Brownstone Institute

The Fraying of the Liberal International Order

From the Brownstone Institute

BY

International politics is the struggle for the dominant normative architecture of world order based on the interplay of power, economic weight and ideas for imagining, designing and constructing the good international society. For several years now many analysts have commented on the looming demise of the liberal international order established at the end of the Second World War under US leadership.

Over the last several decades, wealth and power have been shifting inexorably from the West to the East and has produced a rebalancing of the world order. As the centre of gravity of world affairs shifted to the Asia-Pacific with China’s dramatic climb up the ladder of great power status, many uncomfortable questions were raised about the capacity and willingness of Western powers to adapt to a Sinocentric order.

For the first time in centuries, it seemed, the global hegemon would not be Western, would not be a free market economy, would not be liberal democratic, and would not be part of the Anglosphere.

More recently, the Asia-Pacific conceptual framework has been reformulated into the Indo-Pacific as the Indian elephant finally joined the dance. Since 2014 and then again especially after the Russian invasion of Ukraine in February last year, the question of European security, political and economic architecture has reemerged as a frontline topic of discussion.

The return of the Russia question as a geopolitical priority has also been accompanied by the crumbling of almost all the main pillars of the global arms control complex of treaties, agreements, understandings and practices that had underpinned stability and brought predictability to major power relations in the nuclear age.

The AUKUS security pact linking Australia, the UK, and the US in a new security alliance, with the planned development of AUKUS-class nuclear-powered attack submarines, is both a reflection of changed geopolitical realities and, some argue, itself a threat to the global nonproliferation regime and a stimulus to fresh tensions in relations with China. British Prime Minister (PM) Rishi Sunak said at the announcement of the submarines deal in San Diego on March 13 that the growing security challenges confronting the world—“Russia’s illegal invasion of Ukraine, China’s growing assertiveness, the destabilising behaviour of Iran and North Korea”—“threaten to create a world codefined by danger, disorder and division.”

For his part, President Xi Jinping accused the US of leading Western countries to engage in an “all-around containment, encirclement and suppression of China.”

The Australian government described the AUKUS submarine project as “the single biggest investment in our defence capability in our history” that “represents a transformational moment for our nation.” However, it could yet be sunk by six minefields lurking underwater: China’s countermeasures, the time lag between the alleged imminence of the threat and the acquisition of the capability, the costs, the complexities of operating two different classes of submarines, the technological obsolescence of submarines that rely on undersea concealment, and domestic politics in the US and Australia.

Regional and global governance institutions can never be quarantined from the underlying structure of international geopolitical and economic orders. Nor have they proven themselves to be fully fit for the purpose of managing pressing global challenges and crises like wars, and potentially existential threats from nuclear weapons, climate-related disasters and pandemics.

To no one’s surprise, the rising and revisionist powers wish to redesign the international governance institutions to inject their own interests, governing philosophies, and preferences. They also wish to relocate the control mechanisms from the major Western capitals to some of their own capitals. China’s role in the Iran–Saudi rapprochement might be a harbinger of things to come.

The ”Rest” Look for Their Place in the Emerging New Order

The developments out there in “the real world,” testifying to an inflection point in history, pose profound challenges to institutions to rethink their agenda of research and policy advocacy over the coming decades.

On 22–23 May, the Toda Peace Institute convened a brainstorming retreat at its Tokyo office with more than a dozen high-level international participants. One of the key themes was the changing global power structure and normative architecture and the resulting implications for world order, the Indo-Pacific and the three US regional allies Australia, Japan, and South Korea. The two background factors that dominated the conversation, not surprisingly, were China–US relations and the Ukraine war.

The Ukraine war has shown the sharp limits of Russia as a military power. Both Russia and the US badly underestimated Ukraine’s determination and ability to resist (“I need ammunition, not a ride,” President Volodymyr Zelensky famously said when offered safe evacuation by the Americans early in the war), absorb the initial shock, and then reorganise to launch counter-offensives to regain lost territory. Russia is finished as a military threat in Europe. No Russian leader, including President Vladimir Putin, will think again for a very long time indeed of attacking an allied nation in Europe.

That said, the war has also demonstrated the stark reality of the limits to US global influence in organising a coalition of countries willing to censure and sanction Russia. If anything, the US-led West finds itself more disconnected from the concerns and priorities of the rest of the world than at any other time since 1945. A study published in October from Cambridge University’s Bennett Institute for Public Policy provides details on the extent to which the West has become isolated from opinion in the rest of the world on perceptions of China and Russia. This was broadly replicated in a February 2023 study from the European Council on Foreign Relations (ECFR).

The global South in particular has been vocal in saying firstly that Europe’s problems are no longer automatically the world’s problems, and secondly that while they condemn Russia’s aggression, they also sympathise quite heavily with the Russian complaint about NATO provocations in expanding to Russia’s borders. In the ECFR report, Timothy Garton-Ash, Ivan Krastev, and Mark Leonard cautioned Western decision-makers to recognise that “in an increasingly divided post-Western world,” emerging powers “will act on their own terms and resist being caught in a battle between America and China.”

US global leadership is hobbled also by rampant domestic dysfunctionality. A bitterly divided and fractured America lacks the necessary common purpose and principle, and the requisite national pride and strategic direction to execute a robust foreign policy. Much of the world is bemused too that a great power could once again present a choice between Joe Biden and Donald Trump for president.

The war has solidified NATO unity but also highlighted internal European divisions and European dependence on the US military for its security.

The big strategic victor is China. Russia has become more dependent on it and the two have formed an effective axis to resist US hegemony. China’s meteoric rise continues apace. Having climbed past Germany last year, China has just overtaken Japan as the world’s top car exporter, 1.07 to 0.95 million vehicles. Its diplomatic footprint has also been seen in the honest brokerage of a rapprochement between Iran and Saudi Arabia and in promotion of a peace plan for Ukraine.

Even more tellingly, according to data published by the UK-based economic research firm Acorn Macro Consulting in April, the BRICS grouping of emerging market economies (Brazil, Russia, India, China, South Africa) now accounts for a larger share of the world’s economic output in PPP dollars than the G7 group of industrialised countries (Canada, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, UK, USA). Their respective shares of global output have fallen and risen between 1982 and 2022 from 50.4 percent and 10.7 percent, to 30.7 percent and 31.5 percent. No wonder another dozen countries are eager to join the BRICS, prompting Alec Russell to proclaim recently in The Financial Times: “This is the hour of the global south.”

The Ukraine war might also mark India’s long overdue arrival on the global stage as a consequential power. For all the criticisms of fence-sitting levelled at India since the start of the war, this has arguably been the most successful exercise of an independent foreign policy on a major global crisis in decades by India. Foreign Minister S. Jaishankar even neatly turned the fence-sitting criticism on its head by retorting a year ago that “I am sitting on my ground” and feeling quite comfortable there. His dexterity in explaining India’s policy firmly and unapologetically but without stridency and criticism of other countries has drawn widespread praise, even from Chinese netizens.

On his return after the G7 summit in Hiroshima, the South Pacific and Australia, PM Narendra Modi commented on 25 May: “Today, the world wants to know what India is thinking.” In his 100th birthday interview with The Economist, Henry Kissinger said he is “very enthusiastic” about US close relations with India. He paid tribute to its pragmatism, basing foreign policy on non-permanent alliances built around issues rather than tying up the country in big multilateral alliances. He singled out Jaishankar as the current political leader who “is quite close to my views.”

In a complementary interview with The Wall Street Journal, Kissinger also foresees, without necessarily recommending such a course of action, Japan acquiring its own nuclear weapons in 3-5 years.

In a blog published on 18 May, Michael Klare argues that the emerging order is likely to be a G3 world with the US, China, and India as the three major nodes, based on attributes of population, economic weight and military power (with India heading into being a major military force to be reckoned with, even if not quite there yet). He is more optimistic about India than I am but still, it’s an interesting comment on the way the global winds are blowing. Few pressing world problems can be solved today without the active cooperation of all three.

The changed balance of forces between China and the US also affects the three Pacific allies, namely Australia, Japan, and South Korea. If any of them starts with a presumption of permanent hostility with China, then of course it will fall into the security dilemma trap. That assumption will drive all its policies on every issue in contention, and will provoke and deepen the very hostility it is meant to be opposing.

Rather than seeking world domination by overthrowing the present order, says Rohan Mukherjee in Foreign Affairs, China follows a three-pronged strategy. It works with institutions it considers both fair and open (UN Security Council, WTO, G20) and tries to reform others that are partly fair and open (IMF, World Bank), having derived many benefits from both these groups. But it is challenging a third group which, it believes, are closed and unfair: the human rights regime.

In the process, China has come to the conclusion that being a great power like the US means never having to say you’re sorry for hypocrisy in world affairs: entrenching your privileges in a club like the UN Security Council that can be used to regulate the conduct of all others.

Instead of self-fulfilling hostility, former Australian foreign secretary Peter Varghese recommends a China policy of constrainment-cum-engagement. Washington may have set itself the goal of maintaining global primacy and denying Indo-Pacific primacy to China, but this will only provoke a sullen and resentful Beijing into efforts to snatch regional primacy from the US. The challenge is not to thwart but to manage China’s rise—from which many other countries have gained enormous benefits, with China becoming their biggest trading partner—by imagining and constructing a regional balance in which US leadership is crucial to a strategic counterpoint.

In his words, “The US will inevitably be at the centre of such an arrangement, but that does not mean that US primacy must sit at its fulcrum.” Wise words that should be heeded most of all in Washington but will likely be ignored.

Brownstone Institute

Bizarre Decisions about Nicotine Pouches Lead to the Wrong Products on Shelves

From the Brownstone Institute

A walk through a dozen convenience stores in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, says a lot about how US nicotine policy actually works. Only about one in eight nicotine-pouch products for sale is legal. The rest are unauthorized—but they’re not all the same. Some are brightly branded, with uncertain ingredients, not approved by any Western regulator, and clearly aimed at impulse buyers. Others—like Sweden’s NOAT—are the opposite: muted, well-made, adult-oriented, and already approved for sale in Europe.

Yet in the United States, NOAT has been told to stop selling. In September 2025, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued the company a warning letter for offering nicotine pouches without marketing authorization. That might make sense if the products were dangerous, but they appear to be among the safest on the market: mild flavors, low nicotine levels, and recyclable paper packaging. In Europe, regulators consider them acceptable. In America, they’re banned. The decision looks, at best, strange—and possibly arbitrary.

What the Market Shows

My October 2025 audit was straightforward. I visited twelve stores and recorded every distinct pouch product visible for sale at the counter. If the item matched one of the twenty ZYN products that the FDA authorized in January, it was counted as legal. Everything else was counted as illegal.

Two of the stores told me they had recently received FDA letters and had already removed most illegal stock. The other ten stores were still dominated by unauthorized products—more than 93 percent of what was on display. Across all twelve locations, about 12 percent of products were legal ZYN, and about 88 percent were not.

The illegal share wasn’t uniform. Many of the unauthorized products were clearly high-nicotine imports with flashy names like Loop, Velo, and Zimo. These products may be fine, but some are probably high in contaminants, and a few often with very high nicotine levels. Others were subdued, plainly meant for adult users. NOAT was a good example of that second group: simple packaging, oat-based filler, restrained flavoring, and branding that makes no effort to look “cool.” It’s the kind of product any regulator serious about harm reduction would welcome.

Enforcement Works

To the FDA’s credit, enforcement does make a difference. The two stores that received official letters quickly pulled their illegal stock. That mirrors the agency’s broader efforts this year: new import alerts to detain unauthorized tobacco products at the border (see also Import Alert 98-06), and hundreds of warning letters to retailers, importers, and distributors.

But effective enforcement can’t solve a supply problem. The list of legal nicotine-pouch products is still extremely short—only a narrow range of ZYN items. Adults who want more variety, or stores that want to meet that demand, inevitably turn to gray-market suppliers. The more limited the legal catalog, the more the illegal market thrives.

Why the NOAT Decision Appears Bizarre

The FDA’s own actions make the situation hard to explain. In January 2025, it authorized twenty ZYN products after finding that they contained far fewer harmful chemicals than cigarettes and could help adult smokers switch. That was progress. But nine months later, the FDA has approved nothing else—while sending a warning letter to NOAT, arguably the least youth-oriented pouch line in the world.

The outcome is bad for legal sellers and public health. ZYN is legal; a handful of clearly risky, high-nicotine imports continue to circulate; and a mild, adult-market brand that meets European safety and labeling rules is banned. Officially, NOAT’s problem is procedural—it lacks a marketing order. But in practical terms, the FDA is punishing the very design choices it claims to value: simplicity, low appeal to minors, and clean ingredients.

This approach also ignores the differences in actual risk. Studies consistently show that nicotine pouches have far fewer toxins than cigarettes and far less variability than many vapes. The biggest pouch concerns are uneven nicotine levels and occasional traces of tobacco-specific nitrosamines, depending on manufacturing quality. The serious contamination issues—heavy metals and inconsistent dosage—belong mostly to disposable vapes, particularly the flood of unregulated imports from China. Treating all “unauthorized” products as equally bad blurs those distinctions and undermines proportional enforcement.

A Better Balance: Enforce Upstream, Widen the Legal Path

My small Montgomery County survey suggests a simple formula for improvement.

First, keep enforcement targeted and focused on suppliers, not just clerks. Warning letters clearly change behavior at the store level, but the biggest impact will come from auditing distributors and importers, and stopping bad shipments before they reach retail shelves.

Second, make compliance easy. A single-page list of authorized nicotine-pouch products—currently the twenty approved ZYN items—should be posted in every store and attached to distributor invoices. Point-of-sale systems can block barcodes for anything not on the list, and retailers could affirm, once a year, that they stock only approved items.

Third, widen the legal lane. The FDA launched a pilot program in September 2025 to speed review of new pouch applications. That program should spell out exactly what evidence is needed—chemical data, toxicology, nicotine release rates, and behavioral studies—and make timely decisions. If products like NOAT meet those standards, they should be authorized quickly. Legal competition among adult-oriented brands will crowd out the sketchy imports far faster than enforcement alone.

The Bottom Line

Enforcement matters, and the data show it works—where it happens. But the legal market is too narrow to protect consumers or encourage innovation. The current regime leaves a few ZYN products as lonely legal islands in a sea of gray-market pouches that range from sensible to reckless.

The FDA’s treatment of NOAT stands out as a case study in inconsistency: a quiet, adult-focused brand approved in Europe yet effectively banned in the US, while flashier and riskier options continue to slip through. That’s not a public-health victory; it’s a missed opportunity.

If the goal is to help adult smokers move to lower-risk products while keeping youth use low, the path forward is clear: enforce smartly, make compliance easy, and give good products a fair shot. Right now, we’re doing the first part well—but failing at the second and third. It’s time to fix that.

Addictions

The War on Commonsense Nicotine Regulation

From the Brownstone Institute

Cigarettes kill nearly half a million Americans each year. Everyone knows it, including the Food and Drug Administration. Yet while the most lethal nicotine product remains on sale in every gas station, the FDA continues to block or delay far safer alternatives.

Nicotine pouches—small, smokeless packets tucked under the lip—deliver nicotine without burning tobacco. They eliminate the tar, carbon monoxide, and carcinogens that make cigarettes so deadly. The logic of harm reduction couldn’t be clearer: if smokers can get nicotine without smoke, millions of lives could be saved.

Sweden has already proven the point. Through widespread use of snus and nicotine pouches, the country has cut daily smoking to about 5 percent, the lowest rate in Europe. Lung-cancer deaths are less than half the continental average. This “Swedish Experience” shows that when adults are given safer options, they switch voluntarily—no prohibition required.

In the United States, however, the FDA’s tobacco division has turned this logic on its head. Since Congress gave it sweeping authority in 2009, the agency has demanded that every new product undergo a Premarket Tobacco Product Application, or PMTA, proving it is “appropriate for the protection of public health.” That sounds reasonable until you see how the process works.

Manufacturers must spend millions on speculative modeling about how their products might affect every segment of society—smokers, nonsmokers, youth, and future generations—before they can even reach the market. Unsurprisingly, almost all PMTAs have been denied or shelved. Reduced-risk products sit in limbo while Marlboros and Newports remain untouched.

Only this January did the agency relent slightly, authorizing 20 ZYN nicotine-pouch products made by Swedish Match, now owned by Philip Morris. The FDA admitted the obvious: “The data show that these specific products are appropriate for the protection of public health.” The toxic-chemical levels were far lower than in cigarettes, and adult smokers were more likely to switch than teens were to start.

The decision should have been a turning point. Instead, it exposed the double standard. Other pouch makers—especially smaller firms from Sweden and the US, such as NOAT—remain locked out of the legal market even when their products meet the same technical standards.

The FDA’s inaction has created a black market dominated by unregulated imports, many from China. According to my own research, roughly 85 percent of pouches now sold in convenience stores are technically illegal.

The agency claims that this heavy-handed approach protects kids. But youth pouch use in the US remains very low—about 1.5 percent of high-school students according to the latest National Youth Tobacco Survey—while nearly 30 million American adults still smoke. Denying safer products to millions of addicted adults because a tiny fraction of teens might experiment is the opposite of public-health logic.

There’s a better path. The FDA should base its decisions on science, not fear. If a product dramatically reduces exposure to harmful chemicals, meets strict packaging and marketing standards, and enforces Tobacco 21 age verification, it should be allowed on the market. Population-level effects can be monitored afterward through real-world data on switching and youth use. That’s how drug and vaccine regulation already works.

Sweden’s evidence shows the results of a pragmatic approach: a near-smoke-free society achieved through consumer choice, not coercion. The FDA’s own approval of ZYN proves that such products can meet its legal standard for protecting public health. The next step is consistency—apply the same rules to everyone.

Combustion, not nicotine, is the killer. Until the FDA acts on that simple truth, it will keep protecting the cigarette industry it was supposed to regulate.

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoFrom Underdog to Top Broodmare

-

Business1 day ago

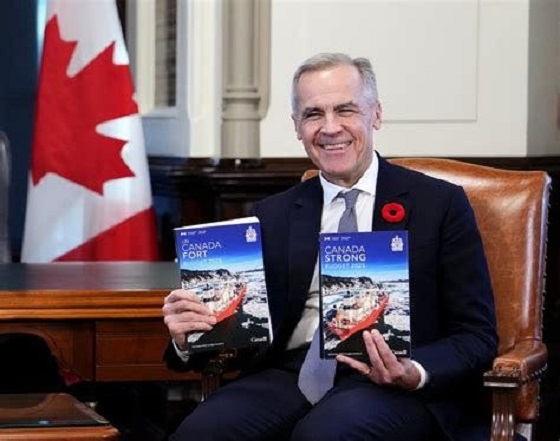

Business1 day agoMan overboard as HMCS Carney lists to the right

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoHigher carbon taxes in pipeline MOU are a bad deal for taxpayers

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoREAD IT HERE – Canada-Alberta Memorandum of Understanding – From the Prime Minister’s Office

-

COVID-192 days ago

COVID-192 days agoCanadian government seeking to destroy Freedom Convoy leader, taking Big Red from Chris Barber

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoMistakes and misinformation by experts cloud discussions on energy

-

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoIEA peak-oil reversal gives Alberta long-term leverage

-

National2 days ago

National2 days agoQuebec proposes to ban public prayer, harden laws against religious symbols