Business

B.C. Credit Downgrade Signals Deepening Fiscal Trouble

Dan Knight

Dan Knight

Spending is up, debt is exploding, and taxpayers are footing the bill—how David Eby’s reckless economics just pushed British Columbia one step closer to the brink.

So here’s something they’re not going to explain on CBC—British Columbia just got slapped with yet another credit downgrade. Actually, two. On April 2nd, both S&P Global and Moody’s—two of the most powerful financial watchdogs on the planet—downgraded B.C.’s credit rating. And not by accident. This wasn’t a glitch in the system or some market hiccup. This was a direct consequence of political recklessness.

Let’s talk numbers. S&P cut B.C.’s rating from ‘AA-’ to ‘A+’. Moody’s dropped it from ‘aa1’ to ‘aa2’. That’s the fourth downgrade in four years. Four. This is a province that used to hold AAA status—the financial gold standard. That means British Columbia was once considered one of the most fiscally stable jurisdictions not just in Canada, but globally. Not anymore.

Even more alarming? S&P didn’t just hit their long-term rating—they downgraded the short-term rating too, from ‘A-1+’ to ‘A-1’. Why? Because even in the short term, B.C. is starting to look like a risk. A liquidity risk. That means the money might not be there when it’s needed. That’s a red flag for anyone with a calculator and a memory longer than five minutes.

This is not some vague bureaucratic move. This is a direct indictment of the NDP’s economic policies in British Columbia. This is what happens when you treat taxpayers like an ATM machine and the economy like a social experiment. And now, international financial institutions are officially saying what a lot of people have been screaming for years: B.C. is in serious fiscal trouble.

Causes: Spending, Deficits, and Revenue Pressure

The core driver behind the downgrades is the ballooning of operating and capital deficits, coupled with aggressive government spending. According to B.C.’s 2025 budget, unveiled by Finance Minister Brenda Bailey on March 4, the provincial deficit is projected to hit $10.9 billion in 2025–26—up from $9.1 billion the previous year. Moody’s projects an even higher shortfall of $14.3 billion, raising red flags about B.C.’s ability to fund programs without unsustainable borrowing.

S&P cited the impact of reduced immigration levels and ongoing trade uncertainty as key headwinds, limiting economic growth and shrinking the province’s revenue base. Moody’s pointed to persistent budgetary gaps and limited progress on deficit reduction, highlighting the growing gap between revenue and expenditure.

Additionally, spending growth has significantly outpaced both population and inflation. Data from the Fraser Institute shows that between 2019/20 and 2024/25, program spending increased by 51.6%, whereas only 29.2% was needed to keep pace with demographic and price trends. This excess has pushed real per-capita expenditures to historic highs, without a corresponding rise in revenue.

Opposition Blames NDP Mismanagement for Downgrade

But what does that actually mean for real people—not bureaucrats, not lobbyists—but the mom on a fixed income buying groceries? So I reached out to John Rustad, leader of the Official Opposition in B.C., to ask exactly that.

“Two downgrades! Absolute disaster,” he told me. “Under David Eby, we’ve gone from a AAA status to a single A with a negative outlook. This government’s reckless spending and irresponsible management will have a devastating effect—not just today, but for generations to come.”

He’s not exaggerating. According to Rustad, by the end of this fiscal period, B.C.’s debt will have nearly tripled since the NDP took power. Let that sink in—tripled. And no, this isn’t just some abstract macroeconomic trend. This hits you. Directly.

Rustad laid it out. These downgrades mean higher borrowing costs for the province. That’s code for more taxpayer money getting funneled into interest payments instead of hospitals, schools, or—God forbid—tax relief.

“By the end of this fiscal plan, even before the downgrade and before the loss of billions in carbon tax revenue, interest payments were projected to hit $7 billion annually,” Rustad said. “That’s about 30% of personal income tax revenue—just to pay the interest.”

That’s money you send to Victoria every month—just lighting it on fire.

And with the downgrade? Expect to pay another $1 billion more in interest. That’s around $200 per person, per year. Not for roads. Not for services. Just to keep the debt monster fed.

Meanwhile, Premier David Eby—well, he’s had months to plan for replacing the carbon tax, and guess what? Still no plan. Rustad told me he expected Eby to raise industrial taxes to make up the difference, but even that hasn’t happened yet. For now, the hole is just growing—a $2 billion loss in carbon tax revenue on top of an $11 billion deficit.

So What Does This Mean for the Average Mom?

In response to a direct question about what this credit downgrade means for a mother living on a fixed income, Opposition Leader John Rustad laid out the long-term consequences in no uncertain terms:

“The average person will not notice this immediately. But what it does mean is higher borrowing costs, So with the massive deficit and debt, more money will need to be spent on interest payments. By the end of this fiscal, before loss of billions in carbon tax revenue and before the debt downgrades, interest payments would increase to about $7 billion by the end of the fiscal plan. To put that in perspective, that would be the equivalent of 30% or more of personal income taxes just to pay interest.”

He continued:

“The debt downgrades mean the province will have to pay more in interest—likely 1/4 to 1/2% more. On $220+ billion, that could mean $1 billion more in interest. That could be about $200 per man, woman and child annually in more interest by 2027.”

And with no plan to rein in spending, Rustad issued a stark warning:

“The compounding problem is: will this mean service cuts, more taxes, or yet more debt to be paid by our children?”

Final Thoughts

So here’s a question no one on CBC is going to ask: What actually happens when a progressive government can’t manage a budget? I’ll tell you. You get poorer. That’s what happens. You, the person who gets up every day and works a real job, pays the price while the people in charge keep living large off your labour.

Let’s walk through it. First, you pay provincial income tax—a tax just for working. Imagine that. You go out, earn a living, and the government takes a cut just because you dared to be productive. Then there’s the PST—you buy something, anything, and you get taxed again. Why? Because you had the audacity to participate in the economy.

And then there’s the carbon tax, the holy grail of progressive grifts. This wasn’t about saving the planet—it was about propping up the very same government that couldn’t manage a piggy bank, let alone a provincial budget. That tax was floating David Eby’s spending addiction. Now it’s gone, and surprise—there’s no plan to replace it. Just more debt, more interest, and more economic chaos.

But wait—here’s the part that really insults your intelligence. After taxing you into the ground, they turn around and say, “Don’t worry, we’ll give you a rebate.” A rebate? You mean you’re going to give me back a tiny fraction of the money you stole from me and act like you’re doing me a favour? Please. That’s not generosity—it’s gaslighting. It’s economic abuse wrapped in a government cheque.

And that’s why I keep saying it: fiscal responsibility matters. Because I’d rather have that money in my wallet, feeding my kids, paying my bills, building my future—than watching David Eby burn it on pet projects, political theatre, and bloated bureaucracy.

But here’s the thing—there is hope. It’s not all doom and despair. In the last election, something incredible happened. The BC Conservatives, a party written off by the elites and ignored by the media, pulled off a political miracle. They surged from obscurity to contention—why? Because regular people are waking up. Because the voters who pay the bills, raise the kids, and still believe in common sense are done being treated like ATMs for a government that doesn’t even pretend to respect them.

And maybe—just maybe—after a little more pain, after a little more David Eby-style financial recklessness, the voters of this province will finally realize why fiscal responsibility matters. Not because it sounds good in a press release, but because without it, your future vanishes. Your freedom shrinks. And the people in charge? They just keep spending.

So next time, when the ballots are counted and the smoke clears, maybe British Columbia will finally remember who this province belongs to—not to bureaucrats, not to activists, not to the political class in Victoria—but to you.

And that day can’t come soon enough.

Business

Canada’s attack on religious charities makes no fiscal sense

This article supplied by Troy Media.

By Lee Harding

By Lee Harding

Ottawa is targeting the charitable tax status of faith-based groups. The fallout could hit every Canadian community

The possibility that Canadian religious organizations will lose their charitable status has never been more real.

On Jan. 6, Parliament’s Standing Committee on Finance recommended numerous changes, including Recommendation 430: “Amend the Income Tax Act to define a charity, which would remove the privileged status of ‘advancement of religion’ as a

charitable purpose, meaning faith-based organizations could lose access to tax benefits.”

The B.C. Humanist Association, a secular advocacy group, has long advocated for removing religion as a stand-alone charitable purpose. That idea is reflected in Recommendation 430. Before adopting such a proposal, the finance committee should have reviewed a study published last November by Cardus, a Canadian think tank focused on faith, civil society and public policy.

The Cardus study examined 64 Christian congregations in various provinces to assess the socio-economic value of their impact. It suggested that congregations make an $18.2-billion socioeconomic contribution to Canadian society, well in excess of tax exemptions and rebates equal to $1.7 billion. The net positive result of $16.5 billion—a “halo effect”—is more than 10

times the value of the tax exemptions.

The implications are clear: society will be worse off if the loss of religious charitable status leads to a drop of more than 10 per cent in donations to affected charities. Why risk it?

When congregations unravel, society follows in ways that go beyond mere economics. As Cardus explains, churches often provide space, often at no cost or below-market rates, for cultural and artistic events, recreation and sports, education, social services and other community activities. They also deliver addiction recovery, counselling and mental-health support, child care, refugee sponsorship and settlement services for newcomers, education and food banks.

Whether institutionally or personally, helping people is often an integral extension of religious belief. A 2012 Statistics Canada study found that the 14 per cent of Canadians who attend church weekly offer 29 per cent of the nation’s volunteer hours and provide 45 per cent of all charitable donations.

No party has explicitly endorsed removing charitable status for religion. But the Bloc Québécois, NDP and Liberals dominated the committee recommendation to remove religion as a charitable purpose. The Conservative Party, which held a minority on the committee, was alone in opposing it outright.

Randy Crosson, executive director of Freedoms Advocate, is organizing a national pushback. In a speech given Oct. 1 to the Regina Civic Awareness and Action Network, he said the recommendation was a “shot across the bow” to gauge public reaction.

“This isn’t just about donors losing tax receipts. It’s about churches losing buildings, staff losing jobs, and ministries being forced to shut down due to reduced donations. This is a direct threat to the future of faith in Canada, and it’s happening fast,” Crosson explained in an online video.

Crosson said religion enjoys less participation and more opposition than in previous decades. Church attendance has slumped since the pandemic, and some Canadians continue to criticize churches for their historical involvement in residential schools.

The Quebec government has also pursued a strongly secular approach to public policy. In 2019, Quebec’s Bill 21 used the notwithstanding clause of the Constitution to ban public servants from wearing religious symbols, such as hijabs, turbans or crucifixes. In August, Quebec’s secularism minister, Jean François Roberge, said that the “proliferation of street prayer is a serious and sensitive issue” and promised to bring legislation to ban it.

That’s why Crosson is urging religious leaders to launch a three-part campaign.

“First, an open letter drafted with legal and faith leaders to show government and the media the real value of the church in Canadian society. Second, mass signatures. We need churches, leaders and individuals to sign the letter,” Crosson says in a video appeal. “And third, a national documentary based on the open letter. This will be released publicly and spread through churches, media and social platforms.”

The Frontier Centre for Public Policy has also come out publicly against the proposed change. A report by Senior Fellow Pierre Gilbert entitled Revoking the Charitable Status for the Advancement of Religion: A Critical Assessment makes a case for the status quo, pointing to benefits such as those mentioned above.

For now, at least, the idea is on hold. A published email response by Liberal MP Karina Gould, the chair of the House of Commons’ Standing Committee on Finance, said the charitable status of faith-driven non-profits will not be revoked in the Nov. 4 budget.

That’s good news. Faith is a big motivator of charity, and it’s hard to see how a less charitable society is a better one. If governments want to balance the books, they should rein in spending, not put faith-based charities at risk.

Lee Harding is a research fellow for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

Troy Media empowers Canadian community news outlets by providing independent, insightful analysis and commentary. Our mission is to support local media in helping Canadians stay informed and engaged by delivering reliable content that strengthens community connections and deepens understanding across the country

Business

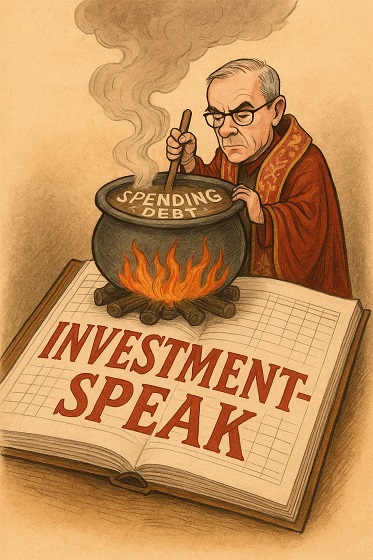

When Words Cook the Books: The Politics of ‘Investment-Speak’

The trick lies in the word “investment.” By separating “operational spending” from “capital investment,” Ottawa can now reclassify expenditures, moving them from one column to another without changing the underlying reality. A deficit remains a deficit.

Next week, Ottawa will table its first budget in nearly two years. The government has already told us what to expect. In October, the Department of Finance announced a new “Capital Budgeting Framework” that would allow Canada to “spend less so it can invest more.” The phrasing sounds prudent. It is not. It is a linguistic sleight of hand designed to obscure what the government is actually doing: spending more while pretending to exercise restraint.

The older meanings of the two words reveal the moral inversion. To spend, from the Latin dispendere, meant to weigh out and let go. It implied the careful release of what one possessed, whether money, time, or energy. In Old English and Middle English, to “spend” one’s life or strength was to pour it out, knowingly and finitely. There was gravity to the act; what was spent was gone. To invest, by contrast, came from the Latin investīre: to clothe or cover. Before it became a financial term, it referred to the ceremonial act of placing robes upon a monarch or knight, endowing them with office or honour. In its financial sense, to invest was to “clothe money” in a venture, expecting return. The first word carried finality; the second, expectancy. Spending ended a possession; investing disguised it in the promise of future gain.

From these roots, the moral difference is clear. Spending belongs to the household, measured, finite, and real. Investing belongs to the court, symbolic, ceremonial, and often self-flattering. When a government calls its spending “investment,” it does not change the transaction; it changes the costume.

The gradual adoption of this vocabulary by governments is an old habit dressed as innovation. For two decades, Ottawa has been learning to speak the language of investment as disguise. Budgets that once tabulated “program spending” now announce “investments in Canadians.” Under the Trudeau governments, tax credits and subsidies were cast as “investments in innovation.” The Canada Infrastructure Bank was sold as “leveraging private investment” rather than public debt. Even emergency COVID programs were justified as “investing in recovery.” The word became a universal solvent, dissolving distinctions between cost, borrowing, and speculation.

This year’s government has merely made the trend official. In October, the Department of Finance released Modernizing Canada’s Budgeting Approach, explaining that the new Capital Budgeting Framework would “distinguish day-to-day operational spending from capital investment.” The document asserts that this will “guide decisions and help prioritize. The trick lies in the word “investment.” By separating “operational spending” from “capital investment,” Ottawa can now reclassify expenditures, moving them from one column to another without changing the underlying reality. A deficit remains a deficit. Borrowed money is still borrowed. But call it investment, and suddenly it carries the glow of foresight and responsibility. The government plans to balance its operating budget while continuing to borrow for capital projects. The ledger will grow, but the language will comfort.

This is not merely bad accounting. It is a deliberate corruption of language in service of political evasion. And it reveals something deeper about how modern governments govern: not through honest argument but through the manipulation of words.

Ottawa has been perfecting this costume for two decades. Budgets that once listed “program spending” now announce “investments in Canadians.” Tax credits became “investments in innovation.” The Canada Infrastructure Bank was sold as “leveraging private investment,” not public debt. COVID emergency programs were justified as “investing in recovery.” The word became a universal solvent, dissolving the distinction between cost, borrowing, and speculation.

This year’s framework makes the habit official. The October document from Finance Canada promises that the new approach will “guide decisions and help prioritize investments that generate long-term benefits for Canadians, such as major projects, housing, clean energy, and infrastructure.” The tone is managerial and assured. The assumption goes unexamined: that one can divide the public purse into virtuous investment and wasteful spending, and that the government possesses the wisdom to know the difference.

Haultain Research is a reader-supported publication.

To receive new posts and support our work, consider becoming a donor or a paid subscriber.

The Prime Minister echoed the line in his own announcement: “Budget 2025 will set out our plan to spend less so we can invest more in Canada’s long-term growth.” Read carefully, the statement reveals its own dishonesty. To “spend less” no longer means reducing outlays. It means shifting expenditures into a different category where they escape the stigma of cost. The government intends to continue borrowing, but it will refer to that borrowing by a supposedly more respectable name.

The definition of capital investment is conveniently broad. It includes tax credits, corporate subsidies, and nearly any policy “that contributes to capital formation.” The Fraser Institute and others have warned that this expansiveness allows Ottawa to reclassify politically favored programs as investment, inflating the appearance of fiscal discipline while reducing transparency. A deficit becomes a “generational investment.” A subsidy becomes a “partnership.” Waste is rebranded as “capacity-building.” The language does the work that policy cannot.

Recent history exposes the fraud. Consider the electric vehicle battery subsidies, heralded as “historic investments” in the green economy. Tens of billions were promised. Projects have stalled, been postponed, or quietly abandoned. The so-called green slush fund, officially presented as an investment vehicle for sustainable innovation, turned out to be a network of cronyism and waste. These, too, were dressed as investments. When their failures emerged, the language remained untouched, as though incompetence and corruption could not breach the sanctity of the term.

The alchemy works because language shapes perception faster than arithmetic. “Investment” suggests prudence and reward. “Spending” suggests indulgence and loss. Citizens hear that the government is “investing in Canadians” and imagine return, not depletion. The moral weight of the word does the political work. Accountability fades behind aspiration.

There is a deeper danger here. Words like spend and cost belong to the vocabulary of limits. They remind us that government operates with other people’s money. Invest, as politicians now use it, belongs to the vocabulary of boundless promise. It implies benevolence without constraint, as though the state were a benefactor rather than a borrower. When the government claims to “invest in Canadians,” it implies ownership of the very people whose money it spends. The inversion of subject and object is telling. It reveals the paternalism at the heart of modern technocracy.

George Orwell wrote that political language “is designed to make lies sound truthful and murder respectable.” He understood that the corruption of speech precedes the corruption of thought. When a government renames its spending as investment, it is not simply misdescribing an accounting category. It is reshaping the citizen’s perception of what government may do. If all spending is investment, then any limit on it seems stingy, even immoral. The citizen becomes debtor to a future defined by the state.

The deceit is subtle. No one disputes that bridges or power grids can be sound investments. The deceit lies in the implication that all government activity now yields return, that every expense is productive, every grant visionary. By this logic, no spending is considered waste and no deficit is deemed reckless, as long as it is labelled as an investment. The language abolishes the distinction between consumption and creation, between present sacrifice and future gain. In doing so, it abolishes prudence itself.

Prudence, in the older sense, is not caution for its own sake. It is moral realism: the recognition that resources are finite and choices have costs. The new investment rhetoric invites the opposite illusion. Money, once moralized as investment, appears to carry no weight of trade-off. Ottawa can clothe profligacy in the robes of responsibility. The government that promises to “spend less and invest more” is like a man claiming to drink less whiskey by pouring it into crystal.

The cost of this linguistic vanity is not only fiscal. It corrodes public trust. Citizens sense the dissonance. Deficits widen, taxes climb, promises multiply. When language becomes a substitute for honesty, cynicism follows. A people that cannot trust its government’s words cannot trust its numbers.

The remedy is simple, though seldom easy: call things by their names. Spending is spending, whether on roads, welfare, or research. Some are wise, some are foolish. But none becomes virtuous by relabeling. The duty of government is not to invent euphemisms but to justify expenditures plainly and bear the consequences. That is what accountability means.

Roger Scruton observed that conservatism, properly understood, is “the politics of the tried and tested against the politics of experiment.” In fiscal speech, that means preferring accuracy to allure. A government confident in its stewardship would not fear plain-spoken spending. Only one uneasy with its own excess needs the comfort of investment.

Ottawa’s linguistic reform is therefore not a matter of diction. It is an attempt to alter reality through language, to convert liability into virtue by decree. The danger is that citizens, lulled by investment-speak, will cease to notice the arithmetic beneath. The numbers will grow; the language will glow. By the time the robe is lifted, the treasury will be bare.

That is not a forecast. It is a warning. When governments clothe waste in the garments of investment, they are not modernizing accounting. They are modernizing deceit.

We are grateful that you’re reading an article from Haultain Research.

For the full experience, and to help us bring you more quality research and commentary,

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoStrongest hurricane in 174 years makes landfall in Jamaica

-

MAiD2 days ago

MAiD2 days agoStudy promotes liver transplants from Canadian euthanasia victims

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoCanada has given $109 million to Communist China for ‘sustainable development’ since 2015

-

Internet1 day ago

Internet1 day agoMusk launches Grokipedia to break Wikipedia’s information monopoly

-

Opinion2 days ago

Opinion2 days agoBritish Columbians protest Trump while Eby brings their province to its knees

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoBill Gates walks away from the climate cult

-

Banks1 day ago

Banks1 day agoBank of Canada Cuts Rates to 2.25%, Warns of Structural Economic Damage

-

Alberta16 hours ago

Alberta16 hours agoNobel Prize nods to Alberta innovation in carbon capture