Education

Schools should focus on falling math and reading skills—not environmental activism

From the Fraser Institute

In 2019 Toronto District School Board (TDSB) trustees passed a “climate emergency” resolution and promised to develop a climate action plan. Not only does the TDSB now have an entire department in their central office focused on this goal, but it also publishes an annual climate action report.

Imagine you were to ask a random group of Canadian parents to describe the primary mission of schools. Most parents would say something along the lines of ensuring that all students learn basic academic skills such as reading, writing and mathematics.

Fewer parents are likely to say that schools should focus on reducing their environmental footprints, push students to engage in environmental activism, or lobby for Canada to meet the 2016 Paris Agreement’s emission-reduction targets.

And yet, plenty of school boards across Canada are doing exactly that. For example, the Seven Oaks School Division in Winnipeg is currently conducting a comprehensive audit of its environmental footprint and intends to develop a climate action plan to reduce its footprint. Not only does Seven Oaks have a senior administrator assigned to this responsibility, but each of its 28 schools has a designated climate action leader.

Other school boards have gone even further. In 2019 Toronto District School Board (TDSB) trustees passed a “climate emergency” resolution and promised to develop a climate action plan. Not only does the TDSB now have an entire department in their central office focused on this goal, but it also publishes an annual climate action report. The most recent report is 58 pages long and covers everything from promoting electric school buses to encouraging schools to gain EcoSchools certification.

Not to be outdone, the Vancouver School District (VSD) recently published its Environmental Sustainability Plan, which highlights the many green initiatives in its schools. This plan states that the VSD should be the “greenest, most sustainable school district in North America.”

Some trustees want to go even further. Earlier this year, the British Columbia School Trustees Association released its Climate Action Working Group report that calls on all B.C. school districts to “prioritize climate change mitigation and adopt sustainable, impactful strategies.” It also says that taking climate action must be a “core part” of school board governance in every one of these districts.

Apparently, many trustees and school board administrators think that engaging in climate action is more important than providing students with a solid academic education. This is an unfortunate example of misplaced priorities.

There’s an old saying that when everything is a priority, nothing is a priority. Organizations have finite resources and can only do a limited number of things. When schools focus on carbon footprint audits, climate action plans and EcoSchools certification, they invariably spend less time on the nuts and bolts of academic instruction.

This might be less of a concern if the academic basics were already understood by students. But they aren’t. According to the most recent data from the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), the math skills of Ontario students declined by the equivalent of nearly two grade levels over the last 20 years while reading skills went down by about half a grade level. The downward trajectory was even sharper in B.C., with a more than two grade level decline in math skills and a full grade level decline in reading skills.

If any school board wants to declare an emergency, it should declare an academic emergency and then take concrete steps to rectify it. The core mandate of school boards must be the education of their students.

For starters, school boards should promote instructional methods that improve student academic achievement. This includes using phonics to teach reading, requiring all students to memorize basic math facts such as the times table, and encouraging teachers to immerse students in a knowledge-rich learning environment.

School boards should also crack down on student violence and enforce strict behaviour codes. Instead of kicking police officers out of schools for ideological reasons, school boards should establish productive partnerships with the police. No significant learning will take place in a school where students and teachers are unsafe.

Obviously, there’s nothing wrong with school boards ensuring that their buildings are energy efficient or teachers encouraging students to take care of the environment. The problem arises when trustees, administrators and teachers lose sight of their primary mission. In the end, schools should focus on academics, not environmental activism.

Alberta

Schools should go back to basics to mitigate effects of AI

From the Fraser Institute

Odds are, you can’t tell whether this sentence was written by AI. Schools across Canada face the same problem. And happily, some are finding simple solutions.

Manitoba’s Division Scolaire Franco-Manitobaine recently issued new guidelines for teachers, to only assign optional homework and reading in grades Kindergarten to six, and limit homework in grades seven to 12. The reason? The proliferation of generative artificial intelligence (AI) chatbots such as ChatGPT make it very difficult for teachers, juggling a heavy workload, to discern genuine student work from AI-generated text. In fact, according to Division superintendent Alain Laberge, “Most of the [after-school assignment] submissions, we find, are coming from AI, to be quite honest.”

This problem isn’t limited to Manitoba, of course.

Two provincial doors down, in Alberta, new data analysis revealed that high school report card grades are rising while scores on provincewide assessments are not—particularly since 2022, the year ChatGPT was released. Report cards account for take-home work, while standardized tests are written in person, in the presence of teaching staff.

Specifically, from 2016 to 2019, the average standardized test score in Alberta across a range of subjects was 64 while the report card grade was 73.3—or 9.3 percentage points higher). From 2022 and 2024, the gap increased to 12.5 percentage points. (Data for 2020 and 2021 are unavailable due to COVID school closures.)

In lieu of take-home work, the Division Scolaire Franco-Manitobaine recommends nightly reading for students, which is a great idea. Having students read nightly doesn’t cost schools a dime but it’s strongly associated with improving academic outcomes.

According to a Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) analysis of 174,000 student scores across 32 countries, the connection between daily reading and literacy was “moderately strong and meaningful,” and reading engagement affects reading achievement more than the socioeconomic status, gender or family structure of students.

All of this points to an undeniable shift in education—that is, teachers are losing a once-valuable tool (homework) and shifting more work back into the classroom. And while new technologies will continue to change the education landscape in heretofore unknown ways, one time-tested winning strategy is to go back to basics.

And some of “the basics” have slipped rapidly away. Some college students in elite universities arrive on campus never having read an entire book. Many university professors bemoan the newfound inability of students to write essays or deconstruct basic story components. Canada’s average PISA scores—a test of 15-year-olds in math, reading and science—have plummeted. In math, student test scores have dropped 35 points—the PISA equivalent of nearly two years of lost learning—in the last two decades. In reading, students have fallen about one year behind while science scores dropped moderately.

The decline in Canadian student achievement predates the widespread access of generative AI, but AI complicates the problem. Again, the solution needn’t be costly or complicated. There’s a reason why many tech CEOs famously send their children to screen-free schools. If technology is too tempting, in or outside of class, students should write with a pencil and paper. If ChatGPT is too hard to detect (and we know it is, because even AI often can’t accurately detect AI), in-class essays and assignments make sense.

And crucially, standardized tests provide the most reliable equitable measure of student progress, and if properly monitored, they’re AI-proof. Yet standardized testing is on the wane in Canada, thanks to long-standing attacks from teacher unions and other opponents, and despite broad support from parents. Now more than ever, parents and educators require reliable data to access the ability of students. Standardized testing varies widely among the provinces, but parents in every province should demand a strong standardized testing regime.

AI may be here to stay and it may play a large role in the future of education. But if schools deprive students of the ability to read books, structure clear sentences, correspond organically with other humans and complete their own work, they will do students no favours. The best way to ensure kids are “future ready”—to borrow a phrase oft-used to justify seesawing educational tech trends—is to school them in the basics.

Business

Why Does Canada “Lead” the World in Funding Racist Indoctrination?

-

Digital ID10 hours ago

Digital ID10 hours agoCanada releases new digital ID app for personal documents despite privacy concerns

-

Business21 hours ago

Business21 hours agoMajor tax changes in 2026: Report

-

Censorship Industrial Complex19 hours ago

Censorship Industrial Complex19 hours agoDeath by a thousand clicks – government censorship of Canada’s internet

-

Energy10 hours ago

Energy10 hours agoCanada’s sudden rediscovery of energy ambition has been greeted with a familiar charge: hypocrisy

-

Alberta22 hours ago

Alberta22 hours agoSchools should go back to basics to mitigate effects of AI

-

Daily Caller21 hours ago

Daily Caller21 hours agoChinese Billionaire Tried To Build US-Born Baby Empire As Overseas Elites Turn To American Surrogates

-

International19 hours ago

International19 hours agoRussia Now Open To Ukraine Joining EU, Officials Briefed On Peace Deal Say

-

Bruce Dowbiggin10 hours ago

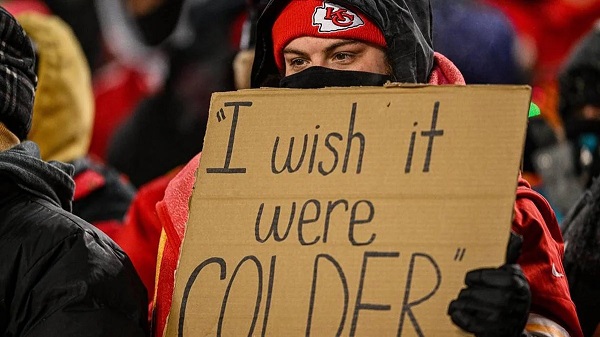

Bruce Dowbiggin10 hours agoNFL Ice Bowls Turn Down The Thermostat on Climate Change Hysteria