Business

Steel Subsidies Are The New Money Pit Burying Taxpayers

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

By Conrad Eder

The federal and Ontario governments’ $500 million loan to Algoma Steel exemplifies costly corporate welfare, with taxpayers bearing risks that private investors avoid, continuing a decades-long pattern of subsidies that distorts markets and burdens Canadians.

Governments call subsidies an economic strategy, but Canadians know they’re just another way to raid their pockets

Another day, another giveaway. This time, it’s Algoma Steel.

Despite the company’s market capitalization of roughly $500 million at the time, the governments of Canada and Ontario extended a loan equal to that amount—an extraordinary and objectively questionable move that isn’t just bad policy, but a sign that elected officials don’t know how to support businesses.

Officials justify the loan by claiming it will help Algoma refocus on its domestic market, lessening its reliance on the United States. Yet the fastest and most efficient way to execute such a strategy would involve doing so with private capital. Private markets allocate capital efficiently because investors directly bear the consequences of their decisions. Companies that cannot secure private funding typically lack a viable business model or face fundamental structural problems that subsidies will not solve.

Even if Algoma has a credible plan for pivoting its operations, the fact that taxpayers are shouldering risks private investors refuse to bear raises serious concerns. Canadians have a right to question whether this is a sound investment or just another costly political decision dressed up as economic strategy.

This isn’t the first time the company has leaned on public funds. Over the past three decades, Algoma has received more than $1.3 billion in government bailouts and subsidies, including $110 million for restructuring in 1992, $50 million in 2001, $60 million in 2015, $150 million in 2019, $420 million in 2021, and now $500 million in tariff-relief loans. That kind of prolonged public support makes it difficult to argue Algoma operates on a level playing field.

Proponents may argue that since Algoma continues to operate and provide employment, it proves government intervention works. But they ignore the enormous opportunity cost of these subsidies—costs largely hidden from public view. Every dollar spent propping up one company is a dollar that can’t fund other priorities, whether health care, education, infrastructure, or tax relief.

How will Ottawa and Queen’s Park cover their latest $500 million pledge? There are limited options. They may choose to forgo funding other priorities, borrow the money they just lent to cover other commitments, or monetize the debt by printing money or financing it through the central bank. In any case, Canadians are left worse off, whether by higher taxes, reduced services, or inflationary pressures. That’s the real cost of corporate subsidies, borne not by the companies that benefit, but by the public that pays.

But what if Algoma Steel faces further economic pressures, or its plans to refocus on domestic manufacturing fall through? Are we to expect that, having committed $500 million, the government will walk away? History suggests otherwise. More likely, officials will try to protect their investment regardless of the cost. It’s a slippery slope, one that often leads to even larger bailouts down the road.

Instead of selective corporate welfare, Canada should pursue policies that benefit all businesses: reducing regulatory burdens, lowering corporate tax rates, and eliminating trade barriers. These broad-based reforms create conditions where efficient companies thrive while inefficient ones face appropriate market discipline. The goal should be to make Canada more competitive overall, not just more generous to the few firms with political clout.

Adding insult to injury, this government’s simultaneous interventionism and protectionism places twice the burden on Canadians. First, taxpayers subsidize Algoma’s operations. Second, they pay premium prices for steel products thanks to federally imposed import tariffs introduced in recent years to shield domestic producers from lower-priced foreign steel. We are, in effect, subsidizing Algoma Steel to produce so that we can turn around and buy from them at higher prices than steel could be purchased from international competitors, if not for the tariffs. It’s a double hit to Canadians’ wallets.

Government officials invoke national security arguments to justify these measures, but in reality, they are engaging in the same economic protectionism they decry. During Trump’s first presidency, Canadian politicians rightly condemned similar American steel tariffs as protectionism disguised as security concerns. Now, Canadian officials are making identical arguments to defend their own policies.

While politicians warn about future threats to the country’s steel supply, it isn’t foreign governments restricting access. Ottawa has imposed its own import tariffs, limiting steel imports from abroad. The real barrier to securing steel supply isn’t an export ban. It’s Canada’s own trade policy.

Our own production capacity further weakens the government’s case. With companies like ArcelorMittal Dofasco and Stelco, Canada produces roughly 12.2 million metric tonnes of steel annually. That’s nearly enough to meet domestic demand. For everyday Canadians, this means alarms about steel shortages rings hollow.

This is not an endorsement of these other firms, as they have also received public funds, nearly $1 billion in recent years. In fact, Algoma might be disappointed not to have received more themselves. But it needn’t worry. With this government, another payout is likely just around the corner.

And once again, Canadians will foot the bill.

Conrad Eder is a policy analyst at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

Business

“Modernization,” They Call It: How Ottawa Redefined Fraud as Progress

When 41% of contracts break their promises, the scandal isn’t the system, it’s the spin that keeps it alive.

The House of Commons Standing Committee on Government Operations and Estimates (OGGO) held an in-depth hearing on Tuesday examining federal contracting integrity and the growing problem of “bait and switch” tactics identified in government procurements.

Appearing before the committee were Procurement Ombudsman Alexander Jeglic and his Senior Risk Advisor, Kelly Kilrea, who briefed Members of Parliament on the findings of their office’s 2025 special report titled “Bait and Switch in Federal Contracting.” The study detailed how some companies have won multimillion-dollar federal contracts by proposing highly qualified personnel, only to replace them after the award with less experienced or lower-cost workers.

Over more than two hours of questioning, MPs from all major parties probed whether this pattern amounted to fraud, negligence, or systemic mismanagement within Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC) and other departments. The Ombudsman told MPs that, while not every case involved deliberate deceit, the practice was widespread and harmful, undermining competition and eroding public trust in how taxpayer funds are spent.

“When a supplier wins a contract based on the credentials of specific experts, and those experts never perform the work, that raises serious integrity concerns,” Jeglic said. “Even without intent to deceive, the result is that the government may not receive the value it contracted for.”

The OGGO committee launched this study to scrutinize both the Procurement Ombudsman’s mandate and the findings of his most recent review into staffing substitutions under federal professional services contracts — a longstanding issue that resurfaced during the ArriveCAN controversy.

The Bait and Switch report, released in early 2025, examined 17 federal procurement files across several departments and agencies. The review revealed that in 41 percent of cases, the individuals proposed in the winning bids did not end up performing any of the contracted work. In many instances, these replacements occurred without proper documentation or departmental justification.

The problem first came to light through the Ombudsman’s separate investigation into the federal government’s ArriveCAN application, where the same pattern appeared on an even larger scale. In that review, Jeglic found that 76 percent of personnel proposed in ArriveCAN-related contracts never actually worked on the project, a statistic he described as “shockingly high.”

These findings prompted the Ombudsman to launch a broader system-wide review of whether “bait and switch” staffing practices had become entrenched in the government’s procurement culture. The 2025 report defined the practice explicitly as a scenario in which:

“A supplier secures a federal contract by proposing named individuals with particular qualifications or experience, but after contract award, substitutes them for others with lesser qualifications, without appropriate authorization or justification.”

The report stopped short of labeling the issue as fraud, since establishing intent is outside the Ombudsman’s statutory authority. However, it warned that the recurring pattern “poses a significant risk to fairness, transparency, and value for money in federal procurement.”

Jeglic told the committee that the tools to prevent this behaviour, such as contractual clauses requiring prior approval for resource changes, already existed but were not being consistently applied or enforced across departments.

As the hearing unfolded, the room divided neatly along partisan lines. Conservatives pushed hardest on accountability and possible cover-ups; Bloc Québécois MPs drilled into transparency and budget failures; and Liberal members defended the department’s response and pressed for moderation.

Each exchange revealed a very different interpretation of what the Ombudsman’s “bait and switch” report really meant.

Opposition MPs Hammer Procurement

The opposition benches came armed with pointed questions — and a tone of disbelief — as members of the Conservative Party and Bloc Québécois used Tuesday’s OGGO hearing to expose what they called a culture of impunity inside Ottawa’s contracting system.

The target wasn’t just the bureaucrats. It was the entire structure that lets contractors quietly swap qualified experts for cheaper, inexperienced staff after the ink is dry — and a federal apparatus that, even after years of warnings, still can’t stop it.

Conservatives: “They Know They Can Get Away With It”

Conservative MP Jeremy Patzer led the charge. He zeroed in on the heart of the bait-and-switch problem — companies winning bids with top-tier résumés, then cutting corners once the contract is secured.

“They know they can do it, and they know they can get away with it,” Patzer said. “Even if it’s not overt fraud, it’s systemic.”

Patzer pressed Ombudsman Alexander Jeglic on why, after years of oversight reports, nothing seems to change. He pointed to Recommendation 2 of the report, which urged the government to require that any replacement personnel match or exceed the original qualifications.

Public Services and Procurement Canada (PSPC), he noted, disagreed with even that.

“Why would they push back on something that simple?” he asked.

Jeglic’s answer: the department didn’t reject the idea, only where it should be implemented. It wanted the rule in contract templates, not in the overarching master agreement.

That didn’t satisfy the Conservatives. To them, the details were bureaucratic cover. The point was accountability — and the lack of it.

Patzer pressed further: could Jeglic even declare a finding of fraud if he saw one?

“No,” the Ombudsman admitted. “If we identified possible fraud, it would go to the RCMP.”

The Conservative benches shook their heads. In other words, the watchdog can bark but can’t bite.

Later in the hearing, Patzer returned, arguing that when nearly half of all reviewed contracts fail to deliver the promised experts, “something in the system isn’t working.”

“Surely some of these come close to outright fraud,” he said.

Jeglic didn’t disagree. “That would be fair,” he said, explaining that while his office couldn’t prove intent, the red flags were clear.

Tamara Jansen: “Canadians Expect Honesty and They’re Not Getting It”

Conservative Tamara Jansen picked up where Patzer left off — with sharper language. She called the entire practice “outrageous,” saying Canadians expect that when the government signs a multi-million-dollar contract, it actually gets the experts it was promised.

“This is bait and switch, plain and simple,” she said. “It violates the trust of taxpayers.”

Jansen accused departments of replacing real accountability with “policy workarounds,” referring to PSPC’s decision to stop evaluating individual qualifications altogether and instead score bids based on a company’s corporate experience.

“So now we don’t even check who’s doing the work?” she asked. “How is that improving anything?”

Jeglic explained that the change shifted procurement from a task-based model — where individual expertise is evaluated — to a solutions-based model, which focuses on the company’s proposed outcome.

That didn’t calm Jansen.

“Canadians have seen what happens when contractors get too creative,” she shot back. “We get ballooning costs, missed deadlines, no accountability — and taxpayers footing the bill.”

Her tone captured what much of the opposition was thinking: this wasn’t a one-off. It was the same pattern that produced ArriveCAN — confusion, waste, and no one taking responsibility.

Harb Gill: “Who Told You to Delete It?”

Liberal ministers weren’t the only ones on the defensive. Conservative MP Harb Gill went straight for what he called “the censorship angle.”

He cited The Globe and Mail’s reporting that government officials had asked Jeglic to remove an entire section from the Bait and Switch report — specifically the part outlining the policy’s negative impacts on small and medium-sized businesses.

“Who asked you to take it out?” Gill demanded.

Jeglic confirmed that the request came from the department itself, formally and in writing.

“They believed it was speculative and out of scope,” he said. “We disagreed.”

Gill asked whether the Ombudsman had ever faced that before.

“It’s not common,” Jeglic admitted. “Departments often suggest revisions — but full redactions are rare.”

He added that his office refused to comply and instead published both the department’s objection and his own rebuttal — verbatim — in the final report.

That exchange crystallized the opposition’s broader complaint: the bureaucracy doesn’t want scrutiny. When oversight gets too close to home, the instinct is to redact, not reform.

Bloc Québécois: “No Guarantee of Value for Money”

From the Bloc, Marie-Hélène Gaudreau framed the problem differently — as a question of public trust and fiscal responsibility.

“Can we guarantee to Quebecers and Canadians that the government is getting value for its money?” she asked in French.

Jeglic’s response was blunt:

“There’s no guarantee.”

Gaudreau pressed him on whether his small, underfunded office — operating on the same budget for 17 years — could properly monitor billions in federal spending. Jeglic said no, acknowledging “deep frustration” over his inability to expand his team despite repeatedly requesting funds.

“We have works in the queue that cannot be pursued,” he said. “Everyone understands the need — but I’ve never been successful.”

For the Bloc, that failure wasn’t just bureaucratic, it was political. Ottawa was starving its own oversight office while spending tens of billions through opaque contracts.

Liberals Defend the Swamp and Call It “Progress”

When the opposition came armed with outrage, the Liberals countered with spin — recasting what the Ombudsman called “bait and switch” as modernization.

Liberal MP Vince Gasparro downplayed the findings, calling the use of subcontractors and resource swaps “a common practice” that should continue. He even pivoted to talking about artificial intelligence, suggesting AI could “modernize” procurement — a remarkable leap of faith given Ottawa’s recent tech debacles.

Pauline Racheford went further, calling the report “thorough” and even saying she enjoyed reading it. She objected to the term bait and switch itself, insisting she didn’t see deception. Jeglic politely reminded her the term was deliberate — after years of ignored warnings, it was meant to grab attention.

Finally, Jenna Sudds moved to clean up the record. She asked if it was improper for departments to request edits to the Ombudsman’s reports. Jeglic confirmed it wasn’t — though he noted PSPC had tried to delete a full section, which his office refused.

Through it all, the Liberal message was consistent: there’s no scandal, just “evolution.”

Don’t call it bait and switch call it modernization.

Don’t call it failure call it progress.

Final Thoughts

So which is it? Are they incompetent or something worse?

Because let’s be honest: what we just watched wasn’t accountability, it was choreography. The watchdog says the federal government awarded contracts based on résumés that turned out to be fiction — and the Liberals’ response? Relax, it’s modernization.

They didn’t deny it happened. They just changed the vocabulary.

“Bait and switch” becomes “solutions-based contracting.”

Fraud becomes “flexibility.”

Failure becomes “progress.”

And when the Ombudsman exposes it, they call that a “balanced report.”

This isn’t evolution. It’s evasion, the bureaucratic art of saying everything while admitting nothing. Ottawa has spent two decades building a system where no one is ever responsible for anything, and they’re proud of it.

And that’s not the worst part because here’s a government that claims to be obsessed with “cutting waste,” with “efficiency,” with “respecting taxpayers’ money.” But when the one man in Ottawa actually capable of finding the waste sits in front of them and says, we can’t do our job because you won’t fund us, they nod, thank him politely, and move on.

Alexander Jeglic didn’t sound like a man crying for a bigger office or fancier title. He sounded like a man trapped inside a machine that’s designed not to work. He’s reviewing billions of dollars in federal contracts every year—contracts the government can’t seem to manage—and his entire budget hasn’t gone up since 2008. Seventeen years of inflation, and zero increase. That’s not oversight. That’s sabotage.

He told MPs his office uncovered that in 41 percent of contracts, the people taxpayers were told were doing the work never did. Think about that. Four out of ten contracts you pay for aren’t being delivered by the people who won them. That’s not a rounding error. That’s systemic rot. And the department responsible didn’t just shrug it off—they tried to delete it from the report.

They wanted the section removed. Formally. In writing. Because it made them look bad. Jeglic refused. He published their demand right there in the report. That’s what real accountability looks like.

And what did the government do? Nothing. No apology. No investigation. No increase in resources to stop it from happening again. Instead, they changed the rules so they no longer have to count it. They call it “solutions‑based contracting.” Translation: don’t measure outcomes, just redefine success until failure disappears.

If this were merely incompetence, you could fix it with new people. But it’s not. It’s a system that rewards itself for not knowing. They spend billions through opaque networks of consultants and subcontractors, and when someone tries to trace where the money went, the funding dries up.

This government spends more on communications staff than the Ombudsman’s entire office budget. They have teams of people paid to tell you how transparent they are, and the one office that could prove it is being starved to death.

So no—this isn’t about efficiency. It’s about control. They don’t want the waste found because the waste is the system. It’s how friends get paid, how failures get buried, and how no one is ever accountable.

You can call that whatever you like. But when the watchdog’s leash keeps getting tighter while the thieves run free, you stop wondering whether it’s incompetence. Because by that point, you already know the answer.

Alberta

Calgary’s High Property Taxes Run Counter to the ‘Alberta Advantage’

By David Hunt and Jeff Park

Of major cities, none compare to Calgary’s nearly 50 percent property tax burden increase between censuses.

Alberta once again leads the country in taking in more new residents than it loses to other provinces and territories. But if Canadians move to Calgary seeking greater affordability, are they in for a nasty surprise?

In light of declining home values and falling household incomes amidst rising property taxes, Calgary’s overall property tax burden has skyrocketed 47 percent between the last two national censuses, according to a new study by the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy.

Between 2016 and 2021 (the latest year of available data), Calgary’s property tax burden increased about twice as fast as second-place Saskatoon and three-and-a-half times faster than Vancouver.

The average Calgary homeowner paid $3,496 in property taxes at the last census, compared to $2,736 five years prior (using constant 2020 dollars; i.e., adjusting for inflation). By contrast, the average Edmonton homeowner paid $2,600 in 2021 compared to $2,384 in 2016 (in constant dollars). In other words, Calgary’s annual property tax bill rose three-and-a-half times more than Edmonton’s.

This is because Edmonton’s effective property tax rate remained relatively flat, while Calgary’s rose steeply. The effective rate is property tax as a share of the market value of a home. For Edmontonians, it rose from 0.56 percent to 0.62 percent—after rounding, a steady 0.6 percent across the two most recent censuses. For Calgarians? Falling home prices collided with rising taxes so that property taxes as a share of (market) home value rose from below 0.5 percent to nearly 0.7 percent.

Plug into the equation sliding household incomes, and we see that Calgary’s property tax burden ballooned nearly 50 percent between censuses.

This matters for at least three reasons. First, property tax is an essential source of revenue for municipalities across Canada. City councils set their property tax rate and the payments made by homeowners are the backbone of municipal finances.

Property taxes are also an essential source of revenue for schools. The province has historically required municipalities to directly transfer 33 percent of the total education budget via property taxes, but in the period under consideration that proportion fell (ultimately, to 28 percent).

Second, a home purchase is the largest expense most Canadians will ever make. Local taxes play a major role in how affordable life is from one city to another. When municipalities unexpectedly raise property taxes, it can push homeownership out of reach for many families. Thus, homeoowners (or prospective homeowners) naturally consider property tax rates and other local costs when choosing where to live and what home to buy.

And third, municipalities can fall into a vicious spiral if they’re not careful. When incomes decline and residential property values fall, as Calgary experienced during the period we studied, municipalities must either trim their budgets or increase property taxes. For many governments, it’s easier to raise taxes than cut spending.

But rising property tax burdens could lead to the city becoming a less desirable place to live. This could mean weaker residential property values, weaker population growth, and weaker growth in the number of residential properties. The municipality then again faces the choice of trimming budgets or raising taxes. And on and on it goes.

Cities fall into these downward spirals because they fall victim to a central planner’s bias. While $853 million for a new arena for the Calgary Flames or $11 million for Calgary Economic Development—how City Hall prefers to attract new business to Calgary—invite ribbon-cuttings, it’s the decisions about Calgary’s half a million private dwellings that really drive the city’s finances.

Yet, a virtuous spiral remains in reach. Municipalities tend to see the advantage of “affordable housing” when it’s centrally planned and taxpayer-funded but miss the easiest way to generate more affordable housing: simply charge city residents less—in taxes—for their housing.

When you reduce property taxes, you make housing more affordable to more people and make the city a more desirable place to live. This could mean stronger residential property values, stronger population growth, and stronger growth in the number of residential properties. Then, the municipality again faces a choice of making the city even more attractive by increasing services or further cutting taxes. And on and on it goes.

The economy is not a series of levers in the mayor’s office; it’s all of the million individual decisions that all of us, collectively, make. Calgary city council should reduce property taxes and leave more money for people to make the big decisions in life.

Jeff Park is a visiting fellow with the Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy and father of four who left Calgary for better affordability. David Hunt is the research director at the Calgary-based Aristotle Foundation for Public Policy. They are co-authors of the new study, Taxing our way to unaffordable housing: A brief comparison of municipal property taxes.

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoQuebecers want feds to focus on illegal gun smuggling not gun confiscation

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoEmission regulations harm Canadians in exchange for no environmental benefit

-

Courageous Discourse1 day ago

Courageous Discourse1 day agoNo Exit Wound – EITHER there was a very public “miracle” OR Charlie Kirk’s murder is not as it appears

-

Crime2 days ago

Crime2 days agoFrance stunned after thieves loot Louvre of Napoleon’s crown jewels

-

Carbon Tax3 hours ago

Carbon Tax3 hours agoBack Door Carbon Tax: Goal Of Climate Lawfare Movement To Drive Up Price Of Energy

-

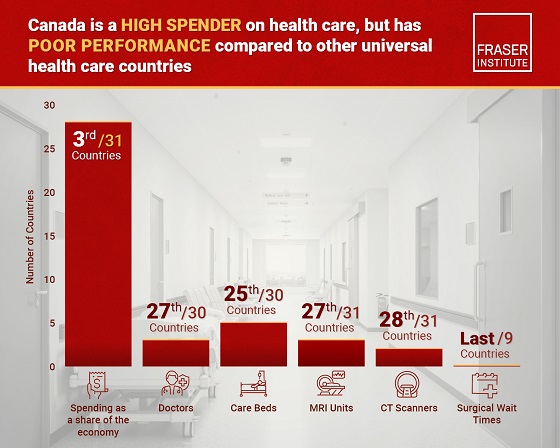

Business1 day ago

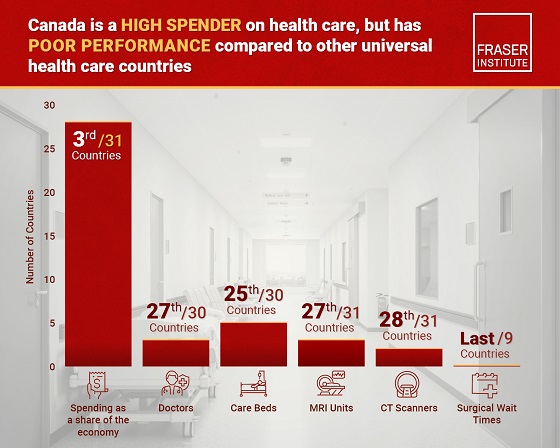

Business1 day agoCanada has fewer doctors, hospital beds, MRI machines—and longer wait times—than most other countries with universal health care

-

Automotive24 hours ago

Automotive24 hours agoParliament Forces Liberals to Release Stellantis Contracts After $15-Billion Gamble Blows Up In Taxpayer Faces

-

MAiD14 hours ago

MAiD14 hours agoDisabled Canadians increasingly under pressure to opt for euthanasia during routine doctor visits