Addictions

Critics question conclusions of new Ontario “safer supply” study

A new study links safer supply to health improvements, but critics say results are muddied by methadone use and extra supports

A new study that compares safer supply with a traditional approach to addiction treatment has ignited debate among addiction experts.

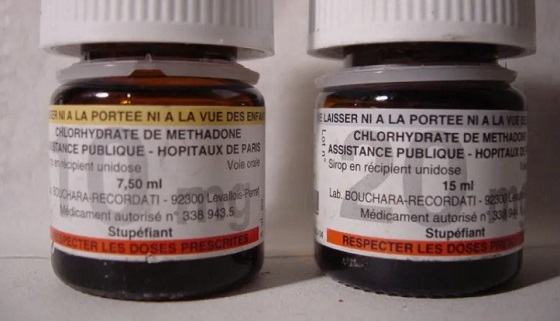

The study, published in The Lancet Public Health in April, examined health outcomes for people receiving safer supply and compared them to a similar group of people receiving methadone, a drug used to reduce drug cravings and withdrawal symptoms.

It concluded that safer supply programs significantly improved participants’ health outcomes. Safer supply provides people at high risk of overdose with prescription opioids as a safer alternative to toxic street drugs.

But critics question the study’s conclusions. They note that many safer supply participants had access to more support services and that the majority also received methadone. These factors make it difficult to identify which treatment drove the positive results.

“The study did not compare [safer supply] to methadone, but rather the initiation of both with several other unaccounted variables,” wrote psychiatrists Dr. Robert Tanguaya and Dr. Nickie Mathew in a formal critique also published in The Lancet.

Findings

The peer-reviewed study is the first in Canada to compare the health outcomes for people receiving safer supply with those receiving methadone through a program known as opioid agonist therapy. Opioid agonist therapy, or OAT, is widely used to treat opioid use disorder.

The study, which was led by teams at Unity Health Toronto, ICES, the University of Toronto and the Ontario Network of People Who Use Drugs, followed about 1,700 Ontarians who started treatment between 2016 and 2021. Half were receiving prescribed hydromorphone through Ontario’s safer supply programs; the other half were receiving methadone through an OAT program.

Participants were tracked for up to one year. Both groups saw improvements, including fewer overdoses, emergency room visits, hospital stays and new infections.

“The findings suggest [safer supply] programs play an important, complementary role to traditional opioid agonist treatment in expanding the options available to support people who use drugs,” the study says.

However, when compared against each other, the safer supply group had higher rates of overdose, ER visits and hospital admissions than those on methadone.

Still, the authors conclude that safer supply can complement methadone, especially for people who do not respond well to traditional options like OAT.

Subscribe for free to get BTN’s latest news and analysis – or donate to our investigative journalism fund.

Confounders

In their May 27 critique in The Lancet Public Health, psychiatrists Tanguay and Mathew say the study fails to isolate the effects of safer supply.

“It is unclear from this study whether the benefits attributed to [safer supply] initiation came from the prescribed … hydromorphone or not,” they wrote.

One concern is that most safer supply participants were also on methadone — a highly dose-dependent medication — and the study did not account for how much of each drug they received.

Dr. Leonara Regenstreif, a primary care physician who specializes in substance use disorders, raised a similar point in an email to Canadian Affairs.

She noted that 84 per cent of safer supply participants in the study were already on methadone when they began receiving hydromorphone.

“It would take a lot of fudging to be able to say [safer supply] was responsible for an outcome, when that group was actually receiving two drugs,” she said.

The main study’s authors did not respond to requests for comment. Instead, they directed Canadian Affairs to their May 27 response to Tanguay and Mathew’s critique, also published in The Lancet.

Wraparound care

Critics also say that improved outcomes among safer supply participants may be due to the extensive additional health care they received while on safer supply.

This additional care was evidenced in study participants’ medication costs.

In the year after treatment began, median medication costs for safer supply patients rose by more than $13,000 per person. By comparison, costs for those on methadone rose by about $1,600.

Glen McGee, a statistics professor at the University of Waterloo, says this suggests safer supply participants may have received broader care, including treatment for other conditions like HIV or hepatitis C.

“This could suggest treatment [of the safer supply group] involved more thorough care in addition to [safer supply], which could also account for some of the improved outcomes,” he said.

In their response to Tanguay and Mathew’s critique, the main study’s authors said the additional care is not a flaw — it reflects how Ontario’s safer supply model is designed.

“Embedding hydromorphone prescriptions within other health and social services that address the complex needs of people at high risk of drug-related harms is a deliberate and defining feature,” they wrote.

McGee suggests the challenge of isolating the impact of broader care makes it difficult to draw broad conclusions about safer supply’s role in patients’ health outcomes.

“The analyses in the main paper seem reasonable, but the conclusions are perhaps too strong,” said McGee. “We don’t necessarily know if [safer supply] alone would be as effective.”

Overdose risk

Critics also focused on safer supply participants having a higher risk of overdose than those in opioid agonist therapy.

Although safer supply patients were more likely to stay in treatment than methadone patients, overdose rates remained higher for safer supply patients — even after adjusting for people who dropped out from the methadone group.

The study authors say this is likely because safer supply patients started at higher risk and many continued using street drugs early in treatment.

“The smaller decline among [safer supply] recipients might reflect higher baseline risk and greater ongoing exposure to the unregulated drug supply early in treatment,” they wrote.

They also noted that very few people died in either group, showing that treatment — whether safer supply or methadone — offers protection.

However, Regenstreif urges caution.

“If you peel away the stats language, underneath it all you have a cohort with higher risks of opioid toxicity and other hazards of ongoing drug use,” said Regenstreif.

This article was produced through the Breaking Needles Fellowship Program, which provided a grant to Canadian Affairs, a digital media outlet, to fund journalism exploring addiction and crime in Canada. Articles produced through the Fellowship are co-published by Break The Needle and Canadian Affairs.

Our content is always free – but if you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism, consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

Addictions

Canada must make public order a priority again

A Toronto park

Public disorder has cities crying out for help. The solution cannot simply be to expand our public institutions’ crisis services

[This editorial was originally published by Canadian Affairs and has been republished with permission]

This week, Canada’s largest public transit system, the Toronto Transit Commission, announced it would be stationing crisis worker teams directly on subway platforms to improve public safety.

Last week, Canada’s largest library, the Toronto Public Library, announced it would be increasing the number of branches that offer crisis and social support services. This builds on a 2023 pilot project between the library and Toronto’s Gerstein Crisis Centre to service people experiencing mental health, substance abuse and other issues.

The move “only made sense,” Amanda French, the manager of social development at Toronto Public Library, told CBC.

Does it, though?

Over the past decade, public institutions — our libraries, parks, transit systems, hospitals and city centres — have steadily increased the resources they devote to servicing the homeless, mentally ill and drug addicted. In many cases, this has come at the expense of serving the groups these spaces were intended to serve.

For some communities, it is all becoming too much.

Recently, some cities have taken the extraordinary step of calling states of emergency over the public disorder in their communities. This September, both Barrie, Ont. and Smithers, B.C. did so, citing the public disorder caused by open drug use, encampments, theft and violence.

In June, Williams Lake, B.C., did the same. It was planning to “bring in an 11 p.m. curfew and was exploring involuntary detention when the province directed an expert task force to enter the city,” The Globe and Mail reported last week.

These cries for help — which Canadian Affairs has also reported on in Toronto, Ottawa and Nanaimo — must be taken seriously. The solution cannot simply be more of the same — to further expand public institutions’ crisis services while neglecting their core purposes and clientele.

Canada must make public order a priority again.

Without public order, Canadians will increasingly cease to patronize the public institutions that make communities welcoming and vibrant. Businesses will increasingly close up shop in city centres. This will accelerate community decline, creating a vicious downward spiral.

We do not pretend to have the answers for how best to restore public order while also addressing the very real needs of individuals struggling with homelessness, mental illness and addiction.

But we can offer a few observations.

First, Canadians must be willing to critically examine our policies.

Harm-reduction policies — which correlate with the rise of public disorder — should be at the top of the list.

The aim of these policies is to reduce the harms associated with drug use, such as overdose or infection. They were intended to be introduced alongside investments in other social supports, such as recovery.

But unlike Portugal, which prioritized treatment alongside harm reduction, Canada failed to make these investments. For this and other reasons, many experts now say our harm-reduction policies are not working.

“Many of my addiction medicine colleagues have stopped prescribing ‘safe supply’ hydromorphone to their patients because of the high rates of diversion … and lack of efficacy in stabilizing the substance use disorder (sometimes worsening it),” Dr. Launette Rieb, a clinical associate professor at the University of British Columbia and addiction medicine specialist recently told Canadian Affairs.

Yet, despite such damning claims, some Canadians remain closed to the possibility that these policies may need to change. Worse, some foster a climate that penalizes dissent.

“Many doctors who initially supported ‘safe supply’ no longer provide it but do not wish to talk about it publicly for fear of reprisals,” Rieb said.

Second, Canadians must look abroad — well beyond the United States — for policy alternatives.

As The Globe and Mail reported in August, Canada and the U.S. have been far harder hit by the drug crisis than European countries.

The article points to a host of potential factors, spanning everything from doctors’ prescribing practices to drug trade flows to drug laws and enforcement.

For example, unlike Canada, most of Europe has not legalized cannabis, the article says. European countries also enforce their drug laws more rigorously.

“According to the UN, Europe arrests, prosecutes and convicts people for drug-related offences at a much higher rate than that of the Americas,” it says.

Addiction treatment rates also vary.

“According to the latest data from the UN, 28 per cent of people with drug use disorders in Europe received treatment. In contrast, only 9 per cent of those with drug use disorders in the Americas received treatment.”

And then there is harm reduction. No other country went “whole hog” on harm reduction the way Canada did, one professor told The Globe.

If we want public order, we should look to the countries that are orderly and identify what makes them different — in a good way.

There is no shame in copying good policies. There should be shame in sticking with failed ones due to ideology.

Our content is always free – but if you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism,

consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

Addictions

No, Addicts Shouldn’t Make Drug Policy

By Adam Zivo

Canada’s policy of deferring to the “leadership” of drug users has proved predictably disastrous. The United States should take heed.

[This article was originally published in City Journal, a public policy magazine and website published by the Manhattan Institute for Policy Research]

Progressive “harm reduction” advocates have insisted for decades that active users should take a central role in crafting drug policy. While this belief is profoundly reckless—akin to letting drunk drivers set traffic laws—it is now entrenched in many left-leaning jurisdictions. The harms and absurdities of the position cannot be understated.

While the harm-reduction movement is best known for championing public-health interventions that supposedly minimize the negative effects of drug use, it also has a “social justice” component. In this context, harm reduction tries to redefine addicts as a persecuted minority and illicit drug use as a human right.

This campaign traces its roots to the 1980s and early 1990s, when “queer” activists, desperate to reduce the spread of HIV, began operating underground needle exchanges to curb infections among drug users. These exchanges and similar efforts allowed some more extreme LGBTQ groups to form close bonds with addicts and drug-reform advocates. Together, they normalized the concept of harm reduction, such that, within a few years, needle exchanges would become officially sanctioned public-health interventions.

The alliance between these more radical gay rights advocates and harm-reduction proponents proved enduring. Drug addiction remained linked to HIV, and both groups shared a deep hostility to the police, capitalism, and society’s “moralizing” forces.

In the 1990s, harm-reduction proponents imitated the LGBTQ community’s advocacy tactics. They realized that addicts would have greater political capital if they were considered a persecuted minority group, which could legitimize their demands for extensive accommodations and legal protections under human rights laws. Harm reductionists thus argued that addiction was a kind of disability, and that, like the disabled, active users were victims of social exclusion who should be given a leading role in crafting drug policy.

These arguments were not entirely specious. Addiction can reasonably be considered a mental and physical disability because illicit drugs hijack users’ brains and bodies. But being disabled doesn’t necessarily mean that one is part of a persecuted group, much less that one should be given control over public policy.

More fundamentally, advocates were wrong to argue that the stigma associated with drug addiction was senseless persecution. In fact, it was a reasonable response to anti-social behavior. Drug addiction severely impairs a person’s judgement, often making him a threat to himself and others. Someone who is constantly high and must rob others to fuel his habit is a self-evident danger to society.

Despite these obvious pitfalls, portraying drug addicts as a persecuted minority group became increasingly popular in the 2000s, thanks to several North American AIDS organizations that pivoted to addiction work after the HIV epidemic subsided.

In 2005, the Canadian HIV/AIDS Legal Network published a report titled “Nothing about us without us.” (The nonprofit joined other groups in publishing an international version in 2008.) The 2005 report included a “manifesto” written by Canadian drug users, who complained that they were “among the most vilified and demonized groups in society” and demanded that policymakers respect their “expertise and professionalism in addressing drug use.”

The international report argued that addiction qualified as a disability under international human rights treaties, and called on governments to “enact anti-discrimination or protective laws to reduce human rights violations based on dependence to drugs.” It further advised that drug users be heavily involved in addiction-related policy and decision-making bodies; that addict-led organizations be established and amply funded; and that “community-based organizations . . . increase involvement of people who use drugs at all levels of the organization.”

While the international report suggested that addicts could serve as effective policymakers, it also presented them as incapable of basic professionalism. In a list of “do’s and don’ts,” the authors counseled potential employers to pay addicts in cash and not to pass judgment if the money were spent on drugs. They also encouraged policymakers to hold meetings “in a low-key setting or in a setting where users already hang out,” and to avoid scheduling meetings at “9 a.m., or on welfare cheque issue day.” In cases where addicts must travel for policy-related work, the report recommended policymakers provide “access to sterile injecting equipment” and “advice from a local person who uses drugs.”

The international report further asserted that if an organization’s employees—even those who are former drug users—were bothered by the presence of addicts, then management should refer those employees to counselling at the organization’s expense. “Under no circumstances should [drug addicts] be reprimanded, singled out or made to feel responsible in any way for the triggering responses of others,” stressed the authors.

Reflecting the document’s general hostility to recovery, the international report emphasized that former drug addicts “can never replace involvement of active users” in public policy work, because people in recovery “may be somewhat disconnected from the community they seek to represent, may have other priorities than active users, may sometimes even have different and conflicting agenda, and may find it difficult to be around people who currently use drugs.”

Subscribe for free to get BTN’s latest news and analysis – or donate to our investigative journalism fund.

The messaging in these reports proved highly influential throughout the 2000s and 2010s. In Canada, federal and provincial human rights legislation expanded to protect active addicts on the basis of disability. Reformers in the United States mirrored Canadian activists’ appeals to addicts’ “lived experience,” albeit with less success. For now, American anti-discrimination protections only extend to people who have a history of addiction but who are not actively using drugs.

The harm reduction movement reached its zenith in the early 2020s, after the Covid-19 pandemic swept the world and instigated a global spike in addiction. During this period, North American drug-reform activists again promoted the importance of treating addicts like public-health experts.

Canada was at the forefront of this push. For example, the Canadian Association of People Who Use Drugs released its “Hear Us, See Us, Respect Us” report in 2021, which recommended that organizations “deliberately choose to normalize the culture of drug use” and pay addicts $25-50 per hour. The authors stressed that employers should pay addicts “under the table” in cash to avoid jeopardizing access to government benefits.

These ideas had a profound impact on Canadian drug policy. Throughout the country, public health officials pushed for radical pro-drug experiments, including giving away free heroin-strength opioids without supervision, simply because addicts told researchers that doing so would be helpful. In 2024, British Columbia’s top doctor even called for the legalization of all illicit drugs (“non-medical safer supply”) primarily on the basis of addict testimonials, with almost no other supporting evidence.

For Canadian policymakers, deferring to the “lived experiences” and “leadership” of drug users meant giving addicts almost everything they asked for. The results were predictably disastrous: crime, public disorder, overdoses, and program fraud skyrocketed. Things have been less dire in the United States, where the harm reduction movement is much weaker. But Americans should be vigilant and ensure that this ideology does not flower in their own backyard.

Subscribe to Break The Needle.

Our content is always free – but if you want to help us commission more high-quality journalism,

consider getting a voluntary paid subscription.

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoTrump says U.S. in ‘armed conflict’ with drug cartels in Caribbean

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoJobs Critic says NDP government lied to British Columbians and sold out Canadian workers in billion dollar Chinese ferries purchase

-

Indigenous2 days ago

Indigenous2 days agoBloodvein First Nation blockade puts public land rights at risk

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoDemocracy Watch Drops a Bomb on Parliament Hill

-

Alberta15 hours ago

Alberta15 hours agoJason Kenney’s Separatist Panic Misses the Point

-

Automotive12 hours ago

Automotive12 hours agoBig Auto Wants Your Data. Trump and Congress Aren’t Having It.

-

espionage1 hour ago

espionage1 hour agoStarmer Faces Questions Over Suppressed China Spy Case, Echoing Trudeau’s Beijing Scandals