Community

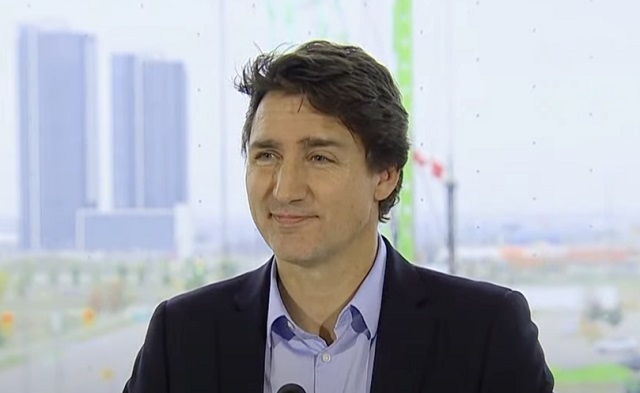

Planned Obsolescence: Trucks and Politicians

When I last negotiated the purchase of a new truck, the sales person gushed over having “the industry’s best” warranty. Months after the purchase, when I queried about whether a repair would be covered under warranty, the same person told me, “no, you only have “ this warranty.

When, during various elections, I was pondering on candidates to vote for I was given promises after promises. As after every election the back pedaling began. Usually it starts, with new governments, we did not know how bad the books were, so we have to postpone promised spending.

The sales pitches work, I bought the truck, the political promises worked, the new governments were elected, but we still did not gain our money’s or our trust’s worth. We were all seduced by different parts of the sales pitches and different promises and more often than not we were let down.

I did not ask the sales person whether the warranty would cover each and every scenario and part, and I did not read or comprehend fully all the exemptions and conditions of the warranty, and I did not apply all the scenarios and excuses to every political promise made during the elections. I finally just rolled the dice on my purchase and vote, and hoped for the best.

I knew in a few years I would be trading in my truck and my politicians, so I felt the risk was worth it. The test would be whether I stay with the same brand or political party or candidate. There are those who do stay with the same brand, political party and candidate, blindly, it sometimes seem, but I do not. They have to earn my money and/or vote.

Being an optimist, I hope that my new truck or politician will be worthy of my investment or support, and I hope they do not fail me when I need them the most. My livelihood depends on them. Different ways, no doubt, but they do affect my and my family’s lives.

Planned obsolescence or built-in obsolescence in industrial design and economics is a policy of planning or designing a product with an artificially limited useful life, so it will become obsolete (that is, unfashionable or no longer functional) after a certain period of time.(according to wikipedia)

This is important, because I knew my truck will be obsolete in a few years or in a few hundred thousand kilometres and my politicians will be obsolete in a few terms so I keep these in mind during negotiating and voting.

Things may change. I may trade in my lemon of a truck early or I may keep old reliable longer, that depends on the truck. Politicians can be assured of a multi-year term before the next vote and different levels have different terms of “Planned Obsolescence”.

Federal governments usually get changed every ten years or 2 terms, and I think that still holds true. Provincially, governments seem to stay for rather long extended periods, but there is serious debate that the current Alberta provincial government may be the anomaly and have a 4 year expiration date. Time will tell.

Municipally, councillors and mayors have the longest periods of planned obsolescence, due mainly to familiarity and voting practices. Often times considered the least important in the political hierarchy, they can have the greatest effect on our daily lives.

Many believe that the councillors and mayors are merely figureheads and rubber stamps with little influence, and there is some basis for that. Thus the adage that you cannot fight city hall. Name recognition wins a seat, and multiple terms are a given, so promises are ignored and forgotten, which is disappointing. There is always hope.

Times change, and our needs change. The truck I bought 3 years ago may not be suitable today, as do our politicians. Perhaps today’s candidates need to be more assertive or aggressive, perhaps the good ol’incumbant may not be the best choice, in today’s economy or political environment. The status quo, or the establishment, may not cut it anymore?

Donald Trump, the gaffe-prone, outspoken, republican U.S. presidential candidate, may not become president, but he is a warning to all political parties and candidates, that people are looking for more than what has normally been offered.

Imports are increasingly supplanting domestic trucks in the market place. The NDP surprised the provincial backrooms, the nation rallied around the third party, Liberals, and municipally there are stirrings of unrest.

In a few weeks, the U.S. election will be over and I hope they study and learn from the rise and impact of the anti-establishment vote. Here in Alberta we will spend the next year listening to incumbents who will suddenly find it necessary to voice their concerns and opinions, promises and issues may be addressed, and perhaps see an emergence of an anti-establishment constituency.

I will probably buy my next truck from a different salesman.

Thank you.

Community

SPARC Red Deer – Caring Adult Nominations open now!

Red Deer community let’s give a round of applause to the incredible adults shaping the future of our kids. Whether they’re a coach, neighbour, teacher, mentor, instructor, or someone special, we want to know about them!

Tell us the inspiring story of how your nominee is helping kids grow up great. We will honour the first 100 local nominees for their outstanding contributions to youth development. It’s time to highlight those who consistently go above and beyond!

To nominate, visit Events (sparcreddeer.ca)

Addictions

‘Harm Reduction’ is killing B.C.’s addicts. There’s got to be a better way

From the Frontier Centre for Public Policy

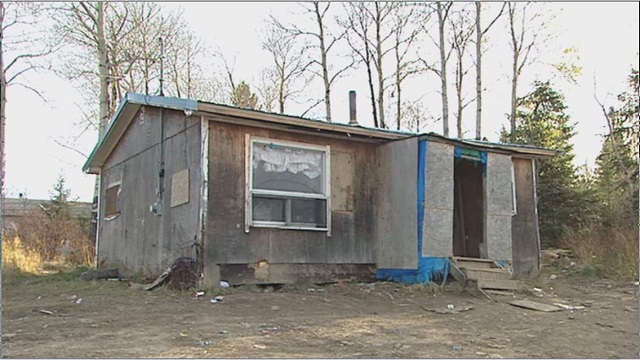

B.C. recently decriminalized the possession of small amounts of illicit drugs. The resulting explosion of addicts using drugs in public spaces, including parks and playgrounds, recently led the province’s NDP government to attempt to backtrack on this policy

Fuelled by the deadly manufactured opioid fentanyl, Canada’s national drug overdose rate stood at 19.3 people per 100,000 in 2022, a shockingly high number when compared to the European Union’s rate of just 1.8. But national statistics hide considerable geographic variation. British Columbia and Alberta together account for only a quarter of Canada’s population yet nearly half of all opioid deaths. B.C.’s 2022 death rate of 45.2/100,000 is more than double the national average, with Alberta close behind at 33.3/100,00.

In response to the drug crisis, Canada’s two western-most provinces have taken markedly divergent approaches, and in doing so have created a natural experiment with national implications.

B.C. has emphasized harm reduction, which seeks to eliminate the damaging effects of illicit drugs without actually removing them from the equation. The strategy focuses on creating access to clean drugs and includes such measures as “safe” injection sites, needle exchange programs, crack-pipe giveaways and even drug-dispensing vending machines. The approach goes so far as to distribute drugs like heroin and cocaine free of charge in the hope addicts will no longer be tempted by potentially tainted street drugs and may eventually seek help.

But safe-supply policies create many unexpected consequences. A National Post investigation found, for example, that government-supplied hydromorphone pills handed out to addicts in Vancouver are often re-sold on the street to other addicts. The sellers then use the money to purchase a street drug that provides a better high — namely, fentanyl.

Doubling down on safe supply, B.C. recently decriminalized the possession of small amounts of illicit drugs. The resulting explosion of addicts using drugs in public spaces, including parks and playgrounds, recently led the province’s NDP government to attempt to backtrack on this policy — though for now that effort has been stymied by the courts.

According to Vancouver city councillor Brian Montague, “The stats tell us that harm reduction isn’t working.” In an interview, he calls decriminalization “a disaster” and proposes a policy shift that recognizes the connection between mental illness and addiction. The province, he says, needs “massive numbers of beds in treatment facilities that deal with both addictions and long-term mental health problems (plus) access to free counselling and housing.”

In fact, Montague’s wish is coming true — one province east, in Alberta. Since the United Conservative Party was elected in 2019, Alberta has been transforming its drug addiction policy away from harm reduction and towards publicly-funded treatment and recovery efforts.

Instead of offering safe-injection sites and free drugs, Alberta is building a network of 10 therapeutic communities across the province where patients can stay for up to a year, receiving therapy and medical treatment and developing skills that will enable them to build a life outside the drug culture. All for free. The province’s first two new recovery centres opened last year in Lethbridge and Red Deer. There are currently over 29,000 addiction treatment spaces in the province.

This treatment-based strategy is in large part the work of Marshall Smith, current chief of staff to Alberta’s premier and a former addict himself, whose life story is a testament to the importance of treatment and recovery.

The sharply contrasting policies of B.C. and Alberta allow a comparison of what works and what doesn’t. A first, tentative report card on this natural experiment was produced last year in a study from Stanford University’s network on addiction policy (SNAP). Noting “a lack of policy innovation in B.C.,” where harm reduction has become the dominant policy approach, the report argues that in fact “Alberta is currently experiencing a reduction in key addiction-related harms.” But it concludes that “Canada overall, and B.C. in particular, is not yet showing the progress that the public and those impacted by drug addiction deserve.”

The report is admittedly an early analysis of these two contrasting approaches. Most of Alberta’s recovery homes are still under construction, and B.C.’s decriminalization policy is only a year old. And since the report was published, opioid death rates have inched higher in both provinces.

Still, the early returns do seem to favour Alberta’s approach. That should be regarded as good news. Society certainly has an obligation to try to help drug users. But that duty must involve more than offering addicts free drugs. Addicted people need treatment so they can kick their potentially deadly habit and go on to live healthy, meaningful lives. Dignity comes from a life of purpose and self-control, not a government-funded fix.

Susan Martinuk is a senior fellow at the Frontier Centre for Public Policy and author of the 2021 book Patients at Risk: Exposing Canada’s Health Care Crisis. A longer version of this article recently appeared at C2CJournal.ca.

-

COVID-192 days ago

COVID-192 days agoPro-freedom Canadian nurse gets two years probation for protesting COVID restrictions

-

espionage2 days ago

espionage2 days agoTrudeau’s office was warned that Chinese agents posed ‘existential threat’ to Canada: secret memo

-

Economy2 days ago

Economy2 days agoMassive deficits send debt interest charges soaring

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoBusiness investment key to addressing Canada’s productivity crisis

-

Jordan Peterson1 day ago

Jordan Peterson1 day agoJordan Peterson slams CBC for only interviewing pro-LGBT doctors about UK report on child ‘sex changes’

-

International1 day ago

International1 day agoBrussels NatCon conference will continue freely after court overturns police barricade

-

Business1 day ago

Business1 day agoFederal budget fails to ‘break the glass’ on Canada’s economic growth crisis

-

Frontier Centre for Public Policy1 day ago

Frontier Centre for Public Policy1 day agoThe Smallwood solution