International

Climate contrarians have the president’s ear

Made-in-American climate assessment challenges IPCC modelling, introducing alternative projections and recommendations that are shaping national conversations on environmental strategy and scientific credibility.

At the end of July, the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) released a report on climate change that seemed surprisingly optimistic.

There’s good news and bad news. First, the bad news: We only have five years to live.

That’s according to U.S. Congresswoman Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who, you may recall, warned in January 2019: “The world is going to end in 12 years if we don’t address climate change.”

The good news is that AOC may have been exaggerating just a wee bit. And so has the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), according to the DOE’s Climate Working Group.

That’s my layman’s interpretation of what the 150-page DOE report says.

It mainly takes issue with climate models used by the IPCC. These models run too “hot” and, as a result, predict things like temperatures or extreme weather events that are not borne out by observation.

The report also notes that the IPCC appears to bury one positive consequence of more CO2 in the atmosphere: global “greening.”

They also question the assumptions that a warming planet necessarily has led to – or will lead to – increased extreme weather events.

Now, it should be noted that the report’s five authors are considered climate science heretics and contrarians, and their report has been dismissed and repudiated by 85 establishment scientists as “misleading or fundamentally incorrect.”

I would note that two of the group’s five authors — John Christy and Judith Curry — have both contributed to past IPCC assessments as lead or contributing authors. They’re not cranks – they are legit climate scientists who just happen to disagree with the “consensus” on some basic points.

The report was commissioned by U.S. Energy Secretary Chris Wright to provoke “a more thoughtful and science-based conversation about climate change and energy.”

“What I’ve found is that media coverage often distorts the science,” Wright says in a foreword to the report.

One such distortion is the repeated use of a worst-case scenario for warming (RCP8.5) that is considered so unlikely as to be “implausible,” but which produces better headlines and gets more grants than more probable, less scary scenarios for warming.

The five scientists and academics selected for the DOE’s climate working group are well-known for their climate science heterodoxy — Christy, Curry, Steven Koonin, Roy Spencer and Ross McKitrick (the sole Canadian on the team.)

Neither Wright nor the report’s authors deny the climate is changing. That would be hard to do. The earth has been warming ever since we came out of the last Ice Age.

The $122 trillion question is just how much the more recent heating has been the result of burning of fossil fuels. (It’s estimated that to hit net zero targets, we will need to spend US$3.5 trillion a year until 2050.)

“Climate change is real, and it deserves attention,” says Wright in the report. “But it is not the greatest threat facing humanity. That distinction belongs to global energy poverty.”

Pay attention, Canada. Like it or not, this is where America’s head is at right now. It is bumping climate action down the priority list and bumping up energy security and affordability, and if our own policies on environment and energy are too misaligned with America’s, we will continue to put our economy at a disadvantage.

Polling confirms there has been shift in attitude in just the last couple of years on climate and energy. On the hierarchy of fears, it appears climate change no longer tops the list.

Even Greta Thunberg took a sabbatical from climate activism to go fight the Israelites from a flotilla of diesel-burning boats in the Levant.

The climate catastrophism and alarmism that reached peak mania in 2019 may have led to both fatalism and fatigue. The DOE report goes some way to explaining where this fatigue and fatalism may be coming from.

Basically, it comes from environmentalists, politicians and the media taking worst-case scenarios from the IPCC and scaring the shit out of everyone with apocalyptic doomsaying.

Here are some highlights of the report, as I see it:

- modeling used by the IPCC may be tuned too “hot,” resulting in predicted global temperature increases that are not borne out by observable temperature data;

- IPCC assessments downplay the positive consequences of global “greening” resulting from increased amounts of CO2 in the atmosphere;

- worst-case scenarios for warming used by the IPCC are wholly improbable; and

- There is no evidence of long-term extreme weather events as a consequence of warming.

According to the DOE report, the models used by the IPCC for predicting climate sensitivity to CO2 predict temperature increases that are higher than actual observed temperature increases.

“The combination of overly sensitive models and implausible extreme scenarios for future emissions yields exaggerated projections of future warming,” the authors conclude.

When I reached McKitrick by phone, he explained what they mean by running too hot.

“There is a long-standing, almost universal pattern among the models, overstating the response to CO2 in the troposphere,” McKitrick told me. “Models warm too much. The models exhibit too much warming in response to rising CO2 and that also translates into too much surface warming.”

In more recent assessments, the IPCC has used a range of scenarios to predict how the planet might respond to increased GHGs. These scenarios – called Representative Concentration Pathways – range from RCP2.6 to RCP8.5.

RCP2.6 predicts global warming of below 2 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial temperatures. RCP8.5 predicts temperature increases of 5 degrees between 1900 and 2100 — which might indeed produce some hellish consequences.

AOC and Thunberg would be right to worry about this kind of temperature increase, if it were remotely plausible, and if nothing were being done to address GHG emissions.

The report notes that RCP8.5 came to be referred to as the no-policy baseline, or “business-as-usual” scenario. That’s the scenario in which nothing is done to try to reduce emissions.

But things are being done to reduce emissions. Efforts are being made the world over to adopt electric cars, phase out coal power, install wind and solar power, and capture and store CO2. So this worst-case scenario is probably not useful.

“The problem is, it’s routinely used in a lot of academic articles as what they call the business as usual outcome,” McKitrick said. “And most of the climate impact stories you see in the press are based on studies running RCP8.5. So you get these lurid outcomes of total devastation.

“It’s not just the IPCC. That’s a problem with the literature as a whole. Authors want to have the big, frightening splashy result, and then their article will get written up in the press.”

In 2020, Zeke Hausfather and Glen Peters wrote in Nature that the overuse of RCP8.5 as a business scenario “has resulted in a large number of misleading studies and media reporting.”

They characterized RCP8.5 as “implausible.”

“We must all …stop presenting the worst-case scenarios as the most likely one,” Hausfather and Peters wrote. “Overstating the likelihood of extreme climate impacts can make mitigation seem harder than it actually is.”

In other words, everyone reporting on climate change needs to tone things down a little. You’re scaring the children.

The DOE report criticizes the IPCC for downplaying one positive result of increased CO2 in the atmosphere — global greening.

It notes that “CO2 fertilization” had driven an increase in observed global photosynthesis by 30% since 1900, “versus 17% predicted by plant models.”

“The IPCC has minimally discussed global greening,” the authors note, but it is omitted in IPCC summary documents. These summary documents are the only ones that non-scientists (like journalists and politicians) tend to read, so it’s a bit of a buried story.

“This is a very important topic because rising CO2 levels have contributed to a massive greening of the planet,” McKitrick said. “On the agricultural front, there’s evidence that it has contributed substantially to crop productivity. And it also makes plants more tolerant to heat.

“There’s nothing controversial about those statements. They’re well established. But it’s never been pointed out in IPCC summaries.”

As for extreme weather events, modelling suggests that a warming planet should result in increased frequency and severity of things like hurricanes, droughts, and floods.

The report concludes that observational data suggests no long-term trend with respect to extreme weather events:

“Most extreme weather events in the U.S. do not show long-term trends,” the report states. “Claims of increased frequency or intensity of hurricanes, tornadoes, floods, and droughts are not supported by U.S. historical data.”

Generally, the DOE report posits a “lukewarmer” position on climate change – i.e. that the earth is warming, but that this may be more the result of natural causes, like solar activity, and less likely the result of CO2.

If this position is correct, it means the world will have spent trillions already on an energy transition that wasn’t necessary.

If this theory is wrong, then that investment in decarbonization and the energy transition is basically an insurance policy.

Nelson Bennett’s column appears weekly at Resource Works News. Contact him at [email protected].

Health

The Data That Doesn’t Exist

ACIP voted to un-recommend the Hep B birth dose, but here’s the problem: they still can’t weigh the other side of the ledger

Sunday, something happened that has never happened in the history of American public health: ACIP voted 8-3 to un-recommend the universal birth dose of hepatitis B for babies born to mothers who test negative for the virus. After 34 years of jabbing every American newborn within hours of taking their first breath—regardless of whether their mother had hepatitis B—the committee finally acknowledged what 25 European countries figured out decades ago: it doesn’t make sense.

But watching this vote unfold, I couldn’t help but notice the absurdity of the debate itself. Committee members who opposed the change kept saying variations of the same thing: “We’ve heard ‘do no harm’ as a moral imperative. We are doing harm by changing this wording.” Another said “no rational science has been presented” to support the change.

How to End the Autism Epidemic is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

And therein lies the fundamental problem with ACIP—and with the entire vaccine regulatory apparatus in America. They literally cannot weigh risk versus benefit because they only have data on one side of the scale.

The Missing Side of the Ledger

When ACIP debates adding or removing a vaccine from the schedule, they can produce endless data on disease incidence. They can show you charts demonstrating how hepatitis B cases in infants dropped from thousands to single digits after 1991. They can model projected infections if vaccination rates decline. They have this data at their fingertips because tracking infectious disease is something our public health apparatus actually does.

But ask them to produce equivalent data on vaccine injury, and you’ll get silence. Not “the data shows injuries are rare.” Not “here’s our comprehensive tracking of adverse events.” Just… nothing. A void where information should be.

This is not an accident. This is by design.

The safety trials for Engerix-B and Recombivax HB—the two hepatitis B vaccines given to American newborns—monitored adverse events for four to five days after injection. That’s it. If your baby developed seizures on day six, or regressed into autism over the following months, or developed autoimmune disease in the following year—none of that would appear in the pre-licensure safety data.

And the post-market surveillance? VAERS is a voluntary reporting system that the CDC itself acknowledges captures only a tiny fraction of adverse events. A Harvard-funded study found it captures perhaps 1% of actual vaccine injuries. Vaccine court has paid out over $5 billion in claims while simultaneously being structured to make filing nearly impossible for average families.

So when Dr. Cody Meissner voted against removing the Hep B birth dose and said he saw “clear evidence of the benefits” but “not the harms,” he was accidentally revealing the entire rotten structure. Of course he doesn’t see the harms. Nobody is systematically looking for them.

The Invisibility of Vaccine Injury

Here’s what most people don’t understand about vaccine injury: it’s nothing like a gunshot wound.

If you shoot someone, the cause is obvious. There’s a bullet, a wound, blood, a clear mechanism of action visible to any observer. Even a medical examiner who’s never seen the victim before can determine cause of death.

Vaccine injury doesn’t work that way. When aluminum nanoparticles from a vaccine cross the blood-brain barrier via macrophages, when they lodge in brain tissue and trigger chronic neuroinflammation, when a child slowly regresses over weeks or months—there’s no bullet. There’s no smoking gun. There’s just a before and an after, and a desperate parent trying to explain to doctors that something changed.

This invisibility is the vaccine program’s greatest protection. Because the injury mechanism is complex and delayed, because it doesn’t leave an obvious wound, because it requires actually looking to find—and because no one in authority is looking—the injuries simply don’t exist in the official record.

I watched my own son Jamie regress after his vaccines. A healthy, developing toddler who lost his words, stopped making eye contact, and retreated into a world we couldn’t reach. My wife and I know what happened. Thousands of other parents know the same thing happened to their children. But because this type of injury doesn’t show up on a simple blood test, because there’s no autopsy finding that says “vaccine-induced encephalopathy,” ACIP members can sit in a room and say with straight faces that they don’t see evidence of harm.

They’re not lying. They literally can’t see it. Because no one is measuring it.

The Chicken Pox Conundrum

Here’s an example that illustrates the insanity of our current approach.

The varicella (chicken pox) vaccine was added to the schedule in 1995. It definitely reduces chicken pox cases. The data is clear on that front. Mission accomplished, right?

But what about the other side of the ledger?

Emerging research suggests that wild chicken pox infection provides some protective effect against brain cancers—particularly glioma, the most common type of primary brain tumor. Multiple studies have found that people who had chicken pox as children have significantly lower rates of brain cancer later in life. The hypothesis is that the immune response to wild varicella provides lasting immunological benefits that extend far beyond preventing itchy spots.

Meanwhile, the vaccine itself has been associated with increased rates of autoimmune conditions. Studies have linked varicella vaccination to higher rates of herpes zoster (shingles) outbreaks in younger age groups, to autoimmune disorders, to various adverse events that weren’t captured in the original short-term safety trials.

So what’s the true risk-benefit of the chicken pox vaccine? Does preventing a week of itchy discomfort in childhood justify potentially increased rates of brain cancer and autoimmune disease later in life?

ACIP can’t answer this question. They literally don’t have the data. They can show you chicken pox cases going down. They cannot show you a comprehensive analysis of long-term neurological and immunological outcomes in vaccinated versus unvaccinated populations, because that study has never been done.

And so they keep recommending the vaccine based on the only data they have—the disease prevention data—while remaining willfully blind to consequences they’ve never bothered to measure.

The ACIP Paradox

Sunday’s vote was historic, but it also revealed the fundamental paradox of vaccine regulation in America.

The committee members who voted to remove the universal Hep B birth dose recommendation did so largely based on comparative evidence from Europe, parental concerns, and the basic logic that vaccinating a 12-hour-old baby for a sexually transmitted disease their mother doesn’t have makes no medical sense. They were right to do so.

But the committee members who voted against the change weren’t wrong either, from their perspective. They looked at the only data they have—disease prevention data—and concluded that removing the recommendation could lead to more hepatitis B cases. And within their limited framework, they’re correct.

The problem is the framework itself.

True risk-benefit analysis requires data on both risks AND benefits. ACIP has comprehensive data on benefits (disease prevention) and virtually no data on risks (vaccine injury). So every decision they make is fundamentally flawed from the start.

When Dr. Joseph Hibbeln complained that “no rational science has been presented” to support changing the recommendations, he was inadvertently indicting the entire system. Of course no comprehensive vaccine injury data was presented—such data doesn’t exist because no one has been willing to collect it.

This is like asking someone to make an informed financial decision while only showing them potential profits and hiding all possible losses. Of course the decision will be skewed. Of course you’ll end up with a bloated portfolio of high-risk investments that look great on paper.

The Real Reform

If RFK Jr. and the new HHS leadership want to actually fix the vaccine program, they need to understand that removing individual vaccines or making them “optional” is just rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

The real reform is creating the data infrastructure that should have existed from the beginning.

We need a comprehensive, long-term, vaccinated-versus-unvaccinated health outcomes study. Not a five-day safety trial. A multi-decade tracking of neurological, immunological, and developmental outcomes across populations with varying vaccination status. Florida just eliminated all vaccine mandates—that state alone could provide the data we need within ten years if someone had the courage to actually collect it.

We need a vaccine injury surveillance system that actually captures adverse events. Not a voluntary reporting system that misses 99% of injuries. An active surveillance system with trained clinicians looking for the kinds of delayed, complex injuries that vaccines actually cause.

We need accountability for manufacturers. The 1986 National Childhood Vaccine Injury Act removed all liability from vaccine makers—and predictably, the vaccine schedule exploded afterward while safety research stagnated. Why would any company invest in safety when they can’t be sued for injuries?

Without this data, every ACIP meeting will be the same performance we watched this week: members confidently citing disease prevention data while admitting they can’t see evidence of harm—not because harm doesn’t exist, but because no one is looking for it.

What Comes Next

Sunday’s vote was a crack in the wall. For the first time, an American regulatory body acknowledged that perhaps vaccinating every newborn within hours of birth for a disease primarily transmitted through sex and IV drug use doesn’t make sense when the mother has already tested negative.

But the forces of institutional inertia are already mobilizing. The American Academy of Pediatrics is “disappointed.” The American Medical Association is calling for the CDC to reject the recommendation. The pharmaceutical industry—which collects over $225 million annually from Hep B birth doses alone—will fight to restore the universal recommendation.

They will cite the same data they always cite: disease prevention data. Cases prevented. Infections avoided. Lives saved—theoretically.

They will not cite vaccine injury data, because that data doesn’t exist in any comprehensive form. They will not present long-term health outcomes in vaccinated versus unvaccinated children, because those studies have been actively avoided for decades. They will not acknowledge the thousands of families who have watched their children regress after vaccination, because those injuries aren’t captured in any official database.

And this is why ACIP will always be hamstrung. Until we build the data infrastructure to actually measure vaccine injury—to put real numbers on the other side of the ledger—every vaccine decision will be based on incomplete information. Every “risk-benefit analysis” will be a fraud, because we’re only measuring half the equation.

The hepatitis B birth dose vote was a small victory. But the larger battle—for actual science, for complete data, for true informed consent—that battle is just beginning.

And until we win it, ACIP will continue making decisions in the dark, confidently citing evidence of benefits while remaining deliberately blind to the harms they’ve never bothered to measure.

About the author

J.B. Handley is the proud father of a child with Autism. He spent his career in the private equity industry and received his undergraduate degree with honors from Stanford University. His first book, How to End the Autism Epidemic, was published in September 2018. The book has sold more than 75,000 copies, was an NPD Bookscan and Publisher’s Weekly Bestseller, broke the Top 40 on Amazon, and has more than 1,000 Five-star reviews. Mr. Handley and his nonspeaking son are also the authors of Underestimated: An Autism Miracle and co-produced the film SPELLERS, available now on YouTube.

How to End the Autism Epidemic is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support my work, consider becoming a free or paid subscriber.

Business

The Climate-Risk Industrial Complex and the Manufactured Insurance Crisis

We’ve all seen the headlines — such as the below — loudly proclaiming that due to climate change the insurance industry is in crisis, and even that total economic collapse may soon follow. For instance, since 2019, the New York Times, one of the primary champions of this narrative, has published more than 1,250 articles on climate change and insurance.

Climate advocates have embraced the idea of a climate-fueled insurance crisis as it neatly ties together the hyping of extreme weather and alleged financial consequences for ordinary people. The oft-cited remedy to the claimed crisis is, of course, to be found in energy policy: “The only long-term solution to preserve an insurable future is to transition from fossil fuels and other greenhouse-gas-emitting industries.”

However, it is not just climate advocates promoting the notion that climate change is fundamentally threatening the insurance industry. A climate-risk industrial complex has emerged in this space and a lot of money is being made by a lot of people. The virtuous veneer of climate advocacy serves to discourage scrutiny and accountability.

In this series, I take a deep dive into the “crisis,” its origins, its politics, and its tenuous relationship with actual climate science.¹ Today, I kick things off by sharing three fundamental, and perhaps surprising, facts that go a long way to explaining why insurance prices have increased and who benefits:

- Property/casualty insurance is raking in record profits;

- Insurance underwriting returns vary year-to-year but show no trend;

- “Climate” risk assessments are unreliable and a cause of higher insurance prices.

Grab a cup of coffee, settle in, and let’s go . . .

If you value the deep dives such as this one, which you will find no where else,

please consider supporting THB with a paid subscription!

Property/casualty insurance is raking in record profits

This year is shaping up to be an extremely profitable year for the property/casualty (P/C) insurance industry. In a report covering the first six months of 2025, the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC) shares the good news (emphasis added):

Despite heavy catastrophe losses, including the costliest wildfires on record, the U.S. Property & Casualty (P&C) industry recorded its best mid-year underwriting gain in nearly 20 years.

In the second half of 2025, returns got even better for the P/C industry. According to a new report from S&P Global Intelligence, as reported by Carrier Management (emphases added):

For U.S. P/C insurers, it just doesn’t get any better than this. . . With a combined ratio of 89.1 for third-quarter 2025, the U.S. property/casualty insurance industry had its best quarter in at least a quarter of a century—and maybe longer, S&P Market Intelligence said.

Taking a longer view, the extremely profitable 2025 follows significant industry profitability in 2023 and 2024, according to the National Association of Insurance Commissioners (NAIC), as shown in the figure below.

|

What accounts for the high profits?

The NAIC explains:

Strong premium growth, driven largely by rate increases, coupled with abating economic inflation . . . Net income nearly doubled compared to last year, attributed to the underwriting profit and healthy investment returns.

Below, I’ll pick up the issue of rate increases and explore one big reason why they have occurred.

If there is a P/C insurance crisis, it may be in figuring out how to explain its impressive returns at the same time that the climate lobby is telling everyone that the industry is collapsing.

Insurance underwriting returns vary year-to-year but show no trend

The P/C industry makes money primarily in two ways — underwriting of insurance policies and investment income. Typically, insurance companies seek to break even, or lose little, on insurance underwriting and earn profits on investment income.

Warren Buffet, in his 2009 letter to Berkshire Hathaway shareholders, explained concisely how the P/C industry works:

Our property-casualty (P/C) insurance business has been the engine behind Berkshire’s growth and will continue to be. It has worked wonders for us. We carry our P/C companies on our books at $15.5 billion more than their net tangible assets, an amount lodged in our “Goodwill” account. These companies, however, are worth far more than their carrying value– and the following look at the economic model of the P/C industry will tell you why.

Insurers receive premiums upfront and pay claims later. In extreme cases, such as those arising from certain workers’ compensation accidents, payments can stretch over decades. This collect-now, pay-later model leaves us holding large sums– money we call “float”– that will eventually go to others. Meanwhile, we get to invest this float for Berkshire’s benefit. Though individual policies and claims come and go, the amount of float we hold remains remarkably stable in relation to premium volume. Consequently, as our business grows, so does our float.

If premiums exceed the total of expenses and eventual losses, we register an underwriting profit that adds to the investment income produced from the float. This combination allows us to enjoy the use of free money– and, better yet, get paid for holding it. Alas, the hope of this happy result attracts intense competition, so vigorous in most years as to cause the P/C industry as a whole to operate at a significant underwriting loss. This loss, in effect, is what the industry pays to hold its float. Usually this cost is fairly low, but in some catastrophe-ridden years the cost from underwriting losses more than eats up the income derived from use of float.

The figure below, using data from the Insurance Information Institute, shows the underwriting performance of the P/C industry from 2004 to 2024.

The time series shows lots of ups and downs, but no trend — by design, as Buffet explained. There are certainly no signs of an underwriting crisis, much less indications of a coming collapse. The P/C industry looks both well-managed and healthy.

“Climate” risk assessments are unreliable and a cause of higher insurance prices

|

If profits are high and underwriting is steady, then what then accounts for increasing insurance prices — which, as of the end of 2024, increased 29 consecutive quarters in a row (above)?

A big part of the answer is Climate Change. But not how you might think.

A decade ago, Mark Carney — then Governor of the Bank of England and today Prime Minister of Canada — gave an influential speech titled, Breaking the Tragedy of the Horizon – climate change and financial stability.

Carney argued that the insurance industry was at risk due to changes in the climatology of extreme events that were not properly understood by experts in the industry:

[T]here are some estimates that currently modelled losses could be undervalued by as much as 50% if recent weather trends were to prove representative of the new normal. . . Such developments have the potential to shift the balance between premiums and claims significantly, and render currently lucrative business non-viable.

Coincident with Carney’s 2015 speech, the Bank of England released a report on the impacts of climate change on the insurance industry, and noted that conventional catastrophe modeling did not effectively consider a changing climate. The Bank of England kicked off a longstanding campaign to convince people that extreme weather events were changing dramatically in the near term.

Subsequently, in 2019, the Bank of England required firms to assess their “climate risks.” This guidance was updated last week. In (a coordinated) parallel effort, national and international organizations focused on “climate risk” to the financial sector started multiplying — such as the Climate Financial Risk Forum and the Network for Greening the Financial System.

The climate-risk industry was born circa 2019.

There is an incredible story to be told here (and Jessica Weinkle is the go-to expert), but for today, the key takeaways are that (a) the notion of “climate risk” to finance, including insurance, led to the creation of a “climate risk” industry, and (b) within this industry, a new family of risk assessment vendors emerged, promising to satisfy the new demands for climate risk disclosure and risk modeling.

The Global Association of Risk Professionals (GARP) explains:

As this [“climate risk”] was a new discipline for most financial firms, many turned to third party providers (“vendors”) to help them with different areas of expertise. There are now many physical risk data vendors, which offer a variety of services to financial institutions. While vendor offerings often sound alike — providing projections of how physical risk could evolve for locations across a range of risks and climate scenarios — they can differ significantly in terms of features, approach, or suitability for specific needs, and the underlying models that these providers use differ in methodology and assumptions.

GARP just published an incredibly important study that assessed how 13 different “climate risk” vendors modeled physical risk and risk of loss across 100 individual structures around the world.²

The results are shocking — given how they are used in industry, but should not be surprising — given what we know about modeling.

There is absolutely no consensus across vendors about “climate risk” in terms of either physical risks or risks of loss.

The figure below shows, for 100 different properties around the world, the differences in modeled 200-year flood risk across the 13 vendors, as refelcted in modeled flood heights. The maximum difference among the properties across vendors is about 12 meters and the median difference is about 2.7 meters — These are huge differences.

|

In terms of risk of loss, the models have an even greater spread. The figure below shows that for a modeled 200-year flood, 10 properties are modeled by at least one vendor to have total losses (100%) while another vendor models the same properties to have no losses, under the exact same event. The median difference between minimum and maximum modeled loss ratio is 30% — Another huge number.³

|

Insurance pricing does not scale linearly with increasing modeled loss ratios. Consider that the difference between a modeled 10% loss ratio and a 40% loss ratio (i.e., the 30% median difference across vendors from above) might result in a 10x increase in insurance rates. Risk adverse insurers have incentives to price at the most extreme modeled loss.

Model inaccuracies, unceratinties, spread, and ambiguity are feature not flaws when it comes to making money. “Climate risk” modeling has resulted in a financial windfall not just for the newly created climate analytics industry, but also for insurers and reinsurers who have seen the envelope of modeled losses expand. The need for new models, of questionabl fidelity, are necessary to satisfy industry guidance and government regulators.

The net result has been a seemingly scientific justification for increasing insurance rates.⁴

There are of course real changes in physical risk, exposure, and vulnerability as well as the regulatory and political contexts within which the P/C industry must operate. The discipline of catastrophe modeling has long integrated these factors to assess risks. As insurance policies and reinsurance contracts are typically implemented on a one-year basis, and this well-positioned to incorporate changng perceptions of risk, this series will explore why a new “climate risk” assessment industry was even needed in the first place.

What about that “climate risk”? THB readers will be very familiar with the science of extreme events and climate change, which, as reported here, happens to be consistent with both the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change and those in the legacy catastrophe modeling community.

One of those modeling firms, Verisk, gets the last word for today:

We estimate about 1% of year-on-year increases in AAL [Average Annual Loss] are attributable to climate change. Such small shifts can easily get lost behind other sources of systematic loss increase discussed in this report, such as inflation and exposure growth. The random volatility from internal climate variability also dwarfs the small positive climate change signal.

Before you go — If you learned something from this post, please click that “ Like” button — More likes mean that THB rises in the Substack algorithm and gets in front of more readers. More readers mean that THB reaches more people in more places, broadening understandings and discussions of complex issues where science meets politics. Thanks!

Like” button — More likes mean that THB rises in the Substack algorithm and gets in front of more readers. More readers mean that THB reaches more people in more places, broadening understandings and discussions of complex issues where science meets politics. Thanks!

Comments, questions, discussion, critique — all welcome!

If you value THB please consider subscribing. Paid subscribers make THB go and also have access to THB Pro, with PDFs of some of my books, THB Insider, Five Figures, and paywalled THB posts. Plus you get to participate in the lively, diverse, and informed discussions under every post. Thank you!

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoWhy Does Canada “Lead” the World in Funding Racist Indoctrination?

-

Media2 days ago

Media2 days agoThey know they are lying, we know they are lying and they know we know but the lies continue

-

Focal Points2 days ago

Focal Points2 days agoThe West Needs Bogeymen (Especially Russia)

-

Censorship Industrial Complex1 day ago

Censorship Industrial Complex1 day agoUS Condemns EU Censorship Pressure, Defends X

-

Dan McTeague1 day ago

Dan McTeague1 day agoWill this deal actually build a pipeline in Canada?

-

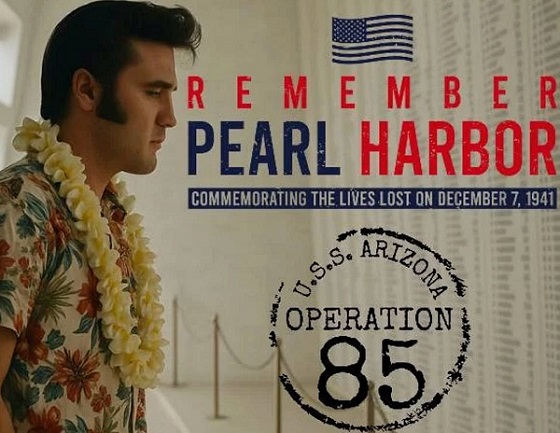

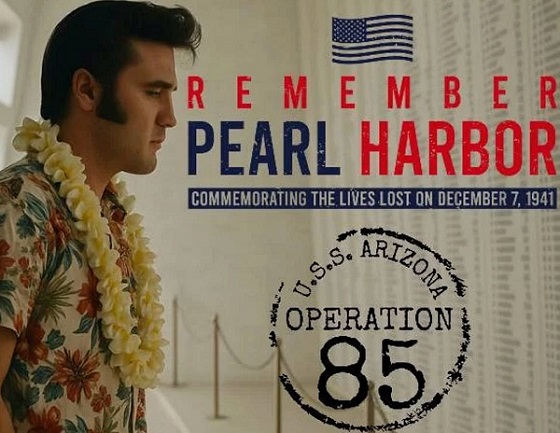

Opinion1 day ago

Opinion1 day agoThe day the ‘King of rock ‘n’ roll saved the Arizona memorial

-

Bruce Dowbiggin16 hours ago

Bruce Dowbiggin16 hours agoWayne Gretzky’s Terrible, Awful Week.. And Soccer/ Football.

-

Banks1 day ago

Banks1 day agoTo increase competition in Canadian banking, mandate and mindset of bank regulators must change