Environment

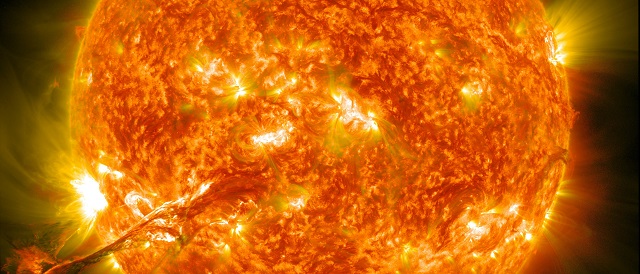

Climate Alarmists Want To Fight The Sun. What Could Possibly Go Wrong?

From the Daily Caller News Foundation

From the Daily Caller News Foundation

What should we say when one of America’s pre-eminent media platforms endorses a plan so fraught with unknowns and pitfalls it invites potential global catastrophe?

That’s what the editorial board at the Washington Post did on April 27 in a 1,000-word editorial endorsing plans by radical schemers and billionaires to engage in various efforts at geoengineering.

The Post’s editors engage in an exercise of saying the quiet part out loud in the piece, morphing from referring to monkeying around with the world’s ability to absorb sunlight as “a forbidden subject,” to concluding it is “indispensable” and “urgent” in the course of a single opinion piece. Sure, why not? What could possibly go wrong with such a plan?

What could go wrong with plans to, say, block sunlight with thousands of high-altitude balloons? Or with a plan that involves spraying the upper atmosphere with billions of tons of sulfur particles? Or with a plan to spend trillions of debt-funded dollars to build a gargantuan shield placed in stationary orbit in outer space?

The editors are so cocksure in their arrogance that they even admit some such concepts have already been tried out, writing, “Climate geoengineering is so cheap and potentially game-changing that even private entrepreneurs have tried it out, albeit at small scales.”

The “small scale” experiment to which the editors refer took place in Baja, Mexico, where researchers launched two large balloons filled with sulfur dioxide particles into the stratosphere. The goal was to measure the sun-dimming effects of the sulfur dioxide, a real, actual pollutant that the Environmental Protection Agency and regulators all over the world have spent the last half century attempting to remove from the atmosphere.

It turned out that Luke Eisman, an entrepreneur who financed the experiment, launched the balloons without seeking prior approval. When Mexican officials found out it had been conducted, they quickly moved to ban such geo-engineering projects on the grounds that they violate national sovereignty. Reuters reports that Mexico’s environment ministry statement said it would seek a global moratorium on such geoengineering projects under the Convention on Biological Diversity.

But despite such concerns in Mexico, here come the Post’s editors advocating we simply just have to trust the science. You know, like we trusted the “science” of COVID vaccines and the “science” of locating giant offshore wind farms in the middle of a whale migration corridor off the Northeast coast, right? Sure. After all, what could go wrong?

The editorial writers go on to cite a similar, larger scale project being promoted by climate-engineering scholars David Keith at the University of Chicago and Wake Smith at Yale. These gentlemen propose to try to lower temperatures by spewing out 100,000 tons of sulfur dioxide – again, a real pollutant humanity has worked decades to eliminate – at an annual cost of $500 million (no doubt to be paid for by more taxpayer debt) using what they refer to as “15 souped-up Gulfstream jets” to create what could accurately be called chemtrails.

In a piece published in February at the MIT Technology Review, the scientists say the project could be mounted as soon as five years from now, which we should all probably consider a threat rather than a mere projection.

Talk of mounting similar geoengineering projects has been ramping up in recent years. In 2021, Bill Gates said he was investing in a project based at Harvard University to spray tons of calcium carbonate particles into the stratosphere above Scandinavia, but the project was ultimately cancelled due to understandable outrage from indigenous groups and environmentalists.

Fellow billionaires Jeff Bezos and Facebook co-founder Dustin Moskovitz have also plowed millions into bioengineering projects.

But until recently, the thought of mounting projects designed to block out sunlight was, like the agenda to intentionally reduce the global population, a subset of their agenda that climate alarmists have tried to keep mainly under wraps. The reason is obvious: Whenever such radical and frankly dangerous ideas are made public, people tend to look at one another and ask, “who in the world would want to do that?”

Now come the members of the Washington Post editorial board, joining Gates and Bezos and Moskovitz in answering that question. Way to go, folks.

David Blackmon is an energy writer and consultant based in Texas. He spent 40 years in the oil and gas business, where he specialized in public policy and communications.

Agriculture

The Climate Argument Against Livestock Doesn’t Add Up

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

Livestock contribute far less to emissions than activists claim, and eliminating them would weaken nutrition, resilience and food security

The war on livestock pushed by Net Zero ideologues is not environmental science; it’s a dangerous, misguided campaign that threatens global food security.

The priests of Net Zero 2050 have declared war on the cow, the pig and the chicken. From glass towers in London, Brussels and Ottawa, they argue that cutting animal protein, shrinking herds and pushing people toward lentils and lab-grown alternatives will save the climate from a steer’s burp.

This is not science. It is an urban belief that billions of people can be pushed toward a diet promoted by some policymakers who have never worked a field or heard a rooster at dawn. Eliminating or sharply reducing livestock would destabilize food systems and increase global hunger. In Canada, livestock account for about three per cent of total greenhouse gas emissions, according to Environment and Climate Change Canada.

Activists speak as if livestock suddenly appeared in the last century, belching fossil carbon into the air. In reality, the relationship between humans and the animals we raise is older than agriculture. It is part of how our species developed.

Two million years ago, early humans ate meat and marrow, mastered fire and developed larger brains. The expensive-tissue hypothesis, a theory that explains how early humans traded gut size for brain growth, is not ideology; it is basic anthropology. Animal fat and protein helped build the human brain and the societies that followed.

Domestication deepened that relationship. When humans raised cattle, sheep, pigs and chickens, we created a long partnership that shaped both species. Wolves became dogs. Aurochs, the wild ancestors of modern cattle, became domesticated animals. Junglefowl became chickens that could lay eggs reliably. These animals lived with us because it increased their chances of survival.

In return, they received protection, veterinary care and steady food during drought and winter. More than 70,000 Canadian farms raise cattle, hogs, poultry or sheep, supporting hundreds of thousands of jobs across the supply chain.

Livestock also protected people from climate extremes. When crops failed, grasslands still produced forage, and herds converted that into food. During the Little Ice Age, millions in Europe starved because grain crops collapsed. Pastoral communities, which lived from herding livestock rather than crops, survived because their herds could still graze. Removing livestock would offer little climate benefit, yet it would eliminate one of humanity’s most reliable protections against environmental shocks.

Today, a Maasai child in Kenya or northern Tanzania drinking milk from a cow grazing on dry land has a steadier food source than a vegan in a Berlin apartment relying on global shipping. Modern genetics and nutrition have pushed this relationship further. For the first time, the poorest billion people have access to complete protein and key nutrients such as iron, zinc, B12 and retinol, a form of vitamin A, that plants cannot supply without industrial processing or fortification. Canada also imports significant volumes of soy-based and other plant-protein products, making many urban vegan diets more dependent on long-distance supply chains than people assume. The war on livestock is not a war on carbon; it is a war on the most successful anti-poverty tool ever created.

And what about the animals? Remove humans tomorrow and most commercial chickens would die of exposure, merino sheep would overheat under their own wool and dairy cattle would suffer from untreated mastitis (a bacterial infection of the udder). These species are fully domesticated. Without us, they would disappear.

Net Zero 2050 is a climate target adopted by federal and provincial governments, but debates continue over whether it requires reducing livestock herds or simply improving farm practices. Net Zero advocates look at a pasture and see methane. Farmers see land producing food from nothing more than sunlight, rain and grass.

So the question is not technical. It is about how we see ourselves. Does the Net Zero vision treat humans as part of the natural world, or as a threat that must be contained by forcing diets and erasing long-standing food systems? Eliminating livestock sends the message that human presence itself is an environmental problem, not a participant in a functioning ecosystem.

The cow is not the enemy of the planet. Pasture is not a problem to fix. It is a solution our ancestors discovered long before anyone used the word “sustainable.” We abandon it at our peril and at theirs.

Dr. Joseph Fournier is a senior fellow at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy. An accomplished scientist and former energy executive, he holds graduate training in chemical physics and has written more than 100 articles on energy, environment and climate science.

Environment

Canada’s river water quality strong overall although some localized issues persist

From the Fraser Institute

By Annika Segelhorst and Elmira Aliakbari

Canada’s rivers are vital to our environment and economy. Clean freshwater is essential to support recreation, agriculture and industry, an to sustain suitable habitat for wildlife. Conversely, degraded freshwater can make it harder to maintain safe drinking water and can harm aquatic life. So, how healthy are Canada’s rivers today?

To answer that question, Environment Canada uses an index of water quality to assess freshwater quality at monitoring stations across the country. In total, scores are available for 165 monitoring stations, jointly maintained by Environment Canada and provincial authorities, from 17 in Newfoundland and Labrador, to 8 in Saskatchewan and 20 in British Columbia.

This index works like a report card for rivers, converting water test results into scores from 0 to 100. Scientists sample river water three or more times per year at fixed locations, testing indicators such as oxygen levels, nutrients and chemical levels. These measurements are then compared against national and provincial guidelines that determine the ability of a waterway to support aquatic life.

Scores are calculated based on three factors: how many guidelines are exceeded, how often they are exceeded, and by how much they are exceeded. A score of 95-100 is “excellent,” 80-94 is “good,” 65-79 is “fair,” 45-64 is “marginal” and a score below 45 is “poor.” The most recent scores are based on data from 2021 to 2023.

Among 165 river monitoring sites across the country, the average score was 76.7. Sites along four major rivers earned a perfect score: the Northeast Magaree River (Nova Scotia), the Restigouche River (New Brunswick), the South Saskatchewan River (Saskatchewan) and the Bow River (Alberta). The Bayonne River, a tributary of the St. Lawrence River near Berthierville, Quebec, scored the lowest (33.0).

Overall, between 2021 and 2023, 83.0 per cent of monitoring sites across the country recorded fair to excellent water quality. This is a strong positive signal that most of Canada’s rivers are in generally healthy environmental condition.

A total of 13.3 per cent of stations were deemed to be marginal, that is, they received a score of 45-64 on the index. Only 3.6 per cent of monitoring sites fell into the poor category, meaning that severe degradation was limited to only a few sites (6 of 165).

Monitoring sites along waterways with relatively less development in the river’s headwaters and those with lower population density tended to earn higher scores than sites with developed land uses. However, among the 11 river monitoring sites that rated “excellent,” 8 were situated in areas facing a combination of pressures from nearby human activities that can influence water quality. This indicates the resilience of Canada’s river ecosystems, even in areas facing a combination of multiple stressors from urban runoff, agriculture, and industrial activities where waterways would otherwise be expected to be the most polluted.

Poor or marginal water quality was relatively more common in monitoring sites located along the St. Lawrence River and its major tributaries and near the Great Lakes compared to other regions. Among all sites in the marginal or poor category, 50 per cent were in this area. The Great Lakes-St. Lawrence region is one of the most population-dense and extensively developed parts of Canada, supporting a mix of urban, agricultural, and industrial land uses. These pressures can introduce harmful chemical contaminants and alter nutrient balances in waterways, impairing ecosystem health.

In general, monitoring sites categorized as marginal or poor tended to be located near intensive agriculture and industrial activities. However, it’s important to reiterate that only 28 stations representing 17.0 per cent of all monitoring stations were deemed to be marginal or poor.

Provincial results vary, as shown in the figure below. Water quality scores in Newfoundland and Labrador, Prince Edward Island, New Brunswick, Saskatchewan and Alberta were, on average, 80 points or higher during the period from 2021 to 2023, indicating that water quality rarely departed from natural or desirable levels.

Rivers sites in Nova Scotia, Ontario, Manitoba and B.C. each had average scores between 74 and 78 points, suggesting occasional departures from natural or desirable levels.

Finally, Quebec’s average river water quality score was 64.5 during the 2021 to 2023 period. This score indicates that water quality departed from ideal conditions more frequently in Quebec than in other provinces, especially compared to provinces like Alberta, Saskatchewan and P.E.I. where no sites rated below “fair.”

Overall, these results highlight Canada’s success in maintaining a generally high quality of water in our rivers. Most waterways are in good shape, though some regions—especially near the Great Lakes and along the St. Lawrence River Valley—continue to face pressures from the combined effects of population growth and intensive land use.

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoLargest fraud in US history? Independent Journalist visits numerous daycare centres with no children, revealing massive scam

-

Haultain Research22 hours ago

Haultain Research22 hours agoSweden Fixed What Canada Won’t Even Name

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days ago“Magnitude cannot be overstated”: Minnesota aid scam may reach $9 billion

-

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days ago

Censorship Industrial Complex2 days agoUS Under Secretary of State Slams UK and EU Over Online Speech Regulation, Announces Release of Files on Past Censorship Efforts

-

Business22 hours ago

Business22 hours agoWhat Do Loyalty Rewards Programs Cost Us?

-

Business10 hours ago

Business10 hours agoLand use will be British Columbia’s biggest issue in 2026

-

Energy10 hours ago

Energy10 hours agoWhy Japan wants Western Canadian LNG

-

Business7 hours ago

Business7 hours agoMainstream media missing in action as YouTuber blows lid off massive taxpayer fraud