Brownstone Institute

Is the Overton Window Real, Imagined, or Constructed?

From the Brownstone Institute

BY

Ideas move from Unthinkable to Radical to Acceptable to Sensible to Popular to become Policy.

The concept of the Overton window caught on in professional culture, particularly those seeking to nudge public opinion, because it taps into a certain sense that we all know is there. There are things you can say and things you cannot say, not because there are speech controls (though there are) but because holding certain views makes you anathema and dismissable. This leads to less influence and effectiveness.

The Overton window is a way of mapping sayable opinions. The goal of advocacy is to stay within the window while moving it just ever so much. For example, if you are writing about monetary policy, you should say that the Fed should not immediately reduce rates for fear of igniting inflation. You can really think that the Fed should be abolished but saying that is inconsistent with the demands of polite society.

That’s only one example of a million.

To notice and comply with the Overton window is not the same as merely favoring incremental change over dramatic reform. There is not and should never be an issue with marginal change. That’s not what is at stake.

To be aware of the Overton window, and fit within it, means to curate your own advocacy. You should do so in a way that is designed to comply with a structure of opinion that is pre-existing as a kind of template we are all given. It means to craft a strategy specifically designed to game the system, which is said to operate according to acceptable and unacceptable opinionizing.

In every area of social, economic, and political life, we find a form of compliance with strategic considerations seemingly dictated by this Window. There is no sense in spouting off opinions that offend or trigger people because they will just dismiss you as not credible. But if you keep your eye on the Window – as if you can know it, see it, manage it – you might succeed in expanding it a bit here and there and thereby achieve your goals eventually.

The mission here is always to let considerations of strategy run alongside – perhaps even ultimately prevail in the short run – over issues of principle and truth, all in the interest of being not merely right but also effective. Everyone in the business of affecting public opinion does this, all in compliance with the perception of the existence of this Window.

Tellingly, the whole idea grows out of think tank culture, which puts a premium on effectiveness and metrics as a means of institutional funding. The concept was named for Joseph Overton, who worked at the Mackinac Center for Public Policy in Michigan. He found that it was useless in his work to advocate for positions that he could not recruit politicians to say from the legislative floor or on the campaign trail. By crafting policy ideas that fit within the prevailing media and political culture, however, he saw some successes about which he and his team could brag to the donor base.

This experience led him to a more general theory that was later codified by his colleague Joseph Lehman, and then elaborated upon by Joshua Treviño, who postulated degrees of acceptability. Ideas move from Unthinkable to Radical to Acceptable to Sensible to Popular to become Policy. A wise intellectual shepherd will manage this transition carefully from one stage to the next until victory and then take on a new issue.

The core intuition here is rather obvious. It probably achieves little in life to go around screaming some radical slogan about what all politicians should do if there is no practical means to achieve it and zero chance of it happening. But writing well-thought-out position papers with citations backed by large books by Ivy League authors and pushing for changes on the margin that keep politicians out of trouble with the media might move the Window slightly and eventually enough to make a difference.

Beyond that example, which surely does tap into some evidence in this or that case, how true is this analysis?

First, the theory of the Overton window presumes a smooth connection between public opinion and political outcomes. During most of my life, that seemed to be the case or, at least, we imagined it to be the case. Today this is gravely in question. Politicians do things daily and hourly that are opposed by their constituents – fund foreign aid and wars for example – but they do it anyway due to well-organized pressure groups that operate outside public awareness. That’s true many times over with the administrative and deep layers of the state.

In most countries, states and elites that run them operate without the consent of the governed. No one likes the surveillance and censorial state but they are growing regardless, and nothing about shifts in public opinion seem to make any difference. It’s surely true that there comes a point when state managers pull back on their schemes for fear of public backlash but when that happens or where, or when and how, wholly depends on the circumstances of time and place.

Second, the Overton window presumes there is something organic about the way the Window is shaped and moves. That is probably not entirely true either. Revelations of our own time show just how involved are major state actors in media and tech, even to the point of dictating the structure and parameters of opinions held in the public, all in the interest of controlling the culture of belief in the population.

I had read Manufacturing Consent (Noam Chomsky and Edward Herman; full text here) when it came out in 1988 and found it compelling. It was entirely believable that deep ruling class interests were more involved than we know about what we are supposed to think about foreign-policy matters and national emergencies, and, further, entirely plausible that major media outlets would reflect these views as a matter of seeking to fit in and ride the wave of change.

What I had not understood was just how far-reaching this effort to manufacture consent is in real life. What illustrates this perfectly has been media and censorship over the pandemic years in which nearly all official channels of opinion have very strictly reflected and enforced the cranky views of a tiny elite. Honestly, how many actual people in the US were behind the lockdowns policy in terms of theory and action? Probably fewer than 1,000. Probably closer to 100.

But thanks to the work of the Censorship Industrial Complex, an industry built of dozens of agencies and thousands of third-party cutouts including universities, we were led to believe that lockdowns and closures were just the way things are done. Vast amounts of the propaganda we endured was top down and wholly manufactured.

Third, the lockdown experience demonstrates that there is nothing necessarily slow and evolutionary about the movement of the Window. In February 2020, mainstream public health was warning against travel restrictions, quarantines, business closures, and the stigmatization of the sick. A mere 30 days later, all these policies became acceptable and even mandatory belief. Not even Orwell imagined such a dramatic and sudden shift was possible!

The Window didn’t just move. It dramatically shifted from one side of the room to the other, with all the top players against saying the right thing at the right time, and then finding themselves in the awkward position of having to publicly contradict what they had said only weeks earlier. The excuse was that “the science changed” but that is completely untrue and an obvious cover for what was really just a craven attempt to chase what the powerful were saying and doing.

It was the same with the vaccine, which major media voices opposed so long as Trump was president and then favored once the election was declared for Biden. Are we really supposed to believe that this massive switch came about because of some mystical window shift or does the change have a more direct explanation?

Fourth, the entire model is wildly presumptuous. It is built by intuition, not data, of course. And it presumes that we can know the parameters of its existence and manage how it is gradually manipulated over time. None of this is true. In the end, an agenda based on acting on this supposed Window involves deferring to the intuitions of some manager who decides that this or that statement or agenda is “good optics” or “bad optics,” to deploy the fashionable language of our time.

The right response to all such claims is: you don’t know that. You are only pretending to know but you don’t actually know. What your seemingly perfect discernment of strategy is really about concerns your own personal taste for the fight, for controversy, for argument, and your willingness to stand up publicly for a principle you believe will very likely run counter to elite priorities. That’s perfectly fine, but don’t mask your taste for public engagement in the garb of fake management theory.

It’s precisely for this reason that so many intellectuals and institutions stayed completely silent during lockdowns when everyone was being treated so brutally by public health. Many people knew the truth – that everyone would get this bug, most would shake it off just fine, and then it would become endemic – but were simply afraid to say it. Cite the Overton window all you want but what is really at issue is one’s willingness to exercise moral courage.

The relationship between public opinion, cultural feeling, and state policy has always been complex, opaque, and beyond the capacity of empirical methods to model. It’s for this reason that there is such a vast literature on social change.

We live in times in which most of what we thought we knew about the strategies for social and political change have been blown up. That’s simply because the normal world we knew only five years ago – or thought we knew – no longer exists. Everything is broken, including whatever imaginings we had about the existence of this Overton window.

What to do about it? I would suggest a simple answer. Forget the model, which might be completely misconstrued in any case. Just say what is true, with sincerity, without malice, without convoluted hopes of manipulating others. It’s a time for truth, which earns trust. Only that will blow the window wide open and finally demolish it forever.

Brownstone Institute

The Unmasking of Vaccine Science

From the Brownstone Institute

By

I recently purchased Aaron Siri’s new book Vaccines, Amen. As I flipped though the pages, I noticed a section devoted to his now-famous deposition of Dr Stanley Plotkin, the “godfather” of vaccines.

I’d seen viral clips circulating on social media, but I had never taken the time to read the full transcript — until now.

Siri’s interrogation was methodical and unflinching…a masterclass in extracting uncomfortable truths.

A Legal Showdown

In January 2018, Dr Stanley Plotkin, a towering figure in immunology and co-developer of the rubella vaccine, was deposed under oath in Pennsylvania by attorney Aaron Siri.

The case stemmed from a custody dispute in Michigan, where divorced parents disagreed over whether their daughter should be vaccinated. Plotkin had agreed to testify in support of vaccination on behalf of the father.

What followed over the next nine hours, captured in a 400-page transcript, was extraordinary.

Plotkin’s testimony revealed ethical blind spots, scientific hubris, and a troubling indifference to vaccine safety data.

He mocked religious objectors, defended experiments on mentally disabled children, and dismissed glaring weaknesses in vaccine surveillance systems.

A System Built on Conflicts

From the outset, Plotkin admitted to a web of industry entanglements.

He confirmed receiving payments from Merck, Sanofi, GSK, Pfizer, and several biotech firms. These were not occasional consultancies but long-standing financial relationships with the very manufacturers of the vaccines he promoted.

Plotkin appeared taken aback when Siri questioned his financial windfall from royalties on products like RotaTeq, and expressed surprise at the “tone” of the deposition.

Siri pressed on: “You didn’t anticipate that your financial dealings with those companies would be relevant?”

Plotkin replied: “I guess, no, I did not perceive that that was relevant to my opinion as to whether a child should receive vaccines.”

The man entrusted with shaping national vaccine policy had a direct financial stake in its expansion, yet he brushed it aside as irrelevant.

Contempt for Religious Dissent

Siri questioned Plotkin on his past statements, including one in which he described vaccine critics as “religious zealots who believe that the will of God includes death and disease.”

Siri asked whether he stood by that statement. Plotkin replied emphatically, “I absolutely do.”

Plotkin was not interested in ethical pluralism or accommodating divergent moral frameworks. For him, public health was a war, and religious objectors were the enemy.

He also admitted to using human foetal cells in vaccine production — specifically WI-38, a cell line derived from an aborted foetus at three months’ gestation.

Siri asked if Plotkin had authored papers involving dozens of abortions for tissue collection. Plotkin shrugged: “I don’t remember the exact number…but quite a few.”

Plotkin regarded this as a scientific necessity, though for many people — including Catholics and Orthodox Jews — it remains a profound moral concern.

Rather than acknowledging such sensitivities, Plotkin dismissed them outright, rejecting the idea that faith-based values should influence public health policy.

That kind of absolutism, where scientific aims override moral boundaries, has since drawn criticism from ethicists and public health leaders alike.

As NIH director Jay Bhattacharya later observed during his 2025 Senate confirmation hearing, such absolutism erodes trust.

“In public health, we need to make sure the products of science are ethically acceptable to everybody,” he said. “Having alternatives that are not ethically conflicted with foetal cell lines is not just an ethical issue — it’s a public health issue.”

Safety Assumed, Not Proven

When the discussion turned to safety, Siri asked, “Are you aware of any study that compares vaccinated children to completely unvaccinated children?”

Plotkin replied that he was “not aware of well-controlled studies.”

Asked why no placebo-controlled trials had been conducted on routine childhood vaccines such as hepatitis B, Plotkin said such trials would be “ethically difficult.”

That rationale, Siri noted, creates a scientific blind spot. If trials are deemed too unethical to conduct, then gold-standard safety data — the kind required for other pharmaceuticals — simply do not exist for the full childhood vaccine schedule.

Siri pointed to one example: Merck’s hepatitis B vaccine, administered to newborns. The company had only monitored participants for adverse events for five days after injection.

Plotkin didn’t dispute it. “Five days is certainly short for follow-up,” he admitted, but claimed that “most serious events” would occur within that time frame.

Siri challenged the idea that such a narrow window could capture meaningful safety data — especially when autoimmune or neurodevelopmental effects could take weeks or months to emerge.

Siri pushed on. He asked Plotkin if the DTaP and Tdap vaccines — for diphtheria, tetanus and pertussis — could cause autism.

“I feel confident they do not,” Plotkin replied.

But when shown the Institute of Medicine’s 2011 report, which found the evidence “inadequate to accept or reject” a causal link between DTaP and autism, Plotkin countered, “Yes, but the point is that there were no studies showing that it does cause autism.”

In that moment, Plotkin embraced a fallacy: treating the absence of evidence as evidence of absence.

“You’re making assumptions, Dr Plotkin,” Siri challenged. “It would be a bit premature to make the unequivocal, sweeping statement that vaccines do not cause autism, correct?”

Plotkin relented. “As a scientist, I would say that I do not have evidence one way or the other.”

The MMR

The deposition also exposed the fragile foundations of the measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccine.

When Siri asked for evidence of randomised, placebo-controlled trials conducted before MMR’s licensing, Plotkin pushed back: “To say that it hasn’t been tested is absolute nonsense,” he said, claiming it had been studied “extensively.”

Pressed to cite a specific trial, Plotkin couldn’t name one. Instead, he gestured to his own 1,800-page textbook: “You can find them in this book, if you wish.”

Siri replied that he wanted an actual peer-reviewed study, not a reference to Plotkin’s own book. “So you’re not willing to provide them?” he asked. “You want us to just take your word for it?”

Plotkin became visibly frustrated.

Eventually, he conceded there wasn’t a single randomised, placebo-controlled trial. “I don’t remember there being a control group for the studies, I’m recalling,” he said.

The exchange foreshadowed a broader shift in public discourse, highlighting long-standing concerns that some combination vaccines were effectively grandfathered into the schedule without adequate safety testing.

In September this year, President Trump called for the MMR vaccine to be broken up into three separate injections.

The proposal echoed a view that Andrew Wakefield had voiced decades earlier — namely, that combining all three viruses into a single shot might pose greater risk than spacing them out.

Wakefield was vilified and struck from the medical register. But now, that same question — once branded as dangerous misinformation — is set to be re-examined by the CDC’s new vaccine advisory committee, chaired by Martin Kulldorff.

The Aluminium Adjuvant Blind Spot

Siri next turned to aluminium adjuvants — the immune-activating agents used in many childhood vaccines.

When asked whether studies had compared animals injected with aluminium to those given saline, Plotkin conceded that research on their safety was limited.

Siri pressed further, asking if aluminium injected into the body could travel to the brain. Plotkin replied, “I have not seen such studies, no, or not read such studies.”

When presented with a series of papers showing that aluminium can migrate to the brain, Plotkin admitted he had not studied the issue himself, acknowledging that there were experiments “suggesting that that is possible.”

Asked whether aluminium might disrupt neurological development in children, Plotkin stated, “I’m not aware that there is evidence that aluminum disrupts the developmental processes in susceptible children.”

Taken together, these exchanges revealed a striking gap in the evidence base.

Compounds such as aluminium hydroxide and aluminium phosphate have been injected into babies for decades, yet no rigorous studies have ever evaluated their neurotoxicity against an inert placebo.

This issue returned to the spotlight in September 2025, when President Trump pledged to remove aluminium from vaccines, and world-leading researcher Dr Christopher Exley renewed calls for its complete reassessment.

A Broken Safety Net

Siri then turned to the reliability of the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System (VAERS) — the primary mechanism for collecting reports of vaccine-related injuries in the United States.

Did Plotkin believe most adverse events were captured in this database?

“I think…probably most are reported,” he replied.

But Siri showed him a government-commissioned study by Harvard Pilgrim, which found that fewer than 1% of vaccine adverse events are reported to VAERS.

“Yes,” Plotkin said, backtracking. “I don’t really put much faith into the VAERS system…”

Yet this is the same database officials routinely cite to claim that “vaccines are safe.”

Ironically, Plotkin himself recently co-authored a provocative editorial in the New England Journal of Medicine, conceding that vaccine safety monitoring remains grossly “inadequate.”

Experimenting on the Vulnerable

Perhaps the most chilling part of the deposition concerned Plotkin’s history of human experimentation.

“Have you ever used orphans to study an experimental vaccine?” Siri asked.

“Yes,” Plotkin replied.

“Have you ever used the mentally handicapped to study an experimental vaccine?” Siri asked.

“I don’t recollect…I wouldn’t deny that I may have done so,” Plotkin replied.

Siri cited a study conducted by Plotkin in which he had administered experimental rubella vaccines to institutionalised children who were “mentally retarded.”

Plotkin stated flippantly, “Okay well, in that case…that’s what I did.”

There was no apology, no sign of ethical reflection — just matter-of-fact acceptance.

Siri wasn’t done.

He asked if Plotkin had argued that it was better to test on those “who are human in form but not in social potential” rather than on healthy children.

Plotkin admitted to writing it.

Siri established that Plotkin had also conducted vaccine research on the babies of imprisoned mothers, and on colonised African populations.

Plotkin appeared to suggest that the scientific value of such studies outweighed the ethical lapses—an attitude that many would interpret as the classic ‘ends justify the means’ rationale.

But that logic fails the most basic test of informed consent. Siri asked whether consent had been obtained in these cases.

“I don’t remember…but I assume it was,” Plotkin said.

Assume?

This was post-Nuremberg research. And the leading vaccine developer in America couldn’t say for sure whether he had properly informed the people he experimented on.

In any other field of medicine, such lapses would be disqualifying.

A Casual Dismissal of Parental Rights

Plotkin’s indifference to experimenting on disabled children didn’t stop there.

Siri asked whether someone who declined a vaccine due to concerns about missing safety data should be labelled “anti-vax.”

Plotkin replied, “If they refused to be vaccinated themselves or refused to have their children vaccinated, I would call them an anti-vaccination person, yes.”

Plotkin was less concerned about adults making that choice for themselves, but he had no tolerance for parents making those choices for their own children.

“The situation for children is quite different,” said Plotkin, “because one is making a decision for somebody else and also making a decision that has important implications for public health.”

In Plotkin’s view, the state held greater authority than parents over a child’s medical decisions — even when the science was uncertain.

The Enabling of Figures Like Plotkin

The Plotkin deposition stands as a case study in how conflicts of interest, ideology, and deference to authority have corroded the scientific foundations of public health.

Plotkin is no fringe figure. He is celebrated, honoured, and revered. Yet he promotes vaccines that have never undergone true placebo-controlled testing, shrugs off the failures of post-market surveillance, and admits to experimenting on vulnerable populations.

This is not conjecture or conspiracy — it is sworn testimony from the man who helped build the modern vaccine program.

Now, as Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. reopens long-dismissed questions about aluminium adjuvants and the absence of long-term safety studies, Plotkin’s once-untouchable legacy is beginning to fray.

Republished from the author’s Substack

Brownstone Institute

Bizarre Decisions about Nicotine Pouches Lead to the Wrong Products on Shelves

From the Brownstone Institute

A walk through a dozen convenience stores in Montgomery County, Pennsylvania, says a lot about how US nicotine policy actually works. Only about one in eight nicotine-pouch products for sale is legal. The rest are unauthorized—but they’re not all the same. Some are brightly branded, with uncertain ingredients, not approved by any Western regulator, and clearly aimed at impulse buyers. Others—like Sweden’s NOAT—are the opposite: muted, well-made, adult-oriented, and already approved for sale in Europe.

Yet in the United States, NOAT has been told to stop selling. In September 2025, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued the company a warning letter for offering nicotine pouches without marketing authorization. That might make sense if the products were dangerous, but they appear to be among the safest on the market: mild flavors, low nicotine levels, and recyclable paper packaging. In Europe, regulators consider them acceptable. In America, they’re banned. The decision looks, at best, strange—and possibly arbitrary.

What the Market Shows

My October 2025 audit was straightforward. I visited twelve stores and recorded every distinct pouch product visible for sale at the counter. If the item matched one of the twenty ZYN products that the FDA authorized in January, it was counted as legal. Everything else was counted as illegal.

Two of the stores told me they had recently received FDA letters and had already removed most illegal stock. The other ten stores were still dominated by unauthorized products—more than 93 percent of what was on display. Across all twelve locations, about 12 percent of products were legal ZYN, and about 88 percent were not.

The illegal share wasn’t uniform. Many of the unauthorized products were clearly high-nicotine imports with flashy names like Loop, Velo, and Zimo. These products may be fine, but some are probably high in contaminants, and a few often with very high nicotine levels. Others were subdued, plainly meant for adult users. NOAT was a good example of that second group: simple packaging, oat-based filler, restrained flavoring, and branding that makes no effort to look “cool.” It’s the kind of product any regulator serious about harm reduction would welcome.

Enforcement Works

To the FDA’s credit, enforcement does make a difference. The two stores that received official letters quickly pulled their illegal stock. That mirrors the agency’s broader efforts this year: new import alerts to detain unauthorized tobacco products at the border (see also Import Alert 98-06), and hundreds of warning letters to retailers, importers, and distributors.

But effective enforcement can’t solve a supply problem. The list of legal nicotine-pouch products is still extremely short—only a narrow range of ZYN items. Adults who want more variety, or stores that want to meet that demand, inevitably turn to gray-market suppliers. The more limited the legal catalog, the more the illegal market thrives.

Why the NOAT Decision Appears Bizarre

The FDA’s own actions make the situation hard to explain. In January 2025, it authorized twenty ZYN products after finding that they contained far fewer harmful chemicals than cigarettes and could help adult smokers switch. That was progress. But nine months later, the FDA has approved nothing else—while sending a warning letter to NOAT, arguably the least youth-oriented pouch line in the world.

The outcome is bad for legal sellers and public health. ZYN is legal; a handful of clearly risky, high-nicotine imports continue to circulate; and a mild, adult-market brand that meets European safety and labeling rules is banned. Officially, NOAT’s problem is procedural—it lacks a marketing order. But in practical terms, the FDA is punishing the very design choices it claims to value: simplicity, low appeal to minors, and clean ingredients.

This approach also ignores the differences in actual risk. Studies consistently show that nicotine pouches have far fewer toxins than cigarettes and far less variability than many vapes. The biggest pouch concerns are uneven nicotine levels and occasional traces of tobacco-specific nitrosamines, depending on manufacturing quality. The serious contamination issues—heavy metals and inconsistent dosage—belong mostly to disposable vapes, particularly the flood of unregulated imports from China. Treating all “unauthorized” products as equally bad blurs those distinctions and undermines proportional enforcement.

A Better Balance: Enforce Upstream, Widen the Legal Path

My small Montgomery County survey suggests a simple formula for improvement.

First, keep enforcement targeted and focused on suppliers, not just clerks. Warning letters clearly change behavior at the store level, but the biggest impact will come from auditing distributors and importers, and stopping bad shipments before they reach retail shelves.

Second, make compliance easy. A single-page list of authorized nicotine-pouch products—currently the twenty approved ZYN items—should be posted in every store and attached to distributor invoices. Point-of-sale systems can block barcodes for anything not on the list, and retailers could affirm, once a year, that they stock only approved items.

Third, widen the legal lane. The FDA launched a pilot program in September 2025 to speed review of new pouch applications. That program should spell out exactly what evidence is needed—chemical data, toxicology, nicotine release rates, and behavioral studies—and make timely decisions. If products like NOAT meet those standards, they should be authorized quickly. Legal competition among adult-oriented brands will crowd out the sketchy imports far faster than enforcement alone.

The Bottom Line

Enforcement matters, and the data show it works—where it happens. But the legal market is too narrow to protect consumers or encourage innovation. The current regime leaves a few ZYN products as lonely legal islands in a sea of gray-market pouches that range from sensible to reckless.

The FDA’s treatment of NOAT stands out as a case study in inconsistency: a quiet, adult-focused brand approved in Europe yet effectively banned in the US, while flashier and riskier options continue to slip through. That’s not a public-health victory; it’s a missed opportunity.

If the goal is to help adult smokers move to lower-risk products while keeping youth use low, the path forward is clear: enforce smartly, make compliance easy, and give good products a fair shot. Right now, we’re doing the first part well—but failing at the second and third. It’s time to fix that.

-

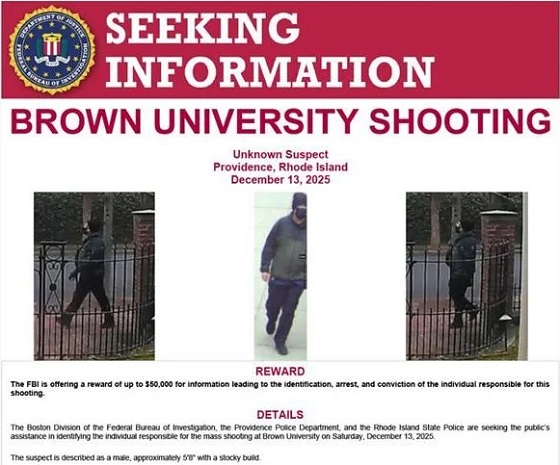

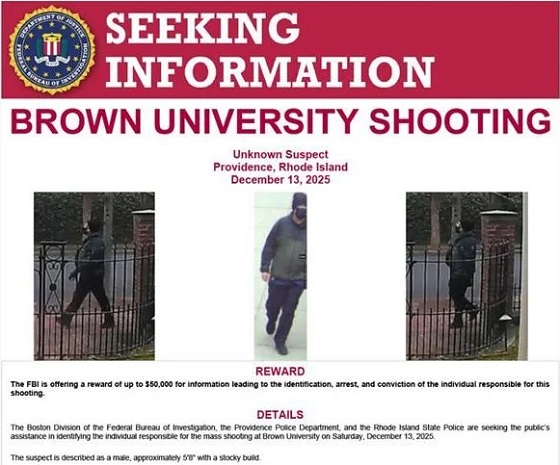

Crime16 hours ago

Crime16 hours agoBrown University shooter dead of apparent self-inflicted gunshot wound

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoCanada Hits the Brakes on Population

-

Crime2 days ago

Crime2 days agoBondi Beach Survivor Says Cops Prevented Her From Fighting Back Against Terrorists

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoHouse Rejects Bipartisan Attempt To Block Trump From Using Military Force Against Venezuela

-

Automotive2 days ago

Automotive2 days agoFord’s EV Fiasco Fallout Hits Hard

-

Frontier Centre for Public Policy1 day ago

Frontier Centre for Public Policy1 day agoCanada Lets Child-Porn Offenders Off Easy While Targeting Bible Believers

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoDanielle Smith slams Skate Canada for stopping events in Alberta over ban on men in women’s sports

-

Agriculture1 day ago

Agriculture1 day agoWhy is Canada paying for dairy ‘losses’ during a boom?