International

UN attacks stay-at-home motherhood as ‘gender inequality’

From LifeSiteNews

By Matt Lamb

“Care work remains undervalued and underpaid. The monetary value of women’s unpaid care work globally is at least $10.8 trillion annually, three times the size of the world’s tech industry”

Stay-at-home moms, and mothers in general, are victims of “gender inequality” and “gender-based violence” because of their dedication to their children, a far-left United Nations commission claimed.

The 68th session of the UN Commission on the Status of Women reportedly focused heavily on “unpaid care work,” according to journalist Kimberly Ells, writing at Mercator.

“I spent a week listening to an endless parade of events focused almost exclusively on ending poverty by eliminating ‘unpaid care work,’” Ells wrote.

“What is ‘unpaid care work,’ you might ask? It is work done in the home without specific monetary payment. Most people would call that kind of work simply being alive,” she wrote. “It could also be called running your own castle.”

The United Nations’ 2023 Agenda for Sustainable Development Goals lists “unpaid care work” as something that needs to be addressed.

“But the forces that converged at the United Nations this spring called it an atrocity,” she said. “To be an ‘unpaid care worker’—especially if you’re a woman—was seen as an affront to human decency,” she said. “And because on average women worldwide do more labour in the home than men, people in UN circles call this ‘gender inequality,’ ‘gender injustice,’ and even ‘gender-based violence.’”

Ells reported that the commission members wanted taxpayer-funded daycare, an idea she pointed out has Marxist roots.

While Karl Marx is most famous for being an opponent of capitalism, he was supportive of getting women working and out of the home, as was Friedrich Engels, who continued his advocacy after Marx’s death.

“In The Family, Private Property and State, Engels reiterated Marx’s argument that women could only achieve equality when ‘both possess legally complete equality of rights,’” International Socialism previously wrote.

“‘Then it will be plain that the first condition for the liberation of the wife is to bring the whole female sex back into public industry and that this in turn demands the abolition of the monogamous family as the economic unit of society,’” an article at the communist website stated, quoting Engels.

A 2019 United Nation’s Children’s Fund news release has demanded “universal childcare,” stating, “Universal access to affordable, quality childcare from the end of parental leave until a child’s entry into the first grade of school, including before- and after-care for young children and pre-primary programs [should be provided].”

The United Nations’ entities regularly push the idea that women are victims of “unpaid care work,” backing up Ells’ reporting for Mercator.

“On average, women spend around three times more time on unpaid care and domestic work than men,” a March 7 story at UN News stated. “The gendered disparities in unpaid care work are a profound driver of inequality, restricting women’s and girls’ time and opportunities for education, decent paid work, public life, rest and leisure.”

“Care work remains undervalued and underpaid. The monetary value of women’s unpaid care work globally is at least $10.8 trillion annually, three times the size of the world’s tech industry,” the UN blog claimed.

A November 2023 report suggested “climate change” is linked to this problem.

“The gender gap in power and leadership positions remains entrenched, and, at the current rate of progress, the next generation of women will still spend on average 2.3 more hours per day on unpaid care and domestic work than men,” a September 2023 UN report warned.

Women don’t want to be out of the household full-time

However, while the UN sees women at home taking care of their children and domestic duties as a problem – and daycare as a solution – moms do not.

“Only 32% of mothers prefer full-time work,” the Institute for Family Studies wrote in 2020, summarizing other polls.

Massive government subsidies for family leave and daycare do not appear to change the numbers, according to IFS’ report.

In Ireland, for example, 61% of mothers said they prefer part-time work, while another 12% said they prefer to not work at all.

Only 23% said they want to work full-time. Yet Ireland offers 45 hours per week of subsidized childcare.

Children being raised by a stay-at-home mom has also been linked to better school performance and fewer emotional problems.

Crime

Mexico’s Constitutional Crisis

Civitatensis

This is the situation Mexico faces today, but Mexico is hardly unique in confronting the challenge of criminal governance displacing state authority. Colombia spent decades battling FARC and cartel control over vast territories before slowly, painfully reclaiming sovereignty through a combination of military force and institution-building. Sicily lived under Mafia governance so complete that the Italian state effectively ceased to exist in many regions until the maxiprocesso trials of the 1980s demonstrated that the state could, if it chose, reassert authority. Afghanistan never successfully resolved the tension between state and warlord governance, leaving a vacuum that extremist organizations repeatedly exploited. Even the United States faced similar dynamics during Prohibition, when organized crime achieved such power that it effectively governed cities like Chicago and controlled elected officials at every level.

What distinguishes these cases from ordinary high-crime environments is the transition from criminal activity within a state to criminal governance replacing the state. When armed organizations collect taxes, regulate economic activity, administer their own justice, and determine who holds political office, they have become the de facto government regardless of constitutional fictions to the contrary. The question for any state facing this challenge is brutally simple: will it fight to restore its monopoly on legitimate violence, or will it accommodate the new reality through various forms of negotiated coexistence?

Colombia chose to fight, deploying military force under Plan Colombia while building investigative and prosecutorial capacity. The strategy took decades, cost thousands of lives, and required uncomfortable partnership with the United States. It also worked, transforming Colombia from a failing state into one of Latin America’s most dynamic economies. Sicily’s anti-Mafia campaign similarly required accepting that normal law enforcement had failed, that extraordinary measures (including aggressive use of military resources and suspension of certain procedural protections) were necessary, and that restoration of state authority was the prerequisite for everything else Italians valued about constitutional governance. Afghanistan never made that choice, instead attempting to negotiate with warlords and incorporate them into formal governance structures. The result was permanent instability and eventual state collapse.

The implications extend far beyond Mexico’s borders. Guatemala faces similar challenges with criminal organizations controlling substantial territory. El Salvador’s Nayib Bukele deployed extraordinary measures (mass arrests, suspension of certain rights) to break gang control, producing dramatic violence reductions that other states in the region are studying closely. Brazil’s favelas demonstrate how criminal governance can persist for generations within otherwise functional states when authorities accept de facto partition of sovereignty. And the United States watches nervously as fentanyl flows across a border it shares with a neighbor whose government may lack the capacity or will to control its own territory.

The Mexican case matters because Mexico is not a failed state in the traditional sense. It has functional institutions, a growing economy with healthy foreign investment, democratic elections, and sophisticated political culture. Yet armed criminal organizations control substantial portions of its territory and operate with such impunity that they assassinate elected officials while the national government insists it cannot respond forcefully because doing so would violate constitutional norms. If Mexico cannot resolve this tension between constitutional formalism and effective sovereignty, what hope exists for weaker states facing similar challenges?

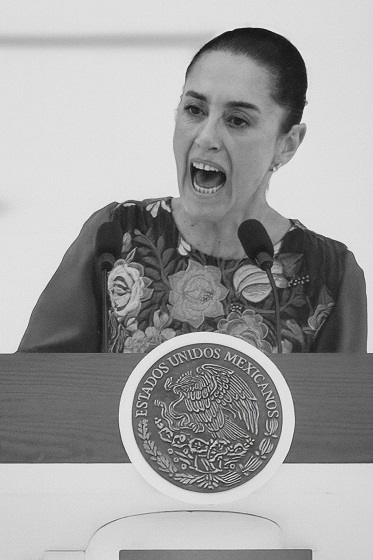

On November 5, 2025, Mexican President Claudia Sheinbaum stood before reporters at the National Palace and declared: “Regresar a la guerra contra el narco no es opción” (returning to the war against the narcos is not an option). The statement came in the wake of the assassination of Carlos Manzo, the mayor of Uruapan, Michoacán. It came as reports surfaced that the Trump administration was considering military operations against cartel infrastructure on Mexican soil. And it came as Mexico’s homicide rate continued to run at more than four times the threshold epidemiologists use to define a violence epidemic.

Sheinbaum’s position deserves serious engagement. She’s not wrong that Felipe Calderón’s 2006-2012 “war on drugs” produced catastrophic violence. She’s not wrong that militarized approaches lacking proper legal frameworks can violate constitutional rights. And she’s not wrong that sustainable security requires addressing “root causes,” not just symptoms.

She is, however, catastrophically wrong about the choice before Mexico. And her wrongness stems from a fatal confusion about constitutional order.

Mexico doesn’t have a crime problem. It has a sovereignty problem. In substantial portions of Mexican territory, the state does not govern. Criminal organizations do. They collect taxes through extortion. They administer justice through execution. They regulate economic activity through control of drug production, human trafficking, and legitimate businesses. They determine who holds political office through assassination.

The numbers tell part of the story. Mexico experienced over 190,000 homicides during the six-year term of Andrés Manuel López Obrador, Sheinbaum’s predecessor and political mentor. The country’s murder rate stands at approximately 24 per 100,000 inhabitants. The World Health Organization considers death rates above 5.8 per 100,000 to constitute an epidemic. Mexico has sustained epidemic-level violence for nearly two decades.

But raw numbers understate the constitutional crisis. In Sinaloa, a cartel war produced 150 homicides in a single month following the capture of “El Mayo” Zambada. In Guanajuato, despite billions in foreign investment from companies like GM and Mazda, the state recorded over 3,000 murders in 2023 alone. In Michoacán, mayors serve at cartel pleasure. Those who displease them, like Carlos Manzo, are killed despite state security protection.

This is not “high crime.” It is contested sovereignty. And it demands one asks: what is a constitutional order? What is a constitution for when armed groups, not legitimate governments, determine who lives, dies, and governs?

To her credit, Sheinbaum hasn’t dismissed security concerns. She’s articulated a principled constitutional objection to militarized approaches that merits some consideration. Her core legal argument runs like this: The “war against the narcos” that Felipe Calderón declared in December 2006 was “fuera de la ley” (outside the law) because it amounted to “permiso para matar, sin ningún juicio” (permission to kill without any trial). When the state operates under a “war” framework rather than a law enforcement framework, it abandons the due process guarantees that constitute the bedrock of constitutional governance.

Mexican constitutional law, like that of most democracies, distinguishes sharply between policing and warfare. Police operate under criminal procedure codes. They make arrests. They gather evidence. They bring charges. Suspects receive trials. This framework protects the innocent and the guilty from arbitrary state violence. Military operations, by contrast, operate under rules of engagement typically designed for armed conflict with foreign enemies. The objective is to defeat or eliminate the enemy, not to arrest and prosecute them. When Calderón appeared in military uniform to declare war on the cartels, he was replacing constitutional law enforcement with unconstitutional military operations against Mexican citizens.

The empirical record supports Sheinbaum’s concern about outcomes. Calderón’s six-year term saw intentional homicides increase by 148%. The militarization occurred “sin marco jurídico” (without legal framework), producing extrajudicial executions and systematic human rights violations. Rather than defeating the cartels, the offensive fragmented them, creating dozens of smaller, more violent organizations fighting over territory.

Sheinbaum characterizes calls to return to this approach as “autoritarios, es ir hacia el fascismo, donde no hay estado de derecho y donde todo es extrajudicial” (authoritarian, going toward fascism, where there is no rule of law and where everything is extrajudicial). Once you declare “war” on your own citizens, even criminal ones, you’ve abandoned the fundamental premise that the state’s monopoly on force must operate through law, not above it.

Her alternative strategy, as far as one can see, rests on four pillars: prevention through social programs, intelligence-led investigation, coordination between government levels, and consolidation of the National Guard. Rather than “permission to kill,” her approach promises to “atender las causas” (address the causes) of violence while respecting human rights and constitutional constraints. She even invokes sovereignty, rejecting U.S. offers of deeper cooperation: “Aceptamos la ayuda en información, en inteligencia; pero la intervención, no” (We accept help with information and intelligence, but intervention, no). Mexico, she insists, is a sovereign nation that will solve its problems through constitutional means.

This is a serious position, grounded in genuine constitutional concerns and supported by real evidence of past failures. It deserves better than dismissive responses about being “soft on crime.” It also deserves to be demolished, because it represents constitutional formalism untethered from constitutional purpose.

The problem with Sheinbaum’s argument is that it suffers from a catastrophic inversion of constitutional hierarchy. She treats procedural rights as the foundation of constitutional order when they are the product of constitutional order. Constitutions don’t exist to guarantee procedural arrests and trials. They exist to secure the conditions under which civilized life (including trials) becomes possible. Those conditions require that the state, not armed criminal bands, exercise a monopoly on legitimate violence within its territory. When that legitimate monopoly collapses, the constitutional order has already failed. Insisting on procedural niceties while armed groups govern entire regions isn’t defending a constitution. It’s presiding over its irrelevance.

Consider Sheinbaum’s claim that using military force against cartels constitutes “permission to kill without trial.” This framing would be apt if the cartels were ordinary criminal suspects who could be arrested, charged, and tried. But that’s not what cartels are. Cartels are para-military insurgent organizations that control territory, maintain armed forces, collect taxes, and administer parallel governance. Force and murder are their currency. When cartel soldiers operate checkpoints, when they regulate who can do business in “their” territory, when they execute those who disobey “their” laws, they’re not committing crimes. They’re exercising extra governmental authority.

No one demands that lawful police obtain arrest warrants before returning fire against active shooters. When armed groups engage in sustained territorial control and firefights with security forces, responding with military force isn’t “extrajudicial execution.” It’s the state exercising its foundational obligation to maintain a monopoly on legitimate violence. Sheinbaum’s proceduralism would make perfect sense in a functioning state where criminals operate as individuals within a legal order they cannot overthrow. It makes no sense when armed organizations have already overthrown that legal order in substantial territories. One cannot guarantee due process to people living under cartel governance because cartels don’t recognize due process. The state’s obligation is to restore the conditions under which due process can function.

The empirical claims supporting Sheinbaum’s position also require scrutiny rather than acceptance. She points to declining homicide statistics as evidence her approach works. The government claims a 37% reduction in the daily homicide rate between September 2024 and October 2025. But this statistic conceals more than it reveals. Disappearances rose by 20% during the same period. Bodies never found don’t appear in homicide statistics, creating a perverse incentive for cartels to disappear victims rather than leave corpses. Using homicide data to measure security when disappearances are rising is like measuring flood damage by counting only the houses you can still see.

Even accepting the government’s numbers at face value, Mexico remains mired in catastrophic violence. Celebrating a decline from apocalyptic to merely catastrophic violence while cartels control substantial territory is like a cancer patient celebrating that their tumor is growing more slowly. Sheinbaum’s historical narrative blames Calderón’s confrontation for causing violence while ignoring the counterfactual. The cartels were already growing in power and territorial control before 2006. Calderón confronted them; his successors accommodated them. Violence during confrontation doesn’t prove that accommodation would have prevented it. The violence might simply have taken different forms (slower-burning, less visible, but equally devastating) as cartels consolidated control.

The Sheinbaum-López Obrador approach has now governed Mexico for seven years. The result? Mexico’s violence remains at epidemic levels. Cartels control more territory than before. State officials continue to be assassinated. And the government’s response is to insist that their approach is working because things aren’t getting worse as quickly. This is the logic of managed decline dressed up as policy success.

The contradiction becomes most apparent when examining Sheinbaum’s invocation of sovereignty. She rejects U.S. assistance beyond intelligence sharing, proclaiming that Mexico is “un país soberano e independiente” (a sovereign and independent nation). But sovereignty doesn’t mean the absence of foreign forces on your territory. It means the state, not competing armed groups, exercises legitimate authority over territory. When cartels control checkpoints, collect taxes, administer justice, and determine who can hold office, they are the sovereign. Mexico has not lost sovereignty to potential U.S. intervention. It has already lost sovereignty to the cartels in substantial portions of its territory.

Sheinbaum’s position amounts to: “We will defend Mexican sovereignty by ensuring that Mexican criminal organizations, rather than the Mexican state, govern Mexican territory.” This isn’t nationalism. It’s surrender with flags.

Her emphasis on “addressing root causes” through social programs like Jóvenes Construyendo el Futuro (Youth Building the Future) reflects a similar misunderstanding of the challenge Mexico faces. Social programs make sense for preventing the next generation from joining cartels. They do nothing about the current generation of cartel soldiers already controlling territory, extracting wealth, and terrorizing populations. When your house is burning, you don’t address the root causes of combustion. You extinguish the fire. Once it’s out, you can investigate electrical wiring.

The poverty-causation theory is also empirically weak. Many poor regions of Mexico have low violence. Many cartel strongholds aren’t the poorest areas. Guanajuato, with billions in foreign investment, leads the nation in murders. The cartels aren’t driven by poverty. They’re multi-billion dollar enterprises driven by American demand for drugs. No job training program addresses that economic engine. More fundamentally, “addressing root causes” during an active insurgency confuses peacetime governance with wartime emergency. It’s the logic of a government that has already accepted permanent cartel sovereignty and now seeks merely to manage its fraying consequences.

The legal framework objection reveals similar evasion. Sheinbaum argues that Calderón’s approach lacked proper legal framework. Fine. Then create one. The Mexican Congress is controlled by Morena, Sheinbaum’s party. If the problem with military operations against cartels is the absence of legal framework, the solution is obvious: pass legislation explicitly authorizing such operations with clear rules of engagement, judicial oversight, accountability mechanisms, and defined criteria for when military force is appropriate.

But Sheinbaum doesn’t propose this. Her argument amounts to: “We can’t use force because there’s no legal framework, and we won’t create a legal framework because we oppose using force.” This is circular reasoning designed to avoid a hard choice, not a principled constitutional position. The reality is that every constitutional democracy maintains legal frameworks for deploying military force in extraordinary circumstances. The question isn’t whether such frameworks can exist consistent with constitutional governance (they manifestly can). The question is whether Mexico’s government has the will to create and use them. Sheinbaum’s answer appears to be no, which means her constitutional objections are pretexts, not principles.

Strip away the constitutional theory and what remains is a simple moral question: Does the Mexican government owe its citizens protection from cartel violence? Citizens in cartel-controlled regions live under constant extortion. They cannot conduct business freely. They face arbitrary violence with no recourse to justice. They cannot choose their leaders, who face assassination if they displease cartel bosses. These aren’t abstract harms. They’re daily realities for millions of Mexicans.

When Sheinbaum declares that military action would be “authoritarian” or “fascist,” she ignores that these citizens already live under murderous authoritarianism and fascism, administered by cartels, not the state. Her refusal to deploy state power to protect them doesn’t defend their rights. It abandons them to vile predation. The government’s response to the Uruapan mayor’s assassination is revealing. Despite having security protection (one bodyguard even killed an attacker), Carlos Manzo was murdered. The state cannot protect its own officials. Yet Sheinbaum’s reaction is not to strengthen state capacity but to reject calls for stronger action as illegitimate.

Citizens in Michoacán protested, expressing understandable “indignación por lo ocurrido” (indignation at what happened). Sheinbaum’s response? She questioned whether protest convocations were “legitimate,” suggesting they were politically motivated by opposition forces. This is the posture of a government that has accepted cartel sovereignty as immutable reality and now treats citizens demanding protection as the problem.

The purpose of government is not to guarantee trials. It’s to secure the conditions under which civilized life becomes possible. Those conditions require that the state maintain a monopoly on legitimate violence. When armed groups seize territory, the state’s first obligation is to restore its monopoly on force. Not because violence is good, but because it’s the prerequisite for everything else we value. You cannot have economic development while businesses pay extortion. You cannot have democratic governance while officials face assassination. You cannot have justice while cartels administer their own law.

Sheinbaum’s approach defends the form of constitutional governance while surrendering its substance. It’s constitutional suicide masked as principle. The alternative is a properly designed legal framework for deploying overwhelming state force to restore territorial control, followed by institution-building to maintain it. This would involve clear legislative authorization for military operations against armed groups controlling territory, rules of engagement that distinguish between legitimate use of force and extrajudicial killing, judicial oversight to ensure accountability, coordination with competent international partners (the U.S., obviously, but not exclusively), massive investment in investigative capacity and prosecutorial infrastructure, and once territorial control is restored, social programs and economic development to prevent recurrence.

The current approach guarantees only one thing: continued cartel sovereignty over substantial Mexican territory, and continued abandonment of millions of citizens to predation.

The lessons extend beyond Mexico. Other Latin American states watch carefully as Mexico demonstrates what happens when governments prioritize procedural correctness over effective sovereignty. Guatemala faces similar cartel penetration and must decide whether to follow Mexico’s accommodation or chart a different course. Brazil’s approach to favela governance shows how partition of sovereignty can become permanent if accepted for too long. Even wealthy democracies face versions of this challenge when criminal organizations achieve sufficient power that normal law enforcement proves inadequate.

The question isn’t unique to developing states or regions with weak institutions. It’s a central feature of political life. The rule of law depends on someone willing to enforce it. Once the state declines that obligation, it cedes the field to those who recognize no law but power. That’s not constitutional governance. It’s surrender.

|

|||||

|

|||||

| Select writings and discussions on regional politics and culture in Latin America |

Crime

FBI Seizes $13-Million Mercedes Unicorn From Ryan Wedding’s Narco Network

In the aftermath of their second Ryan Wedding indictment bombshell, the FBI’s Los Angeles field office dropped one of the most surreal photos of the Giant Slalom case this week: a silver, open-top Mercedes-Benz CLK-GTR roadster — valued at roughly US$13 million — parked under fluorescent lights in a federal impound warehouse.

Agents say the 2002 Mercedes CLK-GTR was seized from the organization of Ryan James Wedding, the former Canadian Olympic snowboarder now on the FBI’s Ten Most Wanted list.

Other stunning details in the new indictment — which alleges that a Canadian lawyer advised Wedding to kill a federal witness, whom The Bureau has identified as a convicted fentanyl trafficker from Montreal who ran a cartel network whose “sole purpose” was exporting narcotics including MDMA from Canada to the United States — include claims that Wedding is allegedly protected by a Mexican businessman with ties to senior Mexican government officials.

As one of The Bureau’s U.S. sources put it, that allegation suggests the Mexican businessman is viewed as a more important Sinaloa Cartel boss than Wedding himself.

As for the Mercedes, online records show it is one of only six CLK-GTR roadsters ever built worldwide, making it one of the rarest and most valuable cars the U.S. government has ever confiscated.

The car itself is a relic from the wildest corner of 1990s motorsport.

Mercedes and AMG created the CLK-GTR for the FIA GT1 series — essentially a Le Mans race car thinly disguised as a road car.

The road-legal “Straßenversion” models were hand-assembled at AMG’s facility in Affalterbach, Germany, in the late 1990s, with a small batch of six roofless roadsters completed from 2002 onward. Under the carbon-fiber skin sits a 6.9-liter V-12 making around 600 horsepower, good for 0–100 km/h in about 3.8 seconds and a top speed of roughly 200 mph.

When new, the CLK-GTR was listed by Guinness World Records as the most expensive production car on sale, at about US$1.5 million; recent auction results put similar roadsters around US$10.2 million, with pre-sale estimates up to US$13 million.

For U.S. authorities, this is evidence. The U.S. Treasury Department, which has now sanctioned Wedding and a string of associates, says he “has laundered his illicit profits through an extensive transatlantic network of businesses and associates, channeling drug proceeds into luxury assets such as cars and motorcycles that are concealed around the world.” Treasury identifies two key money men behind that network: Toronto jeweller Rolan Sokolovski and former Italian special forces member Gianluca Tiepolo.

Sokolovski, Treasury says, handled the books for Wedding’s organization and washed its funds through his Toronto jewelry company, 2351885 Ontario Inc., which trades as Diamond Tsar, while also moving millions in drug proceeds via cryptocurrency to mask the origin of the money.

Tiepolo allegedly “worked closely with Sokolovski to procure and manage Wedding’s physical assets, including high-end vehicles,” and held “millions of dollars in Wedding’s property under his own name to conceal these assets from authorities.”

Tiepolo owns Italian and U.K. firms — Stile Italiano S.R.L. and TMR Ltd. — that trade in luxury motorcycles and cars, and he founded Windrose Tactical, a training outfit that has hosted Wedding’s alleged hitmen.

The Bureau is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

-

International2 days ago

International2 days ago“The Largest Funder of Al-Shabaab Is the Minnesota Taxpayer”

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoAlberta introducing dual practice health care model to increase options and shorten wait times while promising protection for publicly funded services

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoBoris Johnson Urges Ukraine to Continue War

-

Great Reset1 day ago

Great Reset1 day agoRCMP veterans’ group promotes euthanasia presentation to members

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoBeijing’s blueprint for breaking Canada-U.S. unity

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoTaxpayers paying wages and benefits for 30% of all jobs created over the last 10 years

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoIs affirming existing, approved projects truly the best we can do in Canada?

-

MAiD1 day ago

MAiD1 day agoHealth Canada suggests MAiD expansion by pre-approving ‘advance requests’