management specialist who writes and speaks on the ethics of organ harvesting and transplantation. She is the author of “The Brain Death Fallacy” and her work may be found at respectforhumanlife.com.

Health

All 12 Vaccinated vs. Unvaccinated Studies Found the Same Thing: Unvaccinated Children Are Far Healthier

I joined Del Bigtree in studio on The HighWire to discuss what the data now make unavoidable: the CDC’s 81-dose hyper-vaccination schedule is driving the modern epidemics of chronic disease and autism.

This was not a philosophical debate or a clash of opinions. We walked through irrefutable, peer-reviewed evidence showing that whenever vaccinated and unvaccinated children are compared directly, the unvaccinated group is far healthier—every single time.

Reanalyzing the Largest Vaccinated vs. Unvaccinated Birth-Cohort Study Ever Conducted

At the center of our discussion was our peer-reviewed reanalysis of the Henry Ford Health System vaccinated vs. unvaccinated birth-cohort study (Lamerato et al.)—the largest and most rigorous comparison of its kind ever conducted.

|

The original authors relied heavily on Cox proportional hazards models, a time-adjusted approach that can soften absolute disease burden. Even so, nearly all chronic disease outcomes were higher in vaccinated children.

Our reanalysis used direct proportional comparisons, stripping away the smoothing and revealing the full magnitude of the signal.

- All 22 chronic disease categories favored the unvaccinated cohort when proportional disease burden was examined

- Cancer incidence was 54% higher in vaccinated children (0.0102 vs. 0.0066)

- When autism-associated conditions were grouped appropriately—including autism, ADHD, developmental delay, learning disability, speech disorder, neurologic impairment, seizures, and related diagnoses—the vaccinated cohort showed a 549% higher odds of autism-spectrum–associated clinical outcomes

The findings are internally consistent, biologically coherent, and concordant with every prior vaccinated vs. unvaccinated study, all of which show drastically poorer health outcomes among vaccinated children

The 12 Vaccinated vs. Unvaccinated Studies Regulators Ignore

In the McCullough Foundation Autism Report, we compiled all 12 vaccinated vs. unvaccinated pediatric studies currently available. These studies span different populations, countries, study designs, and data sources.

Every single one reports the same overall pattern. Across all 12 studies, unvaccinated children consistently exhibit substantially lower rates of chronic disease, including:

- Autism and other neurodevelopmental disorders

- ADHD, tics, learning and speech disorders

- Asthma, allergies, eczema, and autoimmune conditions

- Chronic ear infections, skin disorders, and gastrointestinal illness

This level of consistency across independent datasets is precisely what epidemiology looks for when assessing causality. It also explains why no federal agency has ever conducted—or endorsed—a fully vaccinated vs. fully unvaccinated safety study.

Flu Shot Failure

We also addressed the persistent failure of seasonal influenza vaccination.

A large Cleveland Clinic cohort study of 53,402 employees followed participants during the 2024–2025 respiratory viral season and found:

- 82.1% of employees were vaccinated against influenza

- Vaccinated individuals had a 27% higher adjusted risk of influenza compared with the unvaccinated state (HR 1.27; 95% CI 1.07–1.51; p = 0.007)

- This corresponded to a negative vaccine effectiveness of −26.9% (95% CI −55.0 to −6.6%), meaning vaccination was associated with increased—not reduced—risk of influenza

When vaccination exposure increases, chronic disease, neurodevelopmental disorders, and inflammatory illness increase with it. When children are unvaccinated, they are measurably healthier across virtually every outcome that matters.

The science needed to confront the chronic disease and autism epidemics already exists. What remains is the willingness to acknowledge it.

Epidemiologist and Foundation Administrator, McCullough Foundation

Support our mission: mcculloughfnd.org

Please consider following both the McCullough Foundation and my personal account on X (formerly Twitter) for further content.

FOCAL POINTS (Courageous Discourse) is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Daily Caller

Ex-FDA Commissioners Against Higher Vaccine Standards Took $6 Million From COVID Vaccine Makers

From the Daily Caller News Foundation

By Emily Kopp

The FDA old guard criticized the new leadership in a Dec. 3 New England Journal of Medicine (NEJM) letter over a higher regulatory bar for vaccines, namely the expectation that most new vaccine approvals will require randomized clinical trials, arguing it could hamper the market.

“Insisting on long, expensive outcomes studies for every updated formulation would delay the arrival of better-matched vaccines when new outbreaks emerge or when additional groups of patients could benefit,” the former commissioners wrote. “Abandoning the existing methods won’t ‘elevate vaccine science’ … It will subject vaccines to a substantially higher and more subjective approval bar.”

But while the former commissioners disclosed their conflicts of interest to the medical journal — per standard practice in scientific publishing — reporters didn’t relay them to the broader public in reports in the Washington Post, STAT News and CNN.

The headlines about a bipartisan rebuke from former occupants of FDA’s highest office give the impression that the Trump administration is contravening established science, but closer inspection reveals a revolving door between pharmaceutical corporations and the agencies overseeing them.

Three of the signatories have received payments totaling $6 million from manufacturers or former manufacturers of COVID vaccines.

Scott Gottlieb has received $2.1 million in cash and stock from his position on the Pfizer board of directors, where he has advised on ethics and regulatory compliance since 2019, according to company filings to the Securities and Exchange Commission. Stephen Ostroff has received $752,310 from Pfizer in consulting fees since 2020, according to OpenPayments.

Mark McClellan has received $3.3 million from Johnson & Johnson as a member of the board of directors since 2013, SEC filings also show. McClellan also consults for the new pharmaceutical arm of the alternative investment management company Blackstone, which invested $750 million in Moderna in April 2025.

Gottlieb and McClellan did not respond to requests for comment. Ostroff could not be reached for comment.

FDA Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research Director Vinay Prasad outlined the higher standards and shared the results of an internal analysis validating 10 reports of children’s deaths following the COVID-19 vaccine in a Nov. 28 memo to staff. He called for introspection and reform at the agency.

The NEJM letter criticizes Prasad for cracking down on a practice called “immunobridging” that infers vaccine efficacy from laboratory tests rather than assessing it through real-world reductions in disease or death. The FDA under the Biden administration expanded COVID vaccines to children using this “immunobridging” technique, extrapolating vaccine efficacy from adults to children based on antibody levels.

Norman Sharpless — who in addition to previously serving as acting FDA commissioner also served as the head of the National Institutes of Health’s National Cancer Institute — consults for Tempus, a company that collaborates with COVID vaccine maker BioNTech. He has helped steer $70 million in investments in biotech through a venture capital firm he founded in November 2024. Sharpless also disclosed $26,180 in payments in 2024 from Chugai Pharmaceutical, a Japanese pharmaceutical company that markets mRNA technology among other drugs, on OpenPayments.

“I was grateful for the opportunity to serve as NCI Director and Acting FDA Commissioner in the first Trump Administration, and strongly support many of the things President Trump is trying to do in the current Administration,” Sharpless said in an email.

Margaret Hamburg, another former FDA commissioner and signatory of the NEJM letter, has since 2020 earned $2.8 million as a member of the board of Alnylam Pharmaceuticals, which markets RNA interference (RNAi) technology.

Hamburg did not respond to a message on LinkedIn.

Most signatories disclosed income from biotech companies testing experimental cancer treatments. These products could face tighter scrutiny under Prasad, a hematologist-oncologist long wary of rubberstamping pricey oncology drugs — which Prasad points out often cause some toxicity — without plausible evidence of an improvement in quality of life or survival.

The former FDA commissioners disclosed ties to Sermonix Pharmaceuticals Inc.; OncoNano Medicine; incyclix; Nucleus Radiopharma; and N-Power, a contractor that runs oncology clinical trials.

Andrew von Eschenbach, who like Sharpless formerly served both as FDA commissioner and the head of the National Cancer Institute, disclosed stock in HistoSonics, a company with investments from Bezos Expeditions and Thiel Bio seeking FDA approval for ultrasound technology targeted at tumors.

Some FDA commissioners who signed onto the letter opposing changes to vaccine approvals have ties to biotechnology investment firms, namely McClellan, who consults Arsenal Capital; Janet Woodcock, who consults RA Capital Management; and Robert Califf, who owns stock in Population Health Partners.

Califf did not respond to an email requesting comment. Woodcock did not respond to requests for comment sent to two medical research advocacy groups with Woodcock on the board. Eschenbach did not respond to a LinkedIn message.

The two signatories without pharmaceutical ties may find their judgement challenged by the FDA investigation into COVID-19 vaccine deaths, having either implemented or formally defended the Biden administration’s headlong expansion of vaccines and boosters to healthy adults and children.

David Kessler executed Biden’s vaccination policy as chief science officer at the Department of Health and Human Services, helping to secure deals for shots with Pfizer and Moderna.

Meanwhile Jane Henney chaired a National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine report published in October 2025 that praised the performance of FDA and Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) vaccine surveillance during the pandemic — underwritten with CDC funding.

That assessment clashes with that of a Senate report, citing internal documents from FDA, finding that CDC never updated its vaccine surveillance tool “V-Safe” to include cardiac symptoms, despite naming myocarditis as a potential adverse event by October 2020, and that top officials in the Biden administration delayed warning pediatricians and other providers about the risk of myocarditis after their approval in some children in May 2021, months after Israeli health officials first detected it in February 2021. The Senate investigation named Woodcock, a signatory of the NEJM letter, as one of the FDA officials who slow-walked the warning.

-

Crime2 days ago

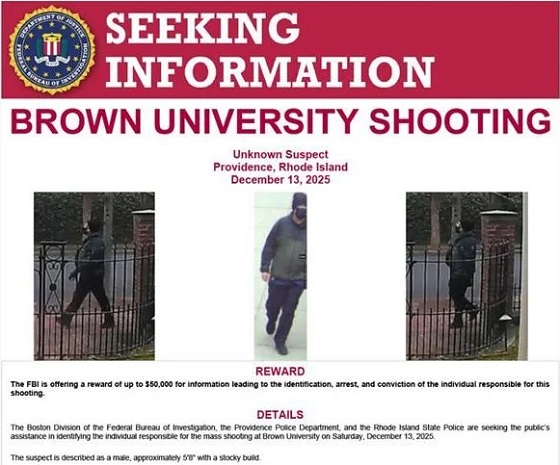

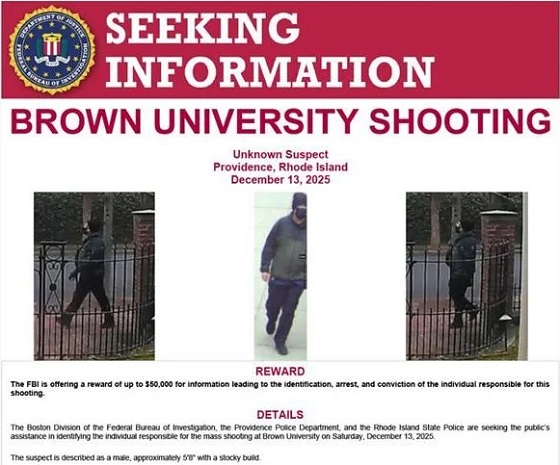

Crime2 days agoBrown University shooter dead of apparent self-inflicted gunshot wound

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoAlberta’s new diagnostic policy appears to meet standard for Canada Health Act compliance

-

Health1 day ago

Health1 day agoRFK Jr reversing Biden-era policies on gender transition care for minors

-

Censorship Industrial Complex1 day ago

Censorship Industrial Complex1 day agoCanadian university censors free speech advocate who spoke out against Indigenous ‘mass grave’ hoax

-

Business19 hours ago

Business19 hours agoArgentina’s Milei delivers results free-market critics said wouldn’t work

-

Daily Caller1 day ago

Daily Caller1 day agoEx-FDA Commissioners Against Higher Vaccine Standards Took $6 Million From COVID Vaccine Makers

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoTrump signs order reclassifying marijuana as Schedule III drug

-

COVID-191 day ago

COVID-191 day agoFreedom Convoy protester appeals after judge dismissed challenge to frozen bank accounts