Alberta

‘The saving grace for agriculture’: Farmers look to irrigation amid climate woes

CALGARY — Sean Stanford’s wheat farm just south of Lethbridge, Alta. falls within the far left corner of Palliser’s Triangle — an expanse of prairie grassland encompassingmuch of southeast Alberta, a swath of southern Saskatchewan, and the southwest corner of Manitoba.

The area is named for explorer Capt. John Palliser, who in 1857, famously declared the entire region a wasteland — so hot and arid that no crops would ever grow.

More than 160 years later, with parts of the prairie provinces suffering through another summer of drought conditions, Stanford’s farm is certainly dry.

“I think we’ve had three inches of rain since we started seeding. It’s been pretty dismal, honestly,” he said in an interview in July.

But Stanford is growing crops, thanks to a series of small sprinklers, attached to a large pipe and powered by an electric motor that disperse water from a nearby irrigation canal over some of his fields.

“Hopefully this fall I’m going to put up a little more irrigation on a couple more fields of mine,” Stanford said, adding he expects his non-irrigated, or dryland, acres to yield about a third of what his irrigated acres yield this year.

“You’re able to mitigate your risks a lot more. Moisture, in my mind, is the No. 1 driving factor in making a crop or not.”

Drought insurance

The economy of southern Alberta would not exist as it does today without irrigation. As early as the late 1800s, public and private investors began to build a vast network of dams, reservoirs, canals and pipelines that opened the area up for settlement and turned John Palliser’s so-called wasteland into a viable farming region.

According to the Alberta WaterPortal Society, there are now more than 8,000 kilometres of conveyance works and more than 50 water storage reservoirs devoted to managing 625,000 hectares of irrigated land in the province.

And while that’s just over five per cent of the province’s total agricultural land base, it accounts for 19 per cent of Alberta’s gross primary agricultural production. Farmers in irrigation districts are able to produce high-value, specialized crops such as sugar beets and greenhouse vegetables.

“There are places that we simply wouldn’t have an agriculture industry if irrigation wasn’t happening — parts of the province are so dry that we wouldn’t be growing anything,” said Richard Phillips, general manager of the Bow River Irrigation District, which owns and operates several hundred kilometres of earth canals and water pipelines, as well as several reservoirs, in the Vauxhall area southeast of Calgary.

“We certainly wouldn’t be growing the crops that are being grown.”

In drier-than-normal years — like the one southeast Alberta is experiencing right now — irrigation is often the only thing standing in the way of full-fledged agricultural disaster, Phillips added.

“If it’s a drought year, dryland produces next to nothing, whereas the irrigated areas are still producing excellent crops,” Phillips said.

“It’s great drought insurance, if you want to think of it that way.”

A growing need

According to Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada’s most recent drought monitor report, 76 per cent of the country’s agricultural landscape is either abnormally dry or experiencing moderate to severe drought this summer.

Some farmers, depending on the region, are dealing with their third or even fourth consecutive year of drought — with 2021 being an exceptionally bad year that saw production of some crops in Canada fall to their lowest level in more than a decade.

That’s part of the reason behind a recent push to modernize and expand irrigation infrastructure in this country.

In Alberta, in 2020, the province and the federal government through the Canada Infrastructure Bank announced a $932-million project to rehabilitate older irrigation equipment in the province, as well as construct or enlarge up to four off-stream irrigation storage reservoirs.

Saskatchewan has also announced a $4-billion project to double the amount irrigable land in the province.

Agriculture Canada predicts that changes in temperature and precipitation patterns due to climate change will increase reliance on irrigation and water-resource management in years to come — most notably across the Prairies and the interior of British Columbia, but “also in regions where there has not traditionally been a need to irrigate.”

Jodie Parmar, head of project development for Western Canada with the Canada Infrastructure Bank, said even Ontario and some of the Atlantic provinces have expressed interest in exploring irrigation projects recently.

“When I engaged in 2020 with provincial governments, in Western Canada in particular, what I heard from them was the need to focus on agriculture and agri-food,” Parmar said.

“And within that sub-sector, irrigation was their top ask.”

The limits of irrigation

Parmer said irrigation can not only be used to bring water to areas that don’t have enough, it can also improve the usage of the water that is available.

With climate change, for example, glaciers high in the Rocky Mountains are melting earlier in the season — and not at the time of year when farmers actually need the resulting runoff water. With irrigation, the water from those early-melting glaciers can be diverted and harnessed in reservoirs to be used for agriculture when it’s actually needed.

But not everyone believes irrigation can solve all of agriculture’s woes — at least, not without a price.

Even with effective water use management, there’s a limit to how much water can be drawn from a single source — and a limit to how much expansion of irrigation the public will tolerate, said Maryse Bourgault, an agronomist at the University of Saskatchewan

“In Saskatchewan, (advocates) talk about Lake Diefenbaker being used for irrigation. But Lake Diefenbaker is also very much involved in tourism,” she said.

“So how will the general public feel about us draining Lake Diefenbaker for irrigation?”

Bourgault added that over-irrigating can also raise the water table of the soil, and when that water evaporates, it leaves salts behind. She said in parts of the world, landscapes and ecosystems have suffered long-term damage.

“So I don’t believe (that it is a solution),” Bourgault said.

“I think at some point you’re going to overdo it. Even if you have the best management, at some point, nature happens.”

Agricultural lifeline

Irrigation is currently responsible for about 70 per cent of freshwater withdrawals worldwide. According to the Princeton Environmental Institute, about 90 per cent of water taken for residential and industrial uses eventually returns to the aquifer, but only about one-half of the water used for irrigation is reusable.

The remainder evaporates, is lost through leaky pipes or otherwise removed from the water cycle.

Bourgault said instead of expanding irrigation, farmers should be seeking to mitigate the effects of climate change through improved crop genetics and alternative farming practices like cover cropping, which can reduce the amount of moisture lost through evaporation.

Still, for farmers like Stanford, who have spent much of this past summer anxiously watching heat-shimmering skies for any hint of rain, irrigation is nothing less than a lifeline.

“If they could get some irrigation acres opened up all the way to the Saskatchewan border and beyond, that would be a huge benefit,” Stanford said.

“To have more moisture, if it’s not going to rain anymore around here, is going to be the saving grace for agriculture in this area.”

This report by The Canadian Press was first published Aug. 13, 2023.

Amanda Stephenson, The Canadian Press

Alberta

High costs, low returns – Canada’s wildly expensive emissions cap

In this new commentary, Director of Energy, Natural Resources, and Environment Heather Exner-Pirot reveals why the Canadian government’s oil and gas emissions cap isn’t just expensive – it’s economic insanity.

Canada is the world’s third-largest exporter of oil, fourth-largest producer, and top source of imports to the United States. Much of Canada’s oil wealth is concentrated in the oil sands in northern Alberta, which hosts 99 percent of the country’s enormous oil endowment: about 160 billion barrels of proven reserves, of a total resource of approximately 1.8 trillion barrels. This is the major source of oil to the United States refinery complex, a large part of which is optimized for the oil sands’ heavy oil.

Reliability of energy supply has remerged as a major geopolitical issue. Canadian oil and gas is an essential component of North American energy security. Yet a proposed cap on emissions from the sectors promises to cut Canadian production and exports in the years ahead. It would be hard to provide less environmental benefit for a higher economic and security cost. There are far better ways to reduce emissions while maintaining North America’s security of energy supply.

The high cost of the cap

In 1994 a Liberal federal government, Alberta provincial conservative government and representatives from the oil and gas industry, working together through the national oil sands task force, developed A New Energy Vision for Canada. Their efforts turned what was then a middling resource into a trillion dollar nation-building project. Production has increased tenfold since the report came out.

The task force acknowledged the need for industry to “put its best efforts toward … reducing greenhouse gas emissions.” However, it also expected governments to “understand” that there “is no benefit to Canada or to the environment to have production and value-added processing done outside of the country in less efficient jurisdictions … policies set by regulator must not result in discouraging oil sands production.”

As part of its efforts to meet its climate goals under the Paris Accord, the Canadian government proposed a regulatory framework for an emissions cap on the oil and gas sector in December 2023. It set a legally binding limit on greenhouse gas emissions, targeting a 35 to 38 percent reduction from 2019 levels by 2030 for upstream operations, through regulations to be made under the Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999 (CEPA).

The federal government has not yet finalized its proposed regulations. However, industry experts and economists have criticized the current iteration as logistically unworkable, overly expensive, and likely to be challenged as unconstitutional. In effect, this policy layers a cap-and-trade system for just one sector (oil and gas) on top of a competing carbon pricing mechanism (the large-emitter trading systems, often referred to as the industrial carbon price), a discriminatory practice that also undermines the entire economic rationale of a carbon pricing system.

While the Canadian government has maintained that it is focused on reducing emissions rather than production – the latter of which would put it at odds with provincial jurisdiction over non-renewable resources – a series of third party analyses as well as the Parliamentary Budget Office’s own impact assessment find it would indeed constrain Canadian oil and gas production. The economic cost of the emissions cap far exceeds any corresponding benefit in reduced emissions.

How much will the emissions cap cost in terms of dollar per tonne of carbon in avoided emissions, both domestically and globally? Based solely on the cost to the Canadian economy, we estimate the emission cap is equivalent to a C$2,887/tonne carbon price by 2032.

Assuming no impact on global demand and full substitution by non-Canadian crudes, it finds that the cost of each tonne of carbon displaced globally is between C$96,000 to C$289,000 for oil sands bitumen production. For displaced Canadian conventional and natural gas, the cost is infinite, i.e. global emissions would actually be higher for every barrel or unit of Canadian oil and gas displaced with competitor products as a result of the emissions cap.

Canadian oil and gas emissions reduction efforts

The oil and gas sector is the highest emitting economic sector in Canada. However, it has made substantial efforts to reduce emissions over the past two decades and is succeeding. Absolute emissions in the sector peaked in 2014, despite production growing by over a million barrels of oil equivalent since (see Figure 1).

Figure 1 Indexed greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (and gross domestic product (GDP) at basic prices, for the oil and gas extraction industry, 2009 to 2022 (2009 = 100). Source: Statistics Canada 2024.

Figure 1 Indexed greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions (and gross domestic product (GDP) at basic prices, for the oil and gas extraction industry, 2009 to 2022 (2009 = 100). Source: Statistics Canada 2024.

Much of this success can be attributed to methane capture, particularly in the natural gas and conventional oil sectors, where absolute emissions peaked in 2007 and 2014 respectively.

Since 2014, the oil sands have dramatically increased production by over a million barrels per day, but at the same time have reduced the emissions per barrel every year, leaving the absolute emissions of the oil and gas sector relatively flat. The oil sands are performing well vis-à-vis their international peers, seeing their emissions per barrel decline by 30 percent since 2013, compared to 21 percent for global majors and 34 percent for US E&Ps (exploration and production companies) (see Figure 2).

Figure 2 Indexed Oil Sands GHG relative intensity trend (2013=100). Source: BMO Capital Markets, “I Want What You Got: Canada’s Oil Resource Advantage,” April 2025

Figure 2 Indexed Oil Sands GHG relative intensity trend (2013=100). Source: BMO Capital Markets, “I Want What You Got: Canada’s Oil Resource Advantage,” April 2025

On an emissions intensity absolute basis, the oil sands have significantly outperformed their peers, shaving off 25kg/barrel of emissions since 2013 (see Figure 3) and more than 65kg/barrel since the oil sands task force wrote their report in 1994.

As emissions improvements from methane reductions plateau, the oil sands are likely to outperform their conventional peers in emissions per barrel reductions going forward. The sector is working on strategies such as solvent extraction and carbon capture and storage that, if implemented, would reduce the life-cycle emissions per barrel of oil sands to levels at or below the global crude average.

Figure 3 Emissions intensity absolute change (kg CO2e/bbl) (2013–24E) Source: BMO Capital Markets, 2025

Figure 3 Emissions intensity absolute change (kg CO2e/bbl) (2013–24E) Source: BMO Capital Markets, 2025

The high cost of the cap

Several parties have analyzed the proposed emissions cap to determine its economic and production impact. The results of the assessments vary widely. For the purposes of this commentary we rely on the federal Office of the Parliamentary Budget Officer (PBO), which published its analysis of the proposed emissions cap in March 2025. Helpfully, the PBO provided a table summarizing the main findings of the various analyses (see Table 1).

The PBO found that the required reduction in upstream oil and gas sector production levels under an emissions cap would lower real gross domestic product (GDP) in Canada by 0.33 percent in 2030 and 0.39 percent in 2032, and reduce nominal GDP by C$20.5 billion by 2032. The PBO further estimated that achieving the legal upper bound would reduce economy-wide employment in Canada by 40,300 jobs and full-time equivalents by 54,400 in 2032.

Table 2 Comparison of estimated impacts of the proposed emissions cap in 2030. Source: PBO 2025

Table 2 Comparison of estimated impacts of the proposed emissions cap in 2030. Source: PBO 2025

However, the PBO does not estimate the carbon price per tonne of emissions reduced. This is a useful metric as Canadians have become broadly familiar with the real-world impacts of a price on carbon. The federal government quashed the consumer carbon price at $80/tonne in March 2025, ahead of the federal election, due to its unpopularity and perceived impacts on affordability. The federal carbon pricing benchmark is scheduled to hit C$170 in 2030. ECCC has quantified the damages of a tonne of carbon dioxide – referred to as the “Social Cost of Carbon” – as C$294/tonne.

Based on PBO assumptions that the emissions cap will reduce emissions by 7.1MT and reduce GDP by $20.5 billion in 2032, the implied carbon price is C$2,887/tonne.

Emissions cap impact in a global context

Even this eye-popping figure does not tell the full story. The Canadian oil and gas production that must be withdrawn to meet the requirements of the emissions cap will be replaced in global markets from other producers; there is no reason to assume the emissions cap will affect global demand.

Based on life-cycle GHG emissions of the sample of crudes used in the US refinery complex, Canadian oil sands produce only 1 to 3 percent higher emissions than a global average[1] (see Figure 4), with some facilities producing lower emissions than the average barrel.

Figure 4 Life Cycle GHG emissions of crude oils (kg CO2e/bbl). Source: BMO Capital Markets 2025

Figure 4 Life Cycle GHG emissions of crude oils (kg CO2e/bbl). Source: BMO Capital Markets 2025

As such, the emissions cap, if applied just to oil sands production, would only displace global emissions of 71,000 to 213,000 tonnes (1 to 3 percent of 7.1MT). At a cost of C$20.5 billion for those global emissions reductions, the price of carbon is equivalent to C$96,000 to C$289,000 per tonne (see Figure 5).

Figure 5 Cost per tonne of emissions cap behind domestic carbon all (left) and post-global crude substitution (right)

Figure 5 Cost per tonne of emissions cap behind domestic carbon all (left) and post-global crude substitution (right)

For any displaced conventional Canadian crude oil or natural gas, the situation becomes absurd. Because Canadian conventional oil and natural gas have a lower emissions intensity than global averages, global product substitutions resulting from the emissions cap would actually serve to increase global emissions, resulting in an infinite price per tonne of carbon.

The C$100k/tonne carbon price estimate is probably low

We believe our assessment of the effective carbon price of the emissions cap at C$96,000+/tonne to be conservative for the following reasons.

First, it assumes Canadian heavy oil will be displaced in global markets by an average, archetypal crude. In fact, it would be displaced by other heavy crudes from places like Venezuela, Mexico, and Iraq (see Figure 4), which have higher average emissions per barrel than Canadian oil sands crudes. In such a circumstance, global emissions would actually rise and the price per carbon tonne from an emissions cap on oil sands production would also effectively be infinite.

Secondly, emissions cap impact assumptions by the PBO are likely conservative. Those by ECCC, based on a particular scenario outlook, are already outdated. ECCC assumed a production loss of only 0.7 percent by 2030, with oil sands production hitting approximately 3.7 million barrels (MMbbls) per day of bitumen production in 2030. According to S&P Global analysis, that level is likely to be hit this year.[2]

S&P further forecasts oil sands production to reach 4.0 MMbbls by 2030, or about 300,000 barrels more than it produces today. This would represent a far lower production growth rate than the oil sands have experienced in the past five years. But assuming the S&P forecast is correct, production would need to decline in the oil sands by 8 percent to meet the emissions cap requirements. PBO assumed only a 5.4 percent overall oil and gas production loss and ECCC assumed only 0.7 percent, while Conference Board of Canada assumed an 11.1 percent loss and Deloitte assumed 11.5 percent (see Table 1). Production numbers to date more closely align with Conference Board of Canada and Deloitte projections.

Let’s make the Canadian oil and gas sector better, not smaller

The Canadian oil and gas sector, and in particular the oil sands, has a responsibility to do their part to reduce emissions while maintaining competitive businesses that can support good Canadian jobs, provide government revenues and diversify exports. The oil sands sector has re-invested for decades in continuous improvements to drive down production costs while improving its emissions per barrel.

It is hard to conceive of a more expensive and divisive way to reduce emissions from the sector and from the Canadian economy than the proposed emissions cap. Other expensive programs, such as Norway’s EV subsidies, the United Kingdom’s offshore wind contracts-for-difference, Germany’s Energiewende feed-in-tariffs and surcharges, and US Inflation Reduction Act investment tax credits, don’t come close to the high costs of the emissions cap on a price-per-tonne of carbon abated basis.

The emissions cap, as currently proposed, will make Canada’s oil and gas sector significantly less competitive, harm investment, and undermine Canada’s vision to be an energy superpower. This policy will also reduce the oil and gas sector’s capacity to invest in technologies that drive additional emission reductions, such as solvents and carbon capture, especially in our current lower price environment. As such it is more likely to undermine climate action than support it.

The federal and provincial governments have come together to advance a vision for Canadian energy in the past. In this moment, they have the opportunity once again to find real solutions to the climate challenge while harnessing the energy sector to advance Canada’s economic well-being, productivity, and global energy security.

About the author

Heather Exner-Pirot is Director of Energy, Natural Resources, and Environment at the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.

Alberta

Calgary taxpayers forced to pay for art project that telephones the Bow River

From the Canadian Taxpayers Federation

The Canadian Taxpayers Federation is calling on the City of Calgary to scrap the Calgary Arts Development Authority after it spent $65,000 on a telephone line to the Bow River.

“If someone wants to listen to a river, they can go sit next to one, but the City of Calgary should not force taxpayers to pay for this,” said Kris Sims, CTF Alberta Director. “If phoning a river floats your boat, you do you, but don’t force your neighbour to pay for your art choices.”

The City of Calgary spent $65,194 of taxpayers’ money for an art project dubbed “Reconnecting to the Bow” to set up a telephone line so people could call the Bow River and listen to the sound of water.

The project is running between September 2024 and December 2025, according to documents obtained by the CTF.

The art installation is a rerun of a previous version set up back in 2014.

Emails obtained by the CTF show the bureaucrats responsible for the newest version of the project wanted a new local 403 area code phone number instead of an 1-855 number to “give the authority back to the Bow,” because “the original number highlighted a proprietary and commercial relationship with the river.”

Further correspondence obtained by the CTF shows the city did not want its logo included in the displays, stating the “City of Calgary (does NOT want to have its logo on the artworks or advertisements).”

Taxpayers pay about $19 million per year for the Calgary Arts Development Authority. That’s equivalent to the total property tax bill for about 7,000 households.

Calgary bureaucrats also expressed concern the project “may not be received well, perceived as a waste of money or simply foolish.”

“That city hall employee was pointing out the obvious: This is a foolish waste of taxpayers’ money and this slush fund should be scrapped,” said Sims. “Artists should work with willing donors for their projects instead of mooching off city hall and forcing taxpayers to pay for it.”

-

conflict10 hours ago

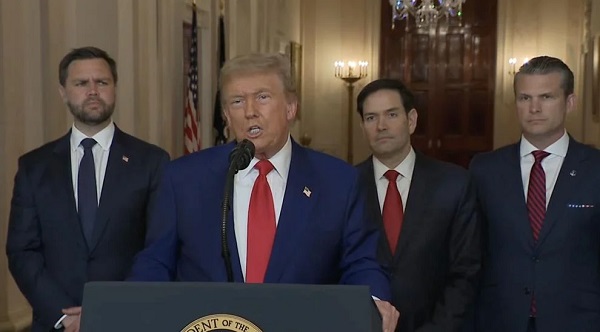

conflict10 hours agoPete Hegseth says adversaries should take Trump administration seriously

-

Business19 hours ago

Business19 hours agoHigh Taxes Hobble Canadian NHL Teams In Race For Top Players

-

Energy11 hours ago

Energy11 hours agoEnergy Policies Based on Reality, Not Ideology, are Needed to Attract Canadian ‘Superpower’ Level Investment – Ron Wallace

-

Health1 day ago

Health1 day agoKennedy sets a higher bar for pharmaceuticals: This is What Modernization Should Look Like

-

Automotive1 day ago

Automotive1 day agoCarney’s exercise in stupidity

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoOutrageous government spending: Canadians losing over 1 billion a week to interest payments

-

conflict19 hours ago

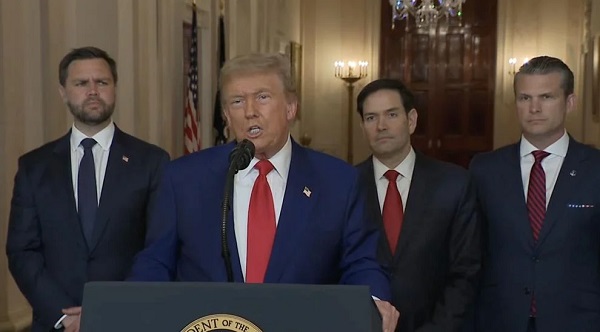

conflict19 hours ago“Spectacular military success”: Trump addresses nation on Iran strikes

-

conflict18 hours ago

conflict18 hours agoTrump urges Iran to pursue peace, warns of future strikes