Indigenous

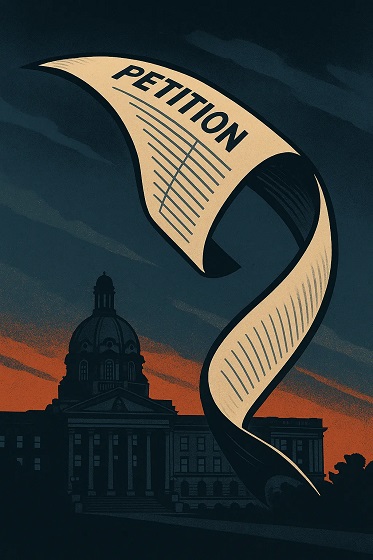

B.C.’s plan to ‘reconcile’ by giving First Nations a veto on land use

From the MacDonald Laurier Institute

By Bruce Pardy

UNDRIP-inspired land law reforms are poised to turn province into an untenable host for mining, forestry and much more.

We live in strange times. A new generation of political leaders seems determined to cripple their own societies. Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, of course, comes to mind. But in Canada, he is not alone. In British Columbia, NDP Premier David Eby is preparing to bring his province to its knees.

The B.C. government plans to share management of Crown land with First Nations. The scheme will apply not to limited sections of public land here and there, but across the province. The government quietly opened public consultations on the proposal last week. According to the scant materials, the government will amend the B.C. Land Act to incorporate agreements with Indigenous governing bodies.

These agreements will empower B.C.’s hundreds of First Nations to make joint decisions with the minister responsible for the Land Act, the main law under which the provincial government grants leases, licences, permits and rights-of-way over Crown land. That means that First Nations will have a veto over how most of B.C. is used. Joint management can be expected to apply to mining, hydro projects, farming, forestry, docks and communication towers, just to start. Activities at the heart of B.C.’s economy will be at risk.

In 2007, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP). UNDRIP states, among other things, that Indigenous people own the land and resources of the countries in which they live. They have “the right to the lands, territories and resources which they have traditionally owned, occupied or otherwise used or acquired … to own, use, develop and control.”

At the time, Canada sensibly voted “no,” along with the United States, Australia and New Zealand. Eleven countries abstained. In 2016, Trudeau’s government reversed Canada’s objection.

As a General Assembly declaration, UNDRIP is not binding in international law nor enforceable in domestic courts. But in 2019, under the leadership of Eby’s predecessor John Horgan, the B.C. legislature passed Bill 41, the Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act. The act requires the government of B.C. to “take all measures necessary to ensure the laws of British Columbia are consistent with the Declaration.” Eby’s joint management plan is the next step in this project.

Long before UNDRIP, the Supreme Court of Canada created a constitutional “duty to consult” with Aboriginal peoples. The court said that the “honour of the Crown” governs the relationship between the government and Aboriginal people. The Crown’s fiduciary duties include a duty to consult whenever proposed action may adversely affect established or asserted Aboriginal rights under Section 35 of the Constitution. This duty is notoriously uncertain, onerous and time-consuming. It has become an albatross around the neck of the Canadian resource industry. The courts seem unable to specify what the duty to consult requires, except after the fact.

Now, the B.C. government aims to make things even more unpredictable. Whatever the contours of the right to be consulted, the Supreme Court at least has been clear that it does not constitute a veto. Eby will create one.

Shortly before the B.C. legislature passed Bill 41 in November 2019, the Continuing Legal Education Society of British Columbia sponsored an Aboriginal Law Conference featuring several Indigenous proponents of the bill. They promised that the new law would render the province unrecognizable.

It will “set up a whole new norm,“ “give teeth to (UNDRIP),” and move the province away, if “not fully,” from the Westminster model of governance. The veto to be conferred on Indigenous interest groups, they said, will mean that “consent will not be given very often, if at all.”

“We’re not talking small changes; we’re talking big changes,” one speaker suggested, adding that money provided by the government so far hasn’t been enough.

“Compensation for sacred sites, for lands taken, for relocation … it’s going to be an overwhelming number of compensation claims … and so I’m hoping that the province is ready for that…. Life (in B.C.) can and will change.”

For many, it is likely to change for the worse. B.C. could become an untenable host for land-based, resource-related enterprise. Impenetrable layers of red tape would entangle applications for leases and licenses. The price for First Nations approvals could be an increasing share of royalties and kickbacks, without which consent will be refused. Both governments and First Nations will siphon an ever-larger piece of a shrinking pie.

The government’s timeline is short. Written submissions will be accepted until the end of March, and anyone giving feedback will be limited by how little information the B.C. government has offered in the consultation. Bureaucrats will begin drafting amendments to the Land Act in early February, and the government plans to introduce a bill in April or May.

If you are feeling grateful not to live in B.C., don’t count your chickens. In 2021, Parliament passed its own version of B.C.’s Bill 41, the federal United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act. It requires the federal government to “take all measures necessary to ensure that the laws of Canada are consistent with the Declaration.” An action plan outlining more than 100 specific measures was released in 2023.

In a speech to the B.C. Business Council in 2016, I argued that our leaders could not do a better job of preventing Canadian business from succeeding in the global economy. I underestimated them. Their determination and ingenuity know no bounds.

Bruce Pardy is executive director of Rights Probe, professor of law at Queen’s University, and senior fellow with the Macdonald-Laurier Institute.

illegal immigration

EXCLUSIVE: Canadian groups, First Nation police support stronger border security

First Nation police chiefs join Texas Department of Public Safety marine units to patrol the Rio Grande River in Hidalgo County, Texas. L-R: Dwayne Zacharie, President of the First Nations Chiefs of Police Association, Ranatiiostha Swamp, Chief of Police of the Akwesasne Mohawk Territory, Brooks County Sheriff Benny Martinez, Jamie Tronnes, Center for North American Prosperity and Security, Goliad County Sheriff Roy Boyd. Photo: Bethany Blankley for The Center Square

From The Center Square

By

Despite Canadian officials arguing that the “Canada-U.S. border is the best-managed and most secure border in the world,” some Canadian groups and First Nation tribal police chiefs disagree.

This week, First Nation representatives traveled to Texas for the first time in U.S.-Canadian history to find ways to implement stronger border security measures at the U.S.-Canada border, including joining an Operation Lone Start Task Force, The Center Square exclusively reported.

Part of the problem is getting law enforcement, elected officials and the general public to understand the reality that Mexican cartels and transnational criminal organizations are operating in Canada; another stems from Trudeau administration visa policies, they argue.

When it comes to public perception, “If you tell Canadians we have a cartel problem, they’ll laugh at you. They don’t believe it. If you tell them we have a gang problem, they will absolutely agree with you 100%. They don’t think that gangs and cartels are the same thing. They don’t see the Hells Angels as equal to the Sinaloa Cartel because” the biker gang is visible, wearing vests out on the streets and cartel operatives aren’t, Jamie Tronnes, executive director of the Center of North American Prosperity and Security, told The Center Square in an exclusive interview.

The center is a US-based project of the MacDonald-Laurier Institute, the largest think tank in Canada. Tronnes previously served as a special assistant to the cabinet minister responsible for immigration and has a background in counterterrorism. She joined First Nation police chiefs to meet with Texas law enforcement and officials this week.

Another Canadian group, Future Borders Coalition, argues, “Canada has become a critical hub for transnational organized crime, with networks operating through its ports, banks, and border communities.” The Sinaloa and Jalisco New Generation Mexican cartels control the fentanyl, methamphetamine and cocaine business in Canada, partnering with local gangs like the Hells Angels and Chinese Communist Party (CCP)-linked actors, who launder profits through casinos, real estate, and shell companies in Vancouver and Toronto, Ammon Blair, a senior fellow at the Texas Public Policy Foundation, and others said at a coalition event prior to First Nation police chiefs and Tronnes coming to Texas.

“The ’Ndrangheta (Italian Mafia) maintains powerful laundering and import operations in Ontario and Quebec, while MS-13 and similar Central American gangs facilitate human smuggling and enforcement. Financial networks tied to Hezbollah and other Middle Eastern groups support laundering and logistics for these criminal alliances,” the coalition reports.

“Together, they form interconnected, technology-driven enterprises that exploit global shipping, cryptocurrency, and AI-enabled communications to traffic whatever yields profit – narcotics, weapons, tobacco, or people. Taking advantage of Canada’s lenient disclosure laws, fragmented jurisdictions, and weak cross-border coordination, these groups have embedded themselves within legitimate sectors, turning Canada into both a transit corridor and safe haven for organized crime,” the coalition reports.

Some First Nation reservations impacted by transnational crime straddle the U.S.-Canada border. One is the Akwesasne Mohawk Reservation, located in Ontario, Quebec, and in two upstate New York counties, where human smuggling and transnational crime is occurring, The Center Square reported. Another is the Tsawwassen First Nation (TWA) Reservation, located in a coastal region south of Vancouver in British Columbia stretching to Point Roberts in Washington state, which operates a ferry along a major smuggling corridor.

Some First Nation reservations like the TWA are suffering from CCP organized crime, Tronnes said. Coastal residents observe smugglers crossing their back yards, going through the reserve; along Canada’s western border, “a lot of fentanyl is being sent out to Asia but it’s also being made in Canada,” Tronnes said.

Transnational criminal activity went largely unchecked under the Trudeau government, during which “border security, national security and national defense were not primary concerns,” Tronnes told The Center Square. “It’s not to say they weren’t concerns, but they weren’t top of mind concerns. The Trudeau government preferred to focus on things like climate change, international human rights issues, a feminist foreign policy type of situation where they were looking more at virtue signaling rather than securing the country.”

Under the Trudeau administration, the greatest number of illegal border crossers, including Canadians, and the greatest number of known, suspected terrorists (KSTs) were reported at the U.S.-Canada border in U.S. history, The Center Square first reported. They include an Iranian with terrorist ties living in Canada and a Canadian woman who tried to poison President Donald Trump, The Center Square reported.

“Had it been a priority for the government to really crack down and provide resources for national security,” federal, provincial and First Nation law enforcement would be better equipped, funded and staffed, Tronnes said. “They would have better ways to understand what’s really happening at the border.”

In February, President Donald Trump for the first time in U.S. history declared a national emergency at the northern border and ordered U.S. military intervention. Months later, his administration acknowledged the majority of fentanyl and KSTs were coming from Canada, The Center Square reported.

Under a new government and in response to pressure from Trump, Canada proposed a $1.3 billion border plan. However, more is needed, the groups argue, including modernizing border technology and an analytics infrastructure, reforming disclosure and privacy rules to enable intelligence sharing, and recognizing and fully funding First Nation police, designating them as essential services and essential to border security.

“National security doesn’t exist without First Nation policing at the border,” Dwayne Zacharie, First Nations Chiefs of Police president, told The Center Square.

Business

UNDRIP now guides all B.C. laws. BC Courts set off an avalanche of investment risk

From Resource Works

Gitxaala has changed all the ground rules in British Columbia reshaping the risks around mills, mines and the North Coast transmission push.

The British Columbia Court of Appeal’s decision in Gitxaala v. British Columbia (Chief Gold Commissioner) is poised to reshape how the province approves and defends major resource projects, from mills and mines to new transmission lines.

In a split ruling on 5 December, the court held that British Columbia’s Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples Act makes consistency with the United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples a question courts can answer. The majority went further, saying UNDRIP now operates as a general interpretive aid across provincial law and declaring the Mineral Tenure Act’s automatic online staking regime inconsistent with article 32(2).

University of Saskatchewan law professor Dwight Newman, who has closely followed the case, says the majority has stretched what legislators thought they were doing when they passed the statute. He argues that section 2 of British Columbia’s UNDRIP law, drafted as a purpose clause, has been turned from guidance for reading that Act into a tool for reading all provincial laws, shifting decisions that were meant for cabinet and the legislature toward the courts.

The decision lands in a province already coping with legal volatility on land rights. In August, the Cowichan Tribes title ruling raised questions about the security of fee simple ownership in parts of Richmond, with critics warning that what used to be “indefeasible” private title may now be subject to senior Aboriginal claims. Newman has called the resulting mix of political pressure, investor hesitation and homeowner anxiety a “bubbling crisis” that governments have been slow to confront.

Gitxaala’s implications reach well beyond mining. Forestry communities are absorbing another wave of closures, including the looming shutdown of West Fraser’s 100 Mile House mill amid tight fibre and softwood duties. Industry leaders have urged Ottawa to treat lumber with the same urgency as steel and energy, warning that high duties are squeezing companies and towns, while new Forests Minister Ravi Parmar promises to restore prosperity in mill communities and honour British Columbia’s commitments on UNDRIP and biodiversity, as environmental groups press the government over pellet exports and protection of old growth.

At the same time, Premier David Eby is staking his “Look West” agenda on unlocking about two hundred billion dollars in new investment by 2035, including a shift of trade toward Asia. A centrepiece is the North Coast Transmission Line, a grid expansion from Prince George to Bob Quinn Lake that the government wants to fast track to power new mines, ports, liquefied natural gas facilities and data centres. Even as Eby dismisses a proposed Alberta to tidewater oil pipeline advanced under a new Alberta memorandum as a distraction, Gitxaala means major energy corridors will also be judged against UNDRIP in court.

Supporters of the ruling say that clarity is overdue. Indigenous nations and human rights advocates who backed the appeal have long argued that governments sold UNDRIP legislation as more than symbolism, and that giving it judicial teeth will front load consultation, encourage genuine consent based agreements and reduce the risk of late stage legal battles that can derail projects after years of planning.

Critics are more cautious. They worry that open ended declarations about inconsistency with UNDRIP will invite strategic litigation, create uncertainty around existing approvals and tempt courts into policy making by another name, potentially prompting legislatures to revisit UNDRIP statutes altogether. For now, the judgment leaves British Columbia with fewer excuses: the province has built its growth plans around big, nation building projects and reconciliation framed as partnership with Indigenous nations, and Gitxaala confirms that those partnerships now have a hard legal edge that will shape the next decade of policy and investment.

Resource Works News

-

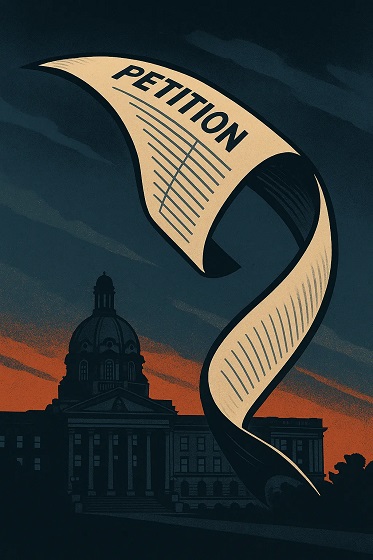

Alberta1 day ago

Alberta1 day agoThe Recall Trap: 21 Alberta MLA’s face recall petitions

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoTyler Robinson shows no remorse in first court appearance for Kirk assassination

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoHigh-speed rail between Toronto and Quebec City a costly boondoggle for Canadian taxpayers

-

illegal immigration1 day ago

illegal immigration1 day agoUS Notes 2.5 million illegals out and counting

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoThe world is no longer buying a transition to “something else” without defining what that is

-

Energy1 day ago

Energy1 day agoCanada’s future prosperity runs through the northwest coast

-

Daily Caller21 hours ago

Daily Caller21 hours ago‘There Will Be Very Serious Retaliation’: Two American Servicemen, Interpreter Killed In Syrian Attack

-

illegal immigration2 days ago

illegal immigration2 days agoEXCLUSIVE: Canadian groups, First Nation police support stronger border security