Frontier Centre for Public Policy

Is the Price of Reconciliation that we Must Pretend to Believe a Lie?

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

Even the Kamloops band is backing away from its most extreme claim, that ‘bodies were found’

The price we are being told that we must pay to achieve “reconciliation” is becoming clear. We must pretend to believe a lie.

The lie is that 215, and then thousands, of indigenous students of residential schools were “disappeared” while at the schools — that they died under sinister circumstances while under the care of the priests, nuns and teachers running the schools, and were buried in secrecy.

To top it off, it is claimed that fellow students — “as young as six” — were forced by these evil priests to dig the graves. The fact that there is not one scintilla of good evidence to support this deeply anti-Catholic blood libel is not supposed to deter us from accepting it as fact. We are being told that we must pretend to believe this lie if we want to achieve “reconciliation”.

If there was any doubt that the Assembly of First Nations (AFN) was insisting that Canadians must pretend to believe the false claim, it was dispelled when they angrily rejected the funding cap that the federal government had placed on its ill-considered promise to provide a total of $320 million to indigenous communities that chose to go on their own “missing children/unmarked graves” search.

The chiefs showed who was boss, and the federal government meekly submitted, and cancelled the funding cap.

The government coffers were left wide open, and indigenous communities expanded existing searches for “missing children.” In reality these children were never missing. As Tom Flanagan explains in Grave Error (above), they were “forgotten children” who had been properly buried in marked graves that were subsequently left untended and forgotten by their families.

Be that as it may, as a result of AFN activism, and government and media incompetence, the Kamloops claim morphed into an officially sanctioned lie.

But where is the truth in all of this?

Most of us knew, even when this claim was first made in 2021, that these grisly tales of sinister deaths and secret burials could not possibly be true.

There is simply no historical record of any such thing occurring.

There are no records of parents frantically looking for children who suddenly went missing from residential schools, no police reports of missing children. Nothing.

In fact the extensive records we do have say exactly the opposite — namely that the deaths of children who sadly died of the diseases of the day at residential schools were all properly recorded, and that almost all of the deceased children were buried by their parents on their home reserves.

The small minority who were buried in special school cemeteries, (because the transportation of the bodies back to remote reserves was impractical,) all received Christian burials. Their places of burial were made known to their parents. The fact is that record keeping of indigenous children at residential schools was far superior to record keeping of the children on reserves, where far greater numbers died of exactly the same diseases.

But for reasons best left to future historians to ponder the Trudeau government and its CBC media ally immediately accepted the crackpot Kamloops claim as true. CBC and other gullible media went into overdrive pumping out misinformation in support of the baseless claim, while the Trudeau government ordered all flags on federal buildings across Canada lowered, where they remained for six months!

Trudeau’s indigenous affairs minister, Marc Miller — perhaps the worst Indian Affairs minister in the history of this country — recklessly promised $320 million to indigenous communities that wanted to make similar claims. And, of course, others did almost immediately.

Down the road, Chief Willie Sellars, of the Williams Lake indigenous community, outdid the rhetoric of his colleague, Chief Casimir. According to Sellars, priests had not only killed countless indigenous children, but had thrown their bodies into “rivers, streams and lakes” as well as the usual old standards of throwing bodies into school furnaces and incinerators. Other communities wanting in on the money jumped onto the bandwagon with increasingly fantastical tales.

The result of this Trudeau government recklessness — aided by a gullible media that asked no questions — was predictable. These false stories became etched in stone as the truth within the indigenous community. A victim mentality that was already deeply imbedded became pathological, as indigenous communities became convinced — on evidence that was entirely false — that they were victims of a genocide committed by their neighbours.

The chiefs also silenced the many thoughtful members within their communities who knew that these stories of murderous priests were not true. As investigative reporter, Terry Glavin, explains, even among the Tk’emlups community there were always sensible voices who did not believe those claims:

“From the outset, even among Tk’emlúps people there was a great deal of skepticism and disbelief in stories about nuns waking children in the middle of the night to bury their murdered classmates under the light of the moon”

But instead of heeding those sensible indigenous voices, and even as it became increasingly clear to Canadians that these stories were just tall tales, there was so much money in it that the chiefs doubled down. They insisted that Canadians must pretend to believe that the claims were true.

That would be their price for “reconciliation”.

As noted above, the weak Liberal government gave into this blackmail by removing the funding cap on searches it had tried to impose. But other important institutions cravenly played along with what was now an officially sanctioned lie as well.

Jon Kay explains in his recent Quillette essay how the Law Society of British Columbia is now insisting that anyone who wants to be a lawyer in that province must pretend to believe the “evil priest” line of stories.

Other law schools and law societies across Canada are doing this as well. They are so focused on what they perceive as the holy grail of “reconciliation” that they are prepared to sacrifice a pursuit of truth as their goal, and force their own students — our future lawyers and judges — to do the same.

Our public schools — to bring about “reconciliation — are indoctrinating our children with lessons about the “215 Kamloops graves” and other misinformation, such as the “Charlie Wenjack” story.

Children are taught that Wenjack was abused by Catholic priests and nuns in his residential school, and ran away as a result.

In fact, as author and historian Robert MacBain explains in his important book, “The Lonely Death Of An Ojibway Boy” Charlie Wenjack lived at a Protestant hostel run by a kindly indigenous family, attended school by the day in Kenora, and probably never saw a residential school, or met a priest or nun, in his life.

But, in the interests of “reconciliation” our children are being misinformed by their teachers.

And when a teacher does dare to tell the truth, as when B.C. teacher, Jim McMurtry told his students that the children who died in residential schools died of the diseases of the day — and were not tortured to death, as was being reported — he was frogmarched from his classroom, and summarily fired.

Or Frances Widdowson, who was fired from her tenured university position largely for daring to dispute what was becoming an increasingly extreme residential school narrative.

All of this obvious unfairness, is happening in the name of “reconciliation.” The senior lawyers who oversee the Law Society, and the educators who select our children’s school curricula are doing a great disservice to this country. As are our MPs who foolishly labelled Canada as genocidal, based on the same false Kamloops claim.

As are our senior indigenous leaders, who know by know that the murderous, secret-burying priest story has always been just a silly ghost story that children tell to scare one another. Yet they insist that Canadians must pretend to believe it, or they will withhold the “reconciliation” that they wield like a sledge hammer over our heads.

It should have occurred to everyone by now that if the price of “reconciliation” is pretending to believe a lie, the price is far too high. That kind of “reconciliation” is worth nothing.

In actual fact, what this country and its indigenous population needs is not “reconciliation” at all. Too many indigenous people are stuck at the bottom of the socioeconomic ladder. What they need is not “reconciliation” but integration into the economy, and the opportunity to participate in it. As for the opportunists who exploit a false claim to benefit themselves, they deserve only our contempt.

What nobody needs is a country where citizens must lie to each other in order to stay together.

And now, to add insult to injury, MP Leah Gazan wants to make it a law that we must all lie to each other by criminalizing what she calls “residential school denialism”. She specifically singles out the Kamloops claim as something Canadians must accept as true. As she sees it any Canadian who refuses to do so, or who dares to suggest that the positives, as well as the negatives of residential schooling should be recognized, should be made a criminal. Dostoevsky famously asked if there will come a time “when intelligent people will be banned from thinking, so as not to offend the imbeciles”. Has that time arrived?

Brian Giesbrecht, retired judge, is a Senior Fellow at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

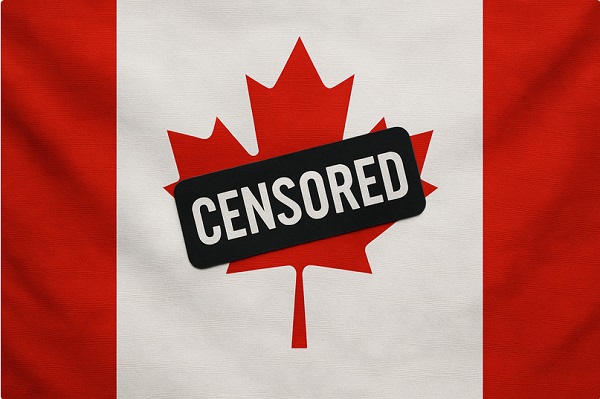

Censorship Industrial Complex

Ottawa’s New Hate Law Goes Too Far

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

By Lee Harding

Ottawa says Bill C-9 fights hate. Critics say it turns ordinary disagreement into a potential crime.

Discriminatory hate is not a good thing. Neither, however, is the latest bill by the federal Liberal government meant to fight it. Civil liberties organizations and conservative commentators warn that Bill C-9 could do more to chill legitimate speech than curb actual hate.

Bill C-9 creates a new offence allowing up to life imprisonment for acts motivated by hatred against identifiable groups. It also creates new crimes for intimidation or obstruction near places of worship or community buildings used by identifiable groups. The bill adds a new hate propaganda offence for displaying terrorism or hate symbols.

The Canadian Civil Liberties Association (CCLA) warns the legislation “risks criminalizing some forms of protected speech and peaceful protest—two cornerstones of a free and democratic society—around tens of thousands of community gathering spaces in Canada.” The CCLA sees no need to add to existing hate laws.

Bill C-9 also removes the requirement that the Attorney General consent to lay charges for existing hate propaganda offences. The Canadian Constitution Foundation (CCF) calls this a major flaw, noting it removes “an important safeguard for freedom of expression that has been part of Canada’s law for decades.” Without that safeguard, decisions to prosecute may depend more on local political pressures and less on consistent national standards.

Strange as it sounds, hatred just will not be what it used to be if this legislation passes. The core problem begins with how the bill redefines the term itself.

Previously, the Supreme Court of Canada said hatred requires “extreme manifestations” of detestation or vilification that involve destruction, abhorrence or portraying groups as subhuman or innately evil. Instead, Bill C-9 defines hatred as “detestation or vilification,” stronger than “disdain or dislike.” That is a notably lower threshold. This shift means that ordinary political disagreement or sharp criticism could now be treated as criminal hatred, putting a wide range of protected expression at real risk.

The bill also punishes a hateful motivation more than the underlying crime. For example, if a criminal conviction prompted a sentence of two years to less than five years, a hateful motivation would add as much as an additional five years of jail time.

On paper, most Canadians may assume they will never be affected by these offences. In practice, the definition of “hate” is already stretched far beyond genuine threats or violence.

Two years ago, the 1 Million March for Children took place across Canada to protest the teaching of transgender concepts to schoolchildren, especially the very young. Although such opposition is a valid position, unions, LGBT advocates and even Newfoundland and Labrador Conservatives adopted the “No Space For Hate” slogan in response to the march. That label now gets applied far beyond real extremism.

Public pressure also shapes how police respond to protests. If citizens with traditional values protest a drag queen story hour near a public library, attendees may demand that police lay charges and accuse officers of implicit hatred if they refuse. The practical result is clear: officers may feel institutional pressure to lay charges to avoid being accused of bias, regardless of whether any genuine threat or harm occurred.

Police, some of whom take part in Pride week or work in stations decorated with rainbow colours in June, may be wary of appearing insensitive or intolerant. There have also been cases where residents involved in home invasion incidents were charged, and courts later determined whether excessive force was used. In a similar way, officers may lay charges first and allow the courts to sort out whether a protest crossed a line. Identity-related considerations are included in many workplace “sensitivity training” programs, and these broader cultural trends may influence how such situations are viewed. In practice, this could mean that protests viewed as ideologically unfashionable face a higher risk of criminal sanction than those aligned with current political priorities.

If a demonstrator is charged and convicted for hate, the Liberal government could present the prosecution as a matter for the justice system rather than political discretion. It may say, “It was never our choice to charge or convict these people. The system is doing its job. We must fight hate everywhere.”

Provincial governments that support prosecution will be shielded by the inability to show discretion, while those that would prefer to let matters drop will be unable to intervene. Either way, the bill could increase tensions between Ottawa and the provinces. This could effectively centralize political authority over hate-related prosecutions in Ottawa, regardless of regional differences in values or enforcement priorities.

The bill also raises concerns about how symbols are interpreted. While most Canadians would associate the term “hate symbol” with a swastika, some have linked Canada’s former flag to extremism. The Canadian Anti-Hate Network did so in 2022 in an educational resource entitled “Confronting and preventing hate in Canadian schools.”

The flag, last used nationally in 1965, was listed under “hate-promoting symbols” for its alleged use by the “alt-right/Canada First movement” to recall when Canada was predominantly white. “Its usage in modern times is an indicator of hate-promoting beliefs,” the resource insisted. If a historic Canadian symbol can be reclassified this easily, it shows how subjective and unstable the definition of a “hate symbol” could become under this bill.

These trends suggest the legislation jeopardizes not only symbols associated with Canada’s past, but also the values that supported open debate and free expression. Taken together, these changes do not merely target hateful behaviour. They create a legal framework that can be stretched to police dissent and suppress unpopular viewpoints. Rest in peace, free speech.

Lee Harding is a research fellow for the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

Business

Canada Can Finally Profit From LNG If Ottawa Stops Dragging Its Feet

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

By Ian Madsen

Canada’s growing LNG exports are opening global markets and reducing dependence on U.S. prices, if Ottawa allows the pipelines and export facilities needed to reach those markets

Canada’s LNG advantage is clear, but federal bottlenecks still risk turning a rare opening into another missed opportunity

Canada is finally in a position to profit from global LNG demand. But that opportunity will slip away unless Ottawa supports the pipelines and export capacity needed to reach those markets.

Most major LNG and pipeline projects still need federal impact assessments and approvals, which means Ottawa can delay or block them even when provincial and Indigenous governments are onside. Several major projects are already moving ahead, which makes Ottawa’s role even more important.

The Ksi Lisims floating liquefaction and export facility near Prince Rupert, British Columbia, along with the LNG Canada terminal at Kitimat, B.C., Cedar LNG and a likely expansion of LNG Canada, are all increasing Canada’s export capacity. For the first time, Canada will be able to sell natural gas to overseas buyers instead of relying solely on the U.S. market and its lower prices.

These projects give the northeast B.C. and northwest Alberta Montney region a long-needed outlet for its natural gas. Horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing made it possible to tap these reserves at scale. Until 2025, producers had no choice but to sell into the saturated U.S. market at whatever price American buyers offered. Gaining access to world markets marks one of the most significant changes for an industry long tied to U.S. pricing.

According to an International Gas Union report, “Global liquefied natural gas (LNG) trade grew by 2.4 per cent in 2024 to 411.24 million tonnes, connecting 22 exporting markets with 48 importing markets.” LNG still represents a small share of global natural gas production, but it opens the door to buyers willing to pay more than U.S. markets.

LNG Canada is expected to export a meaningful share of Canada’s natural gas when fully operational. Statistics Canada reports that Canada already contributes to global LNG exports, and that contribution is poised to rise as new facilities come online.

Higher returns have encouraged more development in the Montney region, which produces more than half of Canada’s natural gas. A growing share now goes directly to LNG Canada.

Canadian LNG projects have lower estimated break-even costs than several U.S. or Mexican facilities. That gives Canada a cost advantage in Asia, where LNG demand continues to grow.

Asian LNG prices are higher because major buyers such as Japan and South Korea lack domestic natural gas and rely heavily on imports tied to global price benchmarks. In June 2025, LNG in East Asia sold well above Canadian break-even levels. This price difference, combined with Canada’s competitive costs, gives exporters strong margins compared with sales into North American markets.

The International Energy Agency expects global LNG exports to rise significantly by 2030 as Europe replaces Russian pipeline gas and Asian economies increase their LNG use. Canada is entering the global market at the right time, which strengthens the case for expanding LNG capacity.

As Canadian and U.S. LNG exports grow, North American supply will tighten and local prices will rise. Higher domestic prices will raise revenues and shrink the discount that drains billions from Canada’s economy.

Canada loses more than $20 billion a year because of an estimated $20-per-barrel discount on oil and about $2 per gigajoule on natural gas, according to the Frontier Centre for Public Policy’s energy discount tracker. Those losses appear directly in public budgets. Higher natural gas revenues help fund provincial services, health care, infrastructure and Indigenous revenue-sharing agreements that rely on resource income.

Canada is already seeing early gains from selling more natural gas into global markets. Government support for more pipelines and LNG export capacity would build on those gains and lift GDP and incomes. Ottawa’s job is straightforward. Let the industry reach the markets willing to pay.

Ian Madsen is a senior policy analyst at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy.

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoTanker ban politics leading to a reckoning for B.C.

-

Energy2 days ago

Energy2 days agoMeet REEF — the massive new export engine Canadians have never heard of

-

Energy18 hours ago

Energy18 hours agoCanada’s future prosperity runs through the northwest coast

-

Fraser Institute2 days ago

Fraser Institute2 days agoClaims about ‘unmarked graves’ don’t withstand scrutiny

-

Alberta2 days ago

Alberta2 days agoHere’s why city hall should save ‘blanket rezoning’ in Calgary

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoToo nice to fight, Canada’s vulnerability in the age of authoritarian coercion

-

Fly Straight - John Ivison1 day ago

Fly Straight - John Ivison1 day agoMPs who cross the floor are dishonourable members

-

Business2 days ago

Business2 days agoUNDRIP now guides all B.C. laws. BC Courts set off an avalanche of investment risk