Indigenous

There are no Indian Residential School denialists, so why criminalize them?

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

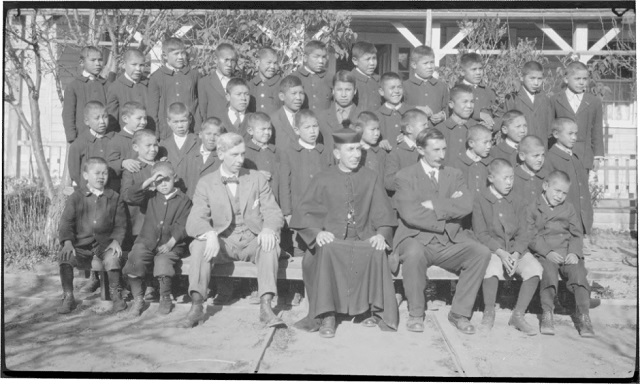

By Rodney A. Clifton, professor emeritus at the University of Manitoba and a senior fellow at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy. (He was a former Senior Boys’ Supervisor in Stringer Hall, the Anglican residence in Inuvik.)

” both sides agree that Indian Residential Schools existed, and that some children were harmed. But they disagree on the evidence needed to prove whether children were murdered and buried unceremoniously in residential schoolyards. “

In a recent Canadian Press story, Kimberly Murray, the government’s special interlocutor on unmarked graves of missing Indigenous children from residential schools, is reported as saying: “We could … make it an offense to incite hate and promote hate against Indigenous people by … denying that residential (schools) happened or downplaying what happened in the institutions.” Not surprisingly, the Liberal government of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is sympathetic to the special interlocutor’s call to action.

Ms. Murray says that Indigenous leaders across the country support her call for legislation. The Assembly of Manitoba Chiefs (AMC), for example, asked the Justice Minister, Arif Virani, to amend the criminal code to criminalize denialism. AMC Grand Chief Cathy Merrick said that enacting such a law would provide “an opportunity for Canada to demonstrate an honest commitment to reconciliation…. to deny the existence of these institutions is a form of violence.”

The focus on missing and murdered Indigenous children at residential schools became a national disgrace at the end of May 2021 when the Kamloops First Nation announced that stories from Knowledge Keepers and evidence from ground-penetrating radar (GPR) had “discovered” the graves of 215 children in the schoolyard of the Kamloops Indian Residential School.

Since that announcement, first nations across the country have discovered many more “graves,” also relying on Knowledge Keepers stories and GPR evidence. But so far, no bodies of IRS students have been exhumed from the schoolyards, even though the Chief TRC Commissioner, Justice Murry Sinclair, told CBC Radio host Matt Galloway a couple of years ago that as many as 15,000 to 25,000 Indian Residential School students are missing.

Surprisingly, these claims are not included in the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) Report. In fact, only one story of a murdered child is reported in the TRC Report, and it is the unverified story told by Doris Young about seeing a child’s murder at the Anglican Elkhorn Indian Residential School in Manitoba. The Commission reported this alleged murder but did not investigate the claim. Indeed, the Commission spent $60 million over six years and did not report any evidence, other than the Doris Young’s claim, of the murder of Indigenous children at residential schools.

What does this mean for criminalizing denialism?

There are at least three problems with potential legislation to criminalize denialism. First, Canada already has legislation on hate speech, and so new legislation is unnecessary.

Second, the definition of “denialism,” as reported above, is so vague that it would be almost impossible to convict anyone.

Finally, and most importantly, from what can be gathered from both Ms. Murray’s interim report and recent news items, practically no Canadians deny that Indian Residential Schools existed or that some children were harmed at those schools.

What Canadians seem to disagree on is the evidence that is needed to prove that IRS students were murdered, and their bodies were unceremoniously buried in unmarked graves in residential schoolyards.

On Ms. Murray’s side, supporters’ reason that “hear-say” evidence from Indigenous Knowledge Keepers and shadows on GPR screens are adequate to prove the claim. On the other side, the so-called “deniers” reason that forensic evidence from exhumed bodies is needed.

So, both sides agree that Indian Residential Schools existed, and that some children were harmed. But they disagree on the evidence needed to prove whether children were murdered and buried unceremoniously in residential schoolyards.

The Canadian law enforcement and justice system is the proper agency for an impartial investigation of this claim, and if evidence is obtained, to criminally charge those Indigenous and non-Indigenous IRS employees responsible and to report their names and crimes if they are deceased.

Surely Canadians would support such an impartial investigation leading to possible criminal charges. Till that happens, there is no reason to demonize the so-called “deniers” by those who disagree with the evidence they think is necessary to answer this important question. Without an independent investigation along with a public report, Canada cannot reach a fair and just reconciliation between Indigenous and non-Indigenous Canadians.

Indeed, many people are wondering why such a rigorous, systematic, investigation has not yet been conducted. It is the time to settle this issue so that both sides—indeed all Canadians—can move on from being pitted against each other over an issue that can be easily resolved with an independent investigation by competent justice officials.

Rodney A. Clifton is a is a professor emeritus at the University of Manitoba and a senior fellow at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy. He lived for four months in Old Sun, the Anglican Residential School on the Blackfoot (Siksika) First Nation, and was the Senior Boys’ Supervisor in Stringer Hall, the Anglican residence in Inuvik. Rodney Clifton and Mard DeWolf are the editors of From Truth Comes Reconciliation: An Assessment of the Truth and Reconciliation Commission Report (Frontier Centre for Public Policy, 2021). A second and expanded edition of this book will be published in 2024.

Indigenous

Internal emails show Canadian gov’t doubted ‘mass graves’ narrative but went along with it

From LifeSiteNews

Parks Canada employees admitted that ground-penetrating radar results were likely false positives.

Internal emails have revealed that federal workers questioned the residential school narrative as early as 2023, despite gaslighting Canadians who questioned media’s claims.

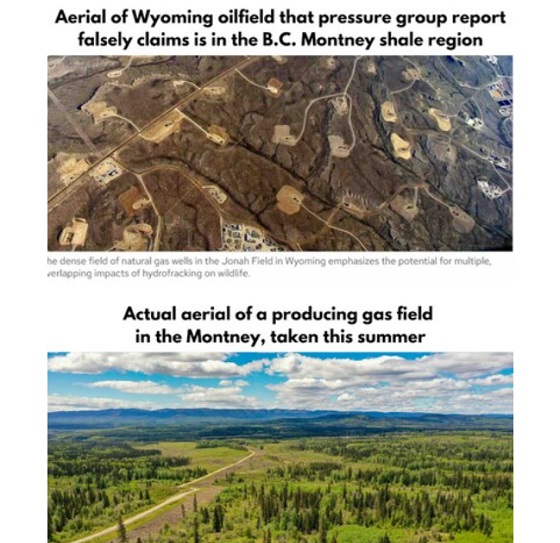

According to confidential staff emails published by Blacklock’s Reporter on July 4, Parks Canada, the government agency which manages national parks, admitted that claims of hundreds of graves found at an Indian Residential School in Kamloops, British Columbia were unfounded and likely false.

“Authors refer to the 215 ground-penetrating radar hits that were reported in 2021 as ‘graves’ or ‘burials,’” wrote one Parks Canada consultant. “But none of these sites have been investigated further to determine that they are graves.

Like most Canadians, Parks Canada staff initially believed the alleged discovery of 215 so-called “unmarked” graves in Kamloops during the summer of 2021. The story alleged that hundreds of Indigenous children were killed and secretly buried at the residential school.

READ: Canadian councilor punished for denying unproven ‘mass graves’ narrative seeks court review

Canada’s Residential School system was a structure of boarding schools funded by the Canadian government and run by both the Catholic Church and other churches that ran from the late 19th century until the last school closed in 1996.

While some children did tragically die at the once-mandatory boarding schools, evidence has revealed that many of the children passed away as a result of unsanitary conditions due to underfunding by the federal government, not the Catholic Church.

In 2021, Parks Canada hired historians “to help identify any gaps or errors” in the claim of finding 215 unmarked graves before designating the Kamloops Indian Residential School as a historic site.

However, according to their internal emails, Parks Canada discovered that the technology used to discover the “graves” is often misleading and cannot be relied upon.

“Ground-penetrating radar often throws up false positives, anomalies that are not indicative of anything significant,” a consultant wrote. “I suggest that until there is further investigation of the sites at Kamloops the report refer to them as ‘possible graves’ or ‘probable graves’ or ‘likely graves’ rather than ‘graves.’”

As a result, Parks Canada changed their report to list the anomalies as “probable unmarked graves” rather than “unmarked graves.”

“The challenge is that ground-penetrating radar does not provide evidence of potential unmarked graves,” said the staff email. “It provides evidence of anomalies. I am quoting the archaeologists here.”

“Regarding the topic of ground-penetrating radar, I’ve made a suggested revision,” wrote another manager. “It might be preferable to not use the term ‘anomalies’ for now.” Staff were also advised to “stay extra quiet” on the designation of the Residential School as a national historic site.

To date, there have been no mass graves discovered at residential schools. However, following claims blaming the deaths on the Catholic clergy who ran the schools, over 100 churches have been burned or vandalized across Canada in seeming retribution.

READ: Despite claims of 215 ‘unmarked graves,’ no bodies have been found at Canadian residential school

Despite their conclusions, Parks Canada refused to publicly contradict the residential school narrative. On their website discussing the schools, the government agency does not mention the unmarked graves and also fails to debunk the claims of mass unmarked graves.

Furthermore, while the agency internally questioned and doubted the validity of the claims, Canadians who publicly opposed the mainstream narrative were condemned as denialists and often punished.

Despite the lack of physical evidence, in 2022, Canada’s House of Commons under Liberal Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, formalized the controversy and declared the residential school program to be considered a historic act of “genocide.”

Business

Ottawa has spent nearly $18 billion settling Indigenous ‘specific claims’ since 2015

From the Fraser Institute

By Tom Flanagan

Since 2015, the federal government has paid nearly $18 billion settling an increasing number of ‘specific claims’ by First Nations, including more than $7 billion last year alone, finds a new study released today by the Fraser Institute, an independent, non-partisan Canadian public policy think tank.

“Specific claims are for past treaty breaches, and as such, their number should be finite. But instead of declining over time, the number of claims keeps growing as lucrative settlements are reached, which in turn prompts even more claims,” said Tom Flanagan, Fraser Institute senior fellow, professor emeritus of political science at the University of Calgary and author of Specific Claims—an Out-of-Control Program.

The study reveals details about “specific claims,” which began in 1974 and are filed by First Nations who claim that Canadian governments—past or present—violated the Indian Act or historic treaty agreements, such as when governments purchased reserve land for railway lines or hydro projects. Most “specific claims” date back 100 years or more. Specific claims are contrasted with comprehensive claims, which arise from the absence of a treaty.

Crucially, the number of specific claims and the value of the settlement paid out have increased dramatically since 2015.

In 2015/16, 11 ‘specific claims’ were filed with the federal government, and the total value of the settlements was $27 million (in 2024 dollars, to adjust for inflation). The number of claims increased virtually every year since so that by 2024/25, 69 ‘specific claims’ were filed, and the value of the settlements in 2024/25 was $7.061 billion. All told, from 2015/16 to 2024/25, the value of all ‘specific claims’ settlements was $17.9 billion (inflation adjusted).

“First Nations have had 50 years to study their history, looking for violations of treaty and legislation. That is more than enough time for the discovery of legitimate grievances,” Flanagan said.

“Ottawa should set a deadline for filing specific claims so that the government and First Nations leaders can focus instead on programs that would do more to improve the living standards and prosperity for both current and future Indigenous peoples.”

Specific Claims: An Out-of-Control Program

- Specific claims are based on the government’s alleged failure to abide by provisions of the Indian Act or a treaty.

- The federal government began to entertain such claims in 1974. The number and value of claims increased gradually until 2017, when both started to rise at an extraordinary rate.

- In fiscal year 2024/25, the government settled 69 claims for an astonishing total of $7.1 billion dollars.

- The evidence suggests at least two causes for this sudden acceleration. One was the new approach of Justin Trudeau’s Liberal government toward settling Indigenous claims, an approach adopted in 2015 and formalized by Minister of Justice Jodi Wilson-Raybould’s 2019 practice directive. Under the new policy, the Department of Justice was instructed to negotiate rather than litigate claims.

- Another factor was the recognition, beginning around 2017, of “cows and plows” claims based on the allegation that agricultural assistance promised in early treaties—seed grain, cattle, agricultural implements—never arrived or was of poor quality.

- The specific-claims process should be terminated. Fifty years is long enough to discover legitimate grievances.

- The government should announce a short but reasonable period, say three years, for new claims to be submitted. Claims that have already been submitted should be processed, but with more rigorous instructions to the Department of Justice for legal scrutiny.

- The government should also require more transparency about what happens to these settlements. At present, much of the revenue paid out disappears into First Nations’ “settlement trusts”, for which there is no public disclosure.

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoCOWBOY UP! Pierre Poilievre Promises to Fight for Oil and Gas, a Stronger Military and the Interests of Western Canada

-

MAiD1 day ago

MAiD1 day agoCanada’s euthanasia regime is already killing the disabled. It’s about to get worse

-

Crime2 days ago

Crime2 days agoEyebrows Raise as Karoline Leavitt Answers Tough Questions About Epstein

-

Alberta2 days ago

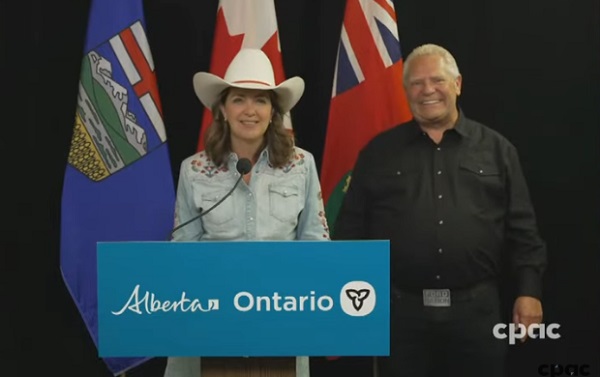

Alberta2 days agoAlberta and Ontario sign agreements to drive oil and gas pipelines, energy corridors, and repeal investment blocking federal policies

-

Fraser Institute1 day ago

Fraser Institute1 day agoBefore Trudeau average annual immigration was 617,800. Under Trudeau number skyrocketted to 1.4 million from 2016 to 2024

-

Censorship Industrial Complex14 hours ago

Censorship Industrial Complex14 hours agoCanadian pro-freedom group sounds alarm over Liberal plans to revive internet censorship bill

-

Daily Caller2 days ago

Daily Caller2 days ago‘I Know How These People Operate’: Fmr CIA Officer Calls BS On FBI’s New Epstein Intel

-

International2 days ago

International2 days agoChicago suburb purchases childhood home of Pope Leo XIV