Crime

Despite recent bail reform flip-flops, Canada is still more dangerous than we’d prefer

Our Criminal Justice System Is Changing

58 percent of individuals sentenced to community supervision had at least one prior conviction for a violent offence. 68 percent of those given custodial sentences were similarly repeat offenders. In fact, 59 percent of offenders serving custodial sentences had previously been convicted at least 10 times.

Back in 2019, the federal Liberals passed Bill C-75, “An Act to amend the Criminal Code, the Youth Criminal Justice Act and other Acts”. Among other things, the law established a Principle of Restraint that required courts to minimize unnecessary pre-trial detention. This has been characterized as a form of “catch and release” that sacrifices public safety in general, and victims’ rights in particular on the altar of social justice.

I’m no lawyer, but I can’t see how the legislation’s actual language supports that interpretation. In fact, as we can see from the government’s official overview of the law, courts must still give serious consideration to public safety:

The amendments…legislate a “principle of restraint” for police and courts to ensure that release at the earliest opportunity is favoured over detention, that bail conditions are reasonable, relevant to the offence and necessary to ensure public safety, and that sureties are imposed only when less onerous forms of release are inadequate.

So unlike in some U.S. jurisdictions, Canadian courts are still able use their discretion to restrict an accused’s freedom. That’s not to say everyone’s always happy with how Canadian judges choose to use such discretion, but judicial outcomes appear to lie in their hands, rather than with legislation.

The Audit is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Arguably, C-75 did come with a “soft-on-crime” tone (in particular as the law relates to certain minority communities). But even that was mostly reversed by 2023’s Bill C-48, which introduced reverse onus for repeat offenders and required judges to explicitly consider the safety of the community (whatever that means).

Nevertheless, the system is clearly far from perfect. Besides the occasional high-profile news reports about offenders committing new crimes while awaiting trials for previous offences, the population-level data suggests that our streets are not nearly as safe as they should be.

As far as I can tell, Statistics Canada doesn’t publish numbers on repeat offences committed by offenders free while waiting for trial. But I believe we can get at least part of the way there using two related data points:

- Conviction rates

- Repeat offender rates

Between 2019 and 2023, conviction rates across Canada on homicide charges for adults averaged 42 percent, while similar charges against youth offenders resulted in convictions in 65 percent of cases. That means we can safely assume that a significant proportion of accused offenders were, in fact, criminally violent even before reaching trial.

We can use different Statistics Canada data to understand how likely it is that those accused offenders will re-offend while on pre-trial release:

58 percent of individuals sentenced to community supervision (through either conditional sentences or probation) had at least one prior conviction for a violent offence. 68 percent of those given custodial sentences were similarly repeat offenders. In fact, 59 percent of offenders serving custodial sentences had previously been convicted at least 10 times.

Also, in the three years following a term of community supervision, 15.6 percent of offenders were convicted for new violent crimes. For offenders coming out of custodial sentences, that rate was 30.2 percent.

In other words:

- Many – if not most – people charged with serious crimes turn out to be guilty

- It’s relatively rare for violent criminals to offend just once.

Together, those two conclusions suggest that public safety would be best served by immediately incarcerating all people charged with violent offences and keeping them “inside” either until they’re declared innocent or their sentences end. That, however, would be impossible. For one thing, we just don’t have space in our prisons to handle the load (or the money to fund it). And it would also often trample on the legitimate civil rights of accused individuals.

This is a serious problem without any obvious pull-the-trigger-and-you’re-

- Implement improved risk assessment and predictive analytics tools to evaluate the likelihood of re-offending.

- Improve the reliability of non-custodial measures such as electronic monitoring and house arrest that incorporate real-time tracking and immediate intervention capabilities

- Improve parole and probation systems to ensure effective monitoring and support for offenders released into the community. (Warning: expensive!)

- Optimize data analytics to identify trends, allocate resources efficiently, and measure the effectiveness of various interventions.

The Audit is a reader-supported publication. To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Invite your friends and earn rewards

Crime

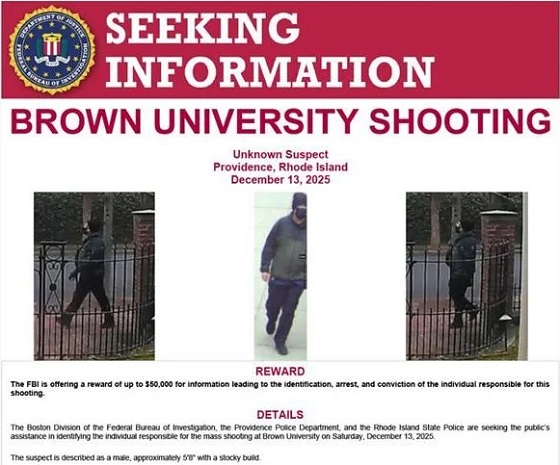

Brown University shooter dead of apparent self-inflicted gunshot wound

From The Center Square

By

Rhode Island officials said the suspected gunman in the Brown University mass shooting has been found dead of an apparent self-inflicted gunshot wound, more than 50 miles away in a storage facility in southern New Hampshire.

The shooter was identified as Claudio Manuel Neves-Valente, a 48-year-old Brown student and Portuguese national. Neves-Valente was found dead with a satchel containing two firearms inside in the storage facility, authorities said.

“He took his own life tonight,” Providence police chief Oscar Perez said at a press conference, noting that local, state and federal law officials spent days poring over video evidence, license plate data and hundreds of investigative tips in pursuit of the suspect.

Perez credited cooperation between federal state and local law enforcement officials, as well as the Providence community, which he said provided the video evidence needed to help authorities crack the case.

“The community stepped up,” he said. “It was all about groundwork, public assistance, interviews with individuals, and good old fashioned policing.”

Rhode Island Attorney General Peter Neronha said the “person of interest” identified by private videos contacted authorities on Wednesday and provided information that led to his whereabouts.

“He blew the case right open, blew it open,” Neronha said. “That person led us to the car, which led us to the name, which led us to the photograph of that individual.”

“And that’s how these cases sometimes go,” he said. “You can feel like you’re not making a lot of progress. You can feel like you’re chasing leaves and they don’t work out. But the team keeps going.”

The discovery of the suspect’s body caps an intense six-day manhunt spanning several New England states, which put communities from Providence to southern New Hampshire on edge.

“We got him,” FBI special agent in charge for Boston Ted Docks said at Thursday night’s briefing. “Even though the suspect was found dead tonight our work is not done. There are many questions that need to be answered.”

He said the FBI deployed around 500 agents to assist local authorities in the investigation, in addition to offering a $50,000 reward. He says that officials are still looking into the suspect’s motive.

Two students were killed and nine others were injured in the Brown University shooting Saturday, which happened when an undetected gunman entered the Barus and Holley building on campus, where students were taking exams before the holiday break. Providence authorities briefly detained a person in the shooting earlier in the week, but then released them.

Investigators said they are also examining the possibility that the Brown case is connected to the killing of a Massachusetts Institute of Technology professor in his hometown.

An unidentified gunman shot MIT professor Nuno Loureiro multiple times inside his home in Brookline, about 50 miles north of Providence, according to authorities. He died at a local hospital on Tuesday.

Leah Foley, U.S. attorney for Massachusetts, was expected to hold a news briefing late Thursday night to discuss the connection with the MIT shooting.

Crime

Bondi Beach Survivor Says Cops Prevented Her From Fighting Back Against Terrorists

From the Daily Caller News Foundation

A woman who survived the Hanukkah terrorist attack at Bondi Beach in Australia said on Monday that police officers seemed less concerned about stopping the attack than they were about keeping her from fighting back.

A father and son of Pakistani descent opened fire on a Hanukkah celebration Sunday, killing at least 15 people and wounding 40, with one being slain on the scene by police and the other wounded and taken into custody. Vanessa Miller told Erin Molan about being separated from her three-year-old daughter during Monday’s episode of the “Erin Molan Show.”

“I tried to grab one of their guns,” Miller said. “Another one grabbed me and said ‘no.’ These men, these police officers, they know who I am. I hope they are hearing this. You are weak. You could have saved so many more people’s lives. They were just standing there, listening and watching this all happen, holding me back.”

Dear Readers:

As a nonprofit, we are dependent on the generosity of our readers.

Please consider making a small donation of any amount here.

Thank you!

WATCH:

“Two police officers,” Miller continued. “Where were the others? Not there. Nobody was there.”

New South Wales Minister of Police Yasmin Catley did not immediately respond to a request for comment from the Daily Caller News Foundation about Miller’s comments.

Australian Prime Minister Anthony Albanese vowed to enact further restrictions on guns in response to the attack at Bondi Beach, according to the Associated Press. The new restrictions would include a limit on how many firearms a person could own, more review of gun licenses, limiting the licenses to Australian citizens and “additional use of criminal intelligence” to determine if a license to own a firearm should be granted.

Sajid Akram, 50, and Naveed Akram, 24, reportedly went to the Philippines, where they received training prior to carrying out the Sunday attack, according to the Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Naveed Akram’s vehicle reportedly had homemade ISIS flags inside it.

Australia passed legislation that required owners of semi-automatic firearms and certain pump-action firearms to surrender them in a mandatory “buyback” following a 1996 mass shooting in Port Arthur, Tasmania, that killed 35 people and wounded 23 others. Despite the legislation, one of the gunmen who carried out the attack appeared to use a pump-action shotgun with an extended magazine.

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day ago“Magnitude cannot be overstated”: Minnesota aid scam may reach $9 billion

-

Haultain Research6 hours ago

Haultain Research6 hours agoSweden Fixed What Canada Won’t Even Name

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoLargest fraud in US history? Independent Journalist visits numerous daycare centres with no children, revealing massive scam

-

Censorship Industrial Complex1 day ago

Censorship Industrial Complex1 day agoUS Under Secretary of State Slams UK and EU Over Online Speech Regulation, Announces Release of Files on Past Censorship Efforts

-

Daily Caller2 days ago

Daily Caller2 days agoIs Ukraine Peace Deal Doomed Before Zelenskyy And Trump Even Meet At Mar-A-Lago?

-

Business5 hours ago

Business5 hours agoWhat Do Loyalty Rewards Programs Cost Us?