Fraser Institute

Ottawa’s health-care deal cements failed status quo in Canada

From the Fraser Institute

By Mackenzie Moir and Jake Fuss

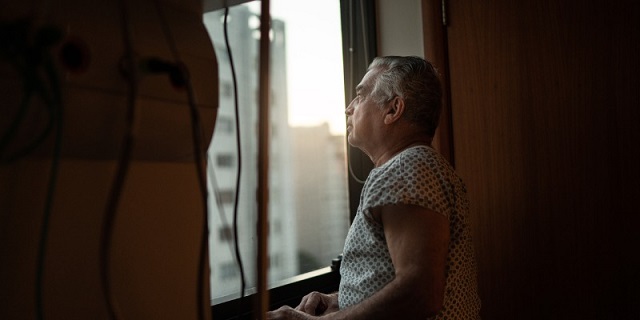

Canada will reach a projected $244.1 billion in 2023, which translates to $6,205 per person—nearly double the level of per-person spending (inflation-adjusted) three decades ago. And yet, last year Canadians endured the longest median wait time (27.7 weeks) ever recorded for non-emergency surgery.

Last week, as part of Ottawa’s promised $46 billion in additional health-care spending, the Trudeau government agreed to increase Quebec’s share of federal health-care dollars by $900 million annually. Quebec was the last province to reach an agreement with Ottawa before the March 31 deadline. With the closure of this agreement, Canadian taxpayers are on the hook for more health-care spending than ever before. For the same old broken health-care system.

Of course, it ultimately doesn’t matter whether the $46 billion originates from Ottawa or the provinces. In the end, Canadian taxpayers foot the bill. And what do we get in return for our health-care dollars?

In 2021, the latest year of comparable data, Canada’s total health-care spending (as a percentage of the economy) was the highest among 29 other comparable countries with universal health care (after adjusting for differences in population age). This isn’t a new development. Canada has a long history of having one of most expensive systems among high-income universal health-care countries.

Despite this, according to the latest comparable data, Canada ranks among the poorest performing universal health-care countries in key areas such as the number of physicians, hospital beds and diagnostic technology (e.g. MRI machines). Further, according to the Commonwealth Fund, in 2020 Canada ranked dead last on timely access to specialist consultations and non-emergency surgery.

Meanwhile, public health-care spending in Canada will reach a projected $244.1 billion in 2023, which translates to $6,205 per person—nearly double the level of per-person spending (inflation-adjusted) three decades ago. And yet, last year Canadians endured the longest median wait time (27.7 weeks) ever recorded for non-emergency surgery.

In short, Canada’s health-care system is in shambles, but the answer does not lie in simply throwing more money in its general direction. Federal politicians should instead look to the example of welfare reform during the Chrétien era in the 1990s. Those reforms, which reduced federal transfers to provinces and eliminated most of the “strings” attached to federal funding, resulted in increased provincial autonomy, greater policy experimentation, fewer Canadians needing welfare and savings for the federal government (i.e. taxpayers).

This is the opposite of today’s approach to health care, where the existing vehicle for federal funding (the Canada Health Transfer) is connected to the Canada Health Act (CHA), which prevents provincial governments from innovating and experimenting in health care by threatening financial penalties for non-compliance with often vaguely defined federal preferences. The result is a stalemate that satisfies no one and ensures that Canada’s policies remain at odds with the policies of our better-performing universal health-care peers.

While new federal dollars for health care are undoubtedly appealing to premiers, they will not improve the state of health care for Canadians. Until our federal politicians have the courage to reform the CHA and follow the example of 1990s welfare reform to improve outcomes, our health-care system’s unacceptable status quo will continue.

Authors:

Business

Fuelled by federalism—America’s economically freest states come out on top

From the Fraser Institute

Do economic rivalries between Texas and California or New York and Florida feel like yet another sign that America has become hopelessly divided? There’s a bright side to their disagreements, and a new ranking of economic freedom across the states helps explain why.

As a popular bumper sticker among economists proclaims: “I heart federalism (for the natural experiments).” In a federal system, states have wide latitude to set priorities and to choose their own strategies to achieve them. It’s messy, but informative.

New York and California, along with other states like New Mexico, have long pursued a government-centric approach to economic policy. They tax a lot. They spend a lot. Their governments employ a large fraction of the workforce and set a high minimum wage.

They aren’t socialist by any means; most property is still in private hands. Consumers, workers and businesses still make most of their own decisions. But these states control more resources than other states do through taxes and regulation, so their governments play a larger role in economic life.

At the other end of the spectrum, New Hampshire, Tennessee, Florida and South Dakota allow citizens to make more of their own economic choices, keep more of their own money, and set more of their own terms of trade and work.

They aren’t free-market utopias; they impose plenty of regulatory burdens. But they are economically freer than other states.

These two groups have, in other words, been experimenting with different approaches to economic policy. Does one approach lead to higher incomes or faster growth? Greater economic equality or more upward mobility? What about other aspects of a good society like tolerance, generosity, or life satisfaction?

For two decades now, we’ve had a handy tool to assess these questions: The Fraser Institute’s annual “Economic Freedom of North America” index uses 10 variables in three broad areas—government spending, taxation, and labor regulation—to assess the degree of economic freedom in each of the 50 states and the territory of Puerto Rico, as well as in Canadian provinces and Mexican states.

It’s an objective measurement that allows economists to take stock of federalism’s natural experiments. Independent scholars have done just that, having now conducted over 250 studies using the index. With careful statistical analyses that control for the important differences among states—possibly confounding factors such as geography, climate, and historical development—the vast majority of these studies associate greater economic freedom with greater prosperity.

In fact, freedom’s payoffs are astounding.

States with high and increasing levels of economic freedom tend to see higher incomes, more entrepreneurial activity and more net in-migration. Their people tend to experience greater income mobility, and more income growth at both the top and bottom of the income distribution. They have less poverty, less homelessness and lower levels of food insecurity. People there even seem to be more philanthropic, more tolerant and more satisfied with their lives.

New Hampshire, Tennessee, and South Dakota topped the latest edition of the report while Puerto Rico, New Mexico, and New York rounded out the bottom. New Mexico displaced New York as the least economically free state in the union for the first time in 20 years, but it had always been near the bottom.

The bigger stories are the major movers. The last 10 years’ worth of available data show South Carolina, Ohio, Wisconsin, Idaho, Iowa and Utah moving up at least 10 places. Arizona, Virginia, Nebraska, and Maryland have all slid down 10 spots.

Over that same decade, those states that were among the freest 25 per cent on average saw their populations grow nearly 18 times faster than those in the bottom 25 per cent. Statewide personal income grew nine times as fast.

Economic freedom isn’t a panacea. Nor is it the only thing that matters. Geography, culture, and even luck can influence a state’s prosperity. But while policymakers can’t move mountains or rewrite cultures, they can look at the data, heed the lessons of our federalist experiment, and permit their citizens more economic freedom.

Business

Brutal economic numbers need more course corrections from Ottawa

From the Fraser Institute

By Matthew Lau

Canada’s lagging productivity growth has been widely discussed, especially after Bank of Canada senior deputy governor Carolyn Rogers last year declared it “an emergency” and said “it’s time to break the glass.” The federal Liberal government, now entering its eleventh year in office, admitted in its recent budget that “productivity remains weak, limiting wage gains for workers.”

Numerous recent reports show just how weak Canada’s productivity has been. A recent study published by the Fraser Institute shows that since 2001, labour productivity has increased only 16.5 per cent in Canada vs. 54.7 per cent in the United States, with our underperformance especially notable after 2017. Weak business investment is a primary reason for Canada’s continued poor economic outcomes.

A recent McKinsey study provides worrying details about how the productivity crisis pervades almost all sectors of the economy. Relative to the U.S., our labour productivity underperforms in: mining, quarrying, and oil and gas extraction; construction; manufacturing; transportation and warehousing; retail trade; professional, scientific, and technical services; real estate and rental leasing; wholesale trade; finance and insurance; information and cultural industries; accommodation and food services; utilities; arts, entertainment and recreation; and administrative and support, waste management and remediation services.

Canada has relatively higher labour productivity in just one area: agriculture, forestry, fishing and hunting. To make matters worse, in most areas where Canada’s labour productivity is less than American, McKinsey found we had fallen further behind from 2014 to 2023. In addition to doing poorly, Canada is trending in the wrong direction.

Broadening the comparison to include other OECD countries does not make the picture any rosier—Canada “is growing more slowly and from a lower base,” as McKinsey put it. This underperformance relative to other countries shows Canada’s economic productivity crisis is not the result of external factors but homemade.

The federal Liberals have done little to reverse our relative decline. The Carney government’s proposed increased spending on artificial intelligence (AI) may or may not help. But its first budget missed a clear opportunity to implement tax reform and cuts. As analyses from the Fraser Institute, University of Calgary, C.D. Howe Institute, TD Economics and others have argued, fixing Canada’s uncompetitive tax regime would help lift productivity.

Regulatory expansion has also driven Canada’s relative economic decline but the federal budget did not reduce the red tape burden. Instead, the Carney government empowered cabinet to decide which large natural resource and infrastructure projects are in the “national interest”—meaning that instead of predictable transparent rules, businesses must answer to the whims of politicians.

The government has also left in place many of its Trudeau-era environmental regulations, which have helped push pipeline investors away for years. It is encouraging that a new “memorandum of understanding” between Ottawa and Alberta may pave the way for a new oil pipeline. A memorandum of undertaking would have been better.

Although the government paused its phased-in ban on conventionally-powered vehicle sales in the face of heavy tariff-related headwinds to Canada’s automobile sector, it still insists that all new light-duty vehicle sales by 2035 must be electric. Liberal MPs on the House of Commons Industry Committee recently voted against a Conservative motion calling for repeal of the EV mandate. Meanwhile, Canadian consumers are voting with their wallets. In September, only 10.2 per cent of new motor vehicle sales were “zero-emission,” an ominous18.2 per cent decline from last year.

If the Carney government continues down its current path, it will only make productivity and consumer welfare worse. It should change course to reverse Canada’s economic underperformance and help give living standards a much-needed boost.

-

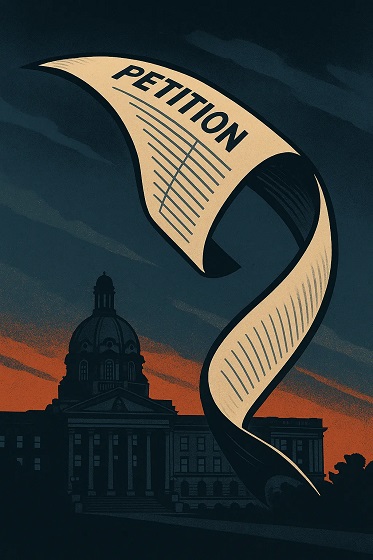

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoThe Recall Trap: 21 Alberta MLA’s face recall petitions

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoTyler Robinson shows no remorse in first court appearance for Kirk assassination

-

Energy1 day ago

Energy1 day agoCanada’s future prosperity runs through the northwest coast

-

illegal immigration1 day ago

illegal immigration1 day agoUS Notes 2.5 million illegals out and counting

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoThe world is no longer buying a transition to “something else” without defining what that is

-

2025 Federal Election2 days ago

2025 Federal Election2 days agoToo Close for Comfort: Carney Floor Crosser Comes From a Riding Tainted by PRC Interference

-

Daily Caller19 hours ago

Daily Caller19 hours ago‘There Will Be Very Serious Retaliation’: Two American Servicemen, Interpreter Killed In Syrian Attack

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoHigh-speed rail between Toronto and Quebec City a costly boondoggle for Canadian taxpayers